Almost exactly a year ago, Apple made a radical break from 15 years of using Intel processors in Macs, bringing a number of low-end Macs (MacBook Air, Mac Mini and 13” MacBook Pro) over to what they call Apple Silicon – a higher-powered version of iPhone and iPad processors. The original M1 Macs are extremely strong performers for what they are– nobody had ever seen an ultra low power notebook run that fast. On the other hand, they are still low-end computers with some limits. Most notably, they only support 16 GB of RAM, and they have limited display support (without some hacks, they support the internal display plus one external monitor). The original M1 looked suspiciously like a souped-up iPad CPU, with a claimed 8-core design – but four of them were low-power “efficiency” cores. Apple later confirmed that it WAS, in fact, an iPad CPU, by releasing the 2021 iPad Pro with the same chip.

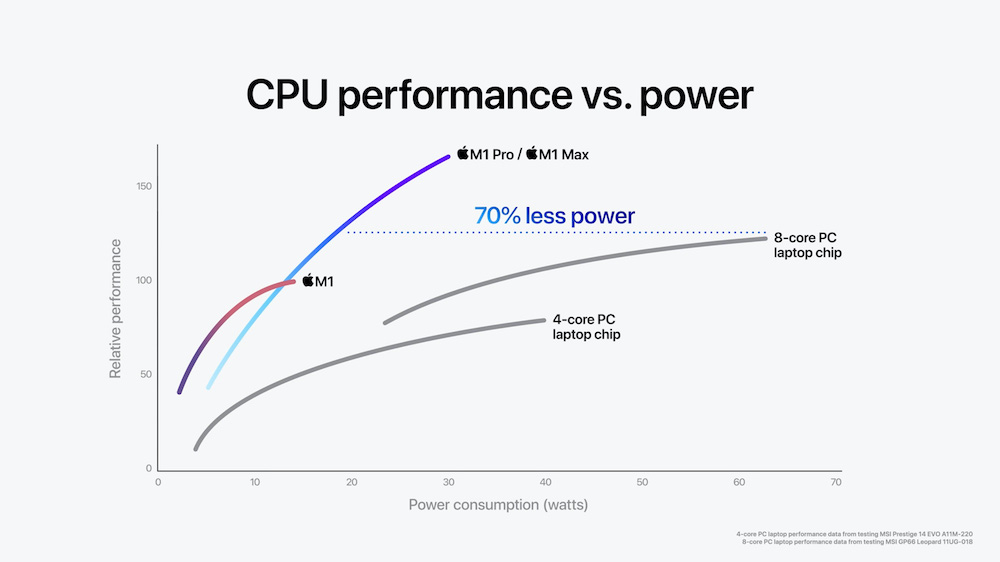

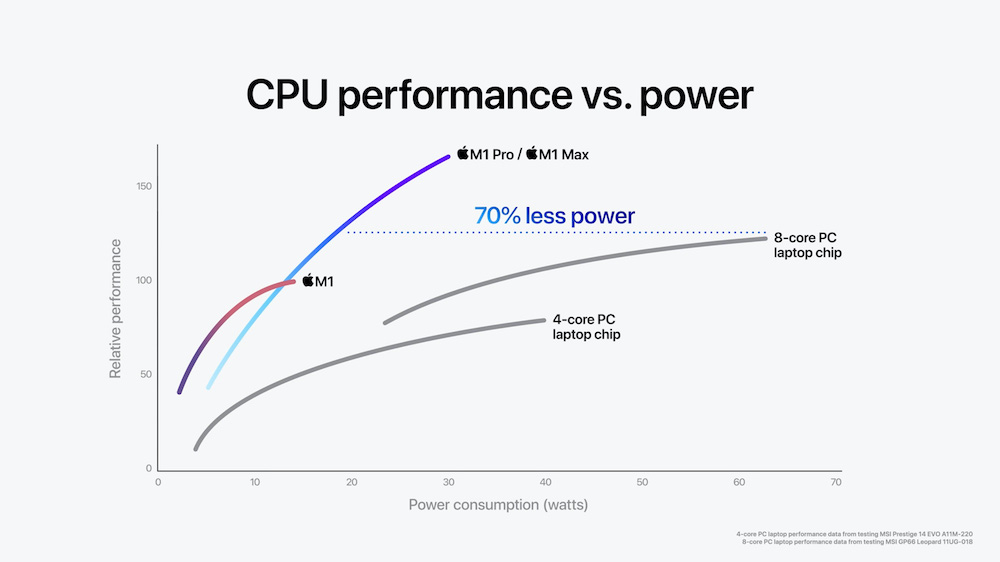

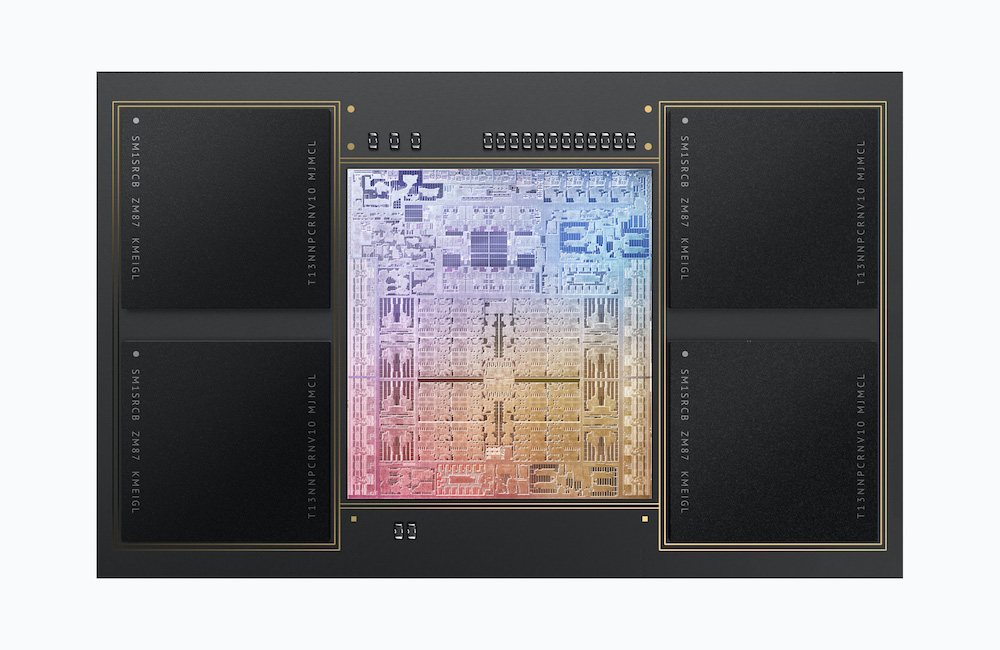

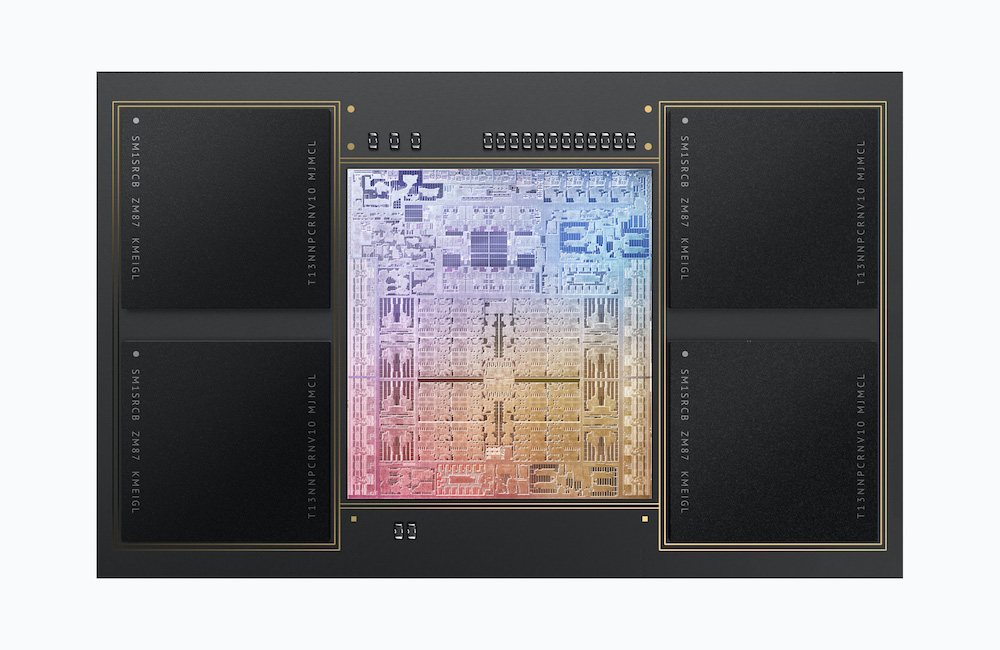

