We’ve had an interesting, partially post-COVID year in the photo industry, and I hope that next year will be a further unclogging of the pipeline and (more importantly) even more opportunities to get out there and make photographs. Every year, I take a bit of time to look back and forward at what we’ve seen in the previous year, and what we’re likely to see going forward. There are some things we aren’t going to see next year, despite a whole lot of Internet chatter – we aren’t going to lose a major camera company. Even the “some tech giant buys Sony” scenario is less likely than it has been, due to Congressional skepticism of giant tech mergers. There are things we might see – a 90-100 MP full-frame body, one last DSLR from somebody. There are things we will see – more Leica special editions that will never make a photograph, more stacked sensor cameras. We’ll get to the predictions in a later part of this article, after we give some awards for this year and look back at the last one.

I am more positive about the future of serious photography than I have been in quite a while – and I’m not worried about smartphones, nor do I think they have much influence on the photographic art form that Luminous Landscape readers tend to practice. There are two separate pursuits that share the term “photography”, and they share an early history dating to Niepce and Daguerre. One is the capturing of memories through snapshots – essentially impossible with early cameras, but always a goal – one of the reasons why 19th Century scientists worked so hard at writing with light. The second was the making of art with light and light-sensitive materials.

The two proceeded along closely parallel paths until around 1900. There is an oddly specific time and place for the divergence. The year 1900 in Rochester, NY is when the art and the snapshot diverged – and only partially because of Kodak being in Rochester – another player was there, too, with little connection. Photography was hard, and capturing a moment required quite a bit of dedication for most of the 19th Century. All cameras were essentially view cameras using a ground glass and film holder, until Kodak developed the first flexible film in the 1880s. By 1888, Kodak was selling a simple box camera loaded with 100 exposures of film for $25 (about $785 today). It was a very simple camera – fixed focus, no exposure control, not even any viewfinder. Within a year, a simple viewfinder and a couple of apertures had been added. By 1900, the original Kodak Brownie sold for $1, opening snapshooting to the masses.

In the same time and place, a camera repairman named Laban F. Deardorff was experimenting with wooden folding cameras, adding movements and messing with lens designs. He started out fixing cameras, but soon began to improve them, adding features and making them more precise. He would go on and move to Chicago, founding L.F. Deardorff & Sons there in 1923, after 30 years of repairing and modifying cameras. As much as a Kodak Brownie was the snapshooter’s choice, a Deardorff was the tool of many photographic artists including Ansel Adams, Sally Mann and Richard Avedon. Most wooden folding field cameras today are essentially L.F. Deardorff’s designs, and many more cameras than that are built for versatility and image quality as a Deardorff was. It may not be quite as simple as Kodak and Deardorff in Rochester in 1900, but that’s a decent summary of when photography began to split into its two component parts.

Certainly, many photographers who would go on to use a Deardorff (or a Hasselblad, or a Leica, or a Nikon, or a Canon, or some other precision instrument of choice) to create art started by messing with a Brownie, but the vast majority of Brownies sold didn’t lead to a serious interest in the art of photography. There are overlaps – Henri Cartier-Bresson created art using a camera from the scenes of everyday life, for example. No other art form I can think of shares its name and some basic technologies with a means of capturing daily life. People who don’t care about painting are unlikely to pick up brushes and canvas to record their breakfast. People who don’t love music are unlikely to write a song about walking their dog. People who don’t care about dance are unlikely to use movement to interpret an otherwise mundane event. If you do any of those things, there is some effort involved, some connection to the art form you chose. Writing shares some of the dual personality of photography – people write to record, and people write as art. A line recording someone’s height on a given day on a wall is a mundane written artifact of daily life, a capture of a moment in time not too different from a snapshot on Instagram.

When people say “the camera is dying, the smartphone has taken over”, what they really mean is “the smartphone is the latest descendent of the Brownie”. There is a whole history of tools for photography in the Brownie sense of the word, many of which have been picked up and used by artists in ways their designers didn’t intend. Cameras and lenses designed for the making of memories have tended to focus on being inexpensive, easy to use and at least somewhat rugged. 126 cartridges were among the earlier attempts to foolproof film loading, followed by 110, Disc and APS just before digital removed film from the world of snapshooting. Edwin Land’s Polaroid cameras offered snapshooters the chance to see their images right away. Both 35mm and 120 film have been used by snapshot cameras as well as by tools for the art of photography. Holgas, Lomos and Dianas were built as snapshot cameras, but were flawed enough that they actually worked better as tools for artists who loved and embraced their quirkiness.

The challenge for snapshooters has always been how to see and share their memories. While the taking of the image has been simple enough to do without caring about for 122 years, seeing and sharing it has always been harder. When you used up the film in the first Kodak box cameras, you sent the whole camera to Kodak to get it processed. By the time of the Brownie, you could replace the film and send only the film to Kodak. You could also process it at home, but people who did so were likely to be more interested in photography and to move from snapshooting to something else. For most of the history of photography, the snapshooter’s best option was to send the film off (or to drop it off at a store who’d send it off). In the last couple of decades before digital, one-hour photo labs became ubiquitous – operations where a machine would process and print your film for you without involving the post office. The only truly “snapshot-simple” way of seeing your images without involving someone else was Polaroid and its competitors.

In the early days of digital, the situation was much the same. Home photo printing using a computer was perhaps a little easier than using a darkroom (and much easier than using a color darkroom), but it wasn’t snapshot-simple. It was a rewarding tool for people who cared about photography, but it wasn’t a “I just want to see my memories” pursuit. The minilab industry tried “just hand us your card and we’ll make prints”, with only limited success. Snapfish and Shutterfly were a return to sending it off. Even getting images off the camera and into a computer, while a minor hurdle as soon as card readers worked without drivers, was harder than dropping the film off at the store.

There have been many attempts at super-simple home digital printing that would appeal to snapshooters, but nobody’s gotten it simple enough, and consumable costs are very high. One photography blogger actually tried a dry (inkjet) minilab printer at home – it worked very well and the ink and paper are cheap, but the upfront cost (a couple of thousand dollars) is prohibitive for almost everyone. Inkjets with refillable tanks are a possibility, and their consumable costs are very reasonable, but they are not really simple enough for snapshooters, who will always follow the path of least resistance (currently social media, texting, etc. – all of which work much better if your camera is a phone).

