My Journey Begins

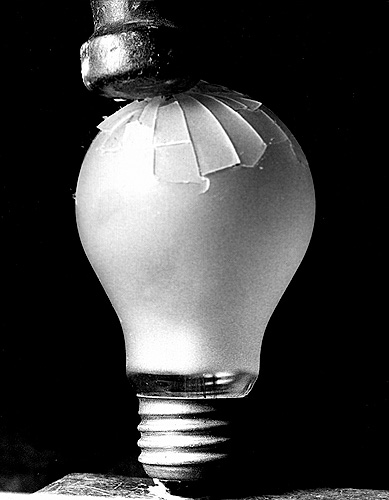

My first memorable encounter with photographic lighting happened when I was a teenager. Fascinated by light and the element of time as it relates to photography, I successfully recreated a Harold (doc) Edgerton style image of a hammer crushing a light bulb, using a hot shoe flash trigged to a pressure switch in a darkened room.

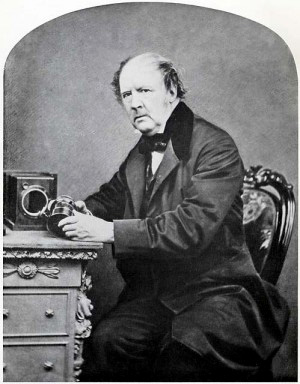

Like many before me, the curious interplay of light and time has been of particular interest. In 1850, William Henry Fox Talbot gave life to this concept by capturing an image of newsprint fixed onto a rotating disc in a darkened room using an electric spark powered by energy stored in an array of Leyden jars an early form of storage capacitor technology. This experiment was the first documented use of electronic flash for photography. Little did I know that my early interest in flash would eventually lead to a chance encounter with the work of Mr. Talbot.

A Legacy of Light

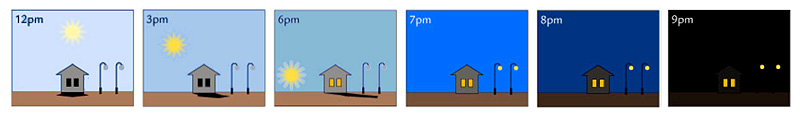

From its inception, photography has ultimately been about capturing light. The most important light source that remains since the early days of photography is the sun. Natural sunlight is constantly in flux; from the warmth of the morning, to the spectacular colors of the night, natural light still provides us with unlimited nuances of intensity and color.

Daylight is constantly in flux

A true photographer is a master of light. Regardless of the capture medium, or digital post-production prowess, the core essence of a photographer’s art is the ability to control and manipulate light. The more power and mastery we have over light, the more power and control we have over our creativity. Light puts Photoshop ® to shame as the most creative and effective imaging tool yet, unfortunately, many photographers have shifted their focus from mastering light to mastering post-production software. As a result, they often find themselves in a costly and time-consuming cycle of perpetual training and software upgrades.

In an effort to gain more control over light, generations of photographers have attempted to emulate natural light. My generation grew up with electronic flash; the generation before used hot lights, and the previous generation used daylight (and flash powder). I predict the next generation of photographers will be using LED flash lighting, and will expand on this prediction after first taking a look at the pros and cons of current lighting technologies.

Artificial Light

The most common lighting tools used today are tungsten light, fluorescent light, HMI light and electronic flash. Each technology has distinct advantages and disadvantages. While I will discuss each in detail, all have one key drawback in common, they are essentially fixed in terms of color temperature. Because the color temperature is fixed, these light sources are not able to emulate the ever-changing nuances of natural light. Digital cameras typically have presets for daylight, flash, tungsten and fluorescent light sources in an effort to arrive at pleasing results under these traditional illuminants. We all know that these presets do not deliver predictable results, because it is rare that real world lighting conditions are truly homogenous. Digital cameras cannot rectify the difference between daylight and tungsten in the same scene, so at best, a compromise is made. Of course, when working with digital raw captures, white balance is simply a meta-tag signaling an image processing parameter that can easily be altered in image processing software. Camera sensors do not know the difference between daylight or tungsten sources, they simply gather and store light energy.

