Complimentary Article

Searching for Edward Hopper

Let me begin by stating that despite its title, “Searching for Edward Hopper” was never a shooting project where I went out looking for Hopper images, but only an exercise well after the fact, a way of looking back at 40 years of my work from a different point of view than I was accustomed to doing. (It’s a great exercise; I recommend it highly.) Only after I was well into it did it occur to me that I might have a book in the making.

When I discovered Edward Hopper in the late 1960s, I was a photographic novice. In some essential way, Hopper’s utterly American paintings spoke directly to me, and opened my eyes to what traditional values had conditioned me to ignore: the ordinary, the everyday, the commonplace. My discovery a couple of years later of Walker Evans only reinforced my interest in the vernacular, and what Evans referred to as “lyric documentary style.” Once I’d learned their way of seeing, it was hard to perceive the world any other way.

For years I bought every Hopper book I could afford, searching through their essays and illustrations for… I’m not sure what: perhaps a talisman of some kind that would lead to enlightenment. Now, decades later, I’ve reached the conclusion that the Edward Hopper I’ve been searching for has been within me almost from the start.

However, this book is really not about Edward Hopper or even about what some have termed the “Hopperish” quality of my photographs. Rather, it is an exploration of the impact Hopper has had on me: ways he has influenced my seeing, how he helped shape my photographic style. Through Hopper’s eyes I learned to see with my own, and whether or not they look the least bit “Hopperish,” each photograph in this book owes something to the influence of Edward Hopper.

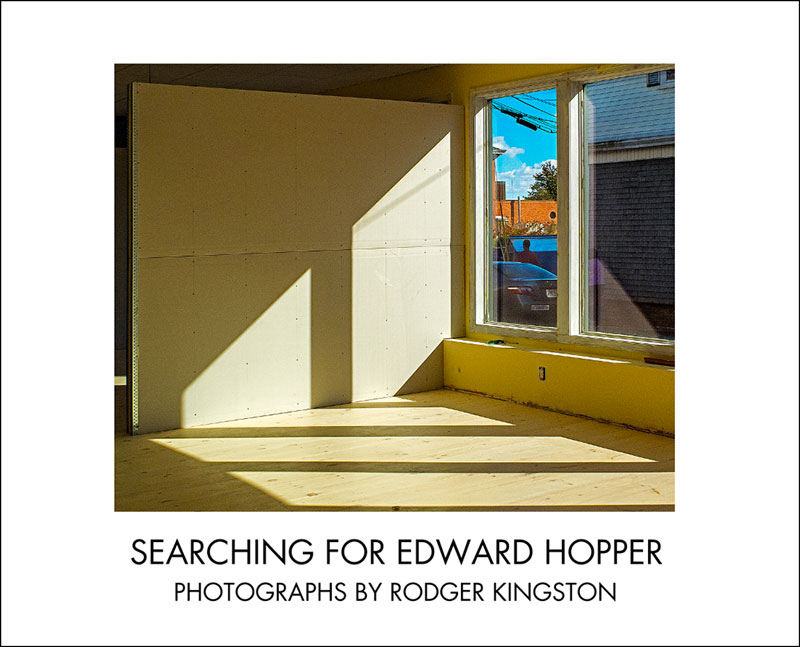

My search for Edward Hopper has been an odyssey across four decades from 1974 to the present, looking for images I made under his influence. Sometimes a particular element in a Hopper painting comes to mind when I’m photographing — the posture of the young woman facing the viewer in Chop Suey when I photographed Jilla, Cambridge, MA 1985, or the slant of light through a window in Rooms by the Sea when I took Sun in an Unfinished Room, Warren, RI 2012. More often the prompt is less specific, subject matter that when seen out of the corner of my eye whispers “Hopper” to me.

Certainly Hopper hasn’t been my only mentor. Charles Sheeler’s clean Precisionist geometry first pointed me in the right direction; discovering Walker Evans extended the possibilities of what a photograph could be.

Stuart Davis showed me the power of graphic elements within a composition. From William Carlos Williams I learned the value of a searching, intelligent eye, and from Walt Whitman, that one could create a whole world between the covers of a book.