Even with the low-power CPU, the M1 Macs were remarkable performers, good enough to cause a lot of professional users to wonder “what if Apple released a less power-constrained version of that chip”. If a little mini notebook with an iPad chip running under 10 watts could perform like a 16” MacBook Pro, what would happen with a 40 watt chip based on the same technology? What would a machine with the best of Apple’s professional technologies and a bunch of Apple Silicon cores look like? Today’s introductions, new 14” and 16” MacBook Pros using two new Apple Silicon chips, begin to answer that question. Both new Apple Silicon Systems on a Chip (SOC) use very similar CPU and GPU cores to the original M1 – but there are a lot more cores, and the ratio between performance and efficiency cores is different. The smaller of the two SOCs, the M1 Pro, comes in two varieties with different numbers of CPU cores, and is available with 16 or 32 GB of RAM. It has 14 or 16 GPU cores, as opposed to 7 or 8 on the original M1. The CPU core choice is between 8 and 10 total cores. While the original M1 also claims to be an 8-core chip, it has only 4 performance cores (and 4 efficiency cores). Even the low core count variant of the M1 Pro has 6 performance cores, losing two efficiency cores for two more performance cores. The 10-core version has 8 performance and 2 efficiency cores.

The M1 Max is the M1 Pro’s big brother, always coming with 10 cores in the 8 performance core configuration. The two key differences between the M1 Pro and M1 Max are that the Max has 32 and 64 GB memory options (no 16 GB option, but 64 GB is available) and that the graphics options are 24 and 32 GPU cores. Geekbench scores for the highest performance version of the M1 Max have leaked, and the single-core score is very similar to the M1, around 1750, as one would expect given that the performance cores are very similar if not identical. The multi-core score is around 11500, roughly 1.5x the score of any M1 Mac or the fastest 16” MacBook Pro. There are very few if any laptops other than the new MacBook Pros that Geekbench over 10,000. Even a desktop Core i9-11900 is barely faster. The only systems short of Xeons and Threadrippers that can beat that Geekbench score are some of the desktop Ryzens with their high core counts.