Tungsten Light

Tungsten light is well known and is the most primordial technology. I say primordial because the spectral emission of tungsten light is almost exactly that of a candle or campfire. Everyone you know has been exposed to tungsten light throughout their entire lives. Our connection to tungsten light is so strong that billions of dollars have been spent over the years to simulate its effects in newer lighting technologies. However, in terms of digital imaging and camera sensors, the lack of blue light energy does not help the blue channel of your CCD or CMOS sensor. The same is true of extreme infrared radiation, which is why most camera sensors have a special iR cut filter to literally block this energy. While newer sensors have better noise reduction to compensate for these issues, tungsten light is simply not the ideal light source for digital imaging. Tungsten light has a relatively fixed color temperature of around 2800-3200K. As a point source light that radiates energy evenly from a single origin, tungsten light is wonderful in terms of creative control. When you watch an old black and white movie, or look at classic movie star photos from the 1930s to 1950s, the light quality is simply amazing due to the wide range of tungsten reflector and lens options and, of course, the lighting skills of that generation of artists.

Fluorescent Light

Fluorescent light is a technology that few photographers truly enjoy. Though more energy efficient than tungsten light, there are many more drawbacks to this technology. The greatest drawback for imaging with fluorescent is the fact that the light does not emanate from a single point; there is simply not enough intensity to produce a significant amount of light in a small area. Spectrally fluorescent lights are a mixed bag, they can be engineered to offer a near daylight color balance, but there are numerous spikes and gaps in the spectrum. Color temperature varies from lamp to lamp type, but generally these light sources operate at fixed temperatures between 3200 and 7000K. After years of research and development color rendering has improved, but a digital camera does not see as we see. It’s simply a monochromatic sensor with a matrix of RGB filters. Often, depending on the filter array of a particular camera sensor, color quality can be compromised. The net effect is that in subtle tones like skin you may see banding effects from missing colors. Older fluorescent lights suffered from flickering which rendered them useless for film and video frame rates, but today most fluorescent lights are high-frequency and can be used for film and video applications. The primary drawback of fluorescent light sources is the inability to shape the light. The ingenious Plume ® Scandles ™ designed by Gary Regester are the only fluorescent lights that could be considered to have some useable directionality. Scandles ™ became popular for digital scan camera illumination and video applications; but due to extremely fragile glass tube lamps, they are limited when it comes to location work.

HMI Light

Like fluorescent light, HMI is a technology that is utilized more by necessity than choice. It emits a very full, even spectrum that is ideal for digital sensors and is almost always between 5000 and 5500K, but HMI lights emit a significant amount of UV and iR radiation. HMI lights and bulbs are fragile, extremely expensive, and have a short operating life. Due to heat, the options for light modification accessories are limited. What HMI does offer over other light sources is tremendous continuous power output and point source control. This is why you see HMI lights in use across the film industry. In many ways HMI is the electronic flash of the film industry. It is often used outdoors to provide a consistent supplement to daylight, or as a fill. When I see location trucks full of HMI lighting for film productions, I can only think of how cumbersome and awkward this technology is.

Electronic Flash

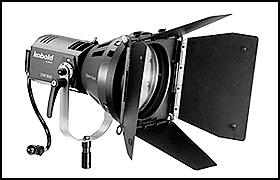

Electronic flashis the light of my generation. For still photography electronic flash is the de-facto standard because it offers a consistent 5000 to 5500K full spectrum light that is very close to natural daylight. On the downside, electronic flash light emits energy beyond the visual spectrum with large amounts of UV and iR radiation even with so-called UV coated flashtubes. The great advantage of electronic flash is the ability to store and release great amounts of energy in a small window of time. This short duration is what helps photographers freeze action. Most studio flash units operate around 1/250th of a second. Small on-camera flashes are actually faster, well over 1/1000th of a second. Some high-end studio strobes offer variable duration and some limited control of color, but in general these lights are fixed and consistent. To this day, there are a large number of photographers that still prefer tungsten lights. This is primarily due to the fact that the model lamps and flash tubes of electronic flash systems are different color temperatures and throw different light patterns. Aside from these issues electronic flash offers the photographer wonderful light shaping capabilities with spots, dishes, zoom reflectors, grids, barndoors, fresnels and softboxes. The one thing that electronic flash does not offer today’s photographer is video capability. Also, as digital cameras have increasingly higher ISO ratings, the brute power of electronic flash has become less of a priority.

