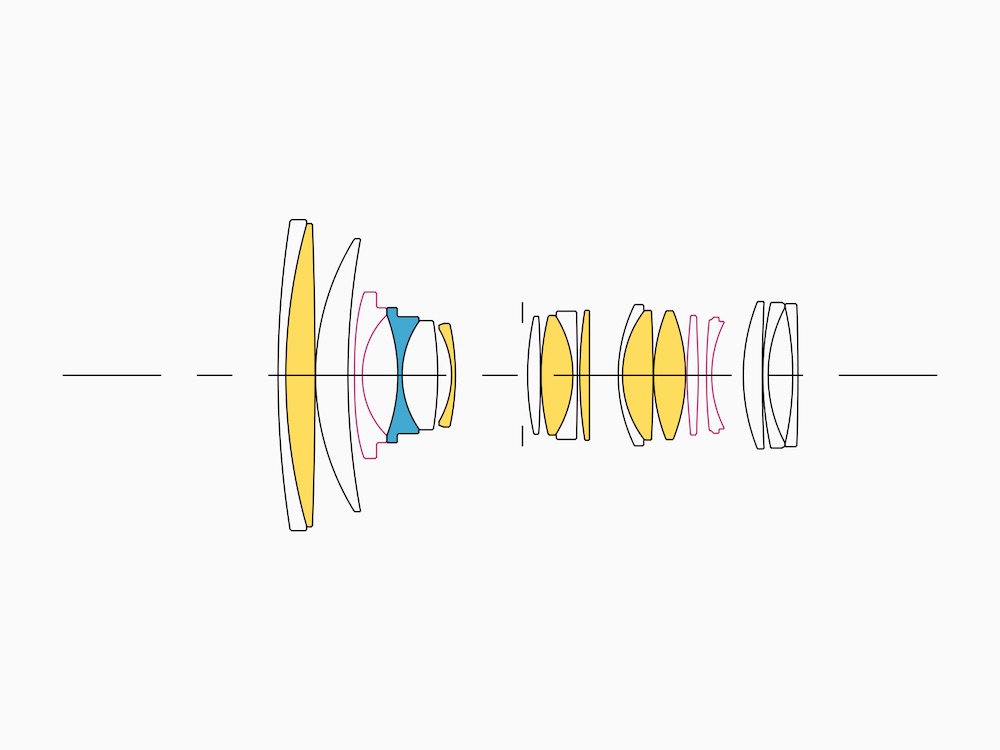

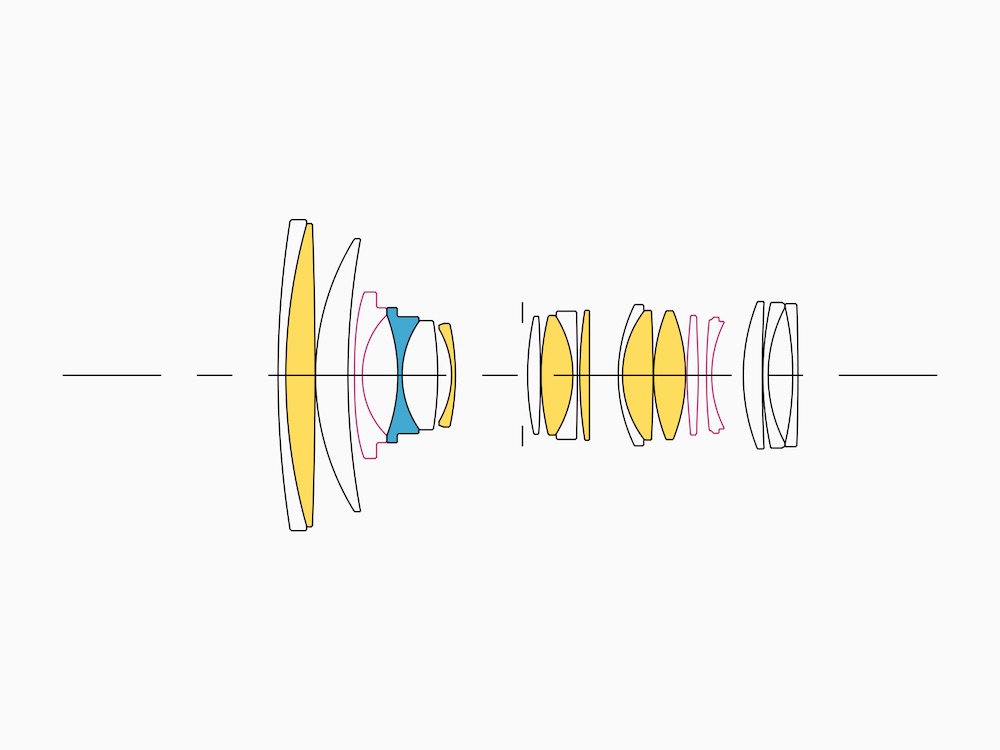

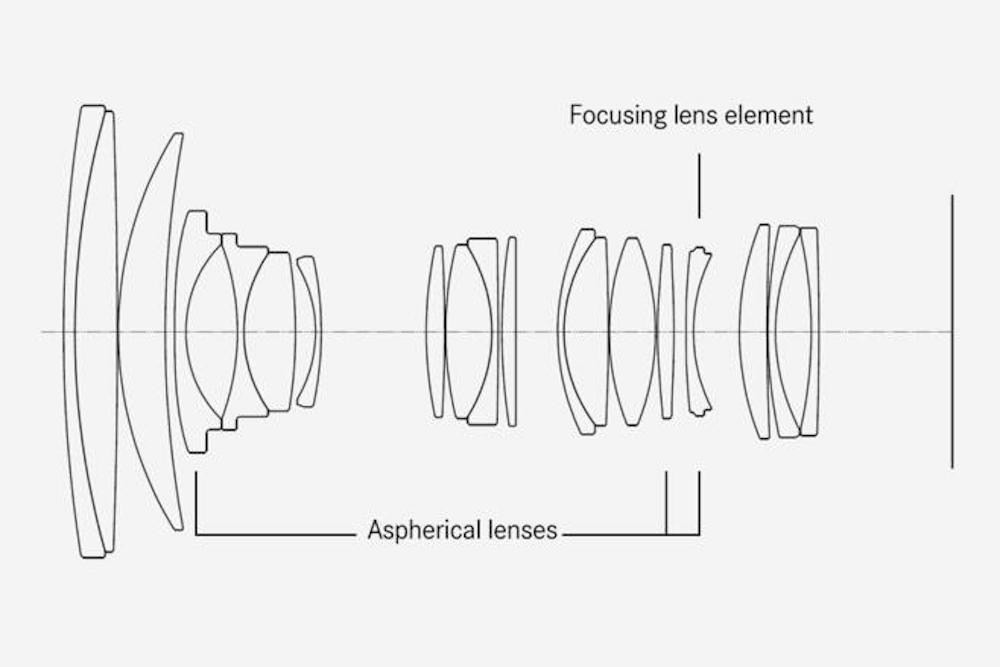

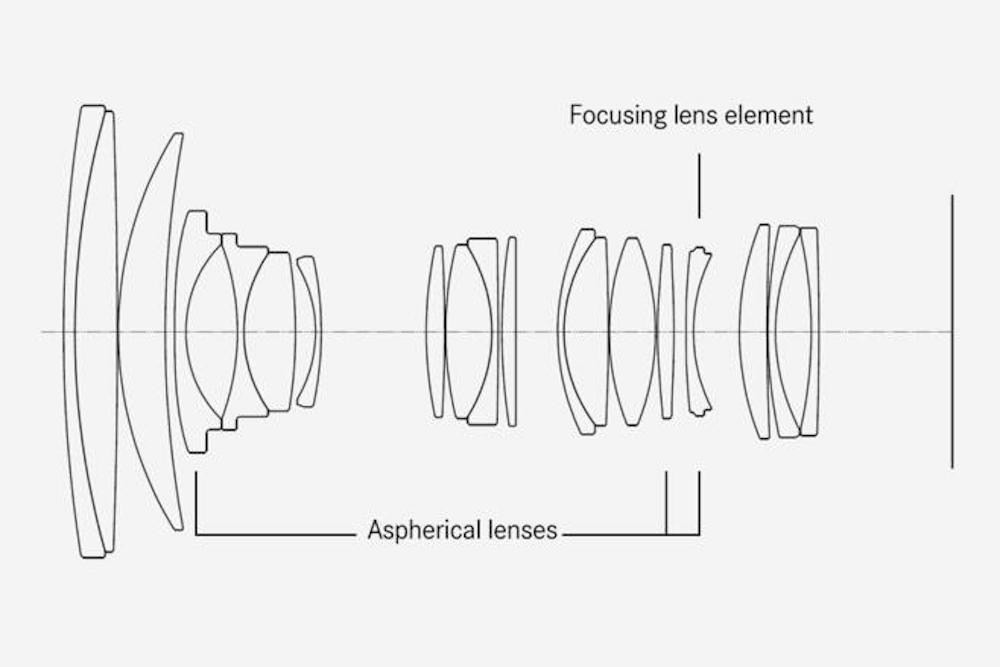

Leica just introduced a new 24-70mm f2.8 Vario-Elmarit for L-mount (or so the press releases say)… I was immediately suspicious that something was not exactly as it seemed, because there are very few Leica lenses one can buy for $2795. A few older M-mount primes with slower maximum apertures are possibilities… Some of the APS-C TL-mount lenses, sure. But a full-frame 24-70mm f2.8 with multiple aspheric and exotic glass elements for L-mount? That should be a $5000 lens… Also, the optical design looked familiar – I thought I’d seen that lens somewhere before. The first lens I checked was the Panasonic 24-70mm for L-mount. Nope, different element count. Then, I saw on another site that the Leica lens might actually be the Sigma 24-70mm f2.8 Art. I didn’t want to simply republish someone else’s tip without checking it out, so I looked at the two design diagrams, which looked incredibly similar (Sigma colors in the low-dispersion glass, providing more information than Leica does , but whatever Leica provides checks out with the Sigma). The size and weight check out – dimensions are nearly identical (within a millimeter), with the Leica a bit heavier (21 grams), but little enough that it could easily be accounted for by a different barrel or focus/zoom rings.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with that Sigma lens – I reviewed it recently in E-mount (Sigma the Lensmaker), and it is my top choice for a standard zoom on E-mount. Sigma is one of the best lensmakers on the planet these days. I haven’t used its competition on L-mount, so I’m not sure how it compares to the Panasonic, or to the $5000+ Leica 24-90mm f2.8-4 (which is made in Germany, so Leica is probably making that one themselves). The only problem with the Leica lens being made by Sigma is that the Sigma version of the SAME LENS costs $1059, and is readily available in L-mount. Even if the “Leica” has a bit of additional ruggedization or sealing (not much, for 21 grams) compared to the already excellent Sigma, it’s not going to outlast TWO Sigma lenses.

