We are coming to a significant crossroad in the evolution of digital photography. There is a convergence of factors underway that is changing the way in which we perceive the merits and value of the equipment that we purchase.

On the one hand we have a rapidly flattening slope on the image quality side of the ledger, where it takes a serious additional expenditure to derive what is often only a moderate increase in image quality.

On the other we have the worst global economic environment in our lifetimes, which is causing photographers to more seriously evaluate the value proposition of their purchases than ever before.

The third hand holds the issue of numeric analysis vs. the evidence of ones eyes. What do we do when the test numbers tell us one thing and ours eyes tell us another?

This is the first of a multi-part series of essays that will appear here during the month of February, which will attempt to address these issues. I invite you joinour discussion forumif you’d like to express your thoughts on this and future essays in this series. Let’s have a dialog about it.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Cloud Shrouded Mountain – Antarctica, January 2009

Phase One 645 with P65+ back and 75-150mm lens @ ISO 100

That Was Then

As photographers we are constantly searching for cameras and lenses that will produce the highest quality images. In the days before digital this search for the holy grail of image quality meant using the finest grained and highest resolving B&W films available, along with the best lenses that money could buy. Of course we also would shoot with the largest format that we could, along with using the best shooting techniques to optimize image quality.

But all of this came with a price – a practical one more often than financial. Yes, a 4X5" view camera could produce much higher image quality than a 35mm, but bulk and practicality were sacrificed for many applications. ASA 25 film had very fine grain, but didn’t lend itself well to hand-held shooting. Top-of-the-line lenses cost an arm and a leg, as they still do today, and primes not zooms were always the order of the day. Slow films along with large formats usually meant tripods, and optimum shooting techniques were a must if highest quality images were to be achieved.

____________________________________________________

This is Now

During the past ten years photography has undergone a massive shakeup. Many of the old rules have been turned on their heads, but others are as true today as they were before the turn of the past century, just nine years ago.

Whereas 35mm film was rarely able to produce high quality prints above 11X14", today with 21-25 Megapixel sensors 35mm DSLRs we can routinely produce 20X24" prints of excellent quality by almost any standard. This quality would once have been the domain of the best medium format systems.

Medium format backs are now available offering between 39 and 60 Megapixels, at a full 15-16 bit bit-depth. Such files, again – when shot with the best lenses and appropriate technique – can produce 30X40" prints that not just rival but easily surpass the quality possible from large format sheet film.

Boat Wreck – Half Moon Island, Antarctica. January, 2009

Nikon D3x with 24-70mm f/2.8 @ ISO 200

____________________________________________________

Price Not Size as a Determinant

More so that ever before though, price is a significant determining factor in what one can achieve when it comes to an image’s technical quality. In fact, unlike in the days of film when exceptional technical quality was possible from often modest systems – as long as the largest possible film sizes were used – the goodness of today’s sensor-based imaging system’s quality correlates most directly with cost rather than size.

So, putting aside common factors such as the use of quality lenses, appropriate shooting technique, and optimum post processing and printing, what we come down to is a paradigm shift. Yes, size does matter, but cost is a more significant determining factor when it comes to technical quality than in the pre-digital days where, all other things being equal, film size was the most significant factor. Then, a used $500 4X5" camera with a decent lens could produce a print which was technically head and shoulders better than that from the best and most expensive small format systems. Godzilla was right – size mattered.

____________________________________________________

The Value Factor

Today though, there is a direct link between image quality and price. Using the same lens a 1960’s $200 Nikkormat and a $1,500 Nikon F would produce identical image quality. The camera itself hardly contributed to image quality. It was the type of film and especially the film format’s size that mattered most.

This is definitely not the case when it comes to today’s DSLRs. Continuing the Nikon analogy, a D40 and a D3x produce different image quality but are separated by more than an order of magnitude in price!

