I’ve decided to do this differently this year. Rather than going manufacturer by manufacturer, I’m going to look at some possible introductions, losses and trends over the next year, starting with the most likely and ending up with the “not gonna happen” department. The final installment of this series will be the MOST speculative, the things many of us are waiting for, but that either have little evidence either way or compelling reasons they might happen, balanced by equally compelling reasons they might not. This is all pure speculation – I don’t have any inside information. I read the same rumor sites many of you do, and I’ve been around the industry for a while as a photographer and a journalist. I have some knowledge of photographic technology, but I’m not an engineer. Take everything here with a grain of salt, and the stuff in the third installment with a teaspoonful.

Epson SureColor P9570 Update

Prior to getting into the predictions, I wanted to provide an update on our long-term test Epson SureColor P9570. First, and most importantly, it is producing images on a variety of media that I simply have not seen from ANY other color print process (inkjet or otherwise). The quality of these prints is the current reference for just how good color printing can look (and not just inkjet, but ANY color process). The P9570 lives in the shadows, just as the great black and white printmakers did. I haven’t seen any other color process that offers the depth and details in Zone I and Zone II that these prints do. The three kicker inks, the reason I arranged the P9570 review, are also providing unprecedented color gamut. I’m getting prints that are the equal of any Canon (or UltraChrome PRO-10) in the blues, and as good as orange/green kicker Epsons in the greens and warm tones – in the same print. I will go so far as to say that I will no longer print exhibition prints using any process OTHER than UltraChrome PRO-12. With anything else that I am aware of, there’s always the question of how much better the print could have looked. I don’t have the lab to test archival qualities myself, but the ratings from Wilhelm Imaging Research are better than any non-inkjet color process in history, and in the range with the best of other inkjet processes.

That said, the head strike concerns raised by people in the LuLa forums are real. I’m losing prints to scraping, and I’m working very closely with Epson on best practices to avoid it. I am confident that, as I learn the ins and outs of the printer, my success rate will improve. This is not a “throw a roll of anything in and print” printer. It is a printer that requires quite a bit of experimentation with media settings, matching of images and media (ink density seems to be closely related to the scraping issues), and even how we treat media on the roll. For years, we’ve been used to printers that have three settings – profile, matte vs. photo black, and MAYBE platen gap. This one has closer to fifteen settings, and their interplay is complex. In the first three weeks, I’ve made quite a number of absolutely stunning prints, but I’ve also lost quite a few to some setting not being right.

How much media would you waste at first learning dye-transfer or carbon-pigment printing? Almost certainly an enormous amount. I remember learning to print in the darkroom, and losing over 90% of the prints I made. My photography teacher threw me in the deep end – she had us printing on fiber-base paper from the beginning. No “try this nice Polycontrast Rapid RC first – it’s hard to screw up”. With three weeks and about five rolls of media through the P9570, I’m making a fine print about 70% of the time (and I AM making fine prints – these are gallery-grade images), and losing the image to some setting about 30% of the time. The P9570 is nowhere near as bad as learning curves in the darkroom, but it IS a new tool with new techniques to learn.

There is one particular image that I have been struggling to make a print from for weeks, because it has a deep shadow running the length of the print. The high ink density in that shadow causes quite a few papers to wrinkle just enough to cause head rubbing. Last night, I tried a vertical composition of the same image – it printed beautifully, because the problematic shadow was rotated 90 degrees (and was just a bit smaller). Today, I tried the horizontal composition on Epson’s Legacy Baryta II, a slightly thinner paper (so the suction will keep it from wrinkling) that can take a high ink density. The reward was a stunning fine print. There is definitely an art and a craft to this. One of the foci of the P9570 series going forward will be learning and teaching that craft.

Is it worth it? Unequivocally, yes! Without being able to display the prints on the web, I can’t do justice to the results I’m getting. A picture of a print at 1000 pixels across in sRGB doesn’t convey the impact of the 40×60” original brought to the print profile from ProPhoto RGB. A printing practice using the SureColor P9570 (or its little brother the P7570) is a commitment somewhat equivalent to a significant home darkroom, but it is producing incredible results that have increased my expectations of what is possible in color.

For less of a commitment in time and money, don’t forget the smaller SureColor P900. Its UltraChrome PRO-10 inkset is about 80% or 90% as capable as UltraChrome PRO-12, but it sits on a decent-sized table instead of wanting a decent-sized room as a print studio. It isn’t as versatile, because it’s fundamentally a 17×22” sheet-fed printer instead of a roll-fed monster that will take pretty much any roll you can lift. It’s essentially the same inks, minus the orange and green that are so special in warm tones and deep forests. While the feed on the P900 is less versatile, it’s also less picky. There aren’t the huge number of settings to adjust, and my success rate is significantly higher. Of course, the success rate on a 17” print is always going to be higher because there isn’t the huge area for something to go wrong. I would love to see a full-on UltraChrome PRO-12 printer that is less complex than the giant P9570, and I’ve told Epson so. It would also be less capable – I don’t think we’re going to see 44” roll feed without the size and the settings – but a 17” or 24” printer that used these inks could be less complex.

