20 April, 2012

Two years ago today, I was tremendously privileged to land Space Shuttle Discovery after commanding her on her penultimate mission. It just so happens that Discovery was transferred to the Smithsonian yesterday and today is open for public viewing in the Udvar-Hazy center of the National Air and Space Museum. It seems fitting then that I write this post now about my photographic experiences onSTS-131.

ISS over Chicago – Imaged during our “Fly Around” maneuver after undocking.

The ISS is an incredible engineering feat .

My friend, African wildlife photographerAndy Biggs, asked me to write down some thoughts about photography in orbit. To perhaps capture some of the lessons learned, difficulties, and challenges of photography in an unfamiliar, and unforgiving environment.

Discovery w/Leonardo MPLM in the cargo bay during our rendezvous and docking with ISS. She looks great over the plains of NW Tibet.

The dark round item just forward of the starboard payload bay door/radiator is our Ku Band antenna. This critical equipment failed on Flight Day 1.

It was supposed to be used for high data rate communication and as our rendezvous radar.

One thing NASA does really well is contingency planning.

We had simulated this major failure many times and were well prepared to use other tools to get the job done.

My crew and I were very serious about attempting to capture as much as we could of the beauty and wonder of being in space. After all, we were entrusted by the taxpayers, to be in a unique position and to image things that most people would never see first-hand, so we really wanted to do well and capture some great images. I hope that we didn’t disappoint. One disclaimer, although I shot most of these, the images credits are all NASA’s.

Aurora Australis – Captured above New Zealand. Nikon D3s, ISO 3200, 3 sec, f/2.8.

The aurora was fairly active during our flight. It has been even more so lately due to solar storm activity.

Check out this YouTube video shot by my colleagues on the ISS last autumn.http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmQrRC6lerk

NASA does a wonderful job, and spares no expense, in training astronauts to be photographers. I was lucky. My wife is a photographer and so I had a little experience beforehand. I’d also met some great photographers over the years at the Kennedy Space Center. I was picked to be the lead Photo/TV crewmember on my first mission, STS-122 in 2008. As the Commander on 131, I needed to delegate that responsibility to another crewmember, but due to my interest in the subject, I always stayed aware on the topic. We spent many, many hours in classes, field training, and in simulators using the equipment that we needed to master. Our instructors prepared us very well, and when we launched, everyone was more than prepared. There is very little time for on-the-job training, so knowing the equipment and procedures ahead of time was critical if we were to avoid making mistakes (our crews take great pride in minimizing errors – even photographic ones).

Several months before launch, Nikon came to us with some prototype D3s camera bodies. We weren’t allowed to use them outside the lab, but even in that limited environment, it was obvious that the low light, high ISO capability in space was going to be a real game changer. I worked hard with the shuttle program and engineering folks to get those cameras onboard – along with some new glass as well. As with everything that flies in space, certifying it was no easy task. In the end though we were able to supplement the impressive suite of equipment that we were carrying, and the stuff already on the International Space Station (ISS), with a few D3s bodies. That decision really paid off.

For the first time, we were able to capture images that we never thought possible. Consider this image of the Milky Way. I shot it out of the cockpit window during our undocked timeframe. We saw the Milky Way, quickly darkened the cabin, and then mounted the camera on one of many articulating support arms (there are numerous fixed mount points scattered about the crew module) that we had available.

The fixed points and articulating arms were great to hold a camera in position, but weren’t a rock steady support. Vibrations induced by fans, jet firings, and other machinery were transmitted through the structure of the shuttle to the camera. This caused some difficulty getting sharp images. I tried to anchor myself really well and provide a little “human damping” similar to what one would do with a long telephoto lens.

In any case, this is a really unique frame. The coastline you see is the coast of India. Note that the city lights are blurred due to having the shutter open for 4 seconds (in that time we traveled 20 miles over the Earth’s surface). The stars, however, are not blurred at all. We were in the Inertial Attitude Hold mode so our attitude relative to the stars was constant. The colors you see are exactly as the camera captured them. You can make out the different layers of the atmosphere and if you look closely, you can see stars shining through the atmosphere. Note how thin our atmosphere is.

