Richard Owens is a Canadian artist, born in Montreal and working now in Toronto.

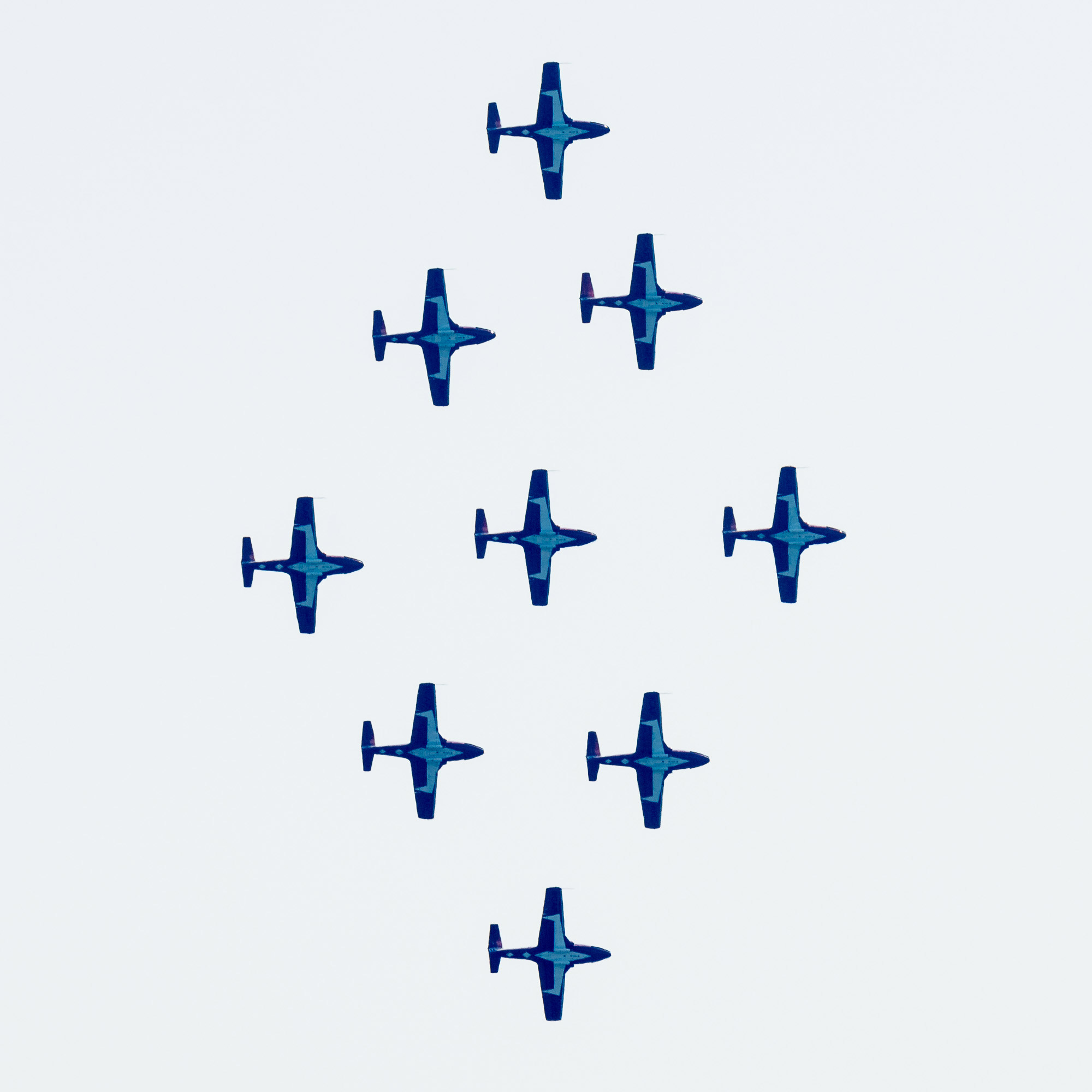

His unusual photography consists of mysterious psychological mindscapes cast in miniature, a project he started 7 years ago.