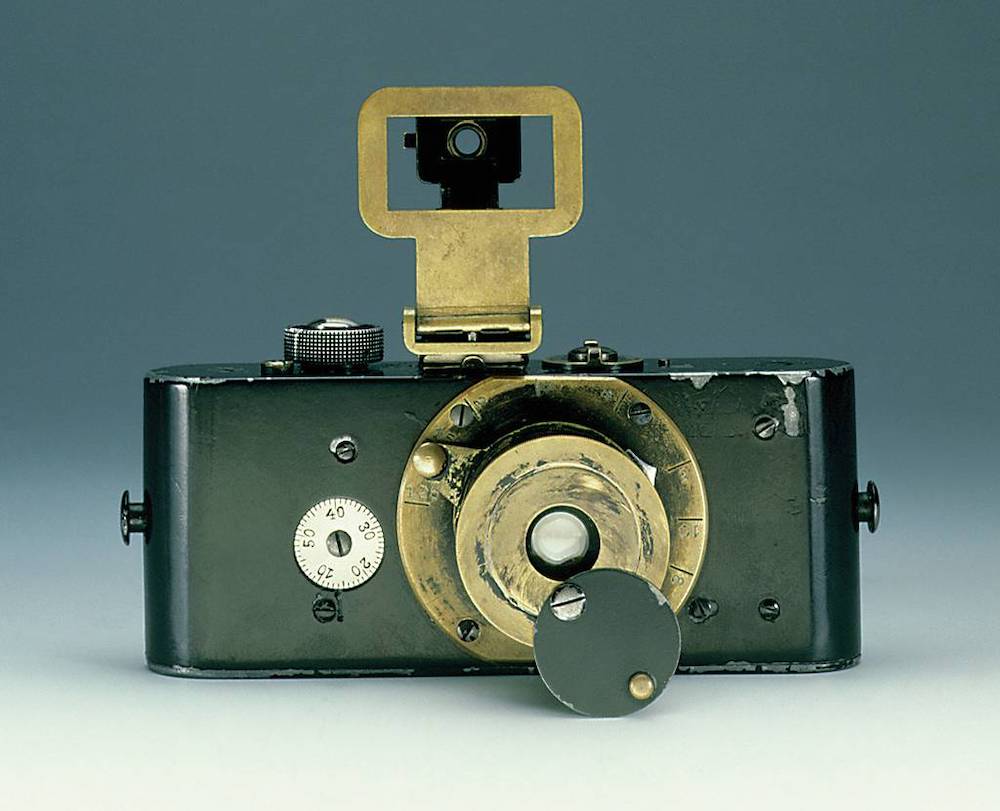

In many ways, a sheet-fed printer is much less complex than its roll-fed relatives, but there is a real issue with paper availability. Ever since 1913, when Oskar Barnack chose to build the Ur-Leica with a 24x36mm frame size (we call it full-frame today), a lot of photos have been taken on cameras with a long, skinny 1.5:1 aspect ratio. By the time of the Leica M3 in 1954 and the Nikon F in 1959, there was very little question that 24x36mm was here to stay, and that most photos would be taken with a 1.5:1 aspect ratio.

Photographic paper, however, has always been manufactured to a different set of sizes that fit the squarer aspect ratios of medium and large format cameras. 8×10”, 16×20” and 24×30” are all exact aspect ratio matches for 4×5” negatives, but awkward fits for the longer, skinnier 35mm standard. 5×7”, 11×14” and 17×22” are not exact, but are close fits for 4×5” and most other common image sizes, which are generally close to either a 4:3 or 4:5 aspect ratio (much squarer than 35mm). Other than 35mm and cinema frames, the few film frames not based on 4:3 or 4:5 are even squarer (6×7 cm is almost square, while 6×6 cm IS square).

Even after 110 years, the paper manufacturers STILL haven’t figured out that 35mm is a popular size – and that the two most common digital sensor sizes both use a 1.5:1 aspect ratio. Aesthetically, my opinion is that the paper manufacturers might well be right – I really love my GFX 100s’s squarer 33x44mm sensor – but the skinny frame is here to stay, and the paper makers should start accommodating it! Only a few of today’s common paper sizes make any sense with the skinny frame. 4×6” is an exact match, and small prints like that are likely to be borderless, so an exact size makes sense. 13×19” is excellent, because you’ll probably want a border on a larger print and it fits a 12×18” image very well. There is no good paper size for an 8×12” image – the ideal would probably be 9×13”, which doesn’t exist at B&H, but see below for a source. The best bet is 13×19” to the rescue again – print two images to the sheet. The last obvious size in the series would be the useful 17×25” – but it’s very rare (B&H lists only four papers, two from Inkpress and two from Moab, two of which are out of stock). The result is that 16×24” images are almost impossible to print on most 17” printers, even though the printer is big enough to handle this popular size. A roll adapter solves the problem since 17” roll paper is easily available, but only Epson’s P5000 is really designed to handle 17” rolls. The smaller P900 offers a roll adapter, but no cutter, while the Canon Pro-1000 won’t accept rolls at all. At least Epson and Canon themselves might want to start cutting paper to 17×25”?

It is well worth noting that Red River Paper, a direct seller of photo and art papers they source from various mills under their own brand, has a nice selection of papers in both 9×13” and 17×25”, along with other unusual sizes like 13×38” panoramic and 12×12” square. They will also custom cut papers for a reasonable fee, but only from sheets (their largest sheet is 17×25”, so no luck in getting large, odd sizes like 17×50” panoramic, a useful size in 17” sheet fed printers).

What’s coming this year

The current state of lenses

One important development in lenses is the introduction of lines where ALL the lenses are excellent. Nikon guru Thom Hogan recently wrote that he has used all of Nikon’s S-line lenses for the Z-mount and he finds them all to be very good or better. His Recommended rating is tough to get, and even the weakest of the S-line lenses (the 14-30mm f4) gets a conditional recommendation and a note that it is “one of the three-lens set that those travelling with Z’s probably should adopt”. He considers every other S-line lens better than that, and calls the relatively inexpensive 50mm f1.8 very near a Zeiss Otus in capability (with the 50mm f1.2 going well beyond the Otus). I’ve used a bunch of the S-line lenses (not nearly all of them), and I agree with him. I haven’t seen ONE I don’t like, and one of the things I like about the Z system is the guarantee of good lenses. I’d pick up any S-line lens without worrying about it.

Thom Hogan’s comment got me thinking: what OTHER lens lines are like that? The first one that came to mind is Fujifilm GFX. I’ve used four of the lenses (32-64mm, 120mm Macro and 20-35mm extensively and 23mm a bit). I like everything I’ve used a LOT, and I’m very happy with a 20-35, 32-64, 120 Macro set (I’m going to be very sad to see a couple of loaners go back – I’ve had the 120mm a long time). The lens I’m looking for next is something longer, probably something not released yet – although I’m also very excited about the upcoming tilt-shift lenses.

There are several other all very good or better lines. Quite a few Sigma Art lenses have passed through here, and I’ve liked every one I’ve had a chance to use. I’ve liked pretty much every recent Sigma I’ve tried, in fact – although Contemporary lenses are often very strong value for money and very compact, rather than superb high-end lenses (Sigma succeeded in their design philosophy – they have the Art line for their all-out efforts). I wouldn’t hesitate to use any of Sigma’s Global Vision lenses for many things, and I’d use any Art lens I’m aware of for anything. I’d love to see Sigma introduce some long Art telephotos.

The same seems to be true of Sony G-Masters. Those I’ve used tend to be excellent. Again, I haven’t tried the whole line, but I’ve used enough G-Masters to be very confident that if I pick up an unfamiliar Sony lens, and it has that little orange badge on the side, I’m probably going to like it a lot. This is especially true of RECENT G-Masters, because Sony has been in the mirrorless lens business long enough that they’re updating quite a few of their older lenses.