My office printer is an Epson ET-8550 (one of the most capable of this breed), and it’s a darned nice low-end to midrange photo printer. It’s much more than good enough for snapshots. I use it for prints to hand around, and I’ve just ordered a bunch of greeting card paper for it, thinking it will almost certainly produce greeting cards good enough to sell, at a price that makes it worthwhile. What it isn’t is simple enough for my mother (who hates computers, loves family pictures and couldn’t care less about photography) to use to print pictures of my nieces and nephews at Christmas. I could certainly do that while half asleep, as could my very creative sister-in-law. My brothers could do it easily enough, but it’s Mom who really wants the family pictures.

Image organization has always been a hurdle – shoeboxes, albums and multi-space frames are all ways that people try to organize and share. My parents have a lot of photos from my brothers’ and my childhood in something that looks like a Rolodex. Social media has made that easier, too.

What social media has done is that it provides the easiest way yet to see and share images. It is far more seamless if your camera has a continuous connection to the social media company – e.g. if your camera is actually a telephone. Posting to a social media site with an image from a camera that doesn’t connect directly is certainly possible, but it’s about a four step process. Make image with camera, transfer image to computer, find image on computer from social media site, post. If your camera is already connected to the social media company, it goes: Make image with telephone, push share button to post. That simplicity overrides all of the disadvantages of smartphone cameras for snapshooters.

The only way anyone will ever sell a non-phone camera for capturing memories again (in any quantity) is if it somehow has a share button on it that mimics the phone experience. Snapshooters would enjoy zoom lenses, which they had from the 80s until 2010 or so, and they might like better image quality than phone sensors – but they won’t give up any convenience to get them. If you put a cellular modem in the camera directly, it gets charged as an extra device on phone plans. It’ll be tough to get people to cough up an extra $20 per month for a zoom lens, better image quality and exposure controls if they don’t care about photography. The other possibility would be to have it tether seamlessly to a phone.

Camera companies have tried, but they have mainly proven that all of the camera companies are lousy at writing software. Apple and Google could certainly write the software easily enough (and they’re good at it), but the camera in the phone is one of the major features that drives upgrades – they don’t want users upgrading something other than their phone. Sony, who make both phones and cameras, has tried – but Sony isn’t especially good at writing software and the phone they came up with was an Android phone as expensive as a top-end iPhone. Android sells largely as a cheaper option and to techies who want the freedom it offers, not to people looking to simplify who are willing to pay for Apple’s best. If you’re paying iPhone money, Android’s ads and security holes are a big drawback to many buyers, and most of the remaining group are happy to go through a couple more steps.

That’s snapshooting – it’s not photography as an art. Social media, texting photos and the like are the best solution yet to photography as a way of capturing memories. Social media companies have managed to introduce profitable annoyances like incessant ads and invasive tracking because they solved the sharing problem so well. It’s the best Brownie yet, but what about the Deardorff?

Most of us who pursue photography seriously and artistically have always printed to share our work (perhaps along with some form of presentation that is now moving at least partially online). Many of us do our own printing, and others work with people we trust to print our work. We care more about control than utmost simplicity. We’ll get adventurous with paper, and we’ll work with raw conversion software. We can’t imagine working with only a 24mm f8 lens on a 2/3”, 12 MP sensor – unless we did it on a dare, to use nothing but a Holga and see what we came up with? Most of all, we can’t imagine turning every creative control we have over our images to AI.

We are the people who had darkrooms in the basement (or, if we’re younger, our first darkroom may have been digital). Inkjet printing is the new version of what we have long done under dim amber light with the smell of stop bath in the air. I’m optimistic that photography as an art will survive, that we’ll still be able to get the gear we need, and that there will be new processes joining those we have now. Sometimes, a new process replaces the old one – inkjet has essentially replaced most color darkroom processes, because it’s technically superior, more sustainable, and doesn’t really have any major drawbacks. Inkjet exists alongside black and white darkroom processes because it produces a different product. There will come a day when truly fine electronic display exists, and an electronically displayed photograph will be its own art form (right now, it’s still mainly a reproduction of a photograph). When that happens, it will be one more tool in our toolbox. There are still daguerrotypists left in the world, despite all the processes that have come since.

Our job as photographers is to pass on the art and the craft. We can help young people whose first introduction to photography was a phone, but who want to go farther, learn about composition, focus and exposure. We can help them work with lenses and how they see, and we can help them learn post-processing and printing. Our art is not dying because there’s a different kind of Brownie out there that is cheap to use and captures billions of memories each year. Photography and snapshooting are distinct – and what happens to one doesn’t really affect the other. If anything, an increased prevalence of snapshooting may help people discover photography.

2022 Awards

It’s time for a varying roster of awards. I don’t look at the same things for awards each year, because the important innovations aren’t always in the same places. This year’s awards include quite a few that any manufacturer should be happy to receive, but also some that photo industry players would rather not be named for – there are a couple of prizes in the fine tradition of the Ig Nobels and the Razzles here.