Milky Way from Discovery Flight Deck.

Nikon D3s, 14-24 f/2.8 @ 24, ISO 9000, 4 sec, f/2.8

Along with the stunning images we took of subjects outside the confines of our orbital home, the improved high ISO capability also allowed us to capture life inside the station and shuttle with just ambient light. Never before (at least without several strobes or a lot of noise) were we able to photograph well exposed interior shots. Look at this shot of Dottie Metcalf-Lindenburger in the Leonardo Multi-Purpose Logistics Module. I used just a little fill flash at ISO 1600 to take catch Dottie demonstrating what legs are good for in a micro-gravity environment – carrying things.

Dottie in MPLM – Nikon D3s, 28-70/f2.8, ISO 1600, 1/125, f/2.8

Here’s another good interior shot taken with no flash. It shows some of the combined crew having ready to have dinner in the Unity (Node 1) module. We tried to have at least one meal a day with everyone. This image does a decent job of capturing life in space.

Crew in Node 1 – Nikon D3s, 14-24, ISO 1100, 1/30, f/2.8

Here’s another good interior shot with no flash. It shows some of the combined crew having dinner in the Unity (Node 1) module. We tried to have at least one meal a day with everyone. This image does a decent job of capturing life in space. See the Speed Limit sign?

Here is another shot using ambient light only. It shows the four women onboard at the robotics workstation in the US Lab, Destiny. Incidentally, STS-131/Expedition 23 was the only time ever that four women have been in space simultaneously. Dottie M-L, Naoko Yamazaki and Stephanie Wilson were on my crew and Dr. Tracy Caldwell Dyson was a member of ISS-23. This shot was taken during a break while they were moving the MPLM robotically from Discovery to the ISS. Note how “busy” the lab is – lots of equipment.

Crew in Lab – Nikon D3s, 24mm, ISO 3200, 1/20, f/2.8

Occasionally I used a small camera mounted LED illuminator for a little fill and to provide a catch light in the subject’s eyes. Here’s another a snap of Tracy and Soichi Noguchi clowning around during our cargo transfer operation (this activity took up most of our time – see the “bungee jail” to Tracy’s right and all of the bags behind it).

Tracy and Soichi – Nikon D3s, ISO 1600, 1/125, f/2.8

Using reflected light from Earth as an illumination source is a technique that not many have been able to experience. Here the colors of the Mideast, eastern Mediterranean, and Red Sea are reflected in the payload bay and the wings. This image was taken on Flight Day 2 during our inspection of the heat shield for any launch damage (this procedure was performed on all flights after we lost Columbia and her crew in 2003). On the left side of the frame is the robotic arm end effector and wrist joint. The arm was used to lift the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) which is the long boom seen running down the starboard sill. In this image it’s easy to see Israel, Syria, the Sinai, and most of the Nile river delta. It’s hard to imagine all of the strife in this beautiful area when viewed from this vantage point.

Nikon D3s, 14-24 @ 14mm, ISO 200, 1/750, f/8

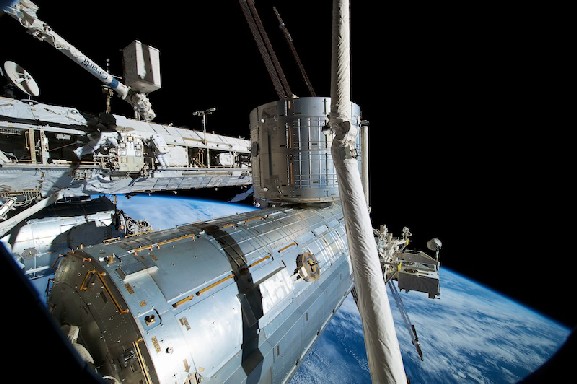

Here’s another frame of the same area taken a few days later while we were docked at the ISS. This one was taken from the Cupola module which was installed on STS-130 a few months before our arrival. Note the mostly empty bay. Leonardo was attached to the ISS at this point. The only remaining payload was the Ammonia Tank Assembly which you can see mounted on the cross-bay carrier at the back of the bay. The station robotic arm is in place to move the tank to the ISS during one of our three space-walks.