Without testing it, the Leica lens earns a Not Recommended, simply because buying the same lens as a tested and Highly Recommended Sigma for less than half the price is a much smarter decision. Most photographers would rather have the 24-70mm f2.8 plus their choice of a Sigma 85mm f1.4, 100-400mm f5-6.3 or 14-24mm f2.8, rather than the 24-70mm f2.8 plus a little red dot sticker – especially because the two lenses are actually cheaper than the lens and the sticker. Sometimes, an optically identical lens in a different barrel can be worth more than twice as much, but those (rare) cases are either full-on cine conversions with very different focusing mechanisms and geared focus, zoom and aperture, or else they’re underwater lenses…

The other recent news item worth mentioning is a couple of new printers from Epson. At first glance, the EcoTank Photo ET-8500 (8.5×11”) and ET-8550 (13×19”) may seem unremarkable. They are 6-ink, dye-based photo printers (that are really 5-ink printers, because two of the 6 inks are Photo Black and Matte Black). They have two remarkable claims, though. First is that Epson claims not to need a Light Magenta or a Light Cyan ink, nor three levels of gray (they use a full black plus one gray, but not two grays). They say that they have enough precision in the head to use variable droplet sizes (5 sizes, with the smallest being 1.5 picoliters) to replace some of the lighter inks. If they pull that off – a 5-color printer that prints like an 8-color printer – it’s a really important innovation. The reason printers run through light inks so fast is that light ink is actually full-strength ink plus distilled water (it’s not less expensive because it contains more water!). If smaller droplets can replace watered inks, it’s a win in both ink cost (less water) and head/printer cost (fewer channels). Of course, these are dye printers – even if the technology works on a dye printer, it’s another step to get similarly small droplets on a pigment printer. The second innovation is that these are EcoTank printers. No whole bunch of 14ml cartridges to replace every 30 prints (yes, some of the 13×19” photo printers are that thirsty)… There are two markets for this kind of printer – one is the photographer who wants to print, but doesn’t want to put the money or space into a big, dedicated photo printer. The second is the photographer who HAS a big, dedicated photo printer, but runs into small jobs that are inconvenient on a roll-fed printer – any kind of cards or promo materials almost require a cutting plotter if printed from the roll, and even then, they aren’t terribly convenient. For the first group, a smaller dye-based printer is a way of testing the waters, and of printing photos on a machine you need anyway – a sheet-fed dye-based photo printer can be a capable home/office printer, and the ET-8500 and 8550 scan and copy as well. For the second group, a secondary photo printer has to be especially economical to run – most of the photo prints you want to run on a small sheet-fed printer are low-value items that don’t need 200 year lifespans, but do need economical running costs.

In both cases, tiny cartridges are a major drawback – and these machines have gone to the other extreme. They use 70ml ink bottles that sell for less than $20 each – which is not only about 1/5 the cost per ml of the usual tiny cartridges, it’s actually cheaper than ink for big roll-fed photo printers. The printers themselves are on the expensive side ($599 for the 8.5×11” ET-8500, $699 for the 13×19” ET-8550) – but not by much if Epson’s boasts of photo quality equivalent to an 8-color printer are accurate. Their closest competitor is Canon’s 8-color, dye-based Pro-200. Canon’s printer is $599 for a 13×19” model, but it uses 12.6 ml cartridges (and it doesn’t scan or copy). If the print quality really is equivalent, the Epson will pay off the difference in the first ink change.

The ET-8550 is coming for review – look for a first report in June, and more on it in late August or September.

There are a group of cameras in for review right now that share a common characteristic. I presently have no less than four cameras (including my personal Sony A7r IV, which is part of the test) in my possession that use the same underlying image sensor technology. From the APS-C Fujifilm X-T4 to the medium format GFX 100S, they share the same pixel design, and it is one of the best designs currently available – the Sony 3.76 µm Exmor. This is a thoroughly modern pixel, using copper wiring and backside illumination, and it is consistently a high performer, ranking near the top in tests of color accuracy, noise and dynamic range. It is not a stacked sensor, an even newer design that emphasizes speed, found in Sony’s A9, A9 II and A1, Canon’s and Nikon’s upcoming pro sports bodies (EOS-R3 and Z9) and most modern cell phones.