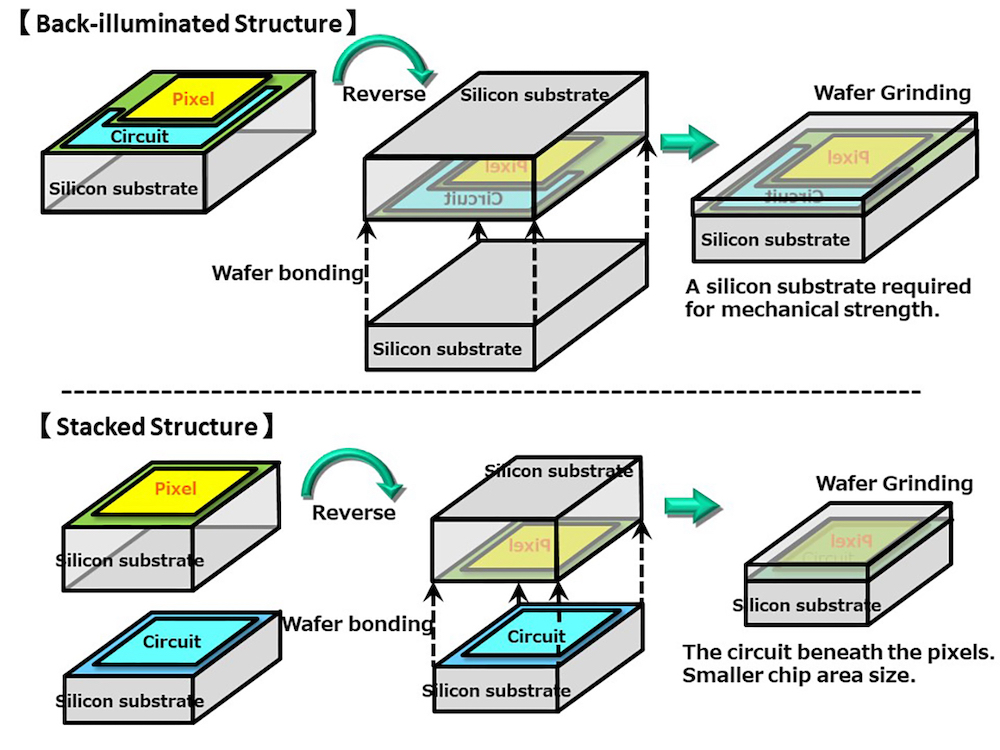

The big award of the year (Technological Innovation) goes to Sony, and specifically to Sony engineer Taku Umebayashi and his team, for the Year of the Stacked Sensor. It’s not often that we know exactly who made a breakthrough, but Sony has published Umebayashi-san’s name in a very interesting history of the stacked sensor. There have been a few cameras using stacked sensors for a while now. The first large stacked sensor was Sony’s A9 in 2017, and they’ve been in phones since Umebayashi-san and his colleagues invented the technology in 2012, but they really took off this year.

Ironically, much of the reason stacked sensors became so important this year was non-Sony cameras (mostly using Sony sensors) joining Sony in the marketplace. The Nikon Z9 and Canon EOS-R3 were both technically 2021 introductions, but they had their major impact in 2022 since they arrived on the market very late in 2021 in limited numbers, but became widely available in 2022. The Fujifilm X-H2S and OM System OM-1 were introduced in 2022 and cut the price of a stacked sensor camera more or less in half.

All but one of the current lineup of stacked sensor cameras almost certainly have something big in common – Sony sensors. The Canon EOS-R3 uses a Canon designed and manufactured sensor, but everything else is either in the “probably a Sony sensor” or “certainly a Sony sensor” category. Of course, Sony’s three stacked-sensor full-framers (A9, A9 II and A1) all use Sony sensors. The OM-1, Z9 and X-H2S are almost certainly Sony sensor cameras, although the Z9 sensor may have a heavy dose of Nikon customization in it.

Sony invented the stacked sensor, introducing the first smartphone-sized versions ,in 2012. All modern smartphones, with their AI processing, are dependent on stacked sensors. By 2017, Sony was capable of producing a full-frame stacked sensor, and they introduced it in the original A9. Until 2021, the A9 and A9II stood alone as the only full-frame cameras to use stacked sensors, and they were special-purpose speed cameras, sacrificing a substantial amount of resolution and some dynamic range for their incredible frame rates. In 2021 and 2022, we have seen stacked sensors become mainstream – there is still a dynamic range tradeoff, but it has become much smaller. The very highest resolutions at any given sensor size are not available in stacked sensors, but like dynamic range, the tradeoff keeps getting smaller.

What stacked sensors offer us as photographers is not just speed – although that is part of it. The speed of a stacked sensor gives us high frame rates and slow-motion video, but it also improves autofocus responsiveness and eliminates viewfinder blackouts. A stacked sensor camera is a joy to use for anything involving people or animals because it has the immediacy of a rangefinder – the photographer maintains contact with the subject through the whole process. If Henri Cartier-Bresson lived today, he’d choose a stacked sensor camera with the highest resolution viewfinder he could find. We lost the immediacy of a rangefinder through the whole SLR and DSLR era, because the mirror blocked the viewfinder at the moment of exposure by definition. Until the stacked sensor arrived, mirrorless cameras still had a viewfinder blackout, both because the shutter had to close in order to time the exposure and because the sensor couldn’t feed the viewfinder and the image processor simultaneously. Stacked sensors are so fast that the viewfinder need never black out during exposure (if the camera is using electronic shutter). It’s not quite the optical viewfinder of a Leica, but it’s darn close, and it works with any lens and with no parallax.

Perhaps the most important long-term benefit of stacked sensors is that they can eliminate mechanical shutters. A mechanical shutter is a complex piece of equipment – the shutter blades travel as fast as 30 miles per hour, and they have to accelerate to that speed in fractions of a millisecond. The forces involved in that acceleration are huge – hundreds of times the force of gravity, and many times greater than (for example) the forces imposed on an astronaut lifting off for the moon or a fighter pilot during a maneuver. Those forces make the shutter fragile and tricky to design, and they are capable of shaking the whole camera (shutter shock). If the sensor readout were fast enough, there would be no need for a mechanical shutter – the sensor itself could time the exposure.

Non-stacked sensors can offer electronic shutter, but their slow readout speed means that they have to scan the sensor line by line except at slow shutter speeds. The exposure time is right, since each individual line is only exposed for a brief time, but the scanning causes a couple of problems. Flash doesn’t work at any shutter speed requiring a scanned exposure, since the flash has to fire when the whole sensor is sensitive to light. Any flickering light will create banding in a scanned exposure, because some parts of the image will see the light flickered “on” and other parts will get it flickered “off”. Moving objects will appear distorted, since the top of the frame “sees” them in a different position than the bottom of the frame. Mechanical shutters scan, too, but they fully open without scanning at speeds up to 1/250 or even 1/320 second, and their scan speeds are fast enough to eliminate distortion except on very rapidly flickering or moving objects. Traditional electronic shutters may scan at speeds of 1/15 second or even slower, slow enough to cause substantial distortion and make flash a nightmare.

