My favorite works of art make you pause to examine, question, and ponder. Not necessarily as a means of getting profound life lessons, but work that simply makes you think. It is a special treat when there is also the opportunity to talk to the artist behind works that do just that. Those conversations can deepen the understanding of the work and also bring up new assessments and considerations.

