I get 100 or more deal notices each month, and almost never pass one on, but this is worth it…

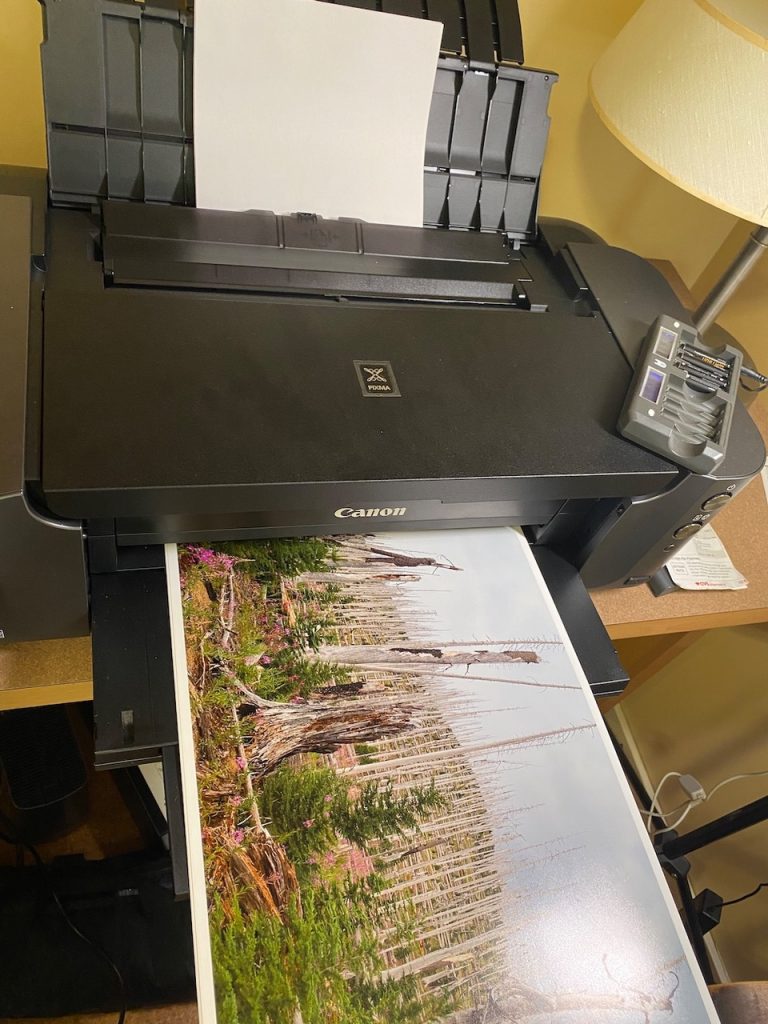

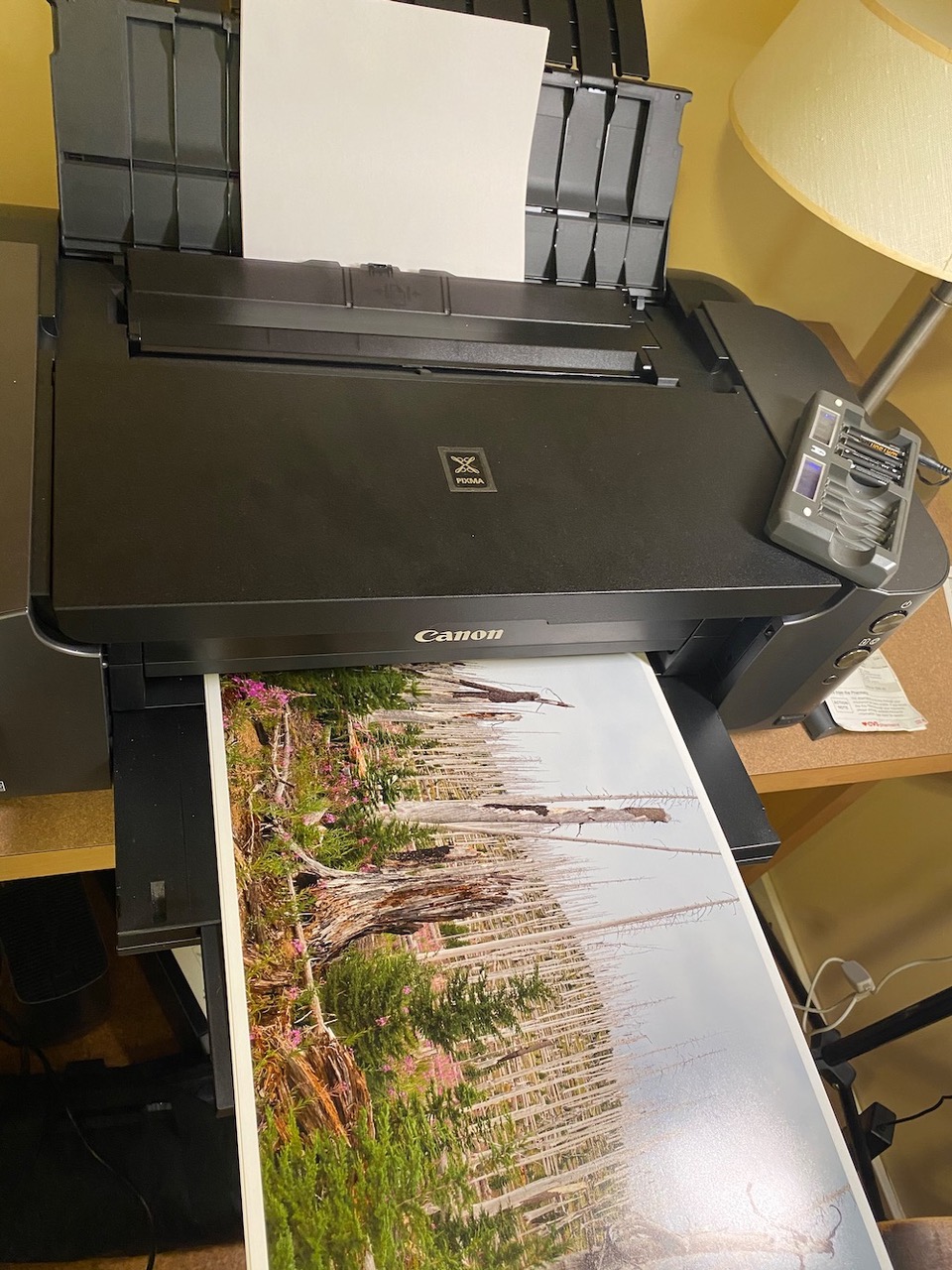

For those who have been following the printing series, Hunts Photo and Video in Massachusetts has an excellent opportunity to get into serious photo printing. They have the Canon Pro-10 (Highly Recommended as an entry-level printer, Recommended as a mid-range printer) for $179 after a pair of rebates, and they are including a 50 sheet pack of Canon Luster or Semigloss photo paper (about $50 worth of paper). $129 net for a serious art-capable photo printer is a great way to try printing if you’re interested.

The Pro-10 is an older model, and I’m sure Hunts got ahold of a bunch them as Canon clears them out to make room for a new model, but it is a serious photo printer with a last-generation 10-color inkset capable of making excellent prints, and it is selling for the price of a five or six color printer. The printer and paper bundle appears to sell for $749, but there is a $320 instant rebate (you never pay that one), bringing it down to $429. Then there is a $250 mail-in rebate from Canon (you do have to pay and it takes several weeks to get that one back) that gets the final cost down to $179.

This is a great deal for a competent printer that will get you started on serious photo printing, or it can serve as a second printer for a photographer who wants something movable (~40 lbs) and with good sheet handling to go along with a roll-fed monster. I own one personally as a second printer. The ink cartridges are small, but you’ll pay 3-4 times as much for anything with comparable print quality and larger cartridges. Any current operating system will drive it (and it shouldn’t be made obsolete terribly soon, since both MacOS Catalina and Windows 10 use new drivers, there shouldn’t be any big changes in the immediate future).

I have no connection to Hunts, except as a very long-time satisfied customer, and neither Luminous Landscape nor I profit from this deal in any way. I have been buying from them since the late 1980s, when I bought my first camera in high school, and have always been happy with them.

Raw Conversion

Phase One just announced a couple of updates to Capture One that are worthy of note for those contemplating a move away from Lightroom. There is now a Nikon-specific version of Capture One, joining Fujifilm and Sony-specific editions (plus a specific edition for the uber-expensive Phase One digital backs, which is free if you happen to own the $20,000-$45,000 back). If you only use one camera system and it is Fujifilm, Sony or Nikon, Capture One costs either $129 one-time or $9.99 per month. Each time Phase One releases a specific version, it is a product of a partnership with the camera manufacturer, which also means that they have access to data that let them fine-tune their camera profiles (improving color for that manufacturer’s cameras). Will Canon, Olympus, Panasonic and Pentax join the list?