Stacked sensor scan speeds are approaching what a mechanical shutter can do. The best flash sync speeds using fully electronic shutter are around 1/200 second, not quite as fast as the fastest mechanical shutters, but respectable. That’s also fast enough to minimize rolling shutter distortion. Furthermore, improving those numbers is a matter of running silicon faster, rather than accelerating metal blades faster and more accurately. Science fiction author, rocket scientist (well, rocket engineer) and early technology blogger Jerry Pournelle stated “Silicon is cheaper than iron”, often referred to as one of Pournelle’s Laws. This is an application of Pournelle’s Law – it should be much easier to make a stacked sensor run faster than to accelerate a titanium blade more quickly and precisely. Within ten years, mechanical shutters will probably be a thing of the past (other than as sensor protectors for which speed and precision don’t matter). A non-stacked sensor in 2032 may well be as rare as a CCD is in 2022. It was 2022, the Year of the Stacked Sensor, when that really began to change. Congratulations, Sony and Taku Umebayashi.

The Camera of the Year is trickier than usual this year, because there are so few contenders. Last year, we had seven full-frame and medium format options to choose from (not counting several incremental updates), and the GFX 100S stood out for its incredible image quality in a crowded field with several highly viable contenders (the best of which are honored in the Year of the Stacked Sensor above). This year, we have only three full-frame options and one in medium format. All of the full frame options are somewhat incremental updates – the Canon EOS R6 II, Sony A7R V and Leica M11. The one medium format camera, the Hasselblad X2D, is a far larger update to its manufacturer’s line than any of the full-framers, but it breaks little new ground with 100 MP GFX already on the market. It adds leaf-shutter lenses that Fujifilm doesn’t have, but there are significant losses compared to Fujifilm, especially in autofocus and zoom lens availability. The X2D 100 is still worthy of an Honorable Mention, as is the A7R V, whose autofocus capabilities may prove very important, especially to wildlife and portrait photographers (sports shooters are likely to pick a faster, stacked-sensor Sony).

The award, however, goes to Fujifilm again, for APS-C this year. The X-T5 and the X-H2/X-H2S twins really extend what APS-C can do. Between the three of them, they offer the best image quality short of full-frame in a choice of two interfaces and one of the best still/video hybrids around. The X-T5 is a classic little street photographer’s or hiker’s camera, in the best tradition of the X-T line, with the best image quality we’ve ever seen out of a less than full-frame sensor. It also has superb image stabilization, in a camera that almost seems too small to be stabilized. Fujifilm has a great line of lenses to complement a camera that size – there simply isn’t that much camera available in that small a package anywhere else. Its interface is just plain fun to use!

The X-H2 and X-H2S twins are still very reasonably sized, and they offer a pairing that can do just about anything except the very largest prints. If you look at the X-H2, X-H2S and GFX 100S (which has a very similar interface, colors and workflow – although it, of course, uses different lenses) as a triad, they can literally do anything you might ask of a camera. The X-H2S is one of the best still/video hybrids on the market, offering video capabilities in the range of the Panasonic GH6 with much better still image quality. It also offers full-on speed camera capabilities for half the price of any of its full-frame competitors. Yes, a Sony A1 or a Nikon Z9 will offer even better image quality without losing any speed – but at an enormous price premium (and how many photographers need 20×30” prints and 20 fps simultaneously – if you do, the Z9 and A1 are there for you). The X-H2S is actually faster than either the A1 or the Z9 in full resolution raw capture (40 fps for the X-H2S, while the Z9 and A1 both have to turn on image quality robbing options above 20 fps). It’s one of the fastest cameras around, one of the best video cameras around, yet it’s still priced as a midrange camera and versatile enough for an all-rounder. College newspapers (and many others) take note.

The X-H2 offers even better still images, at the cost of the incredible speed, in an identical body. An X-H2/ X-H2S bag offers a tremendous range of capabilities at a very reasonable price for a professional kit. Almost every lens one might want is available, with older designs being replaced by lenses better suited to the high-resolution sensor. The ecosystem of flash and other accessories is rapidly improving. For the ultimate in photographic capability as of December, 2022, pair an X-H2S with a GFX 100S. Their operating philosophies are very similar, closer than, for example, a Nikon D850 and D5, a very common professional pairing for speed and resolution (although not as similar as a Sony A1 for speed paired with another A1 for resolution ☺). The GFX offers unique image quality, and the X-H2S adds speed and video. Their colors and overall look are very close, and they work very well together. The two sets of lenses are really the only disadvantage, and they are inevitable to get that range of capabilities – no smaller sensor can keep up with the image quality of the GFX, and there is no medium format sensor that can offer the speed of a smaller sensor camera. Even if a stacked sensor radically increases the speed of medium format, long telephotos would still be a drawback, suggesting a pairing with a smaller sensor camera.

Lens(es) of the year is shared between Fujifilm and Nikon, for opposite ends of the focal length range. Fujifilm’s share of the award is for the GF 20-35mm f4. One of the biggest drawbacks of medium format has always been wide angle. Landscape photographers have always had to drop back to 35mm (or use a 4×5” view camera with the 47mm Schneider Super-Angulon XL) to get a really wide perspective. Until the recent digital mirrorless systems from Fujifilm and Hasselblad, anything below a full-frame equivalent of 28mm or so has been (at best) rare and exotic. Both Fujifilm and Hasselblad have had a mirrorless prime wider than that for a few years, but only a single choice in focal length. Fujifilm not only went wider than either they or Hasselblad had done before, but they did it in a zoom lens. I love having zoom on my widest lens, because it is so useful for eliminating unwanted branches from the edge of the frame.

When I saw the specs of the GF 20-35mm f4, I thought “this is going to be a huge lens”. Medium format wide angles have never been small, and a constant aperture zoom that went wider than medium format had ever gone promised to be bigger than most. When I saw the lens for real, my response was “you have to be kidding me – that’s a full-frame lens, right?”. Nope, it’s a constant-aperture, medium format ultrawide zoom that only looks like a mere full-frame lens. Its full-frame equivalent focal length and aperture is something like 16-29mm f3.2, and if you handed me this lens and told me it was a 16-29mm f3.2 for Sony FE, the only physical indication it’s not would be “that lens mount’s awfully big”.

