More on Clichés and How to Avoid ‘Em

Good morning! Today I’d like to do something I do every once in a while, when it’s merited — share some reader mail. Every week I get responses to the columns I write here onThe Luminous Landscape. The responses to last week’s column,Eschew Clichés, were so interesting that it would be a pity not to let you read a few of them. But first, a really astonishing development in the celebrated mystery of the nun’s hand:

Mike,

In Donna Ferrato’sNun in Venice, I was also taken by the peculiar position of the nun’s hand, in that she holds it in what seems a rather uncomfortable degree of flexion, with the small digits just slightly spread laterally. I then realized that this was not an expressive pose, but likely the result of a neurological injury.

The nun has what is called a "wrist drop". This is due to an injury of the main nerves (called the brachial plexus) which innervate the upper extremities. This injury is specific to a particular portion of the brachial plexus (the posterior cord), resulting in her readily identifiable injury. These injuries are typically caused by 1) shoulder belts in high speed auto accidents or 2) a fall onto a shoulder with great force. There is one other possibility from a causation standpoint — lead poisoning — but that would be unlikely. In Hippocrates’ time this might have been the most common cause of this ailment. However, there were many fewer auto accidents in his day!

This has actually made the photograph even more interesting to me, and I wanted to share this observation with you.

—DR. PATRICK HYMEL, M.D.

MJ responds:This is indeed interesting, and not only as a "finding of fact" so to speak. Because if you’re right and it’s true, then one thing it means is that my "characterological" interpretation of two weeks ago — the nun’s hand as an expression of personality or mood — is not only wrong, but also wrongheaded!

That’s very interesting to me. The question it raises is, do we each, as viewers, have the right to our own reactions to photographs — even if we’re wrong?

I’m reminded of two of my students’ disparate reactions when shown a photograph of Adolph Hitler. One said, "My great-uncle died at Dachau." The other (in another class) said, "Mmm. Say what you want about the Nazis, theydefinitelyhad the coolest uniforms." Those are only two of many possible responses to a picture highly charged with meaning; imagine the even broader range of interpretations by which different people could respond to subtler, more open-ended pictures.

The quality I’ve tried to cultivate as a viewer of photographs is an unmediated openness to my own reactions and feelings. In other words, as I wrote once a long time ago, "I have a right to respond to art as if my exposure to it were a significant occasion for me." This is an important idea in appreciating art, I think. As my friend Jim Schley taught me, when you read a book, for example, it’s aneventin your life! Granted, the book has been sitting there waiting for you. It’s old news to people who read it years ago. But this is the first timeyou’veread it, and if you’re not willing to treat the experience as an occasion, as something that’s going on in your life at that specific time, then I think you cheat yourself out of an important part of the experience of reading. It’s the same with art. I certainly remember vividly some of my more formative experiences in art galleries and museums; in many cases, I have powerful memories of my first exposure to certain photographers.

I don’t want to write a whole column about this topic, because I got so many interesting responses to the column about clichés and I want to get to those. But there is an essay about this subject — the nature of responses to pictures, I mean — in my forthcoming book,The Empirical Photographerfor those who are interested. Meanwhile, are there any other medical doctors out there who might want to weigh in with "second opinions" to Dr. Hymel’s diagnosis?

"Eschewing Clichés"

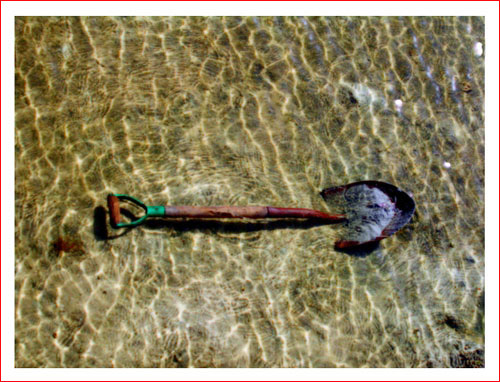

Photograph byNick Ledford(letter below).

Dear Mike,

I enjoyed your piece about photographic clichés. The fact that Ken Croft has expressed doubts about his motives for taking photographs does him great credit. Most camera club photographers I have met here in England have no doubts whatsoever about their motives — they take pictures to please the competition judge. Their pictures conform to a set of well-known predetermined rules that are continuously reiterated by the judges.

