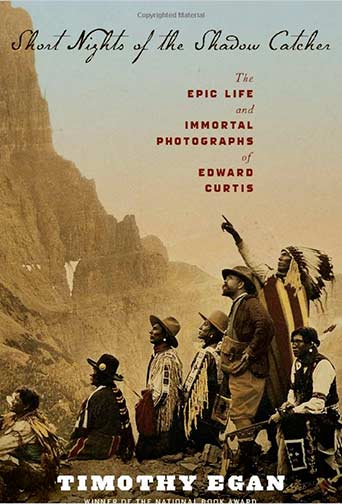

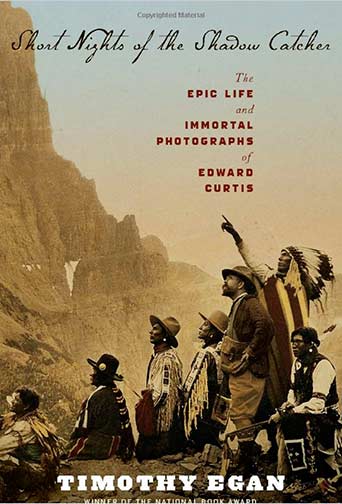

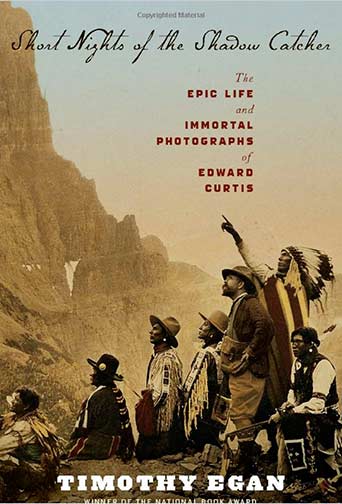

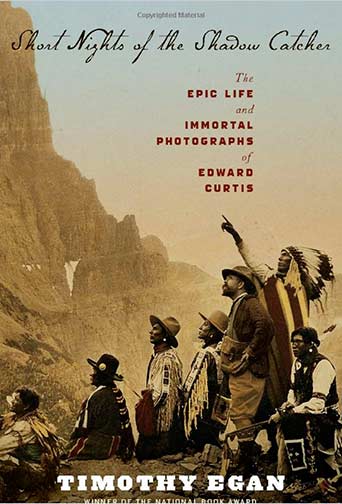

Timothy Egan’s Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, is a meticulously detailed biography of photographer Edward S. Curtis, whose early twentieth century, twenty volume North American Indians(hereafter referred to as NAI), stands as a cornerstone of photography as well as ethnography.

Although Egan has a Pulitzer as well as two National Book Awards (the latest was for this book), reading it didn’t answer many of the questions I have about the inexhaustible sources of creativity, genius and stubborn ambition that Curtis had in reserve. Nor has Egan escaped the wrath of ethnographers whose sense of ivory tower ethics seems above the fruited plain, as witnessed by the review in the Wall St. Journal. It’s the central problem that has hounded Curtis ever since volumes of NAI were first published—he paid his subjects, and often posed them in traditional dress, rather than in the shirts and pants that missionaries and government agents from the Bureau of Indian Affairs were already imposing on their culture.

Peter Matthiessen’s writing of In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, a relentlessly researched yet soporific 700 page book, has not freed its central character—Leonard Peltier—from jail, nor has Evan S. Connell’s Son of the Morning Starstopped the perennial flood of books that attempt to define an era through the dusty prism of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Egan’s book, however, is written with a delightful sense of irony and you can feel his bemusement at Curtis’s conflicted discipline, lack of self-control and his almost Calvinist sense of predestination. Reading it set off a flood of connections in my mind, along with the questions it raised.

In 1981, writer John McPhee wrote The Survival of the Bark Canoe, a study of Henri Vaillancourt, a man obsessed with making birch bark canoes today using exactly the same long forgotten methods handed down by Indians in the Northeast woods for the past several centuries. Vaillancourt’s preoccupation with duplicating those methods and materials is a mirror of Curtis’s need to find the spiritual as well as visual essence of North American Indian civilization at the point where it was being annihilated.

Curtis knew exactly where he was going and he had absolutely no idea where he was going. Born shortly after the Civil War, there were two pivotal events that cast his destiny. His father, a chaplain and private in the Union Army, brought home a camera lens, and Curtis used instructions from Wilson’s Photographicsto make a crude camera from a box. Curtis subsequently came across an engraving of a mass hanging of Indians—an image which stayed with him and haunted him forever:

“All my life I have carried a vivid picture of that great scaffold with thirty-nine Indians hanging at the end of a rope.”