It uses some electronic correction to deal with vignetting and chromatic aberration, as all modern ultrawide zooms do – but it’s sharp right into the corners, and distortion is minimal given the focal lengths. The combination of lens and sensor offers the best image quality I’ve ever seen at angles of view that wide, and not by a small margin, either. The only possible competitor would be the aforementioned 47mm Super-Angulon XL on a view camera (I’ve never seen one). Full review forthcoming when I get a chance to do some serious printing from the lens – but my preliminary opinion is “wow”.

At the opposite end of the range, we’re looking at a remarkable turnaround for Nikon. If you walked into a camera store in December of 2021 and asked for a long lens for your Z-mount camera, you’d have three options. The 70-200mm f2.8 would have probably been on the shelf, and it’s a great lens, but it takes a teleconverter to get past 200mm. There were a number of F-mount lenses that worked very well on the FTZ adapter, and there was no reason to replace many of them (especially the 300mm f4 and 500mm f5.6 PF lenses, which balance especially well on the smaller Z-mount bodies) if you owned them. Buying an adapted lens new, though, gives many people the jitters, and anything top-end except the PFs is a little heavy for the adapter. Nikon specs the FTZ for 46 ounces, although you can go heavier than that with care – mostly the care you’d use with a long lens anyway – put the strap on the LENS, mount the lens instead of the camera to the tripod.

What you don’t want to do is bend your lens mount by having a big, heavy lens hanging out there unsupported. The 500mm PF is just a tiny bit over the limit for careless FTZ technique, and is almost certainly OK long term if you’re careful and use proper long lens technique. Anything bigger (any exotic prime, the 180-400mm or 200-400mm f4 zoom family, the 120-300mm f2.8, or even the relatively inexpensive 200-500mm f5.6 or a big Sigma zoom) is well over the limit, and should be used with a lot of care if at all. I’m almost sure Nikon used to set the FTZ recommendation at 4 lbs, which would have put the 500mm PF well inside and brought the others closer.

The last option was a semi-mythical (as of last year) 100-400mm f4.5-5.6 S-line native Z-mount lens. There were a few very promising reviews out there, from folks who’d had early access, but there was no way to buy the lens – it was on backorder everywhere. Very, very few backorders had been filled – a few pros with NPS access had them, but even most NPS folks were still waiting. That was all as far as lenses over 200mm went. It was the biggest hole in the Z system.

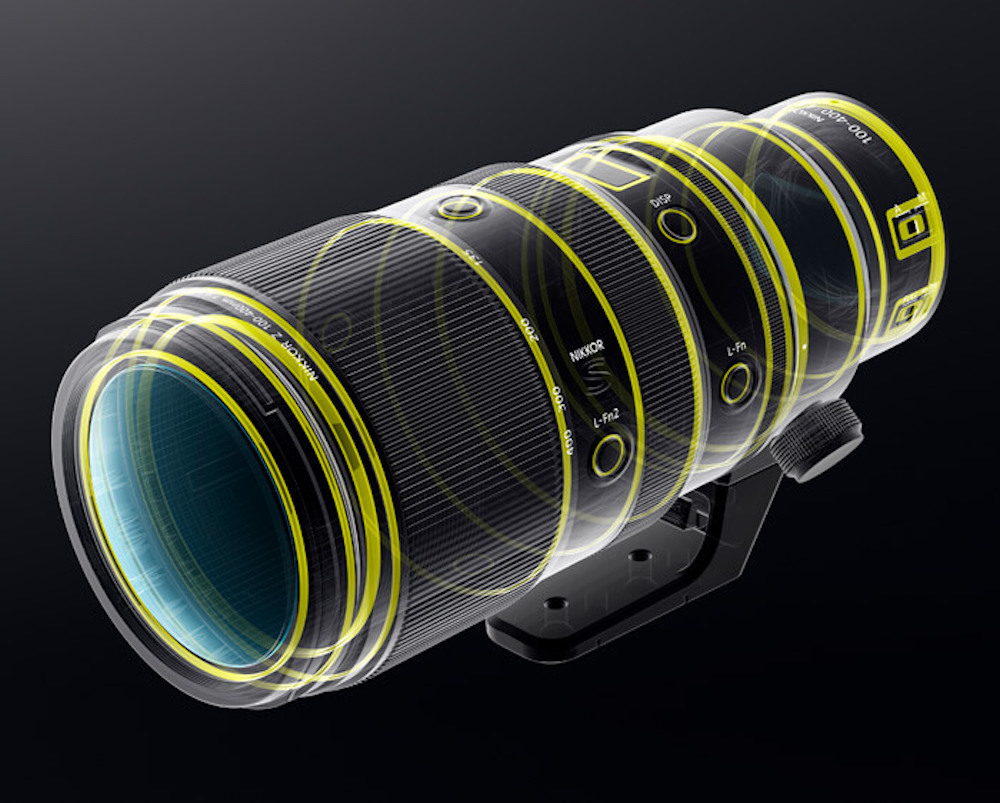

What a difference a year makes! Nikon is the telephoto market leader! The 100-400mm is widely available everywhere, and it is generally reviewed as the best 100-400mm zoom in existence. There’s a remarkably compact 400mm f4.5 (it’s not a PF, but it looks like one) that is getting excellent reviews, and is often available (in stock most places as of this writing). It is a true exotic-grade performer a step up from any 100-400mm zoom in a sub-3 lb lens, and according to Nikon guru Thom Hogan, it tolerates the 1.4x teleconverter very well. There’s an 800mm f6.3 PF that is by far the most practical high quality 800mm ever made – it’s backordered, but they are showing up in people’s hands. It’s big, heavy and expensive, but MUCH less so than you’d expect to look at its spec sheet.

At the very top, there are 400mm f2.8 and 600mm f4 exotics, both with built-in 1.4x teleconverters, both at the absolute pinnacle of image quality. Any time Nikon, Sony or Canon releases a new lens in this range, they leapfrog the other two – and Sony’s exotics are older, while Canon’s are older EF mount lenses with the mount converters permanently attached. Until one of the other two updates theirs, or unless Sigma puts out an audacious telephoto over $5000, advantage Nikon. Sigma could release a $6000-$9000 400mm f2.8 or 600mm f4 with a built-in converter that competes with the $10,000+ Nikkors – that’s just Sigma being Sigma. One important thing to note about that built-in converter: you get TWO exotic lenses for your huge investment and the bad back it’ll give you to carry. If you choose the 400mm f2.8, you get the two most popular focal lengths and apertures, because it’s also a 560mm f4 (no, it’s not quite a 600mm, but it’s close). Both are, of course, backordered – all exotics are for their first year or two on the market, because those big fluorite elements are very slow to produce. If you ever see a lens like these go in stock everywhere in its first year or two on the market, that means the manufacturer screwed up and the sports photographers rejected it!