One thing that makes Sony lenses more confusing than some others is that they have no less than three different “high-quality” badges (plus unbadged value lenses). G-Master is undoubtedly the best, ranging from very good to world-class, while G is generally an indicator of good lenses with some of them better than that. The 200-600mm f5.6-6.3 G is a very good to excellent lens and a stunning value, while the 24-105mm f4 G is a good to very good lens at a fair price. In the very good to excellent range, there is quite a bit of overlap between the apparent meanings of G and G-Master (why is the 100-400mm a G-Master, while the 200-600mm is a mere G and at least as good a lens)? Oddly, a Zeiss badge on a Sony lens (as opposed to a lens made and sold through Zeiss themselves) mostly means “old lens” these days. Some of them are very good or better, some of them are mediocre, most of them will eventually be replaced by a G or G-Master.

Red badge X-series Fujinon lenses are similar – not a dud in the bunch, and some real stunners. Fujifilm does us another favor and clearly differentiates their real value lenses from everything else. The red badge means excellent lenses, while Fujinon XF without a badge means at least a good lens, generally very good, sometimes excellent. The lenses that are merely good tend to be older designs – Fujifilm, like Sony, has been in the mirrorless business for a long time, and some lenses that are merely good on 26 and 40 MP sensors were better than that on the cameras they were designed for. The real value lenses are designated Fujinon XC, and I haven’t used any of them, but reviews indicate that they are like most other value lenses – a mixed bag optically, with designs meant to be compact and inexpensive.

There are two badges I haven’t really used any lenses that carry, and one of them is important. The big one is Canon L. I haven’t been able to lay my hands on any Canon mirrorless review gear at all, so I have no personal opinion of L lenses. Their reputation is excellent – every bit the equal of S-Line, G-Master, Art or Fujifilm’s red badge. As a matter of fact, it was Canon who started the practice of badging their best, and the L badge and the distinctive red ring is the only one of the current badges that goes back to the DSLR days. Nikon’s ED gold ring has been replaced by S-Line as ED glass spreads to more and more lenses. The other badge I haven’t used is Tokina Opera.

OM System’s PRO designation is an odd one, because its meaning is slightly different. It means “incredibly well built lens that is much better than any sensor you might possibly use it on”. I’ve used several of them, I’m very impressed with their mechanical construction and their weather sealing. I can’t say much about image quality (which may be anything from very good or even merely good to world-class), because any lens better than very good is wasted on the Same Old Sensor. I’ve never found much fault with an OM PRO lens, but I’ve never been terribly inspired by one because they all go with 20 MP sensors with limited dynamic range. Any lens with any of the other badges would be able to look really good in the center, and that’s all that a Micro 4/3 sensor is picking up. OM PROs do too, but there’s no way to know if they’re better than that, because the Same Old Sensor is holding them back.

Expected Lens Updates

Updating old lenses is mostly a Fujifilm and Sony project, since their mirrorless lineups are old enough to have quite a few older lenses in them. Sony just introduced one of the most important updated lenses they needed – the 20-70mm f4. It’s in the “almost an update, but with something new” category, since it has an extra 4mm at the wide end. I haven’t seen one in the flesh, but early reviews are very promising (and I’ve been complaining about Sony midrange zooms other than the GM series for years, so I’m very glad to see it).

Both Canon and Nikon have mostly very fresh lenses, and are still filling holes rather than replacing lenses. Sigma is constantly updating stretched DSLR lenses by replacing them with real mirrorless designs. Expect these trends to continue. Many of the Fujifilm and Sony updates are hard to identify as such – both companies will sometimes introduce a updated lens with a clear II in the name, discontinuing the older lens in the process. Both also like to introduce lenses with similar but not identical top-line specs, sometimes leaving the older model in the lineup as well (see: Sony 50-55mm lenses). It can be confusing which lens is the new one, and which lens is the better performer can also be confusing, because some of the near-update lenses are cost-cut versions.

The wild card is Canon – there are four brand-new and incredibly expensive RF lenses that are actually due for an update in the next couple of years. Those are the four EF-to-RF supertelephotos, all introduced in the past year, but actually just existing (and, to be fair, absolutely superb) EF lenses with permanent mount adapters. The 800mm and 1200mm are also the 400mm and 600mm with permanent 2x teleconverters. The Canon lenses are highly comparable to the Sony versions released at around the same time we first saw the Canon lenses in EF mount – spectacular lenses, but missing a few things seen on the brand-new Nikkors (which are new designs), primarily the built-in teleconverters.

If Canon releases integrated-TC versions with updated optics (which they have patents for), expect screams from people who spent $10,000+ on the EF-to-RF lenses. If they don’t, expect gloating from Nikon users. The best thing Canon could do? Offer an EF to RF mount conversion service at a reasonable price ($1000 or so?) for owners of the EF version. For owners of the RF version? Offer a conversion service ($2000?) for these 400mm lenses to 800mm and 600mm lenses to 1200mm if new 400mm and 600mm lenses appear. The longer lenses are simply the shorter ones plus a permanent teleconverter (it’s not Canon’s standard removable teleconverter, but one optimized for these two lenses). It would encourage people to buy a new native RF 400mm or 600mm if they knew their EF-to-RF lens had a new life at a longer focal length…

Full-frame camera updates

After seeing only two updates to full-frame cameras this past year, and NO truly new models, we are expecting quite a few in 2023. Nikon didn’t introduce any full-framers at all in the past year, and there are five possibilities for the coming year (we won’t get them all, but we’ll see some). Two of them are new models and fit in other categories, so we’ll discuss the three update possibilities here. Sony and Canon have a couple of models each that could use an update, and Panasonic also has a couple of possibilities if they keep pursuing L-mount.

Nikon is as certain as certain gets in this business, and they could update any or all of the Z5, Z6 II and Z7 II. They may have to update the Z5, because I’d be a little surprised if the front-side illuminated 24 MP sensor it uses remains in production much longer. It’s probably a variation on a Sony sensor that has been around for well over a decade in one form or another – since the Sony a900 and Nikon D3x in the late 2000s. Most modern 24 MP full-framers use the back-side illuminated (BSI) successor model. If they update the Z5, what sensor would they put in it? One logical possibility is a 24 MP BSI Sony sensor, possibly with some secret Nikon sauce on it – but that sounds an awful lot like the existing Z6 II. Another possibility, which moves the resolution needle, is something related to the 33 MP BSI full-frame sensor in the Sony A7 IV. That’s a relatively slow sensor, maybe not fast enough for the video-heavy Z6 III, but perfect for a major update to the Z5. In either case, they’d need to find something else for the Z6 III.