There is also a free, feature-reduced version (Capture One Express) available for cameras from any of the three partnership manufacturers. If you are looking for a free raw editor and are willing to put in the time to learn Capture One, Capture One Express is far more capable than the editors built into operating systems or anything else free or really cheap. If you want to try Capture One and have an Express-eligible camera, it’s a great way to try it. If you like it and want to move to the full feature set, $129 one time or $9.99 per month is significantly cheaper than the multi-system version. ‘’

The second major update to Capture One is more modern healing brush tools. Until now, Capture One had lacked the smart healing tools that have been added to most competitors over the past few years. Their version debuts today – I haven’t tried it yet, but Phase One has generally had a good record on releasing things when they’re ready – I’d be surprised if it didn’t work quite well. There are a couple more new features including an improved Lightroom import tool and a before and after view that shows the effects of your edits.

Capture One is the best raw processor available for Fujifilm X-Trans files (which overall quality champ DxO Photo Lab doesn’t support), and it is second in quality to DxO Photo Lab for most cameras supported by both, with more integrated functionality. Both Capture One and DxO offer good free trial periods, so it’s worth trying both out.

The Survival of Camera Companies…

Camera sales have been declining for years, and the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t made it any easier. There are pretty clearly more digital camera companies than the market can support – seven companies trying to sell mass-market cameras (Canon, Sony, Nikon, Fujifilm, Olympus, Pentax, Panasonic) plus two boutique firms (Leica and Hasselblad) at the high end and one tiny firm (Phase One) at the very top of the market.

They fall pretty neatly into three size categories (by the size of their camera business alone – some small camera businesses are part of much larger companies), and the larger camera businesses are going to have an easier time maintaining market share and spreading their research and development expenses over more cameras and lenses sold. A large company with a small camera business can prop it up for a while if it has synergistic benefits for the rest of the company. This is probably what Olympus is doing – they are an optical firm that mainly makes medical optics, some of which have imaging capabilities, and a lot of research is probably shared among divisions. A large camera business is worth keeping around, and is relatively likely to be self-supporting.