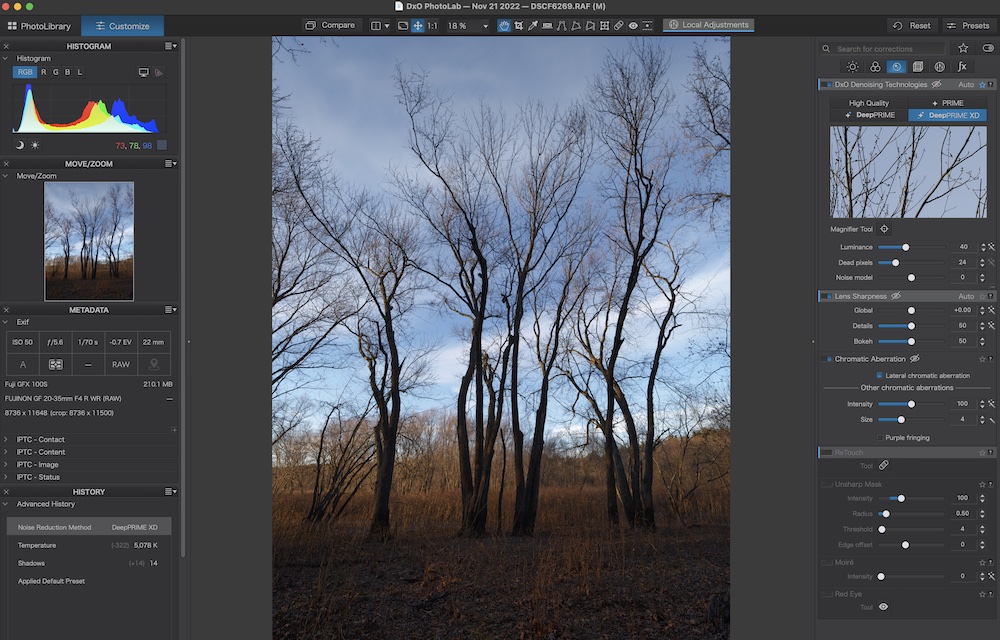

One more positive award – for software. DxO PhotoLab 6 maintains the image quality crown, and their interface and features keep getting better. I have access to all of the major raw converters – I pay for Adobe (and have for years before I started reviewing), and get consistent review copies of both DxO and Capture One. More detail in a forthcoming article, but DxO’s DeepPrime XD noise reduction/ demosaicing is every bit as good as they claim. It’s slow, bordering on very slow on very large images – but it is excellent. All such algorithms make the most difference on compromised images (older APS-C at ISO 3200, for example), but DeepPrime XD makes a difference even on GFX 100S images at ISO 50. Yes, it’s a pixel-peeping difference – but if you’re using that camera at low ISO, you’re shooting for the very best, and DxO delivers. Their brand-new correction profile for the GF 20-35mm f4 is also excellent (as I would expect – I’ve never met a lens profile of theirs I didn’t like). Their local correction is the best burning and dodging function is the best in the business, and it keeps getting better. Their new DxO Wide Gamut color space makes a difference on files from cameras that go beyond Adobe RGB.

All isn’t perfect – it’s the least integrated of the three big raw conversion packages. DxO works with your existing folder structure, and it doesn’t even offer an option to organize your images. People don’t like Lightroom Classic because it forces its catalog on you, but it’s a very capable catalog. I’d love to have the option of either Adobe’s approach or DxO’s – maybe I need to investigate Photo Mechanic or the like along with DxO. DxO also doesn’t work with Loupedeck or any other control surface – I’d love to see them add this as well.

Lightroom offers fantastic integration of just about everything, but their core raw conversion lags consistently behind what I’m able to achieve with Capture One and especially DxO. I use the GFX 100S for landscape, the Sony A7R IV for wildlife, and I have a lot of Nikon images as well as those from various review cameras. The order of DxO PhotoLab>Capture One > Lightroom Classic is consistent across those cameras. One thing I don’t have is Canon images (they are the one brand that I can’t get review cameras from) – and some say they are Lightroom’s greatest strength.

The biggest thing I’d like to see DxO add is a print module. There is almost no printing capability in DxO PhotoLab – the best you can do is either print straight from the raw converter to the OS print dialog (this leaves resizing to the print driver, which will do it badly) or export the image from DxO (with better resizing) as a print-size TIFF and open the resized image in DxO itself or Preview (it doesn’t matter which – DxO simply calls the OS print driver, and Preview can do that as well). There may be an advantage to opening the image back up in DxO if you’re using Windows, because I don’t know if Windows’ Preview equivalent will let you assign a printer/paper profile – Preview will. Of course, the right way to do this is to export the image from DxO as a TIF and then open it in something more capable for printing – ImagePrint, QImage, or your printer manufacturer’s included software (Epson Print Layout or Canon Easy PhotoPrint).

DxO to ImagePrint is simply the best pipeline there is, and ImagePrint’s resizing and output sharpening are really excellent – but ImagePrint is far from cheap. Because ImagePrint’s tools take over where DxO’s leave off, you only need to export the TIFF once – original size, 16-bit, Adobe or ProPhoto RGB, all sharpening except output sharpening completed. ImagePrint will handle resizing, output sharpening, profiling and layout. If you’re looking for the best in fine art printing, the combination of DxO PhotoLab and ImagePrint simply can’t be beat. I rarely bother going from DxO to Photoshop to ImagePrint – I can do most of my editing right in DxO PhotoLab, because of the excellent local editing tools. The two cases where I DO involve Photoshop are with panoramas, or when I need some plugin outside of the Nik Collection (owned by DxO, and works in DxO PhotoLab). I don’t expect that a hypothetical DxO Print module would compete with exporting to ImagePrint or QImage at first, but it would offer a streamlined workflow for quicker or less critical prints, or for people who enjoy printing, but don’t want to buy or learn a separate print package.