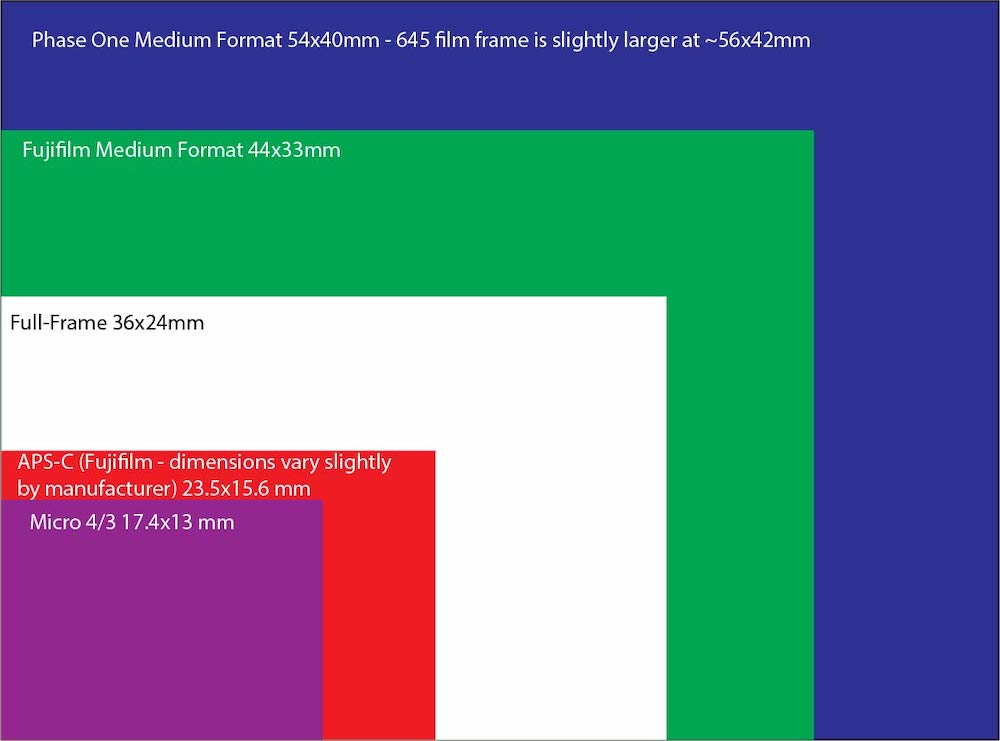

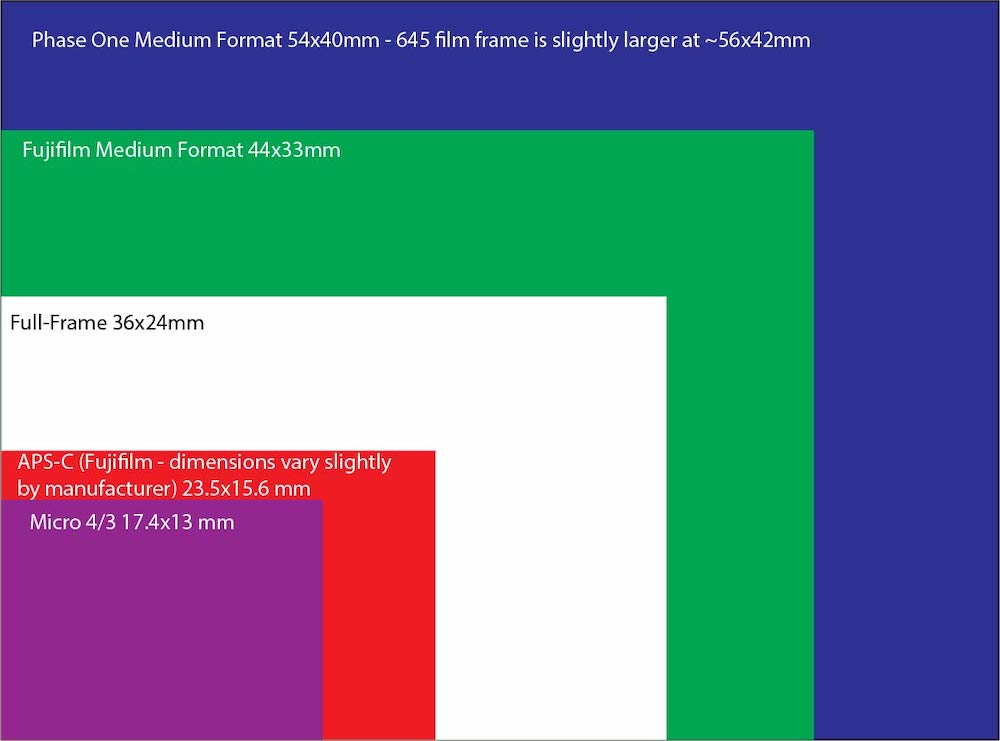

This sensor design was introduced in 2018, almost simultaneously on the 26 MP 23.5×15.6mm (APS-C) Fujifilm X-T3 and the 150 MP 54x40mm (medium format – close to 645 film) Phase One IQ4 150, and it has a unique feature. The sensor on the Phase One, while of the same basic design as the Fujifilm, is almost six times the physical size and, since the pixels are the same, also six times the resolution. The sensor has just over 70,000 pixels per square millimeter, no matter how many square millimeters of it a given camera has. In 2019, we saw two additional sizes of the same sensor – the 61 MP 24x36mm (full frame) sensor in the Sony A7r IV (and now the Sigma fp L) and the 102 MP 33x44mm (small medium format) sensor in the Fujifilm GFX 100 and 100S. One basic sensor design, four sizes…

It surprises me a bit that Sony doesn’t also make a Micro 4/3 version of this sensor. It would be almost exactly 16 megapixels, so a slight downgrade in resolution from the 20 MP Same Old Sensor, but it is a much higher performance platform in every other way. It would be well worth the resolution tradeoff to pick up an extra stop or more of low ISO dynamic range and four years of improvement in noise performance. Even without a Micro 4/3 version in existence, essentially the same sensor coming in this range of sizes offers a chance to look at what a bigger, higher resolution sensor really means without having to contend with differences in sensor age, performance or design.

Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple. The underlying sensor is the same, but manufacturers specify their own sensor “toppings”, and the only mainstream manufacturer to use the 26 mp APS-C version is Fujifilm, which means that one camera is going to be X-Trans – Fujifilm doesn’t use the 26 MP sensor on any of their low-end cameras with conventional Bayer filtration, and, even if they did, those cameras have anti-aliasing filters, which none of the others do (and which is probably a bigger difference than X-Trans vs. Bayer). For some reason, Sony has never put their best APS-C sensor in any of their own cameras. Its only non-Fujifilm appearance is in the Pentax K3 mk III, which is both brand-new (and hard to get a sample of) and hardly a mainstream camera. There are other differences among manufacturers as well – Fujifilm and Sony take different approaches to color. Any comparison like this needs to look at processed images for the most part – nobody’s going to use a GFX 100S for out-of-camera JPEGs (although you actually could – it has a very good JPEG engine). I am going to try to compensate for color differences in the raw processing as best I can.

I have the Sony 3.76 µm sensor in for testing in four bodies, but only three sensor sizes (I am missing the ultra-exotic Phase One IQ4 150). I have two Fujis (X-T4 and GFX 100S), one Sony and the unusual Sigma fp L, which shares the A7r IV sensor (or a very close relative). The two Fujis and the Sony are all relatively conventional designs (at least as far as the term “conventional” can apply to the highest resolution one-piece camera ever made). Apart from the IQ4, which is much more expensive per pixel, but is also essentially handmade, the various sizes are pretty much “priced per pixel” – the GFX 100S ($6000) is almost four times as expensive as the X-T4 ($1699), but it has almost four times the resolution. The A7r IV is somewhere right in the middle – depending on specials at any given moment, it ranges from $3000 to $3500, and its resolution is 60% of the GFX’s and a little over twice that of the X-T4. The Sigma looks cheaper than the Sony, but once the accessories are included, it’s very comparable.

The other issue is, of course, that there are four different lens mounts and three different formats here. There is no way to get the same lens on everything, especially trying to match fields of view, and the best way to get similar lenses is beyond my resources. The absolutely ideal test (assuming an Otus 100 will cover 33x44mm) would involve a 100mm Zeiss Otus on the GFX, 85mm on the Sony and 55mm on the X-T4. They all have very similar fields of view – but I have neither three Otii lying around, nor the high-quality adapters to connect them to the bodies.