My Second Encounter with Electronic Flash

My first job after graduating from RIT in 1984 was working as a technical representative for Balcar Flash in New York’s Photo District. Later I worked for Ken Hansen Photographic in Ken’s lighting department and eventually at Ken Hansen Imaging. Electronic flash is near and dear to me. During this period I recall two notable projects: as a lighting consultant to Neil Slavin I helped design the lighting to illuminate the New York Stock Exchange for the publication “A Day in the Life of America” (1986). Inspired by this project, I set out to photograph the entire audience attending the grand re-opening of Carnegie Hall in 1987. To make things interesting, I chose to use an antique 8X10 camera and over 20,000 watt-seconds of electronic flash. (Only a 25 year old would be crazy enough to use a vintage 8X10 sheet film field camera for such an occasion!)

©1987 Scott Geffert

The photograph was technically successful in that every face in the music hall is tack sharp, but frankly, it was aesthetically unsuccessful. The daylight “color correct” flash units completely overpowered the ambient tungsten lights ruining the sense of warmth that suffuses this beautiful concert hall. From that experience forward, I have always been preoccupied with color and the limitations of electronic flash.

The Current Lighting Dilema

The merging of still photography with video technology presents new lighting challenges

The lighting technologies highlighted above are fully established and have been in wide use since well before the digital imaging revolution. In terms of core technology, all have reached a plateau in which that there is really no room left for innovation. In my opinion, little has changed in lighting since the late eighties, though the rest of the photography world has moved on.

None of these lighting solutions have been purpose-built for digital imaging use. As today’s cameras have become more advanced, traditional limitations in lighting have become an issue. Many of today’s DSLR cameras offer HD video capabilities. Photographers are getting more involved with cross-media imaging where the client needs stills as well as high quality video from the same creative session.

Filmmakers are also moving towards HD production and digital cinema tools like the Red camera. In these new scenarios the photographer is forced to make compromises. If they use strobe lighting for the stills, they need to switch lighting for the video work. If they use HMI lights or tungsten lights they may not be able to get the same precise control. Managing the white balance between sources and cameras becomes difficult and results in more costly post-production. In short, photographers are often purchasing two sets of costly, incompatible lighting equipment. In today’s leaner cross-media imaging culture, photographers simply cannot afford to own or even rent redundant equipment. More importantly, being forced to compromise on lighting limits creative control.

The Past as a Guide to the Future

My partner atCenter for Digital Imaging *, Howard Goldstein, and I have been fortunate to work as consultants toThe Metropolitan Museum of Artin New York since 1995, when the museum first implemented digital capture. The work of the Museum’s photo studio (in continuous operation since 1903) literally represents a history of photography as well as a good gauge of where the industry is headed. The first Met photographers utilized daylight streaming in from the skylights in studios situated over the great hall of the Museum. Over several generations, Met photographers have utilized every photographic process and every light source described above.