Nikon D3s, 28mm, ISO 200, 1/1000, f8

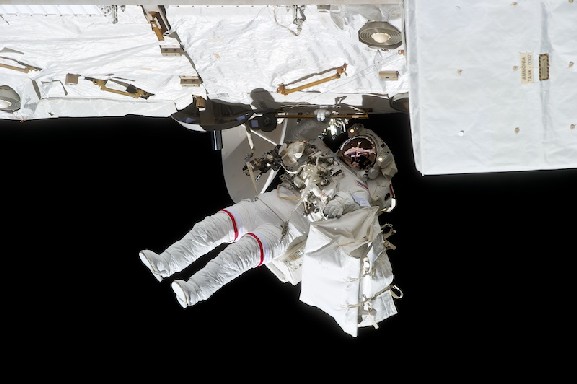

While living and working in space was a tremendous experience, it also presented us with many challenges. Some of which aren’t so obvious. Photographically speaking, there were a number of hurdles. The dynamic range of the subject was potentially huge. The darkest darks you can imagine along with the brightest highlights. With no atmosphere, there is probably another stop or two of light on bright subjects. I would guess that the dynamic range of some scenes approaches 16 or 17 stops. Here’s a shot of Rick Mastracchio outside during one of the space-walks the sunlit EVA suit and thermal blankets is a huge difference from the blackness of the background. This image had some really badly blown highlights which I was able to recover in post-processing.

Nikon D3s, ISO 200, 1/800, f8

This shot also presented some interesting lighting challenges. It was taken during orbital sunset over the terminator on earth. Note the color of the solar arrays with the low sun reflecting on them, the dark earth on one side and the super bright backlighting (with major blown highlights). The module you see here is the European Space Agency’s Columbus lab. We delivered it on STS-122 in 2008.

The other challenge that this shot demonstrates is rapidly changing light conditions. At 17,500 mph (that’s 5 miles/sec !) you get an orbital period of 90 minutes. That’s a sunrise or sunset every 45 mins. Light conditions like in this shot last for, literally, only a few seconds. Again, not much time for OJT.

Nikon D3s, 14-24@14, ISO 200, 1/90, f/4.8

That same speed also made it tough to be in position, with the equipment ready to go, in order to image specific places on earth. When you cross continents in minutes, you don’t have long to get a shot of your hometown…if it isn’t covered by clouds. When you did get there, you had to shoot at really high shutter speeds to avoid blurring the ground. The old rule-of-thumb of 1/(focal length) is far too slow. We were very busy, with our daily schedule filled in 5 minute increments, so I unfortunately missed most of the opportunities to grab frames of my favorite spots.

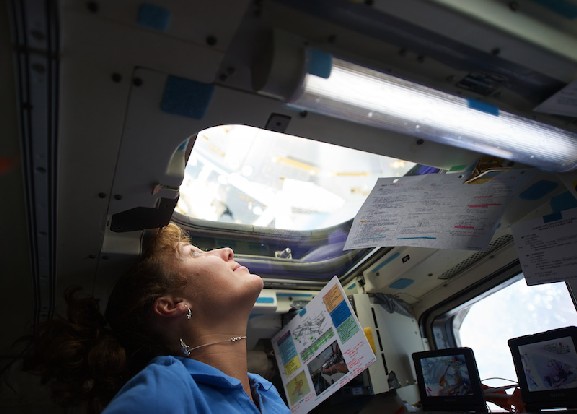

Anyone that has tried to shoot through a scratched up airliner window knows how difficult it is to get a good shot. Shooting through the thick and multiple panes, of a spaceship window (yes they’re scratched up too), is particularly challenging. Making sure you hold the front lens element parallel to the window is critical to avoid ghosting. Forget about it if there is any light shining on the window. Take this image. It shows the multiple panes and just how far apart they are. Dottie was running the spacewalk “choreography” from the Flight Deck. Clay and Rick were outside and Dottie was quarterbacking the show.