No less compelling have been John Coltrane, whose notes are colored by a palate as achingly rich as Hopper’s; and Bruce Springsteen, in whose music is the America of my photographs: colorful, edgy, slightly down at the heels.

But primarily there has always been Edward Hopper, who taught me to see a world simple in subject matter but rich in implication, and the value of pursuing an enduring American vision.

I’ve always favored small cameras; they suit my street-shooting style. During the film years it came down to Leica CL and Contax T and TVS compacts, and now I use a digital Fujifilm X20. This allows me to carry a good camera everywhere I go; after all, the best shots turn up at the damnedest times.

Except for portraits, the subjects of my photographs are always as I find them, never set up or arranged beyond waiting for the light, or for a scene to come together of its own accord. For nearly thirty years I shot color slides and printed them as Cibachromes, and I find that now, in the digital age, I generally still prefer the Cibachrome look, with its dense shadows and heavily saturated colors that seem to have a presence, like paint, on the surface of a print.

I’ve come to particularly value continuity in my work, and I strive to suggest — by choice of subject matter; in a certain consistency of color, tone, and composition; and through the sequencing of my images — the larger reality of a grand continuum. I’m attempting to create a body of work that portrays my era as seamlessly and definitively as Hopper and Evans did theirs.

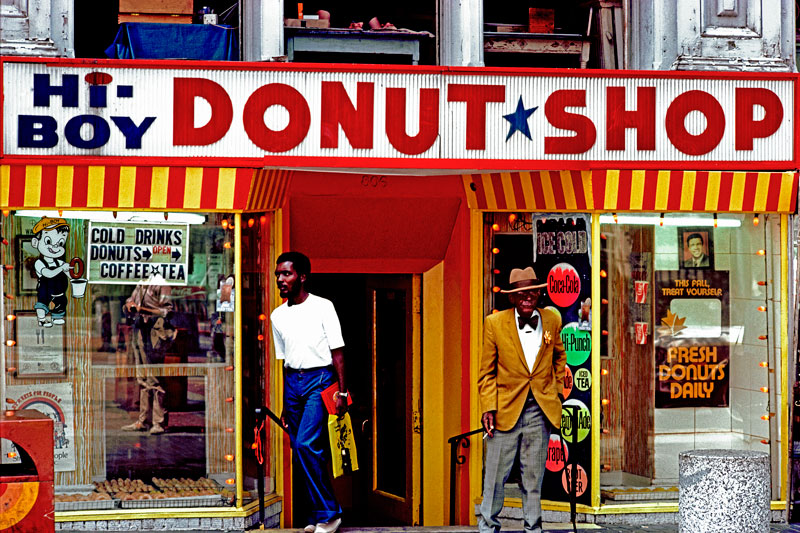

Once in the 1980’s, during a presentation to a museum curator, she exclaimed when I showed her Hi-Boy Donut Shop, Washington, D C, 1979, “Why that’s right outside this building! I’ve walked by there a million times, and never stopped to look at it before.” It was among the several of my prints she selected for their collection, a more than symbolic affirmation for me. People have often told me that they see the world differently after discovering my work—that now they find “Kingstons” everywhere they go. This is very satisfying; it’s when I get reactions like these that I know I’m on the right track.

Searching for Edward Hopper was self-published late in 2014. I put it together using a private gallery on my web site as a light table, then loaded it into the publisher’s software program on my computer. At 188 pages, with 174 full-page illustrations, in hardcover, and printed on premium paper, the book costs me nearly $100 per copy, far too much to sell as a regular trade book. I therefore decided to publish it as a signed and numbered limited edition accompanied by a signed original print, for $350 (less than the regular price of the print alone). This is the second book I’ve published this way, and it really works: in these first few months I’ve sold nearly 25 copies (if that doesn’t seem significant, do the math). I’m currently seeking a publisher to do a trade edition as well. See the book in two page spreads, as published, at my website where it is available for sale.

A well-known writer friend recently wrote to me, “As for the photographs, they are very beautiful and very much in a spirit of Hopper. Thanks for sending them to me. I can’t stop looking at them.” I hope that you can’t stop looking at them either.