We are coming to a significant crossroad in the evolution of digital photography. There is a convergence of factors underway that is changing the way in which we perceive the merits and value of the equipment that we purchase.

On the one hand we have a rapidly flattening slope on the image quality side of the ledger, where it takes a serious additional expenditure to derive what is often only a moderate increase in image quality.

On the other we have the worst global economic environment in our lifetimes, which is causing photographers to more seriously evaluate the value proposition of their purchases than ever before.

The third hand holds the issue of numeric analysis vs. the evidence of ones eyes. What do we do when the test numbers tell us one thing and ours eyes tell us another?

This is the second of a multi-part series of essays that will appear here during the month of February, which will attempt to address these issues. The first article was titledQuality vs. Value. If you have not already done so I suggest that you read it before this one.

I also invite you joinour discussion forumif you’d like to express your thoughts on this and future essays in this series. Let’s have a dialog about it.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Abandoned – Antarctica, January 2009

Phase One 645 with 75-150mm @ 135mm with P65+ back

1/80 sec. f/16 @ ISO 50

Our world is filled with instances where measurements and the evidence of ones senses come into conflict. Audiophiles have long known that readings of THD and IMD tell one almost nothing about how an amp or other device actually "sounds", and when it comes to loudspeakers few would disagree that measurements are almost meaningless, and that the evidence of ones ears are all that really counts.

In photography, especially now some ten years into the digital era, we are once again faced with that same conflict – on the one hand those that judge cameras and lenses by the evidence of their eyes, and on the other folks that find MTF charts and lab test measurements to be their ultimate arbiters.

In late 2008DxO LabsintroducedDxOMarkwhich Ireviewed hereat the time. I have a lot of respect for DxO and spoke highly of DxOMark in my review. By way of full disclosure, I did some consulting for the company early on, and had been a beta tester in 2004 for theirDxO Optics Prosystem. For a year or so afterward I published a series oflens and camera reviewsbased on it.

But eventually I stopped relying on it because I was finding a growing disconnect between the results that I wasseeingfrom some equipment and the numbers being generated by Optics Pro. Eventually I returned to doing subjective reviews, which I have continued ever since. Nevertheless since then quite a few organizations have adopted the DxO Optics Pro testing system, includingPopular Photographymagazine in the US andChasseur d’Imagein France.

When the company’s DxOMark pages first went online last November I was positive about it because I felt that the engineers and scientists at DxO really know their stuff, and that the industry could use an impartial technical yardstick by which to measure digital camera performance.

Since then though I have become increasingly concerned, because their DxOMark metric provides people with a number, precise to within one decimal point, but which has become misunderstood by many.

Firstly, such a level of precision is essentially meaningless. Statisticians call itspurious precision, since it creates an impressions of accuracy that isn’t at all relevant.

Does a ranking of 62.3 really differ in any meaningful way from 63.8? No, not at all. In fact DxO points out that a measure smaller than 5 is hardly perceptible, representing just a 1/3rd stop difference.

More specifically, over time it has become clear to me that there is an even greater flaw to DxOMark, and that is that it does not correlate one of the most important metrics,resolution, with its other measurements.

This scale is based on three underlying metrics, Color Depth, Dynamic Range and Low-Light ISO.

The above quote from the DxOMark web site indicates the nature of the problem. Sensor resolution is not one of the metrics included. This means that a 12MP camera that scores a couple of points higher than a 24MP camera will be judged by most people as being superior by its DxOMark rating, even though, as we now know, less then 5 points difference is not even visible. Yet, camera one has twice the pixel count (1.4X the resolution) of the other. This flies in the face of both experience and common sense.

And finally, price is not a factor which is included in the DxOMark score, though in the real world it most certainly is a major consideration for most people. Will you pay thousands more for a barely visible difference in image quality? Most people won’t. SeeQuality vs Value.