My compromise (since it would be very hard to match fields of view with prime lenses) is to use high-quality f4 zooms on all three bodies, which have a significant range of overlapping focal lengths. The Sony has the 24-105mm f4, while the GFX has the 32-64mm f4 and the X-T4 is sporting the 16-80mm f4. All three lenses start close to 24mm equivalent, and all cover through 50mm equivalent – although the two smaller formats have quite a bit of additional range at the long end. The GFX has a slight advantage due to its less ambitious zoom range, and this is noted, but inevitable. The GFX is also a slightly squarer format than the other two cameras – again, noted…

The Phase One IQ4 150 that would be the logical final piece on this ladder of Sony sensors is a completely different type of camera, and it is priced on a different scale. Depending on whether you have an existing back to trade in, and what type of camera you want to fit to the back, it is in the range of $25,000-$50,000 for back and camera (although it is often leased) for 1.5x the number of pixels of the GFX. The very large sensor may be more difficult to manufacture, production runs are extremely short, and the filtration over the sensor may well be extremely high-end (and is almost certainly also expensive due to custom manufacture).

The Phase One XF camera body and back combination is exactly twice the weight of the Fujifilm, it’s not weather sealed, and it has comparatively (extremely) primitive autofocus and no image stabilization. I’ve never used an IQ4 back, but I have shot an older back briefly on the XF body, and it has two drawbacks for landscape use in the field. It is a huge, heavy camera – another comparison is that, with an 80mm lens on both, it’s very close to twice the weight of an old Hasselblad with a waistlevel finder. All medium format SLRs with prisms are very heavy. The XF is nothing exceptional in that category – a prism notoriously made the otherwise compact Hasselblad a beast to handle, especially if you also added a winder. It also has the worst mirror slap I’ve ever personally seen. I have used 500-series Hasselblads extensively, and a Mamiya RB 67 a bit, but never a Pentax 67, so the real mirror slap champ is outside my experience. Neither the Hassy nor the RB have instant-return mirrors, and my only experience with motorized medium format SLRs is those few shots on an XF. Maybe anything with an instant-return mirror that big has a lot of mirror slap? Most cameras with mirror slap vibrate a bit – the XF actually recoils. Best used on a tripod with mirror lockup!

The other option is to mount the back to a technical camera, either Phase One’s own XT or one of a number of third-party options. A technical camera pretty much requires a tripod for every shot, but it offers flexibility that nothing else short of a true view camera can match, and it can be much more compact than a medium format SLR.. All technical cameras offer rise, fall and shift (vertical and horizontal movements where the lens and back remain parallel). Most allow combinations of these movements, but some only allow one axis at a time. Some (generally larger) cameras use a view camera style bellows to permit tilt and occasionally swing (vertical and horizontal movements where the lens is on an angle to the back) to correct the plane of focus. Is a “technical camera with tilt” really a highly capable technical camera or a small view camera meant for medium format backs instead of large format film holders? It’s a question of definition… There are also technical camera (and view camera) adapters available for mirrorless cameras from APS-C to medium format, but they have a major drawback – since you’re essentially stacking two cameras one in front of the other, the distance from the lens to the sensor is very long, and wide-angle lenses won’t focus to infinity. Using a back, which adds almost no focal distance of its own, eliminates that problem.

A back and a technical camera can be a very rewarding way of shooting slow-paced landscape, and is something I hope to try out. Unfortunately, there is no generally available back right now that uses the GFX 100S sensor (there is one made exclusively for aerial photography), which could offer a very capable sensor at a somewhat affordable price. The three current sensor options (there are many more if you include the used market) are the 50MP sensor that is shared with the GFX 50S and 50R, a 100 MP 645-size sensor and the 150 MP sensor at the top end. All are CMOS sensors similar to what’s in any modern DSLR or mirrorless camera, with the 50 and 100 MP options being a generation or two older technology, while the 150 MP is the largest version of the new sensor in this test (although I couldn’t borrow one anywhere). The 100 and 150 MP sensors are both essentially the size of 645 film – one size larger than the 33x44mm GFX/X1D/Pentax 645 sensor size. All CMOS backs under $15,000 use the older 33x44mm 50 MP sensor that is also found in every one-piece medium format camera except the GFX 100/100S. Another option would be a used CCD back – image quality can be exceptional at very low ISO, but even the most recent CCD backs don’t comfortably go much above ISO 100, and live view is very slow if it exists at all (a special problem for a tech camera).

Perhaps the most initially exciting camera in this group is the GFX 100S. The original GFX 100 produced stunning files, but it was quite a difficult camera to use. It was the only Fujifilm camera whose controls I’ve ever found counterintuitive, and it was big and bulky with poor grips and handling. What a difference a generation makes. After one day of shooting, the 100S is among my favorite cameras I’ve ever handled. Without reading the manual (I did, but after my first shooting day), I have it configured in aperture priority (a matter of rotating the mode dial to a clearly marked “A” position) with aperture on the lens ring, ISO on one dial and exposure compensation on another. The “exposure triangle” for raw files…

It is about the size of something like a Nikon D850, although it’s actually somewhat lighter. It’s bigger and heavier than most full-frame mirrorless cameras, although not by a whole lot (they’re around 700 grams, and the GFX is 900 grams), and it’s lighter than the dual-grip Olympus E-M1x (and almost certainly lighter than any mirrorless camera with a battery grip attached), The 32-64mm f4 lens I have with it is about the size and weight of a typical mirrorless 24-70mm f2.8 – somewhat lighter than an equivalent DSLR lens. For about 10% more size and weight than a Sony A7r IV, Nikon Z7 II or Canon EOS-R5 with a 24-70mm f2.8 and for slightly less weight than a full-frame DSLR with a 24-70mm f2.8, the GFX100S with the 32-64mm offers somewhat less zoom range, mainly at the telephoto end, but over 100 megapixels worth of one of the best sensors there is. The shallow depth of field capability of the f4 lens on medium format is very close to that of the f2.8 lens on full-frame, so the real difference is the range between 50mm and 70mm equivalent focal length.