Now we get to the crux of the matter. How big is that image quality difference? At a price ratio of 10X does this mean that the D3x is ten times better than a D40 in terms of image quality? Similarly, and so I’m not accused of Nikon bashing (I’m an equal opportunity basher) is a Canon 1Ds MKIII worth 10X the price of a Canon Rebel XS?

Since it’s obvious that today’s photographer contends with a different size / performance and price / performance paradigm than in the past, now more than ever we need to consider what I’m calling thevalue factor.

I shook up (actually pissed-off is more like it) a lot of people late last year when I compared the image quality possible from a $500 15 Megapixel Canon G10 with a $40,000 Phase One P45+ 39 Megapixel back on a Hasselblad H2.My little testshowed that on a selection of 13X19" prints a panel of industry pros couldn’t differentiate between the two more than roughly 50% of the time. What the hell was that about?

The answer isthe value factor, and the extent to which it is becoming a significant issue in the photographic industry.

Nikon fans were both excited and depressed when the D3x was announced. It appeared to be an exciting new flagship for the company, breaking Canon’s nearly eight-year-long dominance of high resolution pro-level camera bodies, but at over $8,000 the price seemeda bridge too far, as I called it at the time.

Why? Because of two things. The D3 camera, which is absolutely identical to the D3x other than for its sensor, costs $4,000. This means that the sensor alone in the D3x is costing us a cool $4 grand. But the Sony A900 also has a 25 Megapixel sensor and sells for under $3,000 – less than the cost of the Nikon sensor alone! What’s with that, especially since it is now known that these two camera’s sensors share the same underlying Sony fabricated silicon, so chip yield can’t be a significant factor?

Exacerbate this with Canon simultaneously shipping the 5D MKII, a sub-$3,000 21 Megapixel camera, and photographers were left wondering about a lot of things. Further compound this with the worst economic downturn in a lifetime, and the plot thickens.

Midnight – Marguerite Bay, Antarctica, January 2009

Sony A900 with Sony 70–300mm f/4.5-5.6 G @ ISO 200

____________________________________________________

Value vs. Perceived Quality

All of this was on my mind during the first three weeks of January during myAntarctic Photographic Expedition. Here were 77 photographers working together on a ship almost 24 hours a day for 13 days. These people were primarily advanced amateurs and pros, and more to the point, were affluent enough to have afforded a trip which, with travel expenses, cost close to $15,000.

Looking at the mix of camera system represented, about 70% were shooting Canon and some 30% were shooting Nikon – with lots of D700’s represented in that group. Of the Canon shooters a surprising 50%, a total of 26 people, had the new Canon 5D MKII, while among the Nikon shooters there was just one D3x (other than the test sample I was carrying).

Looking at the 50 Canon photographers we saw that the vast majority also had various expensive 1 Series bodies, and among the total group there were also eleven people shooting with medium format systems as well as their DSLRs. These consisted of ten Phase One backs mounted on a mix of Phase One and Hasselblad bodies, with one older Imacon (Hasselblad) back as well. Incidentally, this count did not include either me or Kevin Raber, who were also shooting with Phase One systems.

One last point of interest. Kevin and I were each shooting with the just-released 60 Megapixel P65+ back, and were loaning them to anyone on the trip that cared to try them. Of the ten people already shooting with medium format backs I know that six have now committed to upgrading to the P65+ after seeing what it was capable of – a very high percentage, and at not an inconsiderable expenditure.

The point I’m making is that this relatively affluent group of ardent amateurs and pros seemed through their purchases to be expressing a very clear bias toward a combination of both image quality and value. The value proposition of the Canon 5D MKII clearly appealed to many since 50% of them had bought one for this trip along with whatever other Canon cameras that they already owned, mostly 1 Series. Conversely, the perceived image quality proposition represented by the P65+ obviously appealed to existing Phase One owners on the trip, though the price of an upgrade is considerable – more in fact than the price ofanycurrent DSLR!