______________________________________________________________

Medium Format Under the Gun – Wrongly

On Feb. 3, 2009 DxO put the cat among the pigeons by publishing rankings for four of the industry’s leading medium format cameras and backs, the Hasselblad H3DII, Leaf Aptus 75s, Mamiya ZD, and Phase One P45+. Putting aside the Mamiya ZD, which doesn’t belong in this grouping, these three backs are at the pinnacle of today’s photographic marketplace, both in terms of price and performance. Thousands of professional photographers around the world have purchased these systems because they have tested and evaluated the images which they produce and have found them to be superior to what can be produced with the best DSLRs. This is especially so in the fashion, architecture and publishing world’s where quality is often factored above cost, and where large layouts and prints are demanded. Many of the world’s leading fine-art photographers also have made the considerable financial commitment to equip themselves with such systems based on in-depth personal evaluation.

It should be noted that with the except of this site, there are very few venues which report on medium format digital on a regular basis. This means that unlike in the DSLR world, where photographers have lots of magazine and web site reviews to use as a jumping off point, with medium format backs and cameras pros tend to base their buying decisions almost exclusively on the evidence of their own eyes.

But – to continue – as you will read onDxOMarkall three of these newly tested medium format systems rank lower than either the new Canon 5D MKII or Sony Alpha 900, for example.

Now both the Canon and the Sony are very fine cameras. But as someone that has recently shot more than 6,000 frames with the A900, but who has also has owned a Hasselblad H2 with P45+ back for a couple of years, I can tell you that ranking the A900 higher than the Phase One back is simply wrong-headed. It’s a wonderful camera, and produces some of the best images that I’ve seen from any DSLR, but the P45+ is clearly superior when it comes to making professional quality prints.

I am not disputing DxO’s numeric test results. They show what they show. But the numbers themselves simply do not correlate with the reality that I and many other knowledgeable photographers see, and which literally thousands of professionals around the world experience in their work on a daily basis.

Not only is this the case because resolution is not factored in – in the sense of number of pixels, but also partially because MF backs do not have anti-aliasing filters and therefore are capable of resolving greater detail than cameras (almost all DSLRs) that smear resolution by using an AA filter over the sensor.

I think though that the main problem is that DxO is analyzing raw camera data, which does not include any correction of fixed pattern noise. DSLR cameras remove these noise sources before storing their raw data. Medium format cameras do not. DSLRs also apply a lot of noise reduction algorithms before storing the data. I’m not sure about Hasselblad and Leaf, but I know for a fact that with Phase One digital back files both fixed pattern noise and other forms of noise reduction are applied in the raw processing software, such as Capture One, rather than on-chip.

Therefore comparing an uncalibrated and unprocessed medium format raw file with a raw file from a DSLR is like comparing a baked and an unbaked cake with one another… one of them will likely taste and look better than the other. Nikon, for example, does a lot of on-chip noise reduction to their D3 and D3x raw files. Hence an analysis of this data is going to be very misleading and incorrect if you compare it to a medium format raw file with no noise reduction applied. In such a comparison Nikon files will show very little noise, whereas the MFB files will appear extremely noisy, and If you just look at the uncalibrated and unprocessed data this converts as well into lower dynamic range numbers – something which is quite obviously not the case in the real world.

I therefore am very dubious about the validity of DxO’s medium format back results, even though their test methodology is self consistent. Unbaked cake anyone?

There is also no room in these numbers for any form ofsubjective quality evaluation. Just as an audiophile can tell when one amp or speaker sounds better than another just by listening, and doesn’t need a THD measurement to tell them which is better, so too do experienced amateurs and pros know when the evidence of their eyes are is contradiction with a numeric test.

Trust your eyes, because they are ultimately what is used to judge the final output – not a test bench.

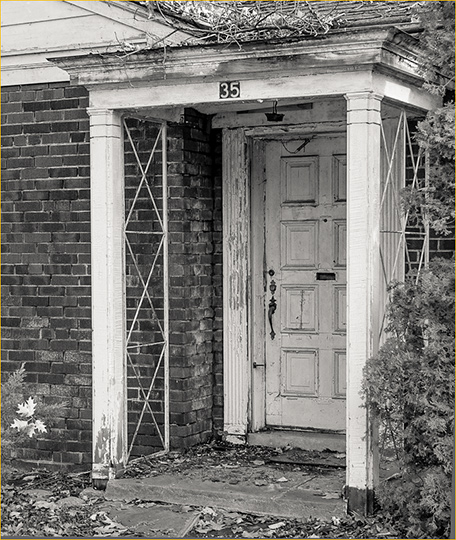

Morning Opening – Buenos Aires, Argentina. January, 2009

Sony A900 with Zeiss 24-70mm f/2.8

1/80 sec f/3.2 @ ISO 200. 70mm

______________________________________________________________

Where Do We Go From Here?