The most exciting sensor possibility for the Z6 III is something stacked – either 24 MP or 33 MP. That would make the Z6 III a notably fast camera, well ahead of its peers in the $2000-$2500 range (it would almost certainly move towards $2500 or more if it had a stacked sensor). It probably wouldn’t get the full “baby Z9” treatment due to cost, but it would still be the fastest mid-priced full-frame camera. The other possibility is something like the A7 IV sensor with a modest resolution improvement, but not stacked – but it would have to be fast enough not to backslide on capabilities the Z6 II already has.

The Z7 III also faces a sensor challenge. It would take a LOT of non-sensor improvements for Nikon fans to be content with a fourth camera based on the D850 sensor – even though it’s still one of the best full-frame sensors ever made. The most logical update is to a “Nikonized” version of the 61 MP standard pixel sensor introduced in the A7R IV – one with ISO 64, Nikon’s color filtration and possibly a small (and probably accidental) resolution bump. The only reason I don’t think this is a slam dunk is because it didn’t show up in the Z7 II. The A7R IV was well over a year old when the Z7 II came out – plenty of time to Nikonize that sensor (although somewhat shorter than the spacing between the A7r II and the Nikonized version of the A7R II sensor arriving in the D850).

A bigger update would be to a new sensor in the 80-100 MP range – but if Sony has one of those to sell, why isn’t it in the A7R V? Sony supplies most of Nikon’s sensors. Yes, Sony Semiconductor does sometimes sell a sensor before Sony Imaging uses it (the 26 MP and 40 MP APS-C sensors that would benefit Sony going to Fujifilm first are examples) – but they have been ignoring their APS-C line. It would seem much less likely that they’d sell a sensor that would be a great upgrade to one of their most prestigious cameras, especially when they’ve just upgraded that camera without changing the sensor. We’re now two years from another A7R upgrade, and Sony is unlikely to let Nikon grab the resolution crown for that long with a Sony sensor. More on high-resolution cameras in a coming installment, but that’s why I think a very high-resolution Z7 III is far from certain. The last possibility is a “baby Z9” with a stacked sensor (probably the Z9 sensor, maybe with a slightly slowed-down processor), but people have been calling that a “Z8”. Maybe Nikon defies expectations and calls it a Z7 III?

Canon’s two best upgrade candidates are both at the low end of their line – the EOS R and EOS RP. They pretty much have to fix the low end in 2023, or else abandon it. Neither the EOS R nor the EOS RP is competitive in today’s market, and they don’t handle like Canons. The easiest thing for them to do would be to take the EOS R6 sensor, which is lower resolution than the EOS R and EOS RP sensors, but outperforms them in other ways, and throw it in a stripped down body with relatively standard Canon controls. Both the EOS R and EOS RP use weird controls seen on no other Canon, and one priority has to be to get the low end working like the rest of the line. They might make one camera to replace both the R and RP, or they might do two models. If they do two, will the lower end one be viewfinderless? If they do two, the R6 sensor might end up in the lower model, and the higher end camera might get an updated version of the 30 MP EOS R sensor?

The only other possible real upgrade (as opposed to a new model) in Canon full-frame is an EOS R5II – that’s not anywhere near as urgent, since that camera is much newer than the low-end models, much more competitive and a quintessential Canon with excellent handling. It might use an upgraded version of the EOS R5 sensor, or a ~60 MP sensor, or an 80-100 MP sensor (or are they saving THAT for the EOS-R1?). If it is going to remain a still/video hybrid, the other crucial upgrade is upgraded cooling (or lower heat production). It could also become a pure pixel monster (with a resolution upgrade), and leave the hybrid game to the R6 II, R3 and R1 (in this scenario, the R1 is a superfast 45-50 MP camera).

Sony has a lot of possible upgrade candidates, but the core of their line is recent and in good shape. The A7 IV is a little over a year old and the A7R V is only a couple of months old. The A7 IV was a major upgrade to the venerable A7 III. The four cameras they could possibly update, in order from oldest to newest, are the A9 II, A7S III, A7 C and A1. The A1 is only approaching its second birthday, meaning an upgrade to that camera is more likely toward the end of the year or in early 2024. It will probably be the first of the “Olympic cameras” released in time for the Paris games in 2024. Since it’s several months older than the Nikon Z9 or Canon EOS-R3, it is the only one of the three with a significant chance of sneaking into late 2023.

The most likely upgrade I can see to the A7S III and A9 II merges the two. Fast cameras tend to be good video cameras, and good video cameras tend to be fast. The big loss on merging the two is, of course, the native 4K resolution of the A7S III. Anything that is 4K native is, by definition, a 12 MP camera, and still photographers aren’t going to count that as a hybrid (even though 12 MP is fine for many uses of still photos – anything online plus low-resolution printing like newspapers). What Sony COULD do is offer a 24 MP camera that shoots 4K full-width at an exact 1.5x oversample for very high quality and also does 6K open-gate. If it’s very fast with a stacked sensor, it’s a direct upgrade to the A9 II, and it could potentially be a better video camera than the A7S III. The very fast stacked sensor could also enable some very, very fast 4K slo-mo, especially in a 1.5x crop mode.

The question about the A7C is “what do you take out of it”. The original A7C is basically a smaller A7 III with a lousy viewfinder, but it came out when the A7 III was already two and a half years old. If Sony simply throws the year-old A7 IV in the A7C body and sells it for an A7C price, anyone opting for an A7 IV had better really like nice viewfinders. I’d almost think it’s more likely that the A7C retains its A7 III roots and moves downmarket. Sony often has a full-frame model at or just above $1000, but it’s generally an older camera. What if the A7C II was made to sell in that price range? Alternatively, what if the A7C II gets a better viewfinder (maybe the best of the APS-C finder setups – the original A7C actually has a finder related to the one in the RX100 compacts) and at least most of the guts of the A7 IV, but gets a price increase to the $2000-$2200 range? The original A7C remains in the line as a $1000 camera…

If Sony were to update the A1, they have two choices. One is a modest upgrade – even faster AF, 30 fps without lossy compression, the newest 2,100,000 dot rear screen, a few more video modes, etc. The second is that they didn’t use a super-high resolution sensor in the A7R V because it comes in a stacked version, and they’re saving it for the A1 II… Let Nikon use the non-stacked one in a Z7 III, then release the stacked sensor a few months later? Sony occasionally introduces “how did they do THAT???” cameras, and a super-high resolution A1 II would be one of those. They don’t always fully meet their spec sheet when the spec sheet is jaw-dropping, but they tend to do a lot anyway.