It’s like entering your dog in a dog show or your best tomatoes in a horticulture show. The product has to conform to an arbitrary and artificial set of rules to which all entrants tacitly agree, and the end result is a certain "look" or cliché to which all entrants aspire. Some photographers spend large amounts of time and money on this seemingly mindless activity in which creativity and personal preference or expression can play little part.

Why do they do it? In their competitive desire to win, these photographers are taking the easy way out. They go through the motions of making pictures without confronting any of the difficulties associated with looking at the world, working out how they feel about it, and trying to make photographs that reflect how they feel. That can be very difficult to do. It’s far easier to make pictures conform to a simple set of rules.

The result: wall-to-wall photographic clichés!

So what are these "English" rules? Well, for landscapes you must include no "modern" technology. The judge will have traveled to the competition in a car, but he won’t want to see any cars in your pictures. He will certainly live in a house, with electricity, but will, with equal certainty, mark down any pictures that have electricity pylons or buildings in them, unless the buildings are old and quaint. Old technology such as windmills is allowed, but nothing from the last 150 years.

Your picture must have a center of interest, but it must not be in the center of the picture! Play safe and put it on a "third."

If you are going to have any lead-ins for the eye, make sure they go from left to right. In England, apparently, people can’t move their heads from right to left. Did you know that? Apparently it has something to do with the way we read.

For subject matter, if in doubt, stick to sunsets over water, or moving water taken at slow shutter speeds.

You prefer taking pictures of people? Here is a winning formula that will definitely find favor with the judges. It is called the "f/4 double portrait." First, find two outlandish-looking people. Punk hair styles, safety pins through their noses, tattoos, etc. Take your subjects to a socially deprived area where these is graffiti on walls, peeling posters, etc. Subways are good. Use a 35mm camera set to f/4 and held horizontally. Frame one person, head and shoulders only, on the left, in the foreground, in focus. Place the second person on the right, further back and out of focus.Voila!This formula works equally well in color or black-and-white. It neatly solves the problem posed by the long 35mm aspect ratio when used for portraits, and gives the impression that you have a social conscience when all you are doing is exploiting someone’s bizarre looks.

— ALAN CLARK

Dear Mike,

I have read many of your columns; some I have liked and others I have disliked (not violently, mind you). But your recent column about rising above the photographic cliché was different. It was a message I needed to hear, and you spoke to me directly. I am a "mere" amateur, not a professional by a long shot, so I don’t shoot to make money. Yet, if I really examine my motives in pursuing my photography, I must admit that I have generally tried to emulate the clichés of others. That’s fine for learning the craft, I guess, but it’s time to move beyond that. After reading your column today, I am going to have to rethink just why I have a camera. Perhaps I’ll find something — who knows?

Anyway, many thanks for an excellent column and message. Keep ’em comin’!

— DARYLL WILLIAMS

Dear Mike,

Good essay this morning. Of course, producing cliché shots is a useful exercise on the road toward technical competence — mimicking the technical and compositional processes of others helps in learning the basics. But technical mastery brings the opportunity to begin bending technique and confounding expectations, which is much harder to accomplish. Really, connecting the dots, we could go back to the essay in your latest37th Framenewsletter and ask ourselves the question "Why do I photograph?" The answer would often reveal much about one’s own vision, be it clichéd or original. (If the answer is "To produce color landscapes worthy of the Sierra Club calendar," well, we’re talking cliché, but even that’s not always bad.)

As far as personal tastes go, I knew that I’d started moving beyond clichés when I stopped entering photo contests. Well, okay, I still enter now and then, mainly because United’s in-flight magazine has an annual contest in which one of the prizes is two business-class tickets to anywhere they fly, which is a personal fantasy for me. But I’ve stopped wondering why I never win; I reckon it’s because my photos might be more original (i.e., less appealing to judges) than most peoples’. At least, that’s what I tell myself!

I also knew I was moving past appreciating clichés when, at a Carmel gallery, I much preferred a pictureofBrett Weston (taken by someone I’d never heard of) to any of the picturesbyBrett Weston. Still wish I’d bought that photo of him, peering up from the trap door leading to the underground window alongside his pool, talking to one of his nude swimming models. It was only nine hundred bucks, but that’s a lot of scratch to me.