Are DxOMark and possibly other numeric tests invalidated? Is subjective evaluation the only appropriate way to judge equipment?

I don’t think either is true. There’s room for both, but both require that the consumer of the information apply judgment and intellect to the evidence presented. When looking at numeric analysis, such as DxOMark, one has to inquire as to the nature of the things being measured, and appreciate both what has been measured and what hasn’t. And when it comes to considering a subjective evaluation one either needs to feel confident in ones own experience and ability or trust that of the person being listened to.

My fear though is that the web forum fanboys are going to jump all over these DxO results and make inappropriate conclusions. But, what else is new? Pros and serious amateurs will likely continue to make their judgments and life will go on. Twas ever thus.

______________________________________________________________

A Lesson From the World of High-End Audio

Digital photography is a relatively new technology. High-end audio is a mature one. Possibly there are lessons to be learned by one from the other.

As the audio world matured during the 1970’s through the 80’s the technical specifications became more and more refined. THD (Total Harmonic Distortion) numbers became lower and lower, with companies vying with one another for numbers with more and more zeros – .001% being a target that I recall. The Japanese component makers became the leaders in this area, producing gear with ever "better" specs – typically through the application of large amounts of negative feedback, which measured well but sounded dreadful.

A great many American companies though became disenchanted with numeric analysis and simply started designing gear that sounded good, regardless of how it measured.

Increasingly, as the numbers became lower music lovers and those with so-called "golden ears" became increasingly dissatisfied. The reason for this was that there didn’t appear to be any correlation between the specs and measurements and how a piece of equipment actually sounded. In fact, there were many instances where amplifiers with quite poor specs demonstrably sounded better than ones with lots of zeros in their test results.

There consequently developed a schism between customers and companies who "went by the numbers" and those who believed that measurements only told part of the story at best, and that the only thing that counted were how a piece of equipment actually sounded. The journalsStereo ReviewandThe Absolute Soundin some ways represented these two ends of the spectrum.

Ultimately sanity and the golden ears won out. Low power Class A amps using vacuum tubes (valvesin UK parlance) often sounded far sweeter than transistor and IC equipment, though they measured much poorer in instrument tests. The reason turned out to be that some forms of measurable distortion actually sounded better than in equipment which attempted to remove all distortion completely. (The human ear interprets even-order harmonic distortion as musical, while even a slight amount of odd-order THD is harsh sounding. Both measure similarly but sound vastly different.)

It should be enough to mention that in the end thelistenerswon out over themeasurers, and today it’s rare to find anyone that enjoys and discusses high-end audio who cares a fig about measurements. It’s all about the sound.

Are we going to encounter the same thing in high-end digital photography? Now that the technology is somewhat maturing are we going to find that there’s more to how a sensor performs that can be can be told by instrument measurements alone? I believe so.

I’ll now leave this debate to another day, but I urge serious photographers not to succumb to the temptation of reducing the evaluation of our tools to simple technical measurement. Just as was the case with audio, we don’t know at this point what all of the the factors are that influence how a particular camera’s sensor will perform. There appears to be as much art as science in this, and so let’s let things evolve a bit more before we start accepting too many absolutes. To do so would be to deprive ourselves of what might turn out to be some very fine instruments.

February, 2009

You May Also Enjoy...

Mountain and Reflection

Please use your browser'sBACKbutton to return to the page that brought you here.

Field Testing the Zeiss Touit 12mm f/2.8 Lens

IntroductionWhen the Dutch representative of the Zeiss lenses asked me whether I am interested in testing the Zeiss Touit 12mm lens, I immediately agreed. Zeiss