Panasonic has a couple of relatively easy potential updates, as well as a bigger, but potentially very important job. They just updated the S5 with a significant midlife kicker – finally adding the phase detection autofocus every other camera maker has been using for years, as well as a clever fan-cooling system (yet another video-centric feature that reinforces their market niche).The most prominent easy update is an S5R – put a high-resolution sensor in the successful S5 body. The S5R absolutely needs the phase-detect AF the S5 II just got. The S5 II is a well-specced upper midrange camera, perhaps with a little video boost over what’s expected in that range (especially with the S5 IIX version).

The bigger job is the successor to the S1H. The S5 pretty much succeeded the S1, and the S5R would be a successor to the S1R, but the S1H needs a successor, and a more “normal-sized” body and phase detection alone won’t be enough for Panasonic’s video-centric flagship. It almost certainly needs a stacked sensor in order to do the video modes it should have. Does it need to do 8K? I’m not actually sure it does, although it wouldn’t hurt. It needs to keep Panasonic’s unique video toolset, of course – and its video modes and quality need to be market leading, if not market defining. I’m not sure it should even be in a still-camera body – this is a video camera, and it needs to be optimized for its job. Will Panasonic release this camera? The answer is a clear “maybe”…

New APS-C cameras

The usual suspects, and the one company I’m nearly sure about, are Fujifilm. I’d be shocked if we didn’t see at least one new 40 MP APS-C camera from them this year. The most logical suspects to get the new sensor are the X-S10, the X-Pro 3 or both… We have a good idea of what either camera would be like since Fujifilm is small enough that not only the sensor but the processor and much of the firmware tends to get carried over between models, and they don’t tend to mess with controls within a line very much. Both of them would inherit a lot of X-T5 DNA in a different body type (neither would get the extra video features the X-H2 inherits from the X-H2S). There are a couple of questions… Would an X-Pro 4 get image stabilization? What would its rear screen be like (if any?!?)? 40 MP versions of either the X-E4 or X-T30 seem more likely to be 2024 cameras.

The other Fujifilm APS-C question is whether we’ll see any body besides the X-H2S with the stacked sensor? The logical one might be the X-S10, but can that tiny body handle the heat? Alternatively, what about an all-new body with the stacked sensor? If it’s a real dedicated video camera, why not some sort of a camcorderish body? I’ve often wondered why the GH cameras and the A7S series insist on looking like still cameras. That’s not the best body style for a video camera, and those aren’t really still cameras! Probably 95% on some new Fujifilm APS-C camera, 80% on at least one that’s either 40 MP or stacked, 50% on at least one of each?

Anybody outside of Fujifilm could release an APS-C camera, and nobody’s guaranteed to. Nikon is the most likely (maybe 75%), and will probably go high, coming in on top of their three (or is it one) existing models with a camera that appeals to D7x00 users and maybe even D500 users. Either of Sony’s new APS-C sensors, the 26 MP stacked sensor or the 40 MP BSI sensor, could be perfect – assuming that neither one is a Fujifilm exclusive. The next logical model numbers are both important ones for Nikon – Z70 harkens back to the original D70, and to the whole line of D7x00 DSLRs – some of the most important products in Nikon’s digital history. They need to release a Z70, and they need to get it right.

The Z90 designation is, if anything, even more fraught. It goes back to the famous D90, but before that, it goes back to the N90 and N90s (F90 and F90x in some countries). It also emphasizes the relationship to the Z9. Not only a famous old digital SLR, but two of their most beloved autofocus film SLRs, use the number 90. Will Nikon release a Z70 and/or a Z90, and will they live up to their illustrious forebears? If they do both, the Z70 may very well be 40 MP, with the Z90 using the (more expensive) 26 MP stacked sensor and having superb high speed and video capability. They could either use exactly the same (new, hopefully weather sealed) body, or two bodies, with the Z90 somewhat larger to cool the power hungry stacked sensor. Will Nikon make the lenses those cameras deserve? Please, Nikon, give us in-body image stabilization – those bodies would be perfect for the f1.8 full-frame primes – how about the 50mm as a portrait lens? A stacked Z90, especially in a rugged body, could also be called the Z500 (to evoke the D500), or even the Z100 after the original D100 and more importantly the F100.

Canon will probably go low (80% chance of anything, mostly something below the R10 or between the R7 and R10). The EOS R7 is already a high-end APS-C camera, and there is space below the EOS R10. The other potential space is between the R7 and R10, where there’s a significant gap. What they really need is lenses – toss the EF-M designs in the trash can and set some of your better lens designers to work on APS-C. This problem isn’t unique to Canon – nobody but (arguably) Fujifilm has a full, modern line of APS-C lenses, and even they have a few “oldies” dotted in there – lenses designed for 16 MP sensors that underperform on bodies that now go up to 40 MP.

Canon, however, has it worse than most – they don’t have the long history of APS-C lenses that Sony does, with a lot of duds, but also some nice glass. The few lenses they have aren’t as good as the few DX Nikkors. Nikon’s APS-C lenses are quite surprising, given their prices and specs – and Canon’s aren’t. Nikon also has some excellent, compact full-frame lenses that make a lot of sense on APS-C (although image stabilization is a major issue – Nikon’s full-frame lenses expect it in the body, and their DX bodies expect it in the lens!). Unlike Sony, Canon won’t let Sigma bail them out. Sony’s midrange zooms for APS-C are nothing special (except for the expensive 16-55mm f2.8 G), but Sigma comes to the rescue with the reasonably priced 18-50mm f2.8 Contemporary, although it wants an image-stabilized body, and most Sonys aren’t.

Sony could do anything, or nothing – I’d give them a 50/50 chance of doing anything at all. They have two (actually three – they haven’t even used the 26 MP BSI sensor in a still camera) great sensors that they’re making for Fujifilm (it’s not 100% confirmed, but I’d be shocked if Fujifilm’s new sensors were anything BUT a pair of Sonys). They could release a baby A1 using the 26 MP stacked sensor, a real successor to the long-gone NEX-7 with the 40 MP sensor, or both. If they want to do anything with APS-C going forward, they need to replace essentially all of the existing cameras – every one of them is a derivative of the A6000, and the A6000 is approaching its 9th birthday in February.