As much as I pretend to disdain clichés, though, when I’m in Venice (Italy, not California) next week, I will have difficulty resisting that shot of the moored gondolas against the blue sky. That’s the thing about clichéd shots: we both know they’ve been done a thousand times, but still, when someone sees that print on my wall, their reaction will be "Wow, what a great picture!"

—DOUGLAS KINNEAR

MJ responds:I admit it, Doug, I’ve taken that gondola shot too.

Dear Mike,

I read your column here every week, and enjoy it immensely.

Your essay about clichés in photography struck a chord in me because I recently found myself in a situation which forced me to snap out of shooting clichés, or at least try to. As we amateurs advance in our skill, we have no real way of knowing if our work is "good" unless we compare it to something else that’s "supposed" to be good. Hence the pride when someone says "it looks like a postcard" or it "looks professional." At least we know we have reached that standard, which is good to know.

The question is, how do we go beyond that? For me, it started happening when I recently drove 6,000 miles across the U.S. from Seattle to Florida. I used a Sony DSC-F717 to shoot scenes along the way, and I posted them on my web site every night during the trip for the enjoyment of my friends and photography students who were "cyber-travelling" with me.

After about a week, I found myself struggling each day to find new subject matter that didn’t look like the pictures I had already taken. I found myself saying "not another tree!" or "not another snow-capped mountain peak!" or "not another cow in a paddock!" I had to really start looking hard to find new subject matter, or at least to look at familiar subject matter in different ways.

Photographers have been including their conveyances in landscape pictures to provide scale and context for a long time. Photo byCraig Norris.The moral of the story is that it helps if we’re forced by circumstances to break out of old habits and to do things differently. Clichés are quite acceptable, and may be necessary, for beginners. It’s like practicing scales when learning the piano. You have to get a "pass" on the standard pieces. But sooner or later we have to start playing our own chosen music. Preferably original music.

And that’s one of the things I like about photography — it compels me to look at the world in new ways, to reallylookat the world, and notice how it changes when I vary my viewpoint and relationship to it. Seeking that "peak" in the beauty as I tune my viewpoint up, down, left, right, closer, farther, wider, tighter. But most importantly, it forces me to go out into the world, away from my everyday life, to where everything is new and unusual to me. Escaping a clichéd life is the first step in avoiding cliché photographs.

—CRAIG NORRIS

Dear Mike:

Nice piece on clichés in photography. Thank you, especially, for not once using the phrases "pushing the envelope" or "thinking outside the box."

You might take the whole thing a little further. I’m on shaky ground here, just sorting some of this out for myself, so I’ll try to keep this as clear as possible within the bonds of my own confusion. Originality in art (and I include photography) means far more than simply avoiding clichés. That’s what makes it so darned hard to accomplish. That fact also helps explain why art by rebellious teenagers is usually clichéd in its own ways, and (sorry to disagree) little more likely to be original than the art of their tired teachers and parents.

So how to do it? Create original, worthwhile photography, that is? Metaphors come to mind. Some of the best artists I’ve known (I mean known personally, not like Van Gogh or anyone like that) see their art as a process of continuous exploration, almost geographical in nature. You find a part of the aesthetic universe that looks appealing and you keep trekking on through. Sometimes all you find is new terrain that looks a whole lot like Kansas or New Jersey. Occasionally, if you’re patient and hard working, you make interesting or even amazing discoveries. What’s key here is discipline: the dedication to keep working in sensible directions rather than striking out randomly and wandering like a drunk. Also essential is the ability to recognize interesting terrain when you see it.

How do you do this as an actual photographer in the real world? That’s the billion-dollar question, isn’t it. Despite my deep suspicion of academe and its influence on the arts, I’m told a good MFA program (= two years of hard, directed work with a mentor) might be one way for people with money and time. In much the same way, a bad MFA program would be terrible, worse (and much more expensive) than camera clubbing. In any case I don’t have the resources for that.

Another way might be to form your own critique group, much smaller than most camera clubs and totally exclusive. Many writers I know work in such groups, and they’re very effective, at least with the right people. Only a few artists I know also have critique groups, perhaps because our culture has much less aesthetic agreement about visual art than about writing.

OK, enough already. You got me going, though.