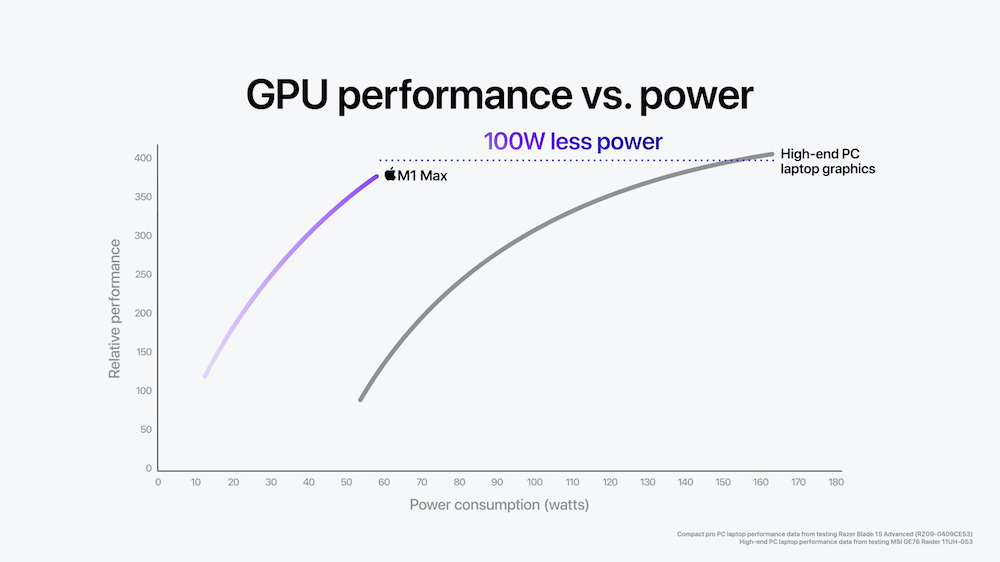

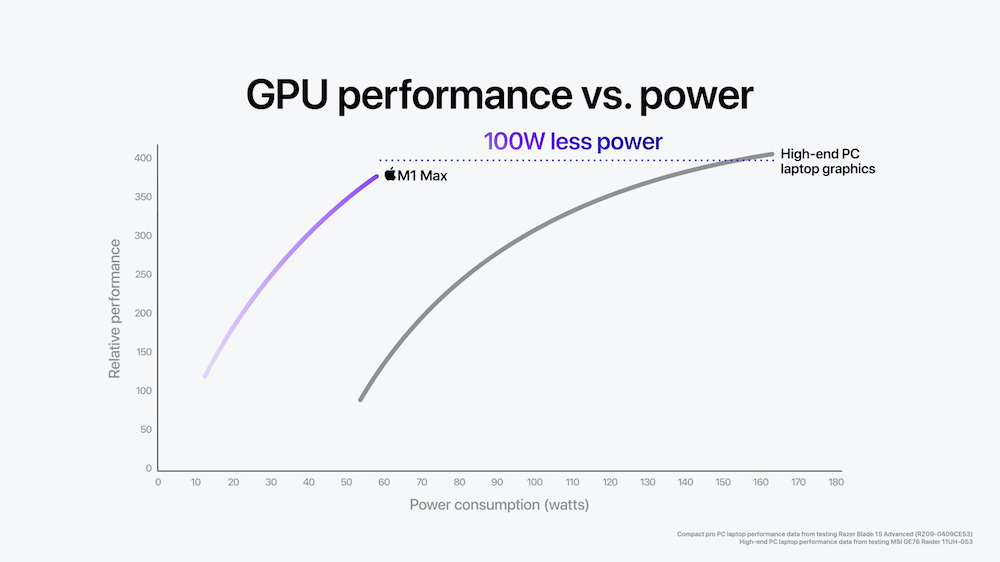

Estimated graphics performance numbers are equally impressive. Assuming that the GPU cores are similar to those on the original M1, 32 of them should perform something like a desktop Nvidia RTX 2080 or a PlayStation 5. The same 32 GPU core version should be slightly more than twice as fast as the Radeon Pro 5600M that is the fastest GPU option on the 16” Intel MacBook Pro.

One unusual feature of the M1 Pro and M1 Max is that they are so power-efficient that even the most powerful version of the M1 Max is available in the 14” MacBook Pro. Apple decided not to make a version with even more cores that needs the power and cooling of the 16” chassis. Throughout the recent history of the MacBook Pro, the small chassis has had significant performance disadvantages – fewer CPU cores and no discrete graphics. Now, the most powerful CPU and GPU are available in the smaller chassis. The small chassis has more CPU options than the large one, because the lower-end 8 CPU core, 14 GPU core version of the M1 Pro is only available in the 14” model, presumably to slip a new MacBook Pro in under $2000 (the lowest-end model costs $1999).

Beyond the raw performance, which should be excellent, the new MacBook Pros offer a number of interesting features. The headline feature is the Mini-LED display technology we first saw in the ultra-expensive Pro Display XDR, with similar brightness and color gamut. Apple is claiming the same 1000 nit sustained/1600 nit peak brightness as the Pro Display, and they are referring to it as an XDR display. Of course, nobody’s seen the new notebook display live, but it should be impressive. It is supposed to cover the DCI-P3 color space, which suggests (but no confirmation yet) that it should cover a very high percentage of Adobe RGB as well, since the two color spaces are very similar. Apple is claiming a billion colors, which suggests that it’s a 10-bit panel, something normally only seen on high-end professional monitors (the only other 10-bit laptop I’m aware of is HP’s Dreamcolor displays).