There are three big players – nobody will be surprised to learn that they are Canon, Nikon and Sony. Nikon, probably the smallest of the three, makes it easier by reporting financial results for the camera business that are pretty much “clean”, not as part of a larger business unit. Nikon has a camera business worth about 300 billion Japanese Yen ($3 billion US) in annual revenue (Yen to US dollars is about 100:1 – the exchange rate on May 18, 2020 is 107:1, but 100:1 is an easy calculation). Nikon Imaging is about 40% of Nikon, Inc. Nikon’s other large business, around the same size as the camera business, is lithography machines, which are used to make microchips and flat panel displays. Nikon has two smaller businesses – healthcare equipment and industrial measuring equipment – which combine to make up the last 20%.

Both Sony and Canon bury their camera businesses in larger divisions and don’t report results separately, but it’s possible to get some idea. Sony’s camera business plus their substantial camcorder and cinema camera business plus a small amount of healthcare equipment is combined as Sony Imaging Products and Services, with annual revenues of 660 billion Yen. Their image sensor business is a separate division, Sony Semiconductor, and is somewhat larger, but on the same scale (most of that business is huge numbers of small, cheap sensors for phones and the like). How much of Sony Imaging’s 660 billion Yen is still cameras? It’s probably over ½… Is it as much as 2/3? Anyway, Sony’s camera business is at least comparable in scale to Nikon’s, and it’s certainly not twice the size. Sony Imaging all told is only 8% of the Sony Group – the largest single share of Sony is the Playstation business (27%), followed by movies and music (20% combined), financial services (15%), TVs and other entertainment gear (13%) and semiconductors (10%).

Canon’s camera business is included in an 800 billion Yen business unit, lumped with home and office inkjet printers, large-format printers, minilab equipment, scanners and (oddly) calculators. Their camcorder and cinema camera unit is in another division. Cameras are the largest portion of that, but they also sell a lot of inkjet printers. Canon is certainly the leader in market share, but quite a bit of that is inexpensive APS-C DSLRs, while Sony and to a lesser extent Nikon are selling more expensive full-frame cameras. There are no good breakout statistics, but my best guess is that Canon’s camera business is somewhere around 450-500 billion Yen annually. Apart from their camera and inkjet business (22% of the company), Canon is largely an office equipment company – 48% of Canon’s business is laser printers and copiers, ranging from desktop laser printers to huge digital presses (the inkjets are in the camera business, but the lasers are in office equipment). The remainder of Canon’s business is medical equipment and a large catch-all category that includes everything from security cameras to semiconductor lithography equipment.

None of the big three are going anywhere unless the coronavirus is much worse than we think (if, for example, it takes three to five years to find a vaccine – unlikely but possible – all bets are off). Canon and Sony are huge companies of systemic importance to Japan, and their camera businesses are prestige segments of their business. Cameras are a small portion of Sony overall and not a big piece of their history – but they are how Sony shows off their sensor technology to the world, in the same way that car companies build race cars to show off their engineering prowess. As a very public-facing company, they like having the product line that gets a lot of professional use. Canon is historically a camera company, and their corporate image is deeply tied up in cameras, plus they are the market leader. Even if the 9 million camera per year market goes down to a couple million cameras (five or six million is much more likely) , Canon and Sony will be there.

Nikon is a slightly different story – there will be Nikon cameras and Nikkor lenses, but Nikon could be an attractive target for a takeover. Nikon is a significant company, but they are not huge, and both of their businesses (cameras and semiconductor manufacturing equipment) could be attractive to the right buyer. A big tech company could buy Nikon essentially from petty cash. The most likely buyer would be someone who wanted both the camera business (to sell cameras to consumers and professionals) and the semiconductor equipment business -probably for internal reasons.

Apple, Samsung or even Sony or Fujifilm come to mind (among others). Any of those four could use the semiconductor equipment business. Apple designs chips and sends them out for manufacturing, but they are so big and so innovative that building their own fabs is not a stretch and owning a company that makes the equipment that goes in them would allow them to customize the process from the very beginning. Apple’s not interested in selling fabrication equipment or making chips for other people, but they could be interested in rolling their own from the very beginning stages – and they use a LOT of chips. Samsung owns chip fabs and buys the equipment (sometimes from Nikon) – they’re big enough to make their own, too. Sony owns some fabs, and are trying to grow their semiconductor business – making the equipment would be useful. Fujifilm is not a chipmaker, but they sell enough large technical equipment that the lithography machines would be a good addition.

Any of the four would also be interested in the camera business. Apple isn’t a camera company at all, but they make a huge amount of their money on photography. Right now, they have a problem – if someone gets into photography by way of the iPhone, but wants something with a bigger sensor and a zoom lens that still works with the Apple ecosystem, they have nothing to sell. The easiest way to fix this is to buy a camera company… At first, the effects would all be positive – let some Apple engineers loose on Nikon’s menu structure! SnapBridge for iOS is functional, but it’s a mess – what if it became Apple internal software? Or even just part of Photos? It’s really just software, which Apple is very good at, to blend Nikon cameras into the Apple ecosystem… Hopefully, Apple would let Nikon engineers continue to design the camera hardware – I don’t want to lose shutter speed dials to a touch screen. Samsung has a similar argument as a leading phone maker, and they actually made quite a few compact cameras and a few mirrorless models. They never gained much market share, but buying 25% of the market is appealing.