There are three models currently in stock at B&H (excluding the viewfinderless, vlogger-only ZV-E10, and all in a variety of kits). Only one of them is Image stabilized – the $1350 A6600. The A6600 is a capable camera, but it’s asking a lot of money for a 2019 camera with a 2016 sensor in a 2014 body with the durability of a $600 camera. Fujifilm’s similar X-S10 (with a newer sensor and better controls) is $999, while both Fujifilm and Canon will sell you a much more modern camera with a significantly higher resolution sensor in a rugged weather sealed body with excellent controls for only a few hundred dollars more (EOS-R7 for $1499 and X-T5 for $1699).

What would it be like if you walked into an Apple Store today, and every iPhone you could buy was a version of the iPhone 6? What if the two of the three available iPhones shared the worst battery on the market with the iPhone 6? The A6000, discontinued only this month and the basis for Sony’s entire current APS-C lineup, is slightly OLDER than the iPhone 6. What if they had significant improvements in one area, but a lot of hand-me-down features in others? Most of us would buy Android!. The A6100, A6400 and A6600 have significant AF improvements over the ancient A6000, but they share three important negative features.

The first (not shared by the expensive A6600) is the aforementioned terrible battery – the NP-FW50 was first introduced in 2010, and it was made to fit in the NEX-3 and NEX-5, the first mirrorless cameras Sony ever made. The early NEXs were TINY – under 10 oz/300 grams – viewfinderless cameras, and the miniscule battery was one of the ways they got so small. Sony has a MUCH better battery – the NP-FZ100 is used in the full-frame cameras and the A6600. The second hand-me-down feature is a terrible user interface – the first control dial is a nice one, positioned on the rear shoulder of the camera for the right thumb – but the second control dial is a loose ring around the four-way controller, ALSO operated by the right thumb, and both the third dial/exposure compensation dial and the AF joystick are missing altogether. The third hand-me-down feature is the A6000’s sensor. All three of these cameras use the same non-BSI 24 MP sensor that goes back at least to the A6300 (including the exact number of phase-detect points), and much of the design (minus the phase-detect AF points) may actually go all the way back to 2011’s NEX-7 – if it doesn’t, it’s a close relative.

There are actually at least three APS-C cameras that Sony could make relatively easily and with decent model differentiation, corresponding to their three modern APS-C sensors. If they used one body (please make it a new body, NOT the A6000 body), one camera per sensor seems right. It wouldn’t be a big deal for them to design a body with a front dial, a joystick and a good viewfinder (they make viewfinders, after all). If they were willing to use two bodies, they could easily get a fourth camera out of their three sensors – a very compact low-end ($650?) model using the 26 MP BSI sensor along with a midrange ($1000) body using the same sensor with a somewhat larger body with more controls and image stabilization. There would be two higher-end options ($1500 and $2000?) in the bigger body (the less expensive one 40 MP, and the top model using the stacked sensor). The smaller, cheaper body might sell very well. These are all pretty much “parts bin projects” for Sony, and they could use them to grab a very clear second place in APS-C within six months. Fujifilm would still have a slightly broader line and more consistent lenses, but Sony’s line would leave Nikon (three cameras, but little differentiation –nice lower-end lenses, but VERY limited choice) and Canon (two well-differentiated cameras, but only two lousy lenses) well behind.

Of course, Sony’s other option is to introduce a full-frame camera under $1000 and leave APS-C behind (either getting out of the market or leaving the current models on the market). I think that’s as likely as anything – but I also think that a few better APS-C cameras are relatively likely, since they are a low effort project.

Computers and Software

Apple Silicon is here to stay, and the Mac Pro may not be. Apple continues to convert their Mac line over to their own processors – they started with their lower end models a couple of years ago, converted the 14” and 16” MacBook Pros to the M1 Pro and M1 Max at the end of 2021 and introduced the incredibly powerful Mac Studio earlier in 2022. The MacBook Pros have just received an update to the M2 Pro and M2 Max chips which are modestly faster than the current M1 Pro and M1 Max chips, and they have a couple of extra cores. Unfortunately, the two additional cores are efficiency cores, which high-throughput applications like raw converters barely use (but which will improve the responsiveness of e-mail and web browsing while you wait for that big batch conversion). The bigger news is the GPU, which is much faster if your applications use it, and the fact that the M2 Max supports a 3x memory configuration for a maximum of 96 GB. The M2 Pro is still limited to 32 GB, suggesting an M2 Max with either 64 or 96 GB for RAM-intensive work on very large files.

As of December, 2022, there is a rumor that the M2 Extreme has been canceled – this was the hypothetical top-end chip for the Mac Pro. The current top of the line is the M1 Ultra (a double M1 Max) in the Mac Studio. An M2 Ultra is likely to be a 24 core chip with 16 performance cores and 8 efficiency cores (since the M1 Ultra was exactly a double M1 Max, it’s reasonable to expect the M2 might be as well). 76 trombones graphics cores will provide GPU performance on par with very high-end GPUs, while RAM configurations should include 64, 128 and 192 GB. An Extreme was supposed to be a double Ultra (if you’re counting, 32 performance cores plus 16 efficiency cores or 16 iPhones worth of performance cores). If there’s no Extreme coming, what will the difference between a Mac Studio and a Mac Pro be? Even the Mac Studio is typical Apple in having no internal expansion. The Mac Pro very likely would have some – but what?

Standard NVMe SSD slots are a reasonable possibility – but not worth very much. An Ultra-powered Mac Studio already has six Thunderbolt 4 ports (all on separate buses) and 10 Gb Ethernet – plenty of places to hang FAR more storage than could ever fit inside, and at up to the same speed as internal drives. PCIe slots could also work – but probably couldn’t accept GPUs given the way Apple Silicon graphics are designed. Not much use for photography, although there are applications in audio and video work. Any card that would work in the internal slots should also work in an external card cage connected via Thunderbolt, and they aren’t terribly expensive (a few hundred to a thousand dollars, much less than the specialized A/V interfaces that are their most likely use). PCIe slots are useful, but niche.

The two most important expansion possibilities seem to be architecturally unlikely with Apple Silicon – RAM and graphics. For the type of work most LuLa readers do (less so for games) , the internal GPU in a M1 Max or M1 Ultra Mac is already as fast as a big, expensive gaming GPU – but the price is that it can’t be replaced or expanded. Both RAM and GPU are hardwired in the Mac Studio and every other Apple Silicon Mac, and it would be a big departure from the Apple Silicon architecture if they AREN’T hardwired in the Mac Pro. The deeply integrated CPU, RAM and GPU are how Apple Silicon gets as fast as it is, but they also seem to preclude the two most useful forms of inside the case expansion. It’s likely to have the same RAM and graphics options as a M2 Ultra Mac Studio (probably 64 GB, 128 GB, 192 GB RAM options – although it wouldn’t be all that hard to offer 256 GB as well). There are a few users, mostly in high-end video and in science, who need much more than that, and it would be a major change to accommodate them. If a Mac Pro is just a Mac Studio with a card cage and a couple of SSD slots, it’s nothing special (and should be only modestly more expensive than a comparable Mac Studio). If it’s not, it’s a completely different kind of Mac, and it is likely to be very expensive because it has a lot of specialized hardware.