Falling from a log one day after moving from Whitewater, Wisconsin to Puget Sound, and severely injuring his back, he was nursed to health over the course of the next year by a young girl, Clara Phillips, who would become his wife. The family soon moved to nearby Seattle and after establishing a portrait studio he took up mountain climbing. One day, while climbing on Mount Rainier, he rescued George Bird Grinnell, the founder of the Audubon Society and Field & Streammagazine, as well as C. Hart Merriam, cofounder of the National Geographic Society. That lead to an invitation to go to Alaska on the Edward Henry Harrimanexpedition in 1899, and to accompany Grinnell out to Montana in 1900 to observe and photograph the Blackfeet tribe. Grinnell shared Curtis’s budding fascination with Indians and their ceremonies and encouraged Curtis to do a grand project to photograph them. Curtis began what would become an all-consuming, obsessive project to document 80 tribes of North American Indians, with photographs, as well as by recording their songs using Edison wax cylinders. A series of serendipitous turns then lead Curtis to Sagamore Hill, Long Island, to photograph Teddy Roosevelt’s children and his daughter’s wedding. Five years into the project, with his own funds exhausted, Curtis realized he needed a patron and he found his Medici in J. P. Morgan, the railroad tycoon and art collector, whose business appointments were controlled by one Belle da Costa Greene. Egan delights in pointing out her eccentricities and coyly quotes her later as saying “I sent word that all…(marriage) proposals would be considered alphabetically after my 50th birthday.”

At first, Morgan turned Curtis down, yet it is a measure of who Curtis was that he would not accept defeat, so he began to tell Morgan how much it would help his ruthless reputation to support such an artistic and humanitarian project. When he walked out of that meeting, his bravado had paid off—he had been promised $75,000 ($1.5 million in today’s money) for a five-year project. In one sense, Curtis was triumphant, but Egan makes clear just how flawed a publishing model Curtis committed himself to—one which would haunt him for decades. The shorthand recounting is best told by Egan in this video.

In many ways, Curtis’s career can be told in a set of numbers: one divorce, two premature obituaries, 44,000 glass plates—enough to stack higher than the Flatiron Building—125 criss-crossings of the United States, 80 tribes photographed, 4,000 pages of text, 10,000 recordings on Edison wax cylinders, and the fact that one twenty volume set sold recently for $ 2.88 million dollars.

This was not the gonzo era of Hunter S. Thompson, with the sun hammering down on the blacktop of Route 160 on the way from Shiprock to Monument Valley. No pulling an Eldorado convertible into a Motel 6, no fueling up on peyote, gas and PowerBars. Curtis photographed with a 14X17” view camera, with delicate, yet heavy glass plates in wood holders. Making an image was a planned, deliberate process. The camera, tripod, lens and holder alone weighed more than forty pounds, and the depth of focus was measured in hundredths of an inch. A typical photo catalog from the 1890s shows some of the crude wooden view cameras of that era.

Yet through the Civil War, Matthew Brady shot with the far more cumbersome “wet” plate process in which the plates had to be coated with collodion and silver nitrate just minutes before exposing them to light. Brady, like Curtis after him, was consumed with an idea—to document the Civil War. And in some ways, his career presaged Curtis’s fuzzy math. He died penniless in the charity ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, having personally financed the making of that war’s greatest photographic record.

It wasn’t until 1881 that George Eastman formed what was originally called The Eastman Dry Plate Company, and it was with these thin sheets of emulsion-coated glass in 14X17” holders that Curtis set out from Seattle by train and wagon through the territories of the west, to see and photograph what remained of Indian traditions, dress and ceremonies, and to take a metaphorical census of Indians in lands that were not yet states, such as Arizona and New Mexico. There were almost no maps for where he was going, just rutted roads. One mistake, such as leaving matches behind, could spell disaster. All of this at a time when the Indians were fighting for their own survival, besieged by the loss of their hunting grounds, ravaged by new diseases, and forbidden by missionaries as well as covenants from practicing their own ceremonies. Yet Curtis was convinced he would succeed, and was determined to go from pueblo to pueblo, from arroyo to arroyo.

As a photographer, I want to know more about how Curtis seemed to be everywhere at the same time, how he packed the glass plates for shipment, and if he shipped them back to Seattle to be processed, catalogued, and annotated. Egan describes Curtis’s wanderings in America deserta, yet Curtis would disappear for months at a time and much remains a mystery, despite Egan’s research. Even with the massive monetary support from the House of Morgan, Curtis was forced to travel extensively to promote his project, and spent months in 1911 developing a traveling “picture opera” of Indian life, using hand-colored lantern slides, which included a lecture and live musical accompaniment. As well, in 1914 he was forced to try to raise additional funds by making a silent film called In the Land of the Head Hunters—it was the first feature-length film whose cast was composed entirely of Native Americans. Despite these substantial diversions of time and resources, Curtis continued to be driven to finish the remaining NAI volumes.

