Why Aren’t We Talking About It All The Time?

For years I have been fascinated with how the human eye perceives depth, and particularly with how this relates to the two-dimensional photographic image. Many is the time I have come across a fascinating scene, full of nearby objects in interesting relationships, or perhaps a view of a city plaza, only to find that the photos I snap look like nothing much when I get home. There is an unbridgeable gap between how the brain combines the images coming from two eyes, and how that perception can be approximated in a flat print. This gap is intriguing and frustrating.

For some reason, I’ve never seen this issue discussed in the photography community—on the web, in books, anywhere.

The interesting thing is that we are basically happy with 2D images. Ever since people figured out how to create full 3D stereo images using photography, the result has never been much more than a curiosity. There were stereopticons in the 19thcentury, View-Masters starting around 1940 (we’ve all had them as kids), 3D movies starting in the 50s. 3D TVs were hyped like mad a few years ago, and then just went away. You can still buy stereo cameras, though mainly on eBay, not in stores. (Notice that they aren’t expensive. If enthusiasts cared, they’d be expensive.)

Yes, it’s neat seeing a movie in 3D, but look at the titles – action pictures, animations, special effects blockbusters. Niche. Kids and teens. We should make an exception for Pixar, though. The 3D versions of their animations are truly amazing: “Up” is my favorite. Pixar must be manipulating the apparent interocular distance to create exaggerations selectively. All exciting, never overdone, just wonderful.

So why are we happy with 2D images? I think it is mainly because we’ve achieved such a high degree of visual literacy, absorbing all the ways that depth can be conveyed without stereo vision. Yet it’s clearly also because stereo photography is awkward and inconvenient, so much so that we haven’t been able to pursue stereo photography as art. Artists who are preoccupied with the direct experience of space become sculptors.

Here are some thoughts on what the issues are, and how we might use an awareness of this special realm of perception to improve our art.

Perspective

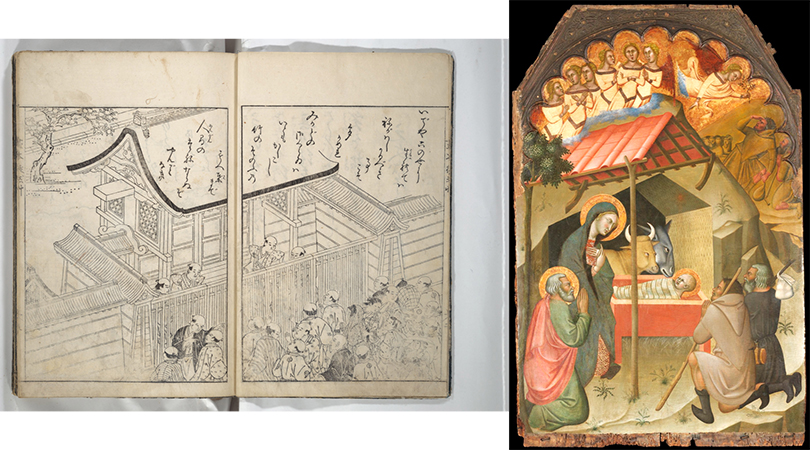

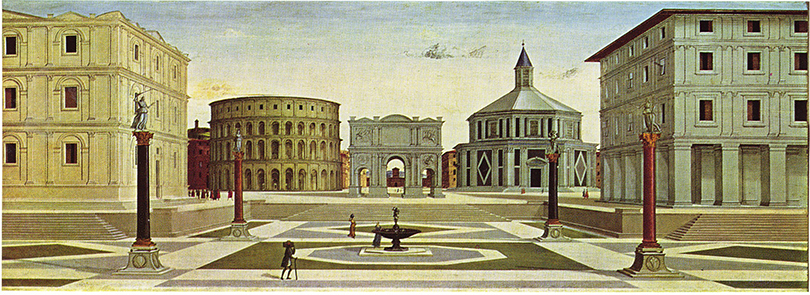

The most dramatic breakthrough in the depiction of depth in two-dimensional art has to be perspective. The Chinese, Japanese, Greeks and Romans used it in simplified form, as oblique or isometric perspective, but they did not understand the concept of a vanishing point (or points). They recognized that objects get smaller the farther away they are, at that angled lines have something to do with it. Usually, they drew the edges of shapes as parallel. Medieval painting in Europe was similar.

True perspective as we know it now was invented, or discovered, by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) in the earliest years of the Renaissance. He painted the outlines of buildings into a mirror, discovering that the lines all converged on the horizon. Our cameras, of course, do this automatically, by the nature of how a lens works.