Thetake-awayfrom this, at least to my mind, is that those that can afford cameras that produce the best image quality will spend the money, but there has to be bothperceivedas well asactualvalue. Value in this instance is a multifaceted metric, representing a balance between dollars and performance.

____________________________________________________

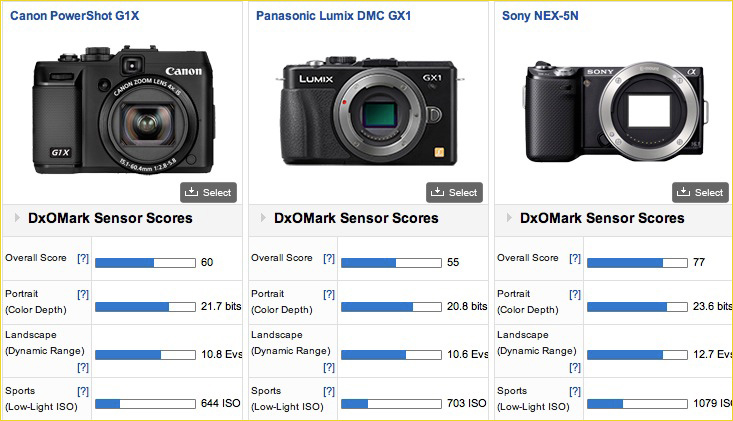

The Value Curve

One only has to look at the DxOMark chart which compares price to performance to see how various cameras compare. Above we see a chart that shows price on the bottom axis along with the DxOMark score on the left. The further to the right the higher the price, and the further up the chart, the better the image quality, according to their criteria. A DxOMark score without reference to price is a fairly meaningless number for most people, at least when it comes to making a purchasing decision.

Before going further I should mention that I also have a serious beef with DxOMark in that it does not take resolution into account. This seriously skews the results, because a relatively low resolution camera with high image quality (such as the Nikon D90) scores very well, though it only has 12MP. If you only make small prints, then that’s fine, but if largish prints or layouts are your thing then you have to take absolute resolution into account, and for this purpose 12MP is likely not enough, even if the image quality of those pixels is high.

As a consequence, a small group of individuals active in the industry, including an economist trained in the requisite mathematics, are trying to come up with a template which will integrate DxOMark ranking, price, and resolution into a composite that will be useful for people with varying needs in making purchasing decisions. More on this by mid-February.

So – keeping these caveats in mind, how do things shape up?

If you load this chart directly yourself on theDxOMark web site(I can’t link directly to it from here) what you’ll see is that the highest performing camera along with the highest price tag is the Nikon D3x, at the far top right. Based on my own shooting experience with it in Antarctica I can verify that indeed the image quality from this camera is outstanding, and it offers build quality and features that one can see are commensurate with it likely being the best DSLR currently on the market.

But, on the value scale it runs aground.

The highlighted camera on the graph is the Sony A900. Besides the D3x there are three other cameras which surpass the A900 in DxOMark score – The Nikon D700, D3 and the Canon 1Ds MKIII. In each of these cases the score differences are trivial, and in the case of the D3 and D700 these are 12MP cameras, not 25MP. As for the 1Ds MKIII it is twice the price of the A900.

Are you getting my drift yet? Unless you recently won the lottery, now more than at any time in most peoples lifetimes value has to be considered when making a purchase. How is value determined? By balancing price and performancebased on one’s own particular needs and abilities.

Using this metric, in my opinion the best camera value on the market today is the Sony A900. It offers the fifth highest DxOMark score of all cameras and of the four cameras ahead of it two offer only half the resolution and the other two cost between two and three times as much.

What about features and build quality? After a week in the Arizona desert followed by two weeks in Antarctica, all without a hint of problem, I can say that the Sony body and lenses offer all the ruggedness that most people need, and as for features, while not being the most feature laden, they do have such niceties as in-body stabilization and sensor dust shake removal, which the class-leading D3x doesn’t.