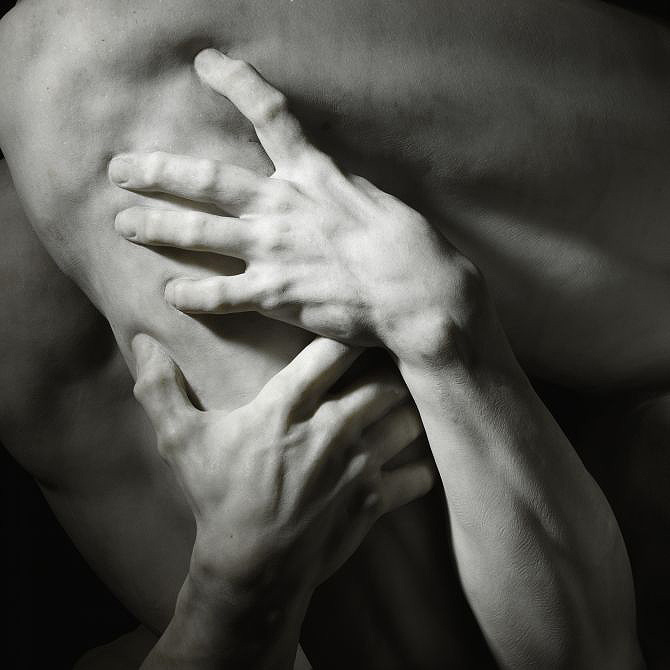

When one looks at the digital photography from the Museum, one assumes that there is considerable Photoshop post-production involved; in actuality, the images you see are created using time-tested traditional lighting techniques. Many of the most stunning Met images are illuminated using a single light source and skillful use of reflectors and fill cards. The play of light across the surface simply cannot be created in Photoshop. The staff photographers of the Museum are true masters of light.

Photography by Joseph Coscia, Jr., Chief Photographer, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A Chance Encounter with Fox Talbot

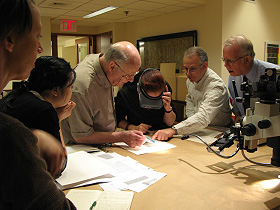

In the Museum’s photography collection is a very rare album of images called the Album di Disegni Fotogenici , more commonly referred to as the “Bertoloni Album” created by none other than Fox Talbot around 1839-40.http://www.metMuseum.org/toah/hd/tlbt/ho_36.37%2825%29.htmYou will never have the opportunity to see this album because these rare photogenic drawings were never fixed and are light sensitive to this day. If the album were shown in a gallery, even in low light, the images would slowly fade or darken. According to Nora Kennedy, head of Photograph Conservation, these salt stabilized prints will not magically recover; the effect is cumulative. The Museum had been researching ways to share this artwork with the public, and been collaborating with experts worldwide on how to safely digitize the album’s photogenic drawings to create facsimiles for study. One of these experts is a chemist named Mike Ware from the UK who has specialized in understanding the properties of these early photographic processes, and has been one of the first to provide concrete guidelines as to light exposure.

Photo (left) taken by Luisa Casella. Pictured from left to right, Hadassa Koning, Hanako Murata, Mike Ware, Nora Kennedy, Malcolm Daniel, Roger Taylor / Photos (right) taken by Nora Kennedy Pictured: Mike Ware,Scott Geffert / Elsec UV meter

Around this time I had been experimenting with the use of LED lights for photographing art with scan cameras. One unique quality of LED light is that it emits very little UV or iR radiation compared to other photo light sources. Part of Mike Ware’s work was to discover whether the Museum’s existing lights were safe to use for imaging the album. Together, we set out to measure the spectral response of various lighting systems in use at the time. None of the studio’s traditional lights were deemed safe due to high UV levels.

We subsequently measured an early CDI LED prototype. I vividly recall having to check the batteries in the meter as it measured a consistent 0 UV. While more sensitive instrumentation will pick up UV in any light source, the amounts relative to other available light sources are considerably lower. For example, even the ambient tungsten lighting in the office registered higher UV readings. Researchers are currently exploring the damaging effects of long-term exposure to LED light within the visible spectrum but when I explained that I was able to flash the LEDs to precisely limit the visible light exposure, Mike and the rest of the team became very excited. After more tests in the US and overseas and a dry run using hand-made lights and facsimile artworks we were able to verify the process. The Museum commissioned my company, Center for Digital Imaging, to build a set of LED lights to facilitate high resolution photography of the entire Bertoloni Album for the first time in decades.

CDI 100 watt LED Flash Lighting

As we sat in a darkened room, the LED lights would silently flash for one second exposing each page, literally uncovering a time capsule. As the digital images appeared on the screen there were “oohs” and “aahs” from Met staff photographer Eileen Travell, along with everyone else in the room. I thought back to Fox Talbot’s first demonstration of electronic flash and I realized at that moment that we were witnessing the dawn of a new era in photographic lighting; the digital LED flash. We could almost feel Fox Talbot’s presence in the room, nodding his approval.