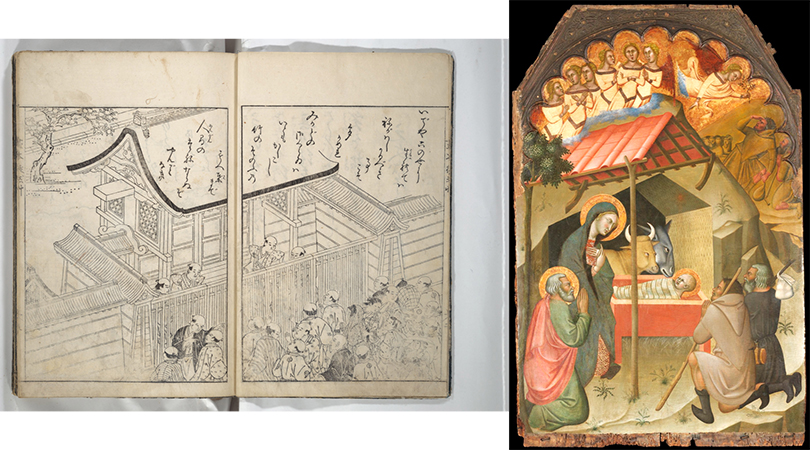

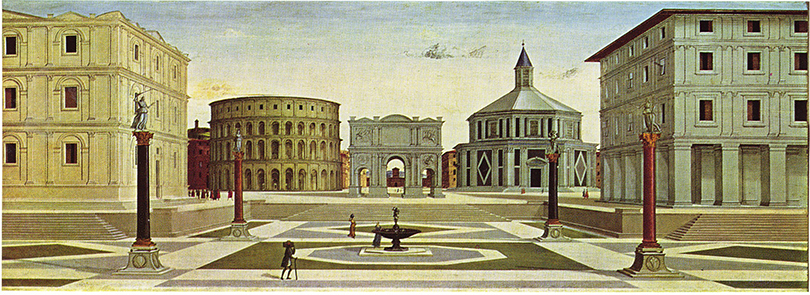

Here is one of the classic early perspective painting—one certainly familiar to art history students.

It’s an imaginary place, probably painted by Luciano Laurana, from the late 1400s. It combines real buildings from around Italy, all done in meticulous one-point perspective (there is only one vanishing point).

So—what happens when the painter begins to place human figures in the landscape? Here’s another classic image, this one by Pietro Perugino in 1481.

He puts all the main figures right up front and spreads some small figures around in the far background. This is like simple augmented reality apps working on a smartphone: you project a lion into your living room and it shows up at an appropriate size for the distance, but it still looks like it’s just hovering there, not really part of the scene.

Perspective all by itself goes a long way to creating depth, but it falls short of realism.

Painters after the Renaissance struggled to fill up the middle ground of paintings in a convincing way, but they had a hard time. This picture by Il Padovano from 1621 isn’t all that much more effective than Perugino’s. There’s an empty gap between the foreground and the background. Even with accurate perspective, it somehow seems unrealistic.

Notice one thing about most of these pictures: there is basically no lighting the perspective areas. Just lines and planes.

Light and Contour

The next way the brain perceives space is through light, shading and contour. To put something convincing in the middle distance, you have to do it with shading and light. To me, this is shown by this breakthrough building by Bramante in Rome, built in 1502, about 100 years after Brunelleschi discovered perspective. Called the Tempietto, it’s a small structure in a tiny courtyard, but it fills up the middle distance like an elephant would: it’s all roundness and shadow, unlike most of the buildings that Renaissance architects were designing up to that time. In photographs, it looks far bigger than it is. Notice at the building to the right—it’s much like the grey building in Il Padovano’s picture behind the Cardinal. It doesn’t convey depth and presence, but the Tempietto next to it really does.

And, as you can see clearly because this is a photograph, our cameras have no more trouble rendering light and shadow than they do perspective.

Before we get to stereo, there are several other ways the brain can perceive depth from a 2D image.

Color and Atmosphere

Because higher frequency light (blue) is bent more by a lens than lower frequency light (red), the two colors come into focus at different distances from the lens, called chromatic dispersion. Most people see one color in front of the other. Some see the red in front, others the blue, so this effect isn’t clear-cut. The field of chromostereopsis is complex, and at least from what I read, doesn’t create consistent effects.

In painting, however, the blue of the sky and the tendency of far-away objects to blend with the atmosphere has at least created a convention of cool colors signifying depth. Look at the mountains in Perugino’s picture, or the famous Washington Crossing the Delaware (Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze, 1851).

This picture has it all: perspective, shading, atmosphere and color cues (red near, blue far) creating a very convincing imitation of depth.

Focus

Our eyes do need to focus, but their focal length is short (about 15-21mm), so they have a lot of depth of field. And they are constantly darting around a scene, from near objects to far, refocusing as needed. As a result, focus isn’t much of a factor to us in perceiving depth, except that it subconsciously provides a cue. We can tell when our eyes are focusing up close because the muscles around the lens have to contract. When you thread a needle, you really notice the effort, but apparently, the muscular effort involved in focusing acts as a subconscious depth cue even at moderate distances.