But although unusual, his work can be located within photographic tradition. It is broadly pictorialist, entailing the construction of evocative scenes—scenes such as a Jeff Wall or a Gregory Crewdson might make, or even the much earlier William Mortensen—albeit, smaller. And in the tradition of miniatures there is David Levinthal’s large body of varied miniatures work; Laurie Simmons’s evocative and subtly lit scenes of female domesticity; and the politically charged Diableries from the 19th century.

“When I began this work I obsessed with miniatures as a medium of expression—a medium that is highly controllable. Unlike real models, mine don’t need to be flattered or fed or given breaks—they don’t even move once the right position is found. They stay still while I can work on other aspects of the set (except for the unfortunate tendency of little things to fall over). And I love that my subjects are essentially playthings which, I think, is disarming for the viewer.”

Yet, his work does not belong with most miniature photography, which tends to document completed miniature creations. For Owens, the miniature is never a finished thing, it is made only to present a convincing face to the camera and then be disassembled.

Owens’s work is deeply psychological. “I learned to look inward. My ideas often arise as complete visions, visions that I feel compelled to bring to light. I try not to analyze them as I work on embodying them, but to preserve their mystery. Embodiment means play and experimentation—play with figures, materials, wardrobe, sculptural settings, backgrounds, lighting. But time and again, especially with the earlier images, I had to learn what would work not only as a miniature, but for the camera.”

Still, Owens does try to nurture the creative process. “Opportunistically, I’ve collected a wide array of architectural modelling figures and props, model railway figures and materials, doll house furniture and other miniatures. I thought having this collection, playing with it and combining elements, would provoke new ideas. It does to some extent: however, I mostly find myself sourcing anew the figures and materials needed to correspond with my latest vision. They seem rarely to be in my inventory.“

Owens seems to mean “vision” at least semi-literally—that his new subjects present themselves in his mind’s eye. In that sense they are a “vision” and he is driven to make them real.

But there is also something visionary about his work, a concept captured by photography writer and critic Vicki Goldberg in her essay on Josef Koudelka:

“Styles are not entirely easy to come by, but a clever photographer can find one without twisting his soul for it. A vision is more difficult and more rare. Style depends largely on surface components such as composition and contrast, on aesthetics, on a consistent eye, sometimes on gimmicks. Vision probably draws as much from the life as from the eye, from the heart as well as the brain, from the complexities of personality more than from ingenuity or mastery of craft.”

Owens’s work is more defined by vision than style. His approach, while still speaking to a narrow photographic tradition, is idiosyncratic and even strange. Strange, and yet not so much so that a viewer does not find the shock of self-recognition in it.

Owens’s dreamlike images are freighted with symbolism. Owens, who is also a poet, thinks of them as visual poems, works that yield, like a poem, to structural analysis and symbolic interpretation. Much of the inspiration and vocabulary for his work is influenced by modern poetry, notably the densely imagistic work of Wallace Stevens, who championed the power of the imagination and its creation of meaning for the world.

Technical Aspects

Owens photographed his first miniatures with a Pentax 645z (acquired, as it happened, on the advice of Michael Reichman, who founded Luminous Landscape). However, the limitations of the SLR format, even with specialized tilt/shift and macro lenses, fast became evident. Owens switched to a Sinar P monorail view camera with a Fujifilm 50 megapixel GFX medium format body as a digital back and a Rodenstock 210mm f5.6 lens. He finds the extreme tilts and shifts of the Sinar essential to work within the very limited depth of field of miniature photography—for thematic emphasis as well as precise detail.

The final product is a framed print, usually 430x560mm (17×22 inches) on Canon Premium Fine Art Smooth paper, printed on a Canon Pro 1000 printer. Images are made in camera and postproduction work is minimal.

Owens plans to explore even larger prints and perhaps backlit transparencies. The impact of the miniature is increased by taking it out of its small scale and confronting the viewer with an anomalously large image. The experience becomes more immersive, the figures more dynamic and alive.