Sony or Fujifilm, who already make cameras, would have to decide which mounts to keep. Sony could really use Nikon’s optical design team – combining them with the designers they already have from Minolta would give them easily the world’s leading lens shop. Sony also doesn’t make optical glass, which Nikon DOES. The question would be whether to keep the technically superior Z mount or the popular FE mount – two lines of full-frame mirrorless bodies with different lenses don’t make much sense. Unfortunately, they are not easily adapted in either direction. Fujifilm has an easier mount question – the Nikon and Fujifilm lines are almost eerily synergistic. What Fujifilm has is high-end APS-C and medium format, while Nikon’s strengths are entry-level APS-C and full-frame. Put an X mount on the low-end APS-C bodies as they transition to mirrorless, keep the F and Z mounts at full-frame, and you have a combined strategy of three mounts (plus F as the transition occurs) and three format sizes. X mount APS-C, Z mount full-frame, GFX mount medium format. Make an adapter from F to X mount (FTX) that is as good as the FTZ, and 60 years of Nikkors work beautifully on APS-C bodies (which also have a great dedicated lens line from Fujifilm) as well as full-frame.

Neither of the other “big three” camera companies are anywhere near as appealing as takeover targets. Canon could appeal to the same kind of companies that Nikon could, but the other businesses are a much larger share of the company, and they’re much less appealing. No forward-thinking tech company wants a large copier business unless they’re already in that business. Fujifilm IS already in the copier business, but they’re not big enough to buy Canon easily – it would be close to a merger of equals. HP could conceivably buy Canon to get the copier and printing businesses, but would probably spin off the camera business (or never buy it in the first place).

Sony is simply too big for any but a very few companies to swallow, and they probably wouldn’t sell just the camera business, which is synergistic for a large electronics and entertainment company. The only companies that could (and realistically might want to) buy Sony are the very largest of the tech giants – Apple, Google (Alphabet), Amazon etc. The camera business would be a minor piece of a takeover that was aimed at PlayStation, Sony Pictures and the record labels. It would be a tech company that wanted the content businesses, and it would have to be a very, very large one – even Google or Apple would emit a noticeable burp upon eating Sony. The camera and semiconductor businesses might even get resold soon after the acquisition, since a buyer would probably be after the entertainment side of the company.

Apart from the big three, there’s probably room for one more real player, perhaps in addition to some hobby businesses. Unless Fujifilm merges with another player, my guess is that the remaining company is Fujifilm. Their digital camera business is almost half the size of Nikon’s (129 billion Yen last year), and it is a small but profitable, historically important (Japanese companies care about their history much more than many others) and highly visible piece of a much larger company. Their camera line keeps gaining market share at a percent or two per year, and they’re strongest among the most likely people to keep buying cameras – they have very little presence in the entry-level market, at least in the West, while serious amateurs and many professionals love them. Their APS-C lens line is unique, while their medium format line is the only one that can split development expenses with another viable camera line.

Pentax, Olympus and probably Panasonic are much smaller camera businesses, and may have a hard time covering development expenses. Panasonic, of course, is a huge company – but the camera business is a tiny part of the overall picture. The camera division is buried inside an appliance business that is itself buried in the larger company. It receives very little attention in the annual report. Unlike Fujifilm and Canon, the small camera business is not historically important to the company. The camera business makes little sense, except that Panasonic has a strong professional video division in another part of the company – could some of the hybrid cameras like the GH5 and S1H end up getting transferred to the video division? If so, what’s worth keeping – does the S1r make sense because it shares a bag nicely with the S1H?

Both Pentax and Olympus have tiny camera divisions. Olympus’ unprofitable camera business brings in about 1/3 the annual revenue of Fujifilm’s (48 billion Yen), which has been falling. They have been releasing cameras based on the same sensor for four years. They have some wonderful technologies, especially surrounding image stabilization. The most likely route to any sort of continued relevance for Olympus is somebody buying the camera business, which is a small fraction of a large medical optics company. As far as I can see, the most likely customer is Sony, who could use Olympus’ lens design experience to augment their own, and might be able to use the stabilization-related patents as well. If the Micro 4/3 line were to continue at all, Sony ownership might allow access to newer sensors.

Pentax’s tiny camera business is less than half the size of Olympus’ (20 billion Yen last year, including 360 degree cameras and waterproof compacts as well as DSLRs). Pentax is a trivial division of Ricoh, and makes so little difference to the larger company’s bottom line that it is hard to find in the annual report, and left out entirely from strategic planning. The information they release gives no idea whether it’s profitable, but it is too small to be worth much development expense. Even Ricoh themselves admit that Pentax cameras appeal almost exclusively to existing users. Is it worth continuing to produce a few cameras based on purchased sensors and other existing parts? New “Pentax” lens designs often bear a strong resemblance to Tamron models – they may very well be Tamron lenses with a K-mount attached and a new nameplate. If Pentax survives at all, I certainly wouldn’t expect to see much beyond stock Sony sensors in parts-bin bodies.