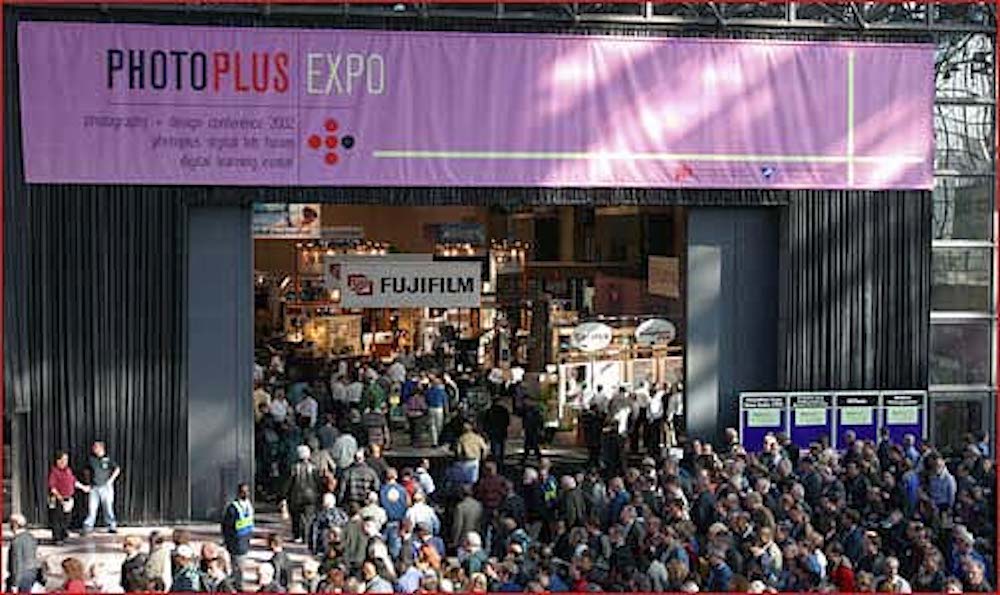

Now for some awards a company would rather NOT get. The big Worst of Show award goes, and this will be no surprise to people who’ve read my recent articles, to Emerald Expositions, for the loss of PhotoPlus as we knew it. Whether or not they get their TikTok-focused show off the ground, it is increasingly clear to me that they have no interest in a photography-focused show like the old PhotoPlus was. Where will we see prints from every camera and lens we could imagine? Where will we see beautiful images on every paper in five or six manufacturers’ lines? How do we choose papers from a 3×5” swatch book – I want to see a 30×40” print before committing to a roll, and PhotoPlus was full of them. Where will we be able to talk to the manufacturers’ knowledgeable representatives in person, and handle all possible cameras and lenses? Where can we find gear from ArcaSwiss and the tiny Kickstarter companies? Where will we see and hear presentations from photographers like Steve McCurry and Lynsey Addario?

The demise of PhotoPlus leaves a big hole – and someone could fill it. A big national dealer like B&H or Adorama, or even a major regional dealer like Hunt’s or Samy’s, could get a lot of the manufacturers to show up. Hunt’s used to rent an expo center in Boston and do kind of a mini-PhotoPlus. They now do a smaller version at their flagship store. Could the Hunt’s Show and other regional shows grow to fill some of the space that the loss of PhotoPlus leaves open?

The Runner-up for Worst Of Show goes to Kickstarter, Indiegogo and Amazon Marketplace for flooding the market with low-quality photo gear, some of which is actually dangerous. Kickstarter and friends are huge risks – they are specifically designed to serve as liability shields. You may never see your gear, it may not be as you expected, and in the worst case, it may be dangerous. When we used to be able to see some of that gear at PhotoPlus, it was a huge help.