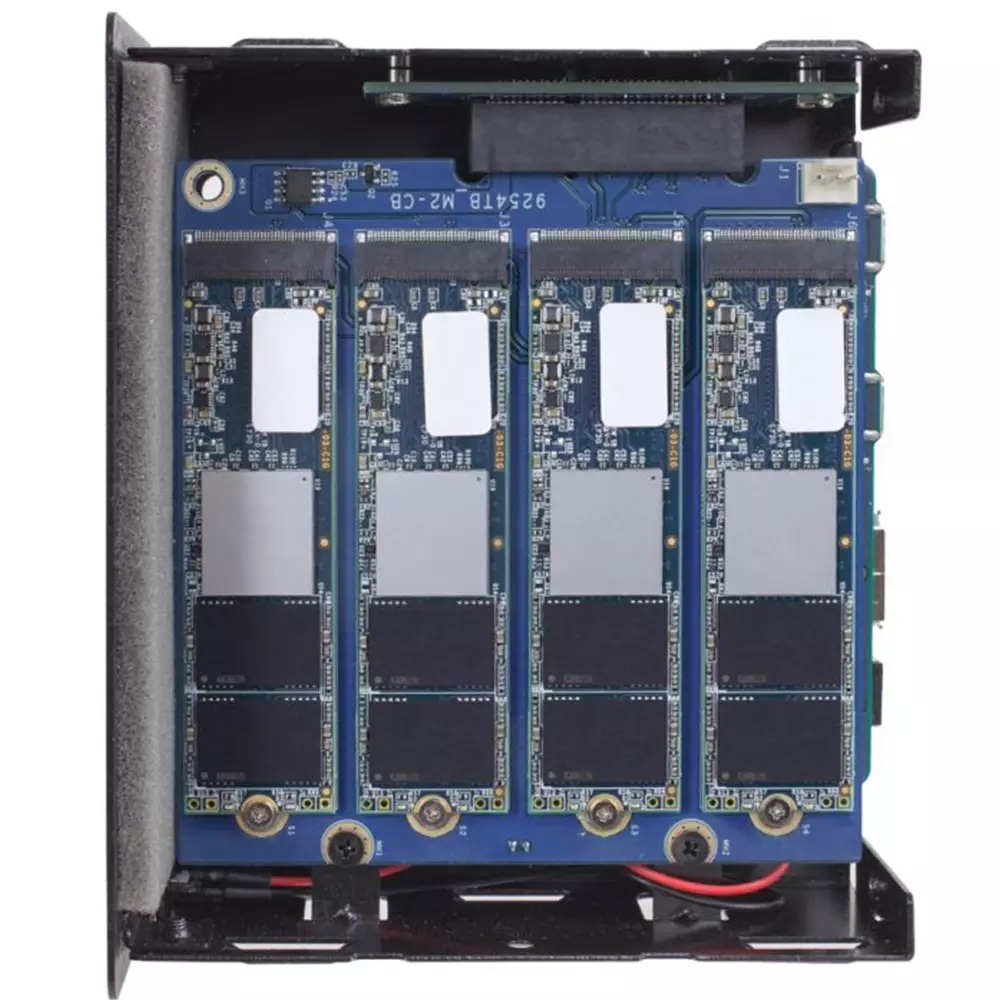

Most photographers won’t want the Mac Pro – if it’s not unique, the Mac Studio will serve us just as well, and we won’t want to pay for the PCI-E card cage we don’t need (the cost of the SSD slots is trivial, since you can get four of them in a Thunderbolt enclosure for $249 from OWC). If it IS unique with expandable RAM and GPUs, it’ll be outside of most photographers’ budgets. There are rumors of an iMac Pro – probably a Mac Studio attached to a very nice, but very glossy display. That will be a matter of taste for individual photographers. By the end of 2023, we should have two to three excellent choices from Apple – high-end MacBook Pros, the Mac Studio and perhaps an iMac Pro.

I just don’t know Windows well enough to predict what’s going to happen over there. Intel and AMD do seem to be making significantly faster processors again, after a multi-year lull. Windows 11 seems to be relatively stable, or at least complaints about it aren’t finding their way around the way they did about several previous versions. I like Apple hardware and software simply because it usually seems to just work. I’ve only had a couple of downright BAD Apple products in over 35 years with them (one of them is fairly recent – the infamous butterfly keyboard MacBook Pros). At any given time, probably a third of Windows hardware is downright bad – although there are lines, like ThinkPads, that reduce those chances.

Windows also gives up some stability in order to support two kinds of hardware. One of them is really cheap computers – Apple never has to consider that they might encounter a $100 laptop, while Microsoft does. The other is gaming rigs. Apple goes out of their way to NOT support intense gaming on the Mac, which means that they don’t have to allow stability-robbing sorts of system access demanded by games (and frequently exploited by malware). They also don’t have to consider hardware being run as close to the edge as gaming stuff often is. Photographers trying to get high performance out of Windows often have to use equipment designed, first and foremost, for gamers. If you buy a MacBook Pro or a Mac Studio, it’s designed for people working with photos, audio and video. Windows machines with that specific design are hard to find, and even the few companies that specialize in them (Puget Systems is an important one) have to use a lot of parts built for gaming.

A good photo workstation is the computer equivalent of a Mercedes – built to cruise for years at Autobahn speeds. A gaming rig is a Ferrari – somewhat faster and a lot touchier. Once you get above the Honda level of basic office machines on the Windows side, most of what you find are Ferraris. Apple builds a bunch of Hondas and a lot of Mercedes. Even the biggest, most firebreathing Macs tend to be 12-cylinder Mercedes – really fast and very smooth, but very expensive.