Leica, Hasselblad and Phase One are all privately held (Leica and Phase One by private equity firms, Hasselblad largely by Chinese drone maker DJI), so little information is available. Phase One is primarily a software company and Capture One seems to be doing relatively well. Their camera business is so far outside the mainstream that it is tough even to speculate. Much of their business is in areas like aerial photography and document capture. Leica’s camera business seems to be on a similar scale to Olympus (far fewer cameras sold, but at much higher prices), and may be profitable at least in part due to sales of high-priced commemorative cameras. The Leica name is sure to survive, and at least some boutique camera building will probably continue – will they continue to invest in building “modern” cameras, or will they only build a few M models for collectors and aficionados, while licensing lens designs to phone makers? Hasselblad will survive at least as a nameplate on drone cameras, but I am much less certain there will be “real Hasselblads”…

Sure to survive (as independent companies): Canon, Sony.

Sure to survive as a viable system, but could be bought: Nikon

Almost sure to survive: Fujifilm

Likely not to survive without a transfer within parent company: Panasonic

Likely not to survive without a sale (and the sale may be for technologies, not as a viable camera maker): Olympus

On life support: Pentax

If you have Canon, Sony, Nikon or Fujifilm gear, your system is very likely to remain under active development. These brands are all worth buying into now, and while mergers might affect one or two of these companies, their user bases are large enough that they will continue to be supported. In an odd sense, the greatest (but still small) risk in this group may be Sony, because it is the only one of the four that is not a long-time camera company, and it is the only one that could be acquired by a buyer that wasn’t interested in the photographic business. Even so, a buyer who was primarily interested in the entertainment assets would probably sell or spin off Sony Imaging instead of letting it die.

All of the remaining camera makers are at some significant level of risk. It would be a tough choice to begin acquiring any system outside of the four major players. If you already have a system from one of them, is it worth adding to? Pentax has a huge back catalog of used lenses, and the major reason to use a Pentax body is beloved vintage lenses, so it could well be worth buying a replacement or additional body if you intend to use those lenses. Bodies will run out long before the lenses do. The same is true, although less so, of Micro 4/3. Even if both Panasonic and Olympus cut off body and lens supplies tomorrow, there is still a lot of used gear. The real problem there is the lack of newer sensors.

Leica M is always an emotional decision, and I see no reason why it won’t remain hand-built in limited numbers as it has been for decades (M lenses last forever, and there will be a healthy used market far into the future). I’d hesitate to buy into the S or L mount systems, at least until seeing if Panasonic and Sigma make real commitments to L mount. L mount could end up very viable, especially for video, if Panasonic puts a lot into it and moves it to their video division, and it could end up dead. S mount may be like M mount, never made in large numbers, but always around – or it could vanish. In medium format, the safe choice is Fujifilm or possibly Phase One. DJI bought Hasselblad first for the name and then for technologies – how actively they continue in medium format is unknown.

Slow Lenses

I continue to be distressed by the prevalence of very slow lenses among recent introductions. There are three reasons a photographer might want a faster lens. One is to get more light to the sensor to allow a lower ISO or a faster shutter speed. The second is to control depth of field, and the third is diffraction effects (some very slow lenses may have no optimum aperture, because they are diffraction-limited wide open).

Modern sensors are so good that the “more light” reason has declined in importance in recent years for many uses – although, if you’re printing really big, the absolutely noiseless low ISOs on many recent cameras are worth using, and you do need a lot of light for those. If you’re shooting sports, wildlife or anything else that requires very high shutter speeds, more light is equally welcome. Sensor size and sensor density don’t matter from a pure light perspective – an f2 lens always lets in the same amount of light.

Smaller, older and higher-resolution sensors are often inherently noisier than big, new, modest-resolution sensors. The noisier your sensor, the lower you’ll want to keep your ISO, therefore the faster the lens you’ll need. Of course, if you have a high-resolution sensor, you can always downsize to control noise – unless you’re making a really big print and need all the pixels. A good modern sensor is very low-noise up to about ISO 400 or higher, and not terribly noisy up to something much higher (ISO 3200?), especially for screen display.

By far the noisiest sensors on any interchangeable-lens camera sold today are Micro 4/3 sensors – they have two disadvantages. First, because of the small sensor size, they have very high pixel densities to keep resolution competitive. A 20 MP Micro 4/3 sensor has pixels as small as a (nonexistent) 80 MP full-frame sensor. Second, they’re among the oldest sensors on the market – the current 20 MP sensor dates back nearly four years to the introduction of the E-M1 mk II. The high density coupled with the older sensor lacking some of the newest technologies mean that Micro 4/3 requires lower ISOs and faster lenses than other formats.

If you’re printing big and high-quality, there is a noise advantage to the very lowest ISOs – ISO 64 on a modern Nikon is a sight to behold – it really is different from the low-limit ISO 100 on most other cameras, and you’ll notice it in the shadows on big prints. The D850 and Z7 at their very low base ISO are the least noisy cameras I’m aware of (apart from the GFX 100, which is in a class of its own in a lot of ways – including image quality, but also cost and weight). It is hard to use a f5.6 lens at ISO 64, unless you have a lot of light. The excellent image stabilizers in the Nikons really help, but image stabilization doesn’t stop subject motion! You might want a faster lens with a modern Nikon with ISO 64, not because you were afraid of high ISOs, but because the low ISOs are really special. You can push the Z7 (or the D850) and still print big, but its ultra-clean low ISOs produce a medium-format (or even large-format film) look.