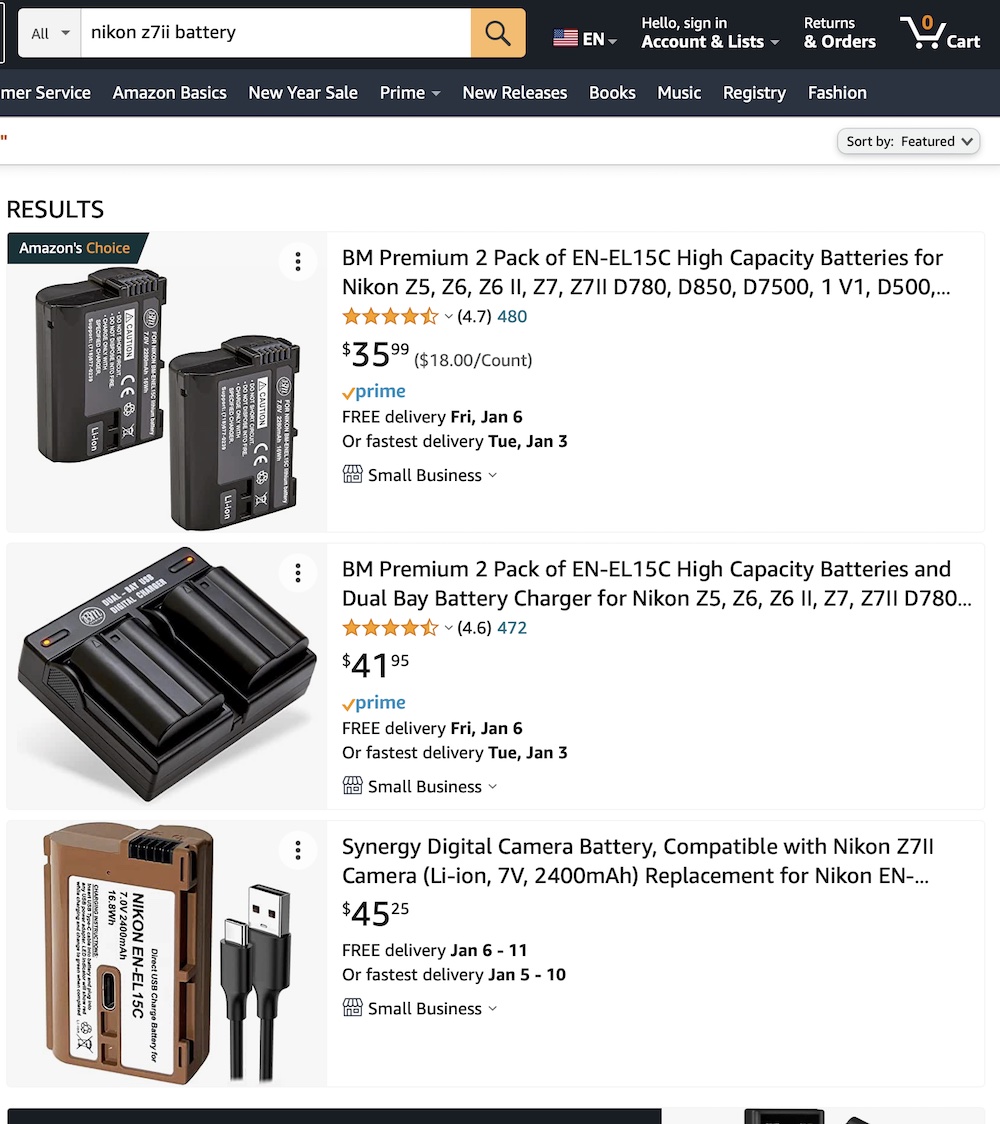

No Nikon battery, no well-known brands. Lithium-ion batteries can go BOOM if they are improperly designed. The situation is getting slightly better – searches for a few other popular batteries DID include the original, sometimes with an Amazon’s Choice banner. A couple of years ago, pretty much any battery search would have included only unknown brands!

The worst case of all is batteries and chargers. There are a lot of appealing looking products on Kickstarter and Amazon Marketplace, but there is absolutely no liability if something goes wrong – both Kickstarter and Amazon Marketplace are very cleverly designed by lawyers to make absolutely sure there is nobody to sue. This is enabled by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a shield the big Internet platforms use to hide from a lot of things – the same law is also why hate speech, libel and Russian propaganda are all over social media.

Lithium-ion batteries are a special problem because they are DANGEROUS if mishandled. If you get a bad filter, it might ruin your picture – but take it off your lens and the damage is undone. If you get a bad lens, you might waste a bit more money, but it still won’t hurt anything else. If you get a bad strap or tripod head, it might dump your valuable camera and lens, and if you get bad ink, it could clog your printer. A bad battery or charger could EXPLODE, burning your house down or even injuring you. This is EXTREMELY unlikely with reputable gear, but it is MUCH more likely with zero-liability stuff from Kickstarter or Amazon Marketplace.

While we have the zero-liability problem, I stick to the original manufacturer’s batteries and chargers, and to a few trusted third parties. For things that aren’t potentially dangerous, I look at the risk to the image, and to my equipment. When it comes to the dangerous stuff, I stick to the original manufacturer when I can. I use chargers from Nitecore if I can’t find what I want from the original manufacturers – why most manufacturer chargers aren’t USB compatible is beyond me, but most of them aren’t (and no, using a $1000-$6000 camera as a $30 battery charger isn’t a replacement). Kudos to Fujifilm for a very nice USB-C charger for their recent batteries (although with a caveat – it should come with the camera!). Nitecore makes excellent USB chargers for most things (some of the newer ones are even USB-C), and they’re a battery company who know how to make a safe charger. They make some camera batteries, too – and I’d trust them. Another good source for camera batteries if the manufacturer battery is unavailable is Watson (a B&H brand). When I looked at batteries a few years ago, Watson batteries were consistently right behind the manufacturer batteries in capacity, and they incorporate all the same safety features.

Canon doesn’t make a 20mm RF lens of any sort, and they won’t let Sigma sell this one, which they make for Sony FE and L-mount.

A Dishonorable Mention goes to Canon, for knocking third-party lenses off the RF Mount, and for using EF-M lens designs for their new APS-C RF bodies. Canon’s RF lens lineup is growing, but it’s still missing a lot, particularly in the middle. Canon knows how to make a beautiful lens, and they are doing so at the top of the line. Their L series lenses on RF bodies generally hold up the L Series reputation. They’re also releasing a lot of inexpensive lenses. Some of them are common beginner lenses and beloved older designs (a slow 24-105mm kit lens, a sub $200 Planarish 50mm). Others have a twist – a cheap, slow 100-300mm becomes a cheap, slow 100-400mm, a 15-30mm zoom under $600 (midrange, but downright cheap for a wide full-frame zoom). A few are really unusual, like the sub $1000, collapsible, Fresnel 600mm and 800mm lenses.

What they don’t have is good midrange lenses – very few f1.8 (or so) primes with modern designs, only one telephoto in between the cheap (sub-$1000) lenses and the $10,000+ exotics. They do have a nice set of f4 zooms, but no primes to go with them, and no higher-end APS-C lenses to match the new RF-S bodies. Letting third-party lenses onto RF would solve the first problem (the Sigma Art lenses and some of the Contemporaries are pretty much exactly the missing primes), and help with the second. Sigma and Tamron have some nice APS-C lenses , including Sigma’s 18-50mm f2.8. Right now, the only two native lenses for the R7 and R10 are ultra-cheap zooms that came over from EF-M (and the greatest weakness of EF-M was that most of the lenses were junk)! Canon needs to make their own decent APS-C lenses and midrange full-frame lenses, AND they need to let Sigma and Tamron onto the RF mount.

A second Dishonorable Mention goes to Pentax/ Ricoh and OM System, for relabeling cameras. Both the OM System OM-5 and the Pentax KF are VERY minor refreshes of older cameras, sold as actual new products. As much as anything, they may be redesigned to use parts that are still available when something became hard to get due to supply chain woes. Sony got this one right – they did the same thing to the A7R III (A7R IIIa) and A7R IV (A7R IVa) and admitted straight out that they were parts availability refreshes. The Sonys have a few minor customer-friendly refreshes, like substantially sharper rear LCDs – more of a refresh than the Pentax KF got (it got a new LCD, but not as big a change). Both Pentax and OM are trying to pass off similar refreshes as new products.

Dan Wells

January 2022