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Fox Talbot, Album di Disegni Fotogenici (Bertoloni Album) William Henry Fox Talbot (around 1839-40) Lacock Abbey / Bromus Maximus, Genoa

A Bright Future:

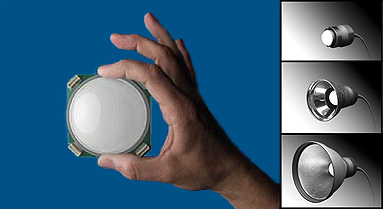

Since this event, I have continued to develop and patent the various methods and embodiments to overcome previous limitations in LED technology and to explore new applications. The latest iterations are a 400 Watt high CRI white and a precision multi-spectral LED module. The concept of multi-spectral is akin to why your Epson ink jet printer uses multiple cartridges to build color. Imagine a light that can use many accessories, has a long life span, is rugged, energy efficient, produces any color in the rainbow, and can be utilized for both film and video.

The CDI 400Watt Multispectral Constant/Flash Light Engine designed specifically for precision digital still and video illumination. Shown in a universal lamp head configuration with standard reflectors.

This capture session was created using a Canon DSLR camera and a single 400watt multispectral light source retrofitted into a standard ProFoto lamphead with a ProFoto portrait dish reflector. Notice the full control of color. Using multi-spectral lighting also opens up amazing black and white control. (©2010 Scott Geffert Model: Staeske Rebers)

If you can imagine all that, you can quickly begin to see why LED is destined to become the light source of the next generation of photographers and videographers. Initially the power output of LED will not surpass studio electronic flash, but this current technology already competes favorably with HMI, fluorescent and tungsten sources and is powerful enough for the new crossover photographers/videographers. Rapid development in LED technology will improve power output to the point where it will rapidly surpass electronic flash in terms of popularity.

When I was experimenting with photographic lighting in my basement as a teenager, I never expected that this interest would take me around the world, allow me to cross paths with the history of photography, and to play an active role in the advancement of photographic lighting. As this technology is introduced to the market either directly by CDI or via lighting manufacturers that have licensed our patented technology, people will begin to be able to take advantage of amazing new creative capabilities. While there will be many LED lighting technologies in the future, I am happy to say that only one has been so closely tied to the traditional roots of the art and science of photography. I wait in anticipation to see the impact of this technology as today’s imagers explore the creative potential of the first lighting technology designed from the ground up for digital still and video capture.

September, 2010

Scott Geffert

Resources and Further Reading

UPDATE-February 2013: Scott Geffert’s LED Flash technology has been awarded a US Patent (8,364,031 B2) . He can be contacted via his web site imagingetc.com.

* UPDATE: Scott Geffert has started a new company:imagingetcto focus on standards-based digital imaging and advanced LED lighting integration. He can be contacted at imagingetc.com.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: metmuseum.org

http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2010/stieglitz-steichen-strand

Read this story and all the best stories on The Luminous Landscape

The author has made this story available to Luminous Landscape members only. Upgrade to get instant access to this story and other benefits available only to members.

Why choose us?

Luminous-Landscape is a membership site. Our website contains over 5300 articles on almost every topic, camera, lens and printer you can imagine. Our membership model is simple, just $2 a month ($24.00 USD a year). This $24 gains you access to a wealth of information including all our past and future video tutorials on such topics as Lightroom, Capture One, Printing, file management and dozens of interviews and travel videos.

- New Articles every few days

- All original content found nowhere else on the web

- No Pop Up Google Sense ads – Our advertisers are photo related

- Download/stream video to any device

- NEW videos monthly

- Top well-known photographer contributors

- Posts from industry leaders

- Speciality Photography Workshops

- Mobile device scalable

- Exclusive video interviews

- Special vendor offers for members

- Hands On Product reviews

- FREE – User Forum. One of the most read user forums on the internet

- Access to our community Buy and Sell pages; for members only.