Another way to put it is that it’s about as heavy as a top APS-C kit with one extra lens. It’s about midway between the weight of an X-T4 with the 16-80mm f4 and 10-24mm f4 and the weight of the same X-T4 with the 16-55mm f2.8 and 8-16mm f2.8. Pick one lens at f2.8 and the other at f4, and you’re within about 100 grams of the GFX kit either way. With two f4 lenses, you could have a Z7 II with the 14-30mm and 24-70mm f4 lenses in the same weight profile. Neither Sony nor Canon offers a modern, high-quality 24-70mm f4 lens (the old 24-70mm f4 “Zeiss” will embarrass itself on an A7r IV – a new 24-70mm f4 G is one of my top two Sony lens requests), so the full-frame kit that goes much wider is only an option for Nikon shooters.

It fits in a relatively small camera bag –I have the 100S with the 32-64mm lens in a MindShift MultiMount 20, with plenty of room to put a couple of batteries in the lid compartment. I hike with that bag in addition to my full backpack all the time. Try squeezing an 8×10” Deardorff into a modestly sized holster case, let alone its tripod…

The GFX 100S is one of the most comfortable cameras I’ve used in the hand. For my larger than average hands, the grip feels just right, and the control dials and joystick are almost perfectly positioned. This is as nice a grip as any camera on the market – think really good DSLR, or perhaps Nikon Z but a bit larger. A photographer with small hands may find it uncomfortable – if a standard-sized single-grip DSLR like a D850 or EOS 5D mk IV is uncomfortably large for you, the GFX may be as well.

It has relatively simple controls – two dials, an excellent joystick (the best I’ve used), a mode knob, AF mode and still/movie switches and the like, and a few (mostly unmarked and highly customizable) buttons. The menus are typical Fujifilm – much better than, say, an older Sony, but not as clear as Nikon or the very latest Sonys. A lot of photographers love Canon menus, but not having experience with recent Canons, I can’t say.

This is not the X-series control scheme with a million marked dials – rather, it’s a very clean interpretation of “modern DSLR”, as good as anything Canon or Nikon has done. Unlike a Sony or an X-series Fujifilm, you won’t find a dedicated exposure compensation dial or an ISO dial, but every lens has an aperture ring (and Fujifilm aperture rings are about the best around), restoring the lost control point. Even in full manual mode, you have enough dials for ISO (exposure compensation makes no sense in full manual). The one place you are short a dial is in shutter priority, since shutter speed takes up one dial, and ISO and exposure compensation have to share the other one. Exposure compensation always requires a button push – I wish there was a way to assign it to a dial with no button. The best you can do is set the button push to the rear dial (so it becomes a push and turn on the same control).

One notable omission is that there is no four-way button controller or jog dial surrounding it – between the excellent 8-way joystick and the number of customizable buttons, it’s not really necessary, but it’s so standard that its omission is going to throw people at first. You navigate the menus with the joystick, and there’s an OK button and a back button (or you can use the touch screen, which I always forget exists, since I never use touch menus on any camera – merely personal taste). One significant addition to the interface is the customizability of the large, high-resolution screen on the top plate. It can show a standard (and quite complete) set of shooting information, but it can also show either a graphical representation of what the dials are set to or a histogram. Having a histogram on the secondary display is a relatively standard medium-format feature, actually pioneered by the old Rollei Hy6 and available on modern Hasselblad H-series (not the compact H1D series) and Phase One bodies, but it’s almost (if not entirely) unheard of outside of medium format.

The GFX 100S is not, by any rational standards, a slow camera, but it is also not a fast one (and most modern cameras are fast). It is capable of 5 frames per second in certain modes, with continuous autofocus – but why would you use this particular camera in that way? Top speed equivalent to a low-end Rebel is not why you buy a $6000 camera with a laser focus on image quality. This is a camera that cries out to be shot in single shot mode, not any form of continuous drive. The enormous resolution begs for contemplation.

Its autofocus speed is entirely adequate, and it would have been considered quick not many years ago (it is a similar system to the X-T4, although some of the bigger, heavier lenses aren’t quite as snappy as the lighter XF lenses). Until the GFX series, all medium format cameras had only primitive center-point autofocus (the Pentax 645 series had a bunch of focus sensors all concentrated in the center of the frame, because they were using APS-C focus sensors on a medium format camera, and Phase One’s “Honeybee” system is similar – it’s multipoint (although not selectable multipoint as far as I know), but it only covers a small portion of the frame).

The GFX 100S will focus almost anywhere in the frame, since it uses an on-sensor combined phase-detection and contrast-detection system. It is slower than most modern DSLRs and top-end mirrorless cameras below medium format, but it is MUCH faster and more flexible than any non-Fujifilm medium format camera. It has far better autofocus, and is far faster, than any large format view camera, which is what its image quality is similar to – of course, view cameras don’t HAVE autofocus, and they shoot at most a frame or two per minute, depending on how good you are at changing film holders. If you are looking for a convenience-focused camera for snapshooting, first of all, why spend $6000, and secondly, almost any modern full-frame or APS-C body will serve you better.

If you are looking for ultimate image quality, though, there is nothing better (with two possible minor exceptions – one is the very rare and expensive Phase One IQ4 150, and the other is 8×10” film). Real evaluation of file quality will, of course, require prints, and there will be plenty of prints on a variety of printers in the full review, the next article about these cameras. Looking at the first day worth of images on screen, my response is that I have never seen any digital file that looks like this before, and I’ve never seen a film scan that looks this good either (I’ve seen up to drum-scanned 4×5”, but not 8×10”, and the GFX clearly outclasses 4×5” Velvia). Since I’m on the road, I haven’t had them up on my calibrated EIZO CS2740 – these results are only from preliminary looks on my MacBook Pro’s screen.