The screen resolution also improves from 3072×1920 to 3456×2234 pixels on the 16” model. The 14” model gets a 3024×1964 pixel display (the older 13” was 2560×1660). A few pixels at the top of the screen are lost to an iPhone style notch, a necessary tradeoff for the nearly bezel-free design, The notch is designed to fit between the menus and the menu bar icons, where it will cause as little trouble as possible – be careful if you use iStat Menus or something else that has a ton of icons…The original M1 would only drive one external display, while the M1 Pro will drive up to two 6K (or smaller) displays plus the internal display and the M1 Max will drive three displays up to 6K, one up to 4K and the internal display (no word on 8K displays, but I suspect the M1 Pro will probably drive one and the M1 Max might drive up to two).

One potential challenge is calibration – the similar Pro Display XDR can only be calibrated using very expensive instruments – Datacolor Spyders need not apply. The good news is that the display is factory calibrated and good LEDs don’t tend to drift much. Most users of the Pro Display XDR probably don’t own the multi-thousand dollar instruments necessary to calibrate it, and we don’t hear of those drifting impossibly. It is an impressive achievement on Apple’s part to cram as much of the performance of the expensive, specialized Pro Display XDR into a laptop as they seem to have.

Many photographers will be happy to see the return of the missing ports. Instead of four USB-C/Thunderbolt 3 ports and nothing else, we now have three USB-C/Thunderbolt 4 ports plus a MagSafe charging port (reconfigured so it isn’t nearly identical in size to a USB port – old MagSafe cables used to stick to random USB ports). In addition, the two most requested legacy ports are back – full-sized HDMI and an SDXC card reader. Unfortunately, there is no XQD/ CFExpress reader (although, to be fair, I can’t recall a laptop from any maker with one built in), and there is no legacy USB port for random memory keys and ImagePrint dongles. Overall, this port arrangement is significantly preferable to the one we’ve suffered with since 2016 – there are still quite a few very flexible Thunderbolt ports, but two of the three most common reasons for dongles are taken care of. Except for VERY old VGA-only projectors, the new MBPs will project in any classroom or conference room without an adapter – something that can only be said of a very few Macs over the past two decades. They will also read memory cards from most cameras in use today, although the absence of a CFExpress reader leaves out a fair number of newer pro cameras, or limits the built-in reader to the less capable card on those cameras.

Apple’s charging solution is excellent – the new MacBook Pros will charge over either MagSafe or USB-C. The 16” model ships with a 140 watt USB-C adapter and a USB-C to MagSafe cable, which will also work with other USB-C chargers if you have a favorite high-power multiport charger. It will also accept power through any of its USB-C ports without using a MagSafe cable – handy for single-cable charging from monitors, docks and the like. It will charge to 50% in 30 minutes using Apple’s adapter and cable, and might using certain other combinations. High-power USB-C charging (beyond 100 watts) is tricky enough that I wouldn’t count on any combination other than “Apple 140 watt adapter/Apple MagSafe cable/MagSafe port” working right away. The standard for charging beyond 100 watts is only a few months old, and most older high-power USB-C chargers are nonstandard – they’ll charge one particular piece of equipment very fast, but look like 60 or 85 watt chargers to everything else. Apple’s implementation is claimed to be standards compliant, so any charger and cable rated to 140 watts under the new standard should run at that rate, and any standard charger that can do 140 watts should accept the MagSafe cable for 140 watt charging.

Apple claims audio improvements, as they do on every MacBook Pro redesign. They’re usually right, and any recent MacBook Pro sounds pretty good for a laptop. This one may be better – probably is, but still unlikely to be as good as decent external speakers. One improvement that IS probably real is that they’ve FINALLY replaced the extremely tired 720p webcam with a 1080p model. There’s a new keyboard that dispenses with the unpopular Touch Bar and returns a regular row of function keys to the top of the keyboard. Hopefully it’s at least as good as the Magic Keyboard on the 2019 models – Apple makes no claim so far as to whether it is the same mechanism or something different.