In the age of Photoshop, it is difficult to assess “ethics,” let alone what the definition of ethnography is, and that is where the awkwardness starts, and the ambiguity begins, as Curtis’s many supporters reach for modifiers and refer to the body of his imagery and field work as “romantic ethnography”. I would like to put that in perspective, not just in terms of how difficult Curtis’s task was to create technically perfect images, but in terms of death, for death was an ever present preoccupation of the era in which he lived, whether in the blood lust of North versus South, the annihilation of the Indian food chain in the wholesale slaughter of 70 million bison, or in the killing fields of the Great Plains, such as Wounded Kneeand Sand Creek.

On a clear evening in 1981, my wife handed me a wrapped box which, when I opened it, revealed two Curtis prints she had purchased for my birthday for $100 at the Daniel Wolf Gallery on 57th Street in New York. We immediately had them framed, and placed them in the vestibule of our house—a vaulting modernist glass space at complete odds with the images, but that was just the point. Everyone who walked in stopped abruptly and asked about the images of “Waiting in the Forest,” and “In a Piegan Lodge—Cheyenne”. Curtis had been on to something from the start, and what struck a chord with us in our own small way, had struck him speechless in an instant, for he knew he was too late, and yet he had to go forward, he had to record what was still there. It was his duty, his calling, his sense of being.

Curtis was literally riding into the unknown, and it is no wonder that he did not see his youngest daughter for more than thirteen years, no wonder that he had a breakdown, no wonder that Egan devotes much of the book to recounting the heroic assistants who stood with him almost to the end. When Egan first describes William E. Myers, he says he was “an uncanny linguist…(who) had an ear for the nuances of speech and dialect…his swift shorthand proved invaluable in taking down words for the dictionary-like glossaries Curtis was pulling together of languages that were falling out of use.” He stays with Curtis for decades, and Curtis writes such a sweeping and heartfelt dedication to him in Volume XVIII that “Myers wept when he read the dedication.” You sense that Egan is huddled there with them, and that you are not far behind. As for daughter Florence Curtis, Egan notes that “(she) was astonished at her father’s pace and his skill in the outdoors. He seemed to know every bird and fish, the name of every flower and fir and deciduous tree…for sleeping he weaved spruce boughs into a cushiony bed.”

The paintings of Indians by George Catlinare referenced by Egan, though the ones I have always found most haunting are those by Karl Bodmerin the Joslyn Museumin Omaha. Surely they romanticized their subjects as well. Considering his obsession with portraying the nobility of his subjects, I don’t believe that Curtis did anything intentionally to mislead. He was, simply, too late, and the daunting task he faced on day one was “where to begin.” Volume XIX was the most disappointing to him personally, as Oklahoma was the dumping ground of the Indian spirit, and the place where many of the tribes were sent to be forgotten, meek outcasts assimilated in a society controlled by missionaries. One of the most telling images is a portrait called “Wilbur Peebo—Comanche, 1927”. In his shirt and tie, and his short cropped hair, it is one of the most horrific images that Curtis captured, despite being a straightforward, artless portrait.

Curtis finished NAI within months of the start of the Great Depression in 1929. Coincidentally, Kodak discontinued glass plates that same year. J.P. Morgan died in 1913, and it is one of the large miracles of this impossibly improbable story that his son, Jack Morgan, continued to fund Curtis. When Volume XX was shipped to the printer, Curtis had received $2.5 million from the Morgans, an amount equivalent to $50 million today. Finally, in the early 1930s, he ceded copyright to the Morgan estate which just few years later sold the original photographic glass plates, the copper printing plates, and 19 complete, bound sets of NAI along with 200,000 gravures, to the Charles Lauriat bookstore in Boston, for the grand sum of…$1,000. In the midst of the worst economic disaster in the nation’s history, along with World War II, Korea, the Sixties and Vietnam, Curtis’s lifelong quest was completely forgotten. Curtis spent the waning years of his life shooting Hollywood portraits and was a cameraman and advisor at times for Cecil B. DeMille. He died of a heart attack in Los Angeles in 1953.

Nearly four decades years later, when his forgotten treasure was uncovered in the Lauriat bookstore’s basement, his life’s work underwent an extraordinary reassessment. Today, he is the most collected photographer in the world, and the total dollar value of his work is incalculable. More importantly, the importance of his work both as a photographer and as an ethnographer continues to redefine our sense of what one person can do, and to give us a picture of one of the most violent upheavals in our history—one that would have been lost forever if not for his vision, his unending obsession, and his deep personal bond with the ceremonies, culture and beauty of Native Americans.