In software, I’m increasingly confident about the survival of Lightroom Classic. A few years ago, I gave it only about a 50/50 chance. This year, I give it 90/10 or better. I think Adobe may have gotten “New Coked”. For those who don’t know what happened with New Coke, it was a response to the Pepsi Challenge ads – Coca-Cola decided to change the taste of their flagship soda because Pepsi was running ads with survey results showing that people preferred Pepsi in blind taste tests. They put out a new, more Pepsi-like formulation and had to walk it back in less than three months as consumers didn’t like it. Adobe was behaving like they were going to shut down Lightroom Classic in a year or two back in 2020, then they started giving it meaningful upgrades again. My best guess is that they HAD decided to shut down Lightroom Classic a few years ago (or leave it in a state of suspended animation, getting new camera updates but not much else), but they weren’t seeing the switching to Lightroom CC that they had hoped for.

If I had to guess, Adobe misjudged how much “serious photography” and “mobile phone photography” were likely to converge. They thought that mobile phones would become more of a serious photographic tool, and that Lightroom-type manual adjustments would become more popular on phone posts to social media. The two never really converged, and Adobe hasn’t really found their way into the mobile world. There have been companies that spanned the two worlds.

Kodak in the film era was the classic example. They made disposable cameras and minilab supplies for the Instamatic market that preceded the Instagram market, while they were also making 8×10” sheet film and selenium toner for a totally different customer. There was never a convergence, though – they weren’t selling selenium toner to use with Kodacolor Gold 800 in your Disc camera. Adobe wanted to serve both markets, but they were trying something even more audacious – both markets with the same product. It didn’t work and they realized it in time that they didn’t end up cancelling LR Classic.

Most photographers who use raw converters are thinking about a more or less conventional workflow, and the raw converters will keep adding features as they have been. We’ll probably see a few more “convergence” products like the Fujifilm/Adobe transmission solution, but we’re mostly looking at editing on a computer after photographing with a camera. The definition of “computer” will continue to get wider – iPads are very viable editing platforms, mostly lacking software.

One thing to watch is whether 2023 becomes the year of the iPad for editing. Any Apple Silicon native photo editor or raw converter is already 95% of the way to having an iPad version – and most things are Apple Silicon native now. Capture One already exists on the iPad, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see DxO PhotoLab (which is fully Apple Silicon native) join it. Will Adobe bring Lightroom Classic to the iPad? Technically, it’s easy – it’s fully Apple Silicon native, and Adobe has user interface design experts. It would require admitting that Lightroom CC was a flop, though. Will Adobe take this final step to admitting they got New Coked?

Annual updates may transition to adding features throughout the year, as the software companies keep trying to lure us towards subscriptions. Capture One just changed the economics of the buy vs. subscribe decision by saying that buyers won’t get incremental upgrades until they buy the next big upgrade. The more features they dribble out off-cycle, the more that matters and the more the subscription makes sense. Adobe has been subscription-only for years, and they still release most features in two big annual releases, though. The big one is at Adobe Max in the fall, and they always throw a few things in in the spring as well.

We’ll certainly see more and more AI-powered features, partially in the DxO sense, using AI to empower photographers. Everything that DxO does with AI is manually controllable – it’s just a better version of an existing adjustment. We’ll also see more and more Luminar-style “fix my photo for me” AI.

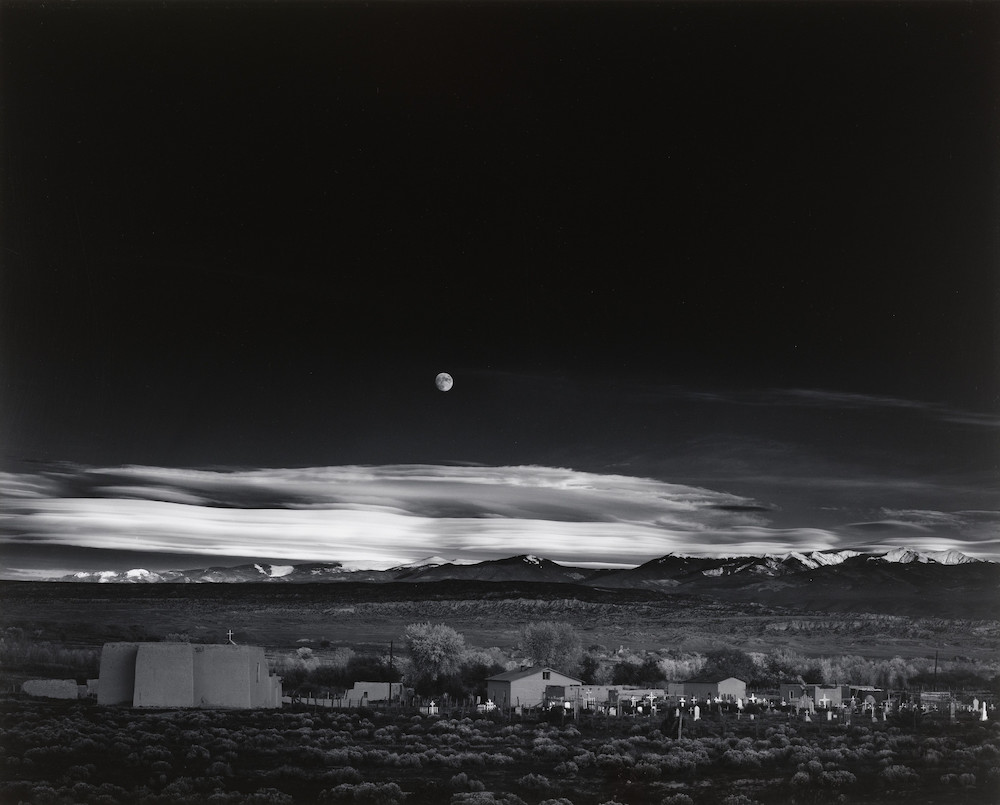

Where I am the most concerned about AI is in what MidJourney and Stable Diffusion are doing – creating images that never existed, making art without artists. These tech companies are training their models from existing artwork, without compensating the human artists whose visions they are, frankly, stealing. Some of their decisions are appaling. AI-generated portraits of women often tend to be highly sexualized, and images of people of color often play on racist stereotypes. There are human biases behind the robots, and those biases along with a thirst for money and a disrespect for artists are driving the algorithms. There is another problem as well – one of the social purposes of landscape photography, and one of the reasons I am a landscape photographer, is to connect real people to real places. Would Monolith: the Face of Half Dome have the same meaning if Half Dome didn’t exist? Ansel Adams stated that there are at least two people in every photograph – the photographer and the viewer. MidJourney and the like threaten both – the art is created without a human creating, and it is created from robots viewing art. AI-generated art is using artists without souls to create landscapes that don’t exist.

The next installment of this piece will focus on the things that are often discussed, but are, in my opinion, unlikely…