Lighting at small scale is difficult, principally because photographic lighting is designed to light larger objects and spaces. Owens experimented with Lume Cubes, LED task lights, even an LCD projector and masks. None of them sufficed. The Lume Cubes were versatile and came with useful arrays of snoots and filters and grids which still required modifications to work at small scale. But the Lume Cubes had to be reset to the proper light level every time they turned off for overheating or battery exhaustion, which they did often. This was a major drawback; getting the right shot often entailed scores of exposures over many hours in the studio.

The problem was solved by his friend Steve Richard, who is an engineer as well as a noted photographer and photographic educator. Steve designed a remarkable kit of LED lights designed to work at small scale. They are controlled from a central power source that enables light selection and consistent level-setting. The light heads themselves are also wonderfully compact and light, which allows them to be on smaller stands, necessary to be able to cluster them, sometimes as many as six, in the small space in front of the miniature scene. Each light is mounted on a small “magic arm” to facilitate the very precise alignment this type of photography requires—often locating a 2-centimeter beam within a few millimetres. This is a unique, custom set of lights; none other exists, or will.

Movie makers often use larger models to facilitate lighting but Owens only works at small scale—1/12 or smaller.

Besides the difficulty lighting a scene convincingly are the difficulties with materials. Paint brush strokes stand out. Grains of sand—and jelly beans, M&M’s, pebbles, etc.– look disproportionately large. Surfaces are too reflective. Items can be hard to read. As Owens notes, “Of course, such restrictions and drawbacks all add to the challenge—and ultimately contribute to finding a voice, a working artistic vocabulary.” But if they are not overcome these intrusions on the small scale take the viewer out of the experience of the image and into disbelief. Which leads one to ask, what is belief, and how does it arise in these little, make-believe worlds? How do these little scenes somehow convey something recognizable and real to the viewer? “This is one of the aspects of the work I find most wonderful” Owens notes. “Small images, even the body language of little figures, seem to trigger paradigmatic responses in the brain so they evoke meaning and emotion.”

Backgrounds also need to be in place. For inside images walls are made, sometimes covered with dollhouse scale wallpaper printed from open-source files discovered on the internet. Outside backgrounds often involve printing large transparencies of images then hanging them behind the set and backlighting them.

Owens works in a studio purpose-built in his house. Besides housing his tabletop setup and photo gear it has special storage for the thousands of miniature figures and parts and materials he has collected, as well as fabrication space.

The work, it seems, is never as simple as taking a picture of a setup. All the problems of photography—focus, exposure, lighting, extraneous elements, composition—present themselves with miniature sets. Innumerable hours can be spent working on the body language of a figure or the position of a prop.

Owens has had a deep interest in photography going back to his childhood, and he has experimented in many types of work including landscape, architecture, street, and figure. Having retired from a career as a lawyer (his interest in the arts led him into the field of intellectual property), he concentrates now on photography. More of his images can be found at www.rcophoto.com.

Read this story and all the best stories on The Luminous Landscape

The author has made this story available to Luminous Landscape members only. Upgrade to get instant access to this story and other benefits available only to members.

Why choose us?

Luminous-Landscape is a membership site. Our website contains over 5300 articles on almost every topic, camera, lens and printer you can imagine. Our membership model is simple, just $2 a month ($24.00 USD a year). This $24 gains you access to a wealth of information including all our past and future video tutorials on such topics as Lightroom, Capture One, Printing, file management and dozens of interviews and travel videos.

- New Articles every few days

- All original content found nowhere else on the web

- No Pop Up Google Sense ads – Our advertisers are photo related

- Download/stream video to any device

- NEW videos monthly

- Top well-known photographer contributors

- Posts from industry leaders

- Speciality Photography Workshops

- Mobile device scalable

- Exclusive video interviews

- Special vendor offers for members

- Hands On Product reviews

- FREE – User Forum. One of the most read user forums on the internet

- Access to our community Buy and Sell pages; for members only.