Fujifilm technical expert Justin Stalley told me to be prepared for about as much difference between high-resolution full-frame and GFX 100S files as between really good APS-C and high-resolution full-frame. I was initially skeptical – high-resolution full-frame is already so good that I questioned whether there was another jump like that available. What I’m seeing on the screen indicates that there IS another jump like that available. The question is whether it’s printable with any of today’s printers, and, if so, what size print, and what technology, will be needed to see those results. The full review coming in June will include a close look at this question, because the reason to use a camera like this is to put fine prints on the wall.

One decision I need to criticize Fujifilm (and Sigma, who did the same thing) about on a very thoughtfully designed camera is that they do not provide a battery charger in the box. This is a $6000 camera that will be used heavily, and it only shares its battery with one other camera (so most users won’t already have a drawer full of chargers). I can see two reasons not to provide a charger with any given camera, and neither one applies here. One is that it uses a very common battery, and the correct charger has been around forever, therefore most buyers have one (or perhaps 17). I’m thinking Nikon EN-EL 15, Canon LP-E6, Sony NP-FZ100, and Fujifilm NP-W126/126S (maybe one or two others, like the big sports camera batteries for Canon and Nikon)… This is especially true of expensive or specialized cameras unlikely to be bought by newcomers to the brand. Most X-Pro 3 buyers, for example, would rather get two batteries in the box than one and a charger, since they’re almost certain to own another Fujifilm camera that uses the same venerable NP-W 126S battery. The second is that sub-$500 cameras are likely not to get charged as frequently, and the charger might get lost, so USB is a better option at the lowest end…

Neither one applies here – the NP-W235 is a brand-new battery shared only with the X-T4 (so far), and the GFX 100S is a very expensive, professional camera. The X-T4 ALSO doesn’t come with a battery charger – there’s no way to acquire one packaged with a camera… In-camera USB charging is a nice emergency backup, but it’s not the right way to charge everyday – if nothing else, USB ports are notoriously fragile, and why risk an expensive repair on an expensive camera when a battery charger does the same job better. The battery charger Fujifilm sells is a nice one – two bays, a screen and USB powered, but it needs to come with the camera… One possibility camera makers might explore is not to have the charger literally in the box, but have expensive cameras come with the buyer’s choice of two batteries OR one battery and a charger (one battery in the box , and either a spare or a charger is included with purchase). Please have the dealer fulfiil this – no “mail in a coupon and charge your battery six months later”.

I count nine rotary controllers (one command dial, three knobs, four rotary switches and the diopter adjust, which is sort of cheating because it isn’t electronic) on the front and top of the body in this image, plus there’s another command dial in back…

The Fujifilm X-T4 is probably the best APS-C camera on the market, and, short of printing really big, it may be the best all-around camera on the market. It’s not the best at any one thing, but it is a very appealing package – great lenses, compact body with excellent controls, very good image quality, very good autofocus, very good video. If you add one thing (say resolution and a larger sensor), other things start to go in the wrong direction (lens size and weight). If you want better autofocus, you can have it, but will the body feel be as good? The X-T4 is not a specialist sports and action camera, nor is it a specialist pixel monster, nor is it a specialist video camera – but it’s a better sports camera than any pixel monster, a better camera to print big than any sports camera that isn’t three or four times as expensive, and a better video camera than most of the sports cameras AND most of the pixel monsters.

There may now be a better generalist camera – but it’s a LOT more money, and it’s going to be quite a bit heavier, especially with lenses. The new Sony A1 is probably the X-T4’s closest competitor, and it is probably better at everything. Where the Fujifilm has a very good AF system, the A1’s might be the best in the world, especially with its rock-solid focus tracking. Where the Fujifilm offers 26 megapixels of very good image quality, the A1 offers 50 megapixels – I haven’t used one yet, but those who have say it’s superb. Where the Fujifilm offers very good 400 Mbps 4K60p video, the A1 ups the ante with 4K120p and 8K30p.

With the A1 around, why is the X-T4 still a contender for best all-around camera? The A1 body is four times the price of an X-T4, the lenses average about 1.5x the price of equal-quality Fujinons (there are bargains and overpriced lenses in both systems, but that’s an average), and the weight of a system is about 1.5x as great (mostly in lens weight). If you don’t need 50 MP or 8K, why pay the price of entry? Any Sony more comparable to the Fuji’s price will have advantages and disadvantages – you can get more pixels, but you’ll lose some of the video aplomb, or you can get a faster focusing camera, but it won’t be as nice a body to use… In any case, you’re into heavier lenses. A Nikon Z5 or Z6 II is another competitor – the Z5 is similarly priced and full-frame, but not anywhere near as good a video camera, nor as fast for action. A Z6 II can do most of what the X-T4 can do, and it’s full-frame – but it’s considerably more money with comparable lenses, and the lens lineup (while growing) is heavier and not as complete.

The Sigma fp L, in many ways, has as much in common with the Phase One back as it does with the conventional cameras – it’s somewhere right in between a one-piece camera and a back. It’s incredibly compact – no larger than many Micro 4/3 cameras, but it’s got a 61 MP full-frame sensor. In order to get it as compact as it is, Sigma stripped essentially everything that didn’t absolutely have to be there off the camera. Yes, you can technically shoot with the Sigma after attaching a lens and putting a battery and a memory card in it – but you’ll have no viewfinder other than the screen, no hotshoe and no grip. It does have a shutter button (although it doesn’t really have a shutter – read on), a couple of control dials and several more buttons. The default means of viewing is a nice but non-articulated rear LCD, and Sigma offers three different viewing options for when the screen is not enough.