For depth of field control, the size of the sensor matters, as does the focal length of the lens – the resolution of the sensor does not. Roughly, anything slower than f4 or f4.5 on a full-frame camera is a notably slow lens with limited DOF control, unless it is a long lens. A 500mm f5.6 can offer razor-thin depth of field because it is so long, while f5.6 is a slow lens even at 200mm. Anything in the range of f1.8 to f4 is a medium-speed lens, with a significant difference between the slower and the faster ends of that range. Medium-speed lenses (many primes and higher-end zooms) offer significant control of depth of field, and DOF control becomes very good at the longer and faster end. Again, very long lenses that might be counted as medium-speed if they weren’t as long are actually fast (e.g. a 300 or 400mm f2.8). Anything faster than f1.8 is unequivocally a fast lens. Fast lenses offer complete control of depth of field, and you can always stop down a fast lens as an artistic choice to bring more into focus, while you can’t open up a slow one.

If your sensor is APS-C, lenses behave as if they were one stop slower for depth of field purposes, although they also behave as 1.5x longer. Fast lenses need to be faster than f1.4, and f4 lenses start to be slow in a way they are not on full-frame. A 75mm f2 wide-open on full frame is very similar to a 50mm f1.4 on APS-C, both in coverage and in depth of field. In that case, no problem – both lenses are readily available, and neither is more exotic than the other. Where this equivalence becomes an issue is if you were using a 50mm f1.4 wide open on full-frame. The APS-C lens that offers similar coverage and depth of field is a 35mm (no problem there), but it is a 35mm f1.0 (that rapidly becomes a problem – although Fujifilm is releasing one).

At the long end of the range, a 300mm f2.8 on full-frame is very closely equivalent to a 200mm f2.0 on APS-C. A 200mm f2.0 is somewhat hard to find, although Fujifilm (again, they really DO have a wide APS-C lens range, and they think about equivalence) makes a nice one, and it is in very much the same size and price range as a 300mm f2.8. An APS-C 200mm f2.8 is substantially smaller, lighter and cheaper than a full-frame 300mm f2.8, and it has similar coverage, but it does not have similar DOF properties. It’s more like a 300mm f4, and the size, weight and price range of a 200mm f2.8 is very similar to that of a 300mm f4. The smallest and lightest lens in that category is actually a 300mmf4 – it’s Nikon’s wonderfully compact PF lens.

Zooms tend to be a bit slower from a depth of field perspective on APS-C than they are on full-frame. A 16-55mm f2.8 APS-C lens is similar to a 24-70mm f4 on full-frame (it’s a bit longer at the long end). Nikon makes a very sharp full-frame 24-70mm f4 for their Z system, and it’s actually almost 30% lighter than Fujifilm’s equally nice 16-55mm f2.8. The Fujinon is almost exactly intermediate in weight between the f4 Nikkor and the 24-70mm f2.8 Nikkor for the Z cameras, which is a stop faster for depth of field purposes.

You’ll rarely see an APS-C zoom that’s a stop faster than its full-frame counterpart to compensate, although they do often have some extra reach at the long end. What you do sometimes see, and they can be a real advantage to APS-C, is very small and light slower zooms with excellent image quality. Fujifilm’s 18-55mm f2.8-4 is an example of the breed – its full-frame equivalent would be a 26-85mm f4-5.6. Lenses like that exist, but they are almost always optically questionable kit lenses – the Fujinon is a little gem.

The issue gets a stop worse at Micro 4/3 – any lens of modest focal length slower than about f2 or f2.4 is a slow lens, and a truly fast normal or wide lens has to be around f1.0. This, of course means that all zooms are slow lenses on this format – none of them offer much DOF control – there are no f2.0 zooms at all for Micro 43. Even the pro-level constant-aperture f2.8 zooms (many of which are notably sharp lenses) behave like a constant f5.6 lens on full-frame. The one possible exception is the long end of the 40-150mm f2.8 – 300mm f5.6 equivalent could easily be considered a medium-speed lens. Any constant f4 zoom, including Olympus’ new 12-45mm f4, is equivalent to a constant f8 lens on full-frame. Their new, expensive 150-400mm f4.5 telephoto zoom is going to have the DOF performance of an f9 lens. Admittedly, it will be a handholdable 300-800mm f9 lens, which is just about impossible to make on a larger format – although what about a Canon DO or Nikon PF lens with a teleconverter? The somewhat smaller and lighter Nikkor 500mm f5.6 PF becomes a 720mm f8 when used with a 1.4x converter, and it can be used on a 45 MP sensor instead of a 20 MP sensor…

There are some nice medium-speed primes, many of which are exceptionally small and light. They tend towards the slower end of medium – remember that an f1.8 lens behaves like an f3.6lens on full-frame. A very sharp f3.6-equivalent prime is still a very useful lens, especially when three or four of them fit in a coat pocket. Not since film-era Summicrons has there been such a nice collection of tiny, relatively slow lenses…

Getting into faster lenses, the f1.2 M.Zuiko Pro lenses, while not tiny, are similarly sized to full-frame ~f2 primes of twice the focal length. The 25mm f1.2, for example, is very similar in size and weight to the 50mm f1.8 Z Nikkor, a full-frame mirrorless lens of very similar focal length and only slightly different depth of field (the Nikkor is slightly faster from a DOF perspective). The Olympus lens is close to twice the price of the Nikkor, and both are excellent performers.