But things are different in photography. We go to special lengths (and great expense) to create bokeh as a deliberate effect. From a lifetime of watching movies and seeing photographs, we have learned that focus is a tip-off to distance and space, such as in this picture of a baboon beset by antelopes by my friend Kirk Hamilton.

Back to stereo vision

So where does stereopsis (true stereo vision) come in? It’s the only way we perceive depth that we can’t illustrate on a page. It exists only in the brain and in the moment. Close one eye and it goes away. Do we dream in 3D? I don’t know, but I guess I doubt it. The mind’s eye seems to be singular.

Surprisingly, it’s hard to find much literature on this subject. You can view one useful article here. It’s the only one I could find that discusses in detail how far away stereo vision works. Years ago, I came across a reference that said the limit is about 600 feet. This article estimates 248 meters (813 feet), which I would agree with. I think it’s more than 600 feet just by walking around and looking at things. The same article says that “good stereoscopic observers are capable of detecting depth differences corresponding to binocular disparities of only a few seconds of arc… we can calculate that the maximum useful range of stereopsis should exceed 1 km.” (My emphasis. Wow!)

The interesting thing is that the common wisdom, again quoting from this article, was that we are “effectively one-eyed for distances greater than about twenty feet.” Clearly, that isn’t true, but it’s the distance at which stereo is really obvious.

I think I am lucky enough to be one of those “good stereoscopic observers,” because I’m always aware of it when I’m in certain types of settings. Different people are sensitive to stereo vision to different degrees. Some apparently do not perceive it at all, even though their eyes are OK. It is said Rembrandt may have had no stereo perception.

In my experience, stereo vision is confusing in different ways when the scene is nearby (less than 20 feet) and when it is far off.

Nearby scenes:

These are the scenes when you, as a photographer, see multiple objects close up with strong 3D, only to be really disappointed with the results back in Lightroom. I think this happens especially when 3D is the primary depth cue, and the other cues (perspective, color, atmosphere, shading) are weak.

Take a bunch of bicycles parked at odd angles on the street in bright light. Or look up at the branches of a tree from below. Our eyes are operating at maybe f/11 in bright light. For a 17mm lens, f/11 means that, basically, everything is always in focus. Perspective is missing too. We don’t see perspective because the bicycles or tree branches are at all angles, and certainly not lined up to a vanishing point. And there is no atmospheric effect. Our sense of depth when we click the shutter is strong, yet the result is blah – maybe a good photo, but it won’t capture what we experienced.

Far away scenes:

To me, this is where things really get interesting. Looking across the Grand Canyon, way beyond 1 kilometer, we are basically looking at a painting. Close one eye, no difference. But within 1km (optimistically), and especially within 800 feet, 3D vision really adds something. It’s subtle but very real.

I make a mental habit of collecting environments like these. The Pyramid at the center of the Louvre in Paris views across the Seine, the square in front of the palace at Avignon, Times Square, walking across the George Washington Bridge. Night lighting seems to accentuate their fascinating spatial presence.

In this picture of the Louvre, all the visual action is happening near the limits of 3D, and there is lots of sculptural depth and detail on the buildings. There is nothing much happening in the near or medium space (it looks like the Perugino from the 15thcentury). You aren’t confused by the strong stereo depth you would see close by. What you see seems two dimensional, but there is much more going on. Something subtle, but close one eye and it isn’t there.

The lesson here is a little hard to pin down. Does the perception of 3D really change the way we take pictures in 2D? I think it does. If we are aware that our interest in a scene is going to be hard to render because of this effect, we can consciously use the other methods available to try to convey the same thing. Perspective, color, atmosphere, shading and focus.

Look at the pictures of Fan Ho, who died recently. His work with perspective and atmospheric depth is beautiful. Ted Forbes’ tribute is wonderful. He also posts some of Fan’s work on Pinterest here. This collection does exactly what I’m suggesting. It conveys an instinctive and emotional sense of space by strong use of perspective, light and atmospherics. It’s almost like seeing with two eyes.

I am very interested in getting readers’ reactions. Have you felt the same confusion and frustration about why certain scenes don’t work out? Have you collected your own favorite locations for far-3D perception? Do you have ideas about how technology might advance our ability to directly record space in an artistic way? Please share.

Michael Alford

October 2018

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

You May Also Enjoy...

Celebrating Alternative Photography: Cyanotype Prints with Ashok Viswanathan

FacebookTweet By: Ashok Viswanathan – FFIP, EFIAP.PPSA Cyanotype is one of the earliest printing processes, dating from 1842 by Sir John Herschel, shortlyafter the discovery

Celebrating Alternative Photography: Mastering the Van Dyke Process with Ashok Viswanathan

FacebookTweet Long-time Lula member, Ashok Viswanthan, kindly offered to share his approach and methods for alternative photography processes. I hope you enjoy his detailed “how-to”