—BOB KEEFER

Riley Pond, a hand-colored photograph byBob KeeferYour recent article "Eschew Cliché" mirrored thoughts I’ve been having about my own photography. My viewpoint is a little different from yours, but it’s the same idea. I still consider myself an amateur and have been trying to learn as much as I can lately about photography. As of right now, I truly don’t know my own style. As a student of photography I’ve been paying particular attention to what makes the great photographers good, in my opinion. These attributes and styles are making their way into my images.

I do believe that the more pictures I take, the more of my style will be in them. I find a comparison to this in the prose of one of my favorite writers, Jack Kerouac. In his early novels his writing characteristics clearly go through the patterns of the many greats that he admired. It was only in his later work that his own style clearly emerged. From what I understand, Jackson Pollack went through some of the same type of influences before emerging with the "splatter" paintings that he’s famous for. I think some of us are not necessarily trying to please others, but subconsciously trying to imitate what we think are qualities in other photos.

Thanks for all the wonderful articles.

— NICK LEDFORD

Dear Mike,

After I read your article I did my usual self-introspection to see if I am one of those cliché-type photographers you were talking about. I’ve decided that I am and then I decided that I should do something about it. I primarily photograph horses, Appaloosas to be specific. In the horse world, most everybody who wants to sell anything is shooting the same way. So there I am, reading your article, and I scroll down to the SMP book selection. What do I find? A picture of a man standing on a Leopard Appaloosa. It wasn’t exactly a lightening bolt, but for a minute there it did feel like the powers of the Universe were just a little too focused on me and my thoughts. Anyway, I get the point, and short of having my clients stand on their horses, my new self-assignment is to at least recognize the clichés. If I am successful, then I will work on eschewing them.

Thanks for the motivation!

— ANNA CAPALDI

MJ responds:Yes, Anna, I think the Universe is definitely trying to tell you something!

Finally, this came in from Kevin Bjorke, in response to my puzzlement over the glass globes that sometimes appear in pictorialist photographs:

Dear Mike,

The glass globe is an iconic reference to Dutch portraiture of the 1500s and 1600s, in which reference to the new optics industry indicated an interest in things new and scientific. It also indicated an interest in similar issues by the portraitist, a fact which has been construed by some (most famously David Hockney) to suggest that artists around this time accepted optical tools into their workshops, which in turn led to the strong explosion of "realistic" painting at that time (spreading from Holland to the rest of Europe).

Also, the globe had powerful social significance, because it indicated that the power of being iconified yourself — of being the subject of a portrait — was moving away from the ultra-powerful church and state authorities (saints, kings, and nobles of various sorts) and into the sphere of growing economic power — a connection to the optics industry usually meant a connection with telescope, navigation, commerce, shipping, and money. So we see it as an emblem of the rise of the merchant class.

The pictorialists (most infamously William Mortenson) just picked up all of the trappings left behind by those older traditions. Whether they were really aware of themeaningof such trappings is left open to question. But to a degree, they did — they were attempting, as the earlier painters had, to imbue their subjects (and themselves) with an illusory connection to power and substance.

— KEVIN BJORKE

Thanks to everyone for writing, and to Patrick, Alan, Daryll, Doug, Craig, Bob, Nick, Anna, and Kevin for giving me permission to reproduce their letters, and, in the case of Bob, Nick, and Craig, their pictures.

Next week: The Book, Boss, the Book!

— Mike Johnston

Want to read more? Go to the SMP Archives

Please support this column by subscribing toThe 37th Frame,Mike Johnston’s print newsletter for photographers.

Mike Johnstonwrites and publishes an independent quarterly ink-on-paper magazine calledThe 37th Framefor people who are really "into" photography. His book,The Empirical Photographer, is scheduled to be published in 2003.

You can read more about Mike and findadditional articlesthat he has written for this site, as well as aSunday Morning Index.

You May Also Enjoy...

An Amazon Portfolio

In April, 2007 together with world famous photographer Jay Maisel, colour management expert Andrew Rodney, and naturalist Fiona Reid, I lead anexpedition workshopon a riverboat

Aspen Canopy

The Sky's the Limit©Miles HeckerCLICK ABOVE IMAGE TO SEE GOOGLE MAP LOCATION SEASONS County Road 12 is a well graded gravel road that starts on