The third reason slow lenses are less than ideal is diffraction. Diffraction is a phenomenon of optical physics – light is scattered by passing through the aperture and a ray that would have hit a single point with no diffraction blurs into a pattern called an Airy disk. Since the size of the Airy disk is dependent on the wavelength of light, there’s no single number that says “below this aperture, diffraction will have no effect, above it, it’ll blur your pictures” – it gets worse as the aperture gets smaller. Some very slow lenses are diffraction-limited at all apertures – their widest aperture isn’t wide enough to use the full resolution of the sensor.

Diffraction limits depend on pixel size, not on sensor size. A 26 MP APS-C sensor will have exactly the same diffraction issues as a 60 MP full-frame sensor, since they use the same pixel size. Roughly speaking, diffraction begins to be an issue around f5.6 or f6.3 for the very dense Micro 4/3 sensors and the new Canon 32 MP APS-C sensor (remember that a 20 MP Micro 4/3 sensor would be a ~80 MP full-frame sensor – so would the new Canon 32 MP sensor). Somewhere around f7.1, diffraction begins to set in for most high-resolution sensors – whether they are 24-26 MP APS-C or 40+ MP full-frame. 24 MP full-frame sensors are not diffraction limited until between f9 and f11. There is also not a sharp line between diffraction and no diffraction – an image at f8 on an A7rIV would technically be diffraction-limited, but the diffraction effect would be minimal. An image made with the 32 MP APS-C EOS-90D at f22 (a worst case scenario) would be very severely diffraction-limited.

Until recently, there were no interchangeable lenses that were diffraction-limited wide open (except for super-cheap no-name manual focus extreme telephotos with maximum apertures around f11 or f13 and the occasional pinhole Lensbaby). Lenses simply weren’t slow enough, nor sensors dense enough. Most films aren’t diffraction-limited until around f22 or f32, and the long-lived 6 MP APS-C sensors were diffraction-limited somewhere around f16.

As sensors got denser, there were certainly lenses that never reached optimum performance – say a 70-300 f4-5.6 on a D850 or any 24 MP APS-C camera. A consumer zoom like that probably needs to stop down two stops for best sharpness – that’s f11 at the long end. A D850 is significantly diffraction-limited at f11. The best compromise is probably to shoot the lens at f8 – stopped down 1 stop to improve sharpness, accepting a bit of diffraction. There are also lenses that simply aren’t sharp (many inexpensive kit lenses) – a diffraction-limited lens can’t get any sharper due to optical physics, while a lousy lens won’t get sharper because of bad design, construction or materials.

Unfortunately, with the trends towards slower and slower kit lenses and denser and denser sensors, there are now mainstream lenses that are diffraction-limited wide open. Many phone camera lenses are diffraction-limited wide open, including most phones with resolutions above 20 megapixels or so as well as some below that. Any phone that claims a resolution above 40 megapixels would require BOTH a sensor with a 1/1.8” diagonal (larger than a conventional phone sensor) AND a f1.4 lens, which is too big to fit in a phone for a sensor with that diagonal. These phones tend to bin pixels, which does reduce or eliminate diffraction, but also reduces resolution (in binned mode, they tend to be ~12 megapixel sensors, just like phones that don’t claim the huge numbers to begin with).

Compact cameras tend to be diffraction-limited wide open at the longer end of the zoom range, where apertures are smaller. Some of the larger-sensor compacts with fast, but not terribly long lenses can use their full resolution through their entire zoom range. Kudos to Sony – none of the 1” sensor RX100 range are diffraction-limited at maximum focal length and maximum aperture. Stop down and they are, but it’s always possible to hit diffraction by stopping down too far. On the opposite extreme, Nikon’s ultra-long telephotos in the Coolpix P series are probably the most severely diffraction-limited lenses on the market. The Coolpix P1000, with its absurd 24-3000mm equivalent focal length, is diffraction-limited even at the WIDE end of the range. At 3000mm, its 16 MP sensor is limited to under 2 MP of effective resolution. Yes, it’s a very long lens, but remember that its maximum resolution is equivalent to a Coolpix 950 from 1999 at the long end.

Among interchangeable lens cameras, slow telephoto zooms and kit lenses are the most likely lenses to be concerned about. Most of these lenses are not only diffraction-limited wide open, they also need to be stopped down a couple of stops for best performance, worsening the diffraction problem.

Here’s the rogues’ gallery of interchangeable lenses that can’t fully use your sensor due to diffraction alone, without any regard to whether the particular lens is sharp. Shame on their manufacturers – note that just about everybody has a lens or two on this list. This list includes all lenses from major manufacturers slower than f6.3 plus f6.3 lenses that could end up on a camera body with a dense enough sensor that they are diffraction limited wide open.

There are a bunch of other f6.3 lenses lurking just off the list, which one more slight jump in sensor resolution will add to the rogues’ gallery. I have not included very inexpensive, slow manual-focus telephotos (some primes, some zooms, some mirror lenses) that are sold under several manufacturer names, nor have I included Lensbabies, macro lenses beyond 1:1 and a few other special-effects lenses. There are two basic types of lenses on the list, plus one unusual body cap lens. Several of these lenses plus quite a few other f6.3 lenses that barely miss the list are inexpensive kit lenses engineered for cost and size, instead of optical quality and speed. Kit lenses have no business being this slow – they should top out at f5.6, and preferably f4.5 or so.