The most conventional choice is an auxiliary electronic viewfinder that attaches to the left side, putting the viewfinder in the classic Leica M position. It’s a nice finder – the 3.68 million dot unit that appears on a lot of cameras with decent optics, and, in a very rare feature for a still camera, the finder tilts (even though the screen does not). As far as I know, the only other tilt finder on a still camera in recent years is the one on the GFX 50S and original GFX 100 (which needs an extra-cost adapter to tilt). There are a couple of drawbacks to the electronic viewfinder. One is that, while Sigma claims robust weather sealing for the camera itself, and many L-mount lenses (including quite a few of Sigma’s own) are also well sealed, the finder is not sealed. The second drawback is that, while the finder is very lightweight, it adds enough width to the camera that the combination is substantially wider than a Leica or most rangefinder-style cameras (it’s not wider than any of the various Texas Leicas (Mamiya and Fujifilm medium-format rangefinders – usually film, but the GFX 50R is at least an Oklahoma Leica…)), and the part of the camera your face is pressed against is not technically part of the camera… The Sigma itself is only 113mm wide, but the viewfinder adds nearly 45mm for a total width of 157mm, while a Leica M10 is 139mm wide, a Fujifilm X-E4 is 121mm and a Sony a6600 is 120mm wide. It’s almost as wide as a Fujifilm GFX 50R (161mm). From an hour or so of playing around, it’s an awkward hold to have a camera this wide and this light, especially with a joint between the body and the finder (although the tilt finder is really nice).

The other two viewing options are both optical. Sigma makes a Hoodman-style loupe for the rear LCD that permits viewing in a wide range of conditions. It’s no bulkier than any other similar loupe, but it’s no less bulky, either. The camera and loupe combine to be heavier and bulkier than an A7r IV, but much less heavy and bulky than the Sony with a similar loupe. Sigma also includes a hotshoe adapter with the camera, and any optical viewfinder of the photographer’s choice could go in the shoe. Sigma themselves make an optical viewfinder (originally made for the dp-2 Quattro) that is closely matched to their very compact 45mm f2.8 lens, and there are a huge range of finders available from other companies, from inexpensive “junk” optics to incredibly expensive Leica finders. Of course, any finder in the shoe is going to have parallax at close distances – it’s offset from the lens in two directions, and it is not coupled to the camera in any way, so it has no idea where the lens is pointing. With a very wide angle lens, the parallax isn’t worth worrying about except at very close distances, while it’s nearly impossible to sight a long telephoto using a finder that doesn’t see what the lens is seeing. There is a thoughtfully designed small grip accessory (Sigma HG-11) that really doesn’t weigh anything. It should be included with the camera, although it makes sense to have it detachable in order to make the camera easier to rig in video cages, drones or anything else. The $58 grip should be considered an essential part of the camera if you ever intend to shoot it handheld.

Another thoughtful accessory is the new Sigma BC-71 battery charger (again, it doesn’t come with the camera, but it should – see commentary directed at Fujifilm above – et tu, Sigma…). While most chargers supplied by camera manufacturers are much larger than they need to be and AC power only, the little BC-71 is absolutely tiny and USB powered. It’s half the size of the Nitecore USB chargers I use for most cameras (although it’s a single-bay charger and the Nitecores are dual-bay). Since it’s USB-powered, it’s easy to power from any source – wall, car or portable battery pack. Sigma also makes the BC-51, which is cheaper, but falls in the category of “uninspired camera manufacturer chargers”.

The BC-71 is priced at $95, which is absurd even for a charger as thoughtfully designed as this one (the Nitecores are around $30, although they don’t include a USB wall adapter, which the BC-71 does). Most of us have plenty of USB wall adapters, and Sigma’s is nothing special, although it’s a bit more powerful than most USB-A adapters – it’s 1.8 amps, (about 8 or 9 watts), while most are more like 5 watts. Neither the adapter nor the charger itself is USB-C (the charger is Micro USB), which is a shame from a standardization viewpoint – although the battery is small enough that I wouldn’t want to charge it with much more than 8-9 watts, so the fact that it doesn’t have USB-C’s high power isn’t really a disadvantage.

The remarkable thing about the fp L is its tiny size and light weight. With the smallest possible lens (Sigma’s own 24mm f3.5 or 45mm f2.8 are about the lightest decent L-mount lenses), it’s possible to get it under 1.5 lbs ready to shoot, and there are plenty of sub-2 lb choices. A 61 mp full-frame sensor in such a package is little short of remarkable (it takes careful lens selection to get an A7r IV much under 3 lbs, and under 2.5 is very tough). That makes a huge difference in getting the camera into unusual places. While the Sigma won’t quite fly on a consumer drone, it will certainly take much less power than lifting something like the Sony. If you’re using it on a gimbal, the Sigma will probably require one gimbal size less than the Sony. It can sit on a lighter tripod, or be attached to a lighter boom. Of course you give up some features for a camera this small and light. In addition to the previously mentioned quirks, the Sigma is electronic shutter only. It will show banding with flickering lights, and its flash sync speed is a pitiful 1/15 second. Even a Pentax 67 (perhaps the most annoying camera in history to sync with flash) at least offered 1/30 second! Most photographers have never used any camera with a sync speed slower than 1/90 or so, and most DSLRs and mirrorless cameras are 1/200, 1/250 or even 1/400 in the new Sony A1. The other big drawback is that the camera doesn’t have in-body image stabilization, and because most L-mount lenses aren’t stabilized either, there are an awful lot of unstabilized combinations. A real shame on a camera that just begs to be used handheld.

These cameras (and my old friend the A7r IV) are the contenders in a group test in a variety of National Parks over the next couple of weeks, and finishing up in Harvard Square, perhaps the best source of relatively interesting brick walls in the United States… The real star, though, is the Sony 3.76 µm sensor in all of its guises. I’ll be doing my best to match the conditions, in order to look as closely as possible at the effects of sensor size and resolution in the print. I’ll also be shooting for art with all of these cameras, to see how they perform outside of test conditions. The first few shots with the GFX 100S are extremely promising.

Dan Wells

May 2021