Am I trying to sell you an A900 or dis the D3x? No, of course not. This wasmychoice, not yours. It is completely immaterial to me what camerayoupurchase. As an equipment reviewer, teacher and journalist I own all three brands, and have paid for each of them them through purchase at retail. I have no brand loyalty or bias. Simply a personal preference for both high image qualityandvalue.

It was based on this calculation that several months ago I purchased a Sony A900 system, consisting of a couple of bodies and a selection of Sony and Zeiss lenses. Given the changing economic times I wanted to see how the marketplace was going to handle thevalue factor, and my calculation was that the A900 represented the sweet spot in that equation.

But – and this will really confuse some people, I have also just finished field testing a production Phase One P65+ back, a 60 Megapixel medium format back costing more than $40,000, and have decided to buy one by upgrading from my current P45+. Why? Not because I feel that the P65+ scores well on the value scale – by any measure it doesn’t – but because I believe that it scores at the absolute pinnacle of the performance scale, offering image quality beyond anything that I’ve seen before. So as a professional landscape and nature photographer I find this expenditure to be worthwhile –for me.

Car Shadow, Tin Roof and Flowers, Ushuia Argentina. January, 2009

Canon G10 @ ISO 200

____________________________________________________

Where Now?

Confused? Annoyed? Frustrated? Understandably.

Life isn’t simple, and neither are purchasing decisions. What I do, and the reasons why, may not be right for you, and visa versa. I have the freedom to buy different gear for long term use and testing because of the nature of my business. Few photographers other than the very wealthy do similarly (though I know a few, and some are also really exceptional photographers, so don’t be too cynicalabout those with high disposable incomeandtalent).

The point of this ramble is that we are now in a different technical as well as economic environment than most of use have lived though for the past several decades. On the one hand we have price being an absolute factor in determining image quality (the Nikon D3x and Phase One P65+ as but two examples), and a flattening price / performance curve as evidenced by the Sony A900, offering maybe 90% of the goodness of the higher priced spread at less than a third of the price.

And in an era where a $500 pocket camera like the Canon G10 can produce A3 sized prints that can fool industry experts as to whether they were from a medium format back, we really need to start applying some rationality to our discussions, if not our purchasing decisions.

Those who demand and can afford the very best will continue to purchase it, be it a Nikon D3x, a Phase One P65+, or something else. Those with high image quality demands but more moderate budgets will shop carefully and reap the benefits. And those with very low budgets will be able to purchase and use gear that while inexpensive is remarkable in its ability to produce excellent quality results when used within certain constraints. Not everyone needs either ISO 25,000 or 30X40" prints.

And, finally, I’m sure that there are still countless happy photographers out there shooting 4X5" film with their sub-$500 thirty year old view cameras and producing large prints of astonishing quality in the chemical darkroom.

Notwithstanding the dire economy, this really is the golden age of choice when it comes to photographic equipment.

February, 2009

Read this story and all the best stories on The Luminous Landscape

The author has made this story available to Luminous Landscape members only. Upgrade to get instant access to this story and other benefits available only to members.

Why choose us?

Luminous-Landscape is a membership site. Our website contains over 5300 articles on almost every topic, camera, lens and printer you can imagine. Our membership model is simple, just $2 a month ($24.00 USD a year). This $24 gains you access to a wealth of information including all our past and future video tutorials on such topics as Lightroom, Capture One, Printing, file management and dozens of interviews and travel videos.

- New Articles every few days

- All original content found nowhere else on the web

- No Pop Up Google Sense ads – Our advertisers are photo related

- Download/stream video to any device

- NEW videos monthly

- Top well-known photographer contributors

- Posts from industry leaders

- Speciality Photography Workshops

- Mobile device scalable

- Exclusive video interviews

- Special vendor offers for members

- Hands On Product reviews

- FREE – User Forum. One of the most read user forums on the internet

- Access to our community Buy and Sell pages; for members only.