The second problem with slow kit lenses that are diffraction limited or nearly so is that they generally aren’t terribly sharp wide open. If a lens is right on the edge of diffraction wide open, it’s showing significant diffraction stopped down one stop, and severe diffraction stopped down two stops. A lot of those kit lenses need two stops to sharpen up, if they ever do. Sony’s execrable little 16-50mm power zoom that they supply with many of their APS-C bodies is a “shining” example of this breed. It’s f5.6 at the long end, and a 24 MP APS-C sensor doesn’t hit diffraction until around f7.1, but the lousy lens simply never sharpens up – it was built for cheap and compact, not sharp, and it shows. Between diffraction increasing as you stop down and poor wide-open sharpness, there are a lot of kit lenses that have no very good apertures, and some that really have no acceptable ones.

Most of the rest are zooms that reach very long focal lengths. Some of the big zooms are just sloppy design or cost-cutting – 100-400mm lenses always used to be f5.6 at the long end, and that can technically take a 72mm filter size, although 77mm is more reasonable, and even 82mm is not uncommon. Others are lenses that get really long. Nikon has a reasonably priced 200-500mm that’s a constant f5.6, and it‘s a good, sharp lens – but it’s a big, heavy lens that takes 95mm filters. Nobody has a reasonably priced zoom that goes to 600mm without the compromise of a very slow aperture on the long end – a 600mm f5.6 requires the same size front element as a 300mm f2.8 (mathematically, it has to be at least 108mm – such lenses usually don’t take front filters, but often have a removable protective plate of around 112mm), and that’s a big, heavy, expensive exotic lens. Of course, the Nikon 1200-1700mm zoom (old, VERY special order manual focus lens that was 3 feet long, weighed nearly 40 lbs and cost $60,000) is in a category of its own. Fortunately, the telephotos tend to be designed for wide-open use, so most of them (with the exception of a few cheap lenses) are very usable at maximum aperture with only a bit of diffraction.

F5.6 lenses are not diffraction limited on any sensor yet (about 25 MP Micro 4/3, 40 MP APS-C, 90 MP full-frame)

F6.3 lenses are diffraction limited around 20 MP Micro 4/3, 30 MP APS-C, 60 MP full-frame.

F6.7 lenses are diffraction limited around 16 MP Micro 4/3, 26 MP APS-C, 50 MP full-frame.

F7.1 lenses are diffraction limited around 12 MP Micro 4/3, 20-22 MP APS-C, 40 MP full-frame.

F8 lenses are diffraction limited on any modern camera EXCEPT 24 MP full-frame.

In alphabetical order by manufacturer, the roll of dishonor…

Canon EF-M lenses (diffraction limited at the long end of the range, where maximum aperture is f6.3, on the M6 II and future 32 MP cameras):

EF-M 15-45mm f3.5-6.3

EF-M 18-150mm f3.5-6.3

EF-M 55-200mm f4.5-6.3

Canon RF lenses (likely diffraction limited on the new EOS-R5, depending on final sensor resolution)

RF 24-105mm f4-7.1

RF 100-500mm f4.5-7.1 L (extra shame for calling this an L lens)

Kudos to Canon for NO EF or EF-S lenses making the list – they’re all f5.6 or better.

Fujifilm has one inexpensive lens right on the edge of diffraction limits on the 26 MP bodies. Nothing else is close to diffraction limits, and Fujifilm gets a lot of credit (as does Nikon with the Z full-frame lenses) for having very few lenses slower than f4.

XC 50-230mm f4.5-6.7

Nikon gets an honorable mention for only having one lens on the list, and it’s a lens most of us will never see. If you can find it, afford it, carry it and focus it (none of the above are easy), it’s diffraction-limited at the long end of its range on the D850 and Z7. Note that, ignoring the zoom, it’s STILL a 1200mm f5.6 at the SHORT end! There are a few cheap APS-C Nikkors that are f6.3 at the long end, and just barely miss the roll of dishonor…

1200-1700mm f5.6-8P

Olympus lenses (diffraction limited on 20 MP bodies – the f8 lens is limited on 16 MP bodies as well)

M Zuiko Digital ED 75-300mm f4.8-6.7

Fisheye Body Cap 9mm f8 (special shame because it’s a prime, but some credit because it’s a weird lens)

M.Zuiko Digital ED 12-200mm f3.5-6.3

Panasonic lenses (shame on them because it’s an expensive “Leica” lens)

Panasonic Leica DG Vario-Elmar 100-400mm f4-6.3

Pentax has no lenses on the list – there are a couple of f6.3 lenses that jump on if they introduce a higher-resolution APS-C camera.

Sigma lenses

150-600 f5-6.3 Contemporary (diffraction-limited on Canon 90D)

100-400 f5-6.3 Contemporary (Canon 90D)

60-600 f4.5-6.3 Sports (Canon 90D)

Sony lenses (right on the edge on the A7r mkIV)

FE 200-600mm f5.6-6.3 G (slow at the short end – although it IS a 600mm, and it’s sharp wide open).

There are several f6.3 APS-C lenses – present Sony APS-C bodies aren’t diffraction-limited at f6.3, but it wouldn’t take much more resolution…

Tamron lenses

SP 150-600mm f5-6.3 (Canon 90D)

100-400mm f4.5-6.3 (Canon 90D)

Dan Wells

May 2020

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

You May Also Enjoy...

Hand’s On: new Sony A9III and Sony 50mm G Master, Sony 85mm G Master, Sony 75-350mm APS lenses

A quick hands on look at Sony A9iii and the Sony APS 75-350mm len

The best wide-angle zoom in the world? The Fujinon G5 20-35mm f4 R WR reviewed.

FUJIFILM GF 20-35mm f/4 R WR L