Egan’s research uncovered many new facets of Curtis’s life, not the least of which was his obsession with the Battle of the Little Big Horn and the lengths to which Curtis went to obtain first-hand accounts from some of the Indian survivors. The ultimate irony of Curtis’s effort is that very few people have ever seen a single volume of NAI, let alone the entire set of twenty books. Instead, our opinions have been formed by digital reproductions and the few gravures we may have seen in galleries.

What is all the more remarkable about Curtis’s achievement was that it occurred at a point where photography was still in its infancy, when few photographers had ventured beyond the realm of their studios. William Henry Jackson had photographed the American West, and more than a century later Avedon would photograph drifters, ranch-hands and coal miners in a completely different vision called In the American West. Yet Curtis stepped off a cliff at the same time he vaulted into the rarefied clouds of ambition, when he set out in 1900 to make the most comprehensive record ever of Native Americans. No one had ever attempted anything like it, nor has anyone since. At the age of 60, fighting to finish his masterwork, Curtis’s final struggles to photograph Eskimos far above the Arctic Circle are best understood through his own description: “The wind picked up sections of the sea and threw it in our faces.” Then, Curtis dryly adds “One nice thing about such situations is that the suspense is short lived…you either make it or you don’t.”

At their pivotal meeting in 1906, as Curtis was leaving, J.P. Morgan stopped him, saying he had one more thing to add: “Mr. Curtis, I admire a man who attempts the impossible!” The same could be said of Timothy Egan, who has brought to life a complex, obsessed visionary, and made us understand the greatness of Curtis’s singular achievement.

August, 2013

A Biography of Eric Meola

Eric Meola’s graphic use of color has informed his photographs and his distinguished career for more than four decades. As an undergraduate at Syracuse University, he studied color printing and color theory with legendary instructor Tom Richards at the Newhouse School of Journalism before graduating in 1968 with a B.A. in English Literature and then moving to NYC in 1969 to work with Pete Turner as his studio manager.

Eric’s prints are in several private collections and museums, and he has won numerous awards including the “Advertising Photographer of the Year” award in 1986 from the American Society of Media Photographers. Showcasing a portfolio of his color images in its October 2008 issue, Rangefinder magazine referred to Eric as one of a “handful of color photographers who are true innovators.”

In 1972 he photographed Haiti for Time magazine, resulting in one of his most famous images, “Coca Kid,” which was included in Life magazine’s special 1997 issue “100 Magnificent Images,” as well as the ASMP archive at the International Center of Photography. His Time cover portrait of opera singer Beverly Sills would later be included in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery. In 1980 he had his first major exhibit in New York at the “Space” gallery in Carnegie Hall, and his signature red, white and blue image “Promised Land,” was chosen for inclusion in the permanent collection of the George Eastman House. In 1989 he was the only photographer named to Adweek magazine’s national “Creative All-Star Team”; and that same year he received a “Clio” for a series of images he made in Scotland for a breakthrough campaign featuring the outerwear clothing of the Timberland company. “Fire Eater,” his iconic image of the spotlit lips of a woman submerged in a tank of water, and commissioned by Almay cosmetics, was included in Robert Sobieszek’s 1993 book on advertising The Art of Persuasion. He made a spectacular series of panoramic images for the Johnnie Walker Company in 1995, which were included in an exhibit of his work in New York. A Canon “Explorer of Light,” he has lectured extensively, including at Syracuse University, Rochester Institute of Technology, Brooks (Santa Barbara), the Art Center at Pasadena, Parsons, the Academy of Art College (San Francisco), the George Eastman House, and venues including PPA, WPPI, and ASMP.

In 2004, Graphis Editions published his first book The Last Places on Earth, a look at disappearing tribes and cultures throughout the world. An exhibition in England of his photographs of Bruce Springsteen, which coincided with the publication of his second book Born to Run: The Unseen Photos (Insight Editions, 2006), was followed in 2008 by INDIA: In Word & Image (Welcome Books, NY), and an exhibit in 2009 at the Art Directors Club of New York. In 2011, Ormond Yard Press of London published his most unusual book, an oversize (18”x24”, 14 lbs.) edition of photographs of Bruce Springsteen—Born to Run Revisted—that was limited to 500 copies. Streets of Fire, his fifth book, was published by HarperCollins in September of 2012.

Updated: 2/26/15

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

You May Also Enjoy...

ColorLife

Alain Briot is one of the most successful landscape photographers working in the American Southwest today. His work is widely exhibited and collected. His new

Panasonic LX100

The New Pocket Camera of Choice There is a problem in the camera industry, and only a few companies rise above the rest to overcome