Nikon D3s, ISO 400, 1/1000, f/2.8

Even with those multiple thick frames, it was possible to get some decent shots. Here’s one of Rick working at night in the payload bay just outside the aft flightdeck. This clean shot was also made possible by good low-light sensors…his helmet lights providing the main light source.

Nikon D3s, ISO 3200, 1/125, f/2.8

Here’s another one. This was taken from the Cupola looking aft along the Russian segment. Those are two Soyuz ships docked to their docking compartments. It might appear inverted to you, but there isn’t really an up or down in space. This was the orientation you ended up in when you went headfirst into the Cupola.

Nikon D3s, ISO 200, 1/1000, f/8

And this one is the view from the Commander’s seat on the shuttle Flight Deck. Cool place to eat breakfast every morning, huh? See the guys working outside?

Nikon D3s, ISO 200, 1/1000, f/2.8

You’d think that with everything floating, it would be easy to stabilize a camera. That is true, but what was tough was stabilizing oneself and one’s subject. I can’t tell you how many times I missed a shot because I floated out of position, or my subject did. Foot loops are your friend. Imagine how tough it was to hold 13 bodies still for this shot. This is the complete combined STS-131/Exp 23 crew. The light shirts are my crew and the dark shirts are the ISS crew. Next to me in the front row is Dr. Oleg Kotov. Oleg is a Russian Cosmonaut (one of three onboard) and was the ISS Commander – a super guy and a lifelong friend. The crew of 13 represented the most people ever in space simultaneously. I doubt that record will be broken anytime soon.

Nikon D3s, ISO 200, 1/60, f2.8 – (4) SB-800 strobes

We always sent cameras outside with the guys during the EVAs (Extra-Vehicular Activity – NASA speak for space-walk). They were mostly stock D2Xs, but had some minor mods in order to deal with the rigors of functioning in a vacuum with several hundred degree thermal swings. They had a custom fit thermal blanket wrapped around them, a large viewfinder so that they can be used with the helmet, and a big button that could be pushed with those oven-mitt gloves to release the shutter. We turned them on before they went into the airlock and used Program mode, then hoped for the best. For the most part, the matrix did really well. Here are a couple of shots that the guys took with them.

Rick Mastracchio, EV1 – D2Xs, 28mm, ISO 200, 1/160, f/6.3

Discovery docked to ISS, 4/11/1010 – Nikon D2Xs, ISO 200, 1/125, f/5.6

Unfortunately, we eventually finished all of our work, and were running low on consumables, so we had to undock and come home. This shot was taken by Oleg during our departure. It’s hard to get a bad shot with this subject matter.

Nikon D3, ISO 200, 1/640, f/5

Finally, here’s a shot of Jim Dutton and I in our seats on the Flight Deck getting ready for an orbit adjust maneuver using the OMS engines. We were modifying our orbit to give us the best positioning and timing for multiple landing opportunities in Florida. This shot is a good example of the ability of a good TTL flash saving the day. The camera was apparently setup in Manual mode for outside imagery (probably my fault for not resetting it – we had a rule that one should always leave a camera in Program, ISO 200, AF-on for the next guy), and Dottie slapped a flash on it and took this frame. I’m fairly sure that I lost some vision after that stobe firing.

Nikon D3s, ISO 200, 1/1500, f5.6 w/flash

(Don’t ask me why those settings were used??)

Last thing. Building on years of Earth observation imaging, and Dr. Don Pettit’s work on imaging cities at night, we did some early work using the D3s to make time-lapse movies of an orbit from the ISS. Our efforts yielded some decent stuff, but nothing compared to what Mike Fossum and others have done since using the techniques that we pioneered. Make sure you check out their workhere.

Captain Poindexter’s Bio Can be Found Here

UPDATE

July 2, 2012 – Captain Poindexter died in a jet ski accident in Florida.

April, 2012

You May Also Enjoy...

VJ12 Contents

________________________________________________________ On Location: Africa - A Photo Safari in TanzaniaA workshop with Michael & Andy Biggs visits the Ngorongoro Crater, a Masai village, and the