Overall, it seems to be a very solid design. I’ve requested a review machine, and look forward to trying it out. If the performance figures hold, it should be the best-performing laptop around for general-purpose and creative professional tasks. A few Windows gaming laptops with very high-end GPUs may beat it for certain GPU-intensive tasks, but they will have significantly less CPU power. High-end Windows gaming laptops are also notorious for poor battery life, while Apple claims an amazing 14 hour battery for the 16” MacBook Pro in wireless web browsing (low power consumption, but many office tasks are actually lower). They claim it’s so thermally efficient that it runs fanless much of the time.

There are a few unanswered questions… First, could they have built an even faster 16” laptop? Since even the fastest M1 Max fits within the power and thermal envelope of the 14”model, and since the 16” model is often capable of running fanless, they seem to have quite a bit of thermal headroom on the larger model. What would a 14-core CPU with 12 performance cores have done? There’s even a possibility an 18-core CPU sporting 16 performance cores could have worked… Like all of the M1 family, these machines are at once groundbreaking and oddly conservative. Apple consistently uses their performance per watt advantage to build a very fast computer, but they don’t seem to push it to the edge of the room they actually have, settling for “very fast with unbelievable battery life”, when “extremely fast” could have been possible?

The second question is whether we’ll ever see a computer specific Apple Silicon CPU core. They don’t confirm it for sure, but these cores look suspiciously like the same ones used in the original M1, which are also found in the A14 Bionic chip in the iPhone 12. An M1 is more or less two A14 Bionics, and the M1 Pro is closely related to three or four A14 Bionics (depending on the configuration), although without continually increasing the number of efficiency cores. Will we see a Mac Pro that is pretty much 16 or 32 iPhone chips, or will Apple build a unique core for less power-constrained applications? We might have seen a unique core here, but didn’t…

The final question is what will happen to the top of Apple’s lineup. Apple Silicon now extends from the cheapest Mac Mini to the 16” MacBook Pro. The only two machines left (barring something new like a high-performance Mac Mini) are the larger, higher-performance iMac variant and the Mac Pro. Just as the original M1 was groundbreaking in the MacBook Air but disappointing in the 24” iMac, the M1 Max would be a disappointment in a 27” or 30” iMac and a HUGE disappointment in a Mac Pro.

The fastest current 27” iMac benchmarks almost as fast as the M1 Max and supports twice as much RAM. The 27” iMac can cool a couple of hundred watts – if Apple sticks a 40 watt chip in it because they happen to have one around, it will be a significant letdown compared to what it could have been. The larger iMac chassis could easily support a stunningly fast 26 core M1 style chip with 24 performance cores and 2 efficiency cores, coupled with 64 or even 128 GPU cores – will Apple build that monster? Or will we see an iMac that is effectively a 14” MacBook Pro with a huge screen? 64 GB is a tremendous amount of RAM in the 14” chassis, twice as much as most competitors cram in a machine that light. It’s acceptable in the 16” chassis – nobody gets more in a midsized laptop, but it’s a standard option across most high-end 15” and 16” laptops. It would be disappointing in a desktop whose predecessor supported 128 GB, when most high-end desktops support 128 GB.

The situation with the Mac Pro is even more extreme. The current model supports up to ~300 watts of CPU power, a kilowatt or so of GPUs and 1.5 terabytes of RAM. If the M1 Max were to make an appearance there, it would be laughable – the big Xeons and Radeons in the current Mac Pro are significantly faster. Apple will probably need to break free of SOCs here, building a chip using (a ton of) similar cores that is really just a CPU. They can use their own GPU cores if they want to, but there had better be a lot of them, enough that they probably need to go on a separate chip (or several). They need to provide expandable RAM, abandoning the fast but limited unified memory (or using unified memory to cache the slots).

We’ve now seen Apple Silicon in the midrange, and software is catching up. Many of the applications we rely on as photographers are native, and the rest are probably coming. Lightroom Classic, a potential holdout, was featured in today’s presentation. The technology is stunningly fast for the low power consumption, but we have yet to see a no-holds-barred Apple Silicon Mac. Apple let the brakes off substantially with the latest announcement, but they didn’t go all the way – the 16” MBP could have taken a bigger chip, one not constrained by the 14” MBP, even as the one it got makes it almost certainly the fastest all around laptop in the world. We still haven’t seen Big Apple Silicon – we don’t know where the limits are.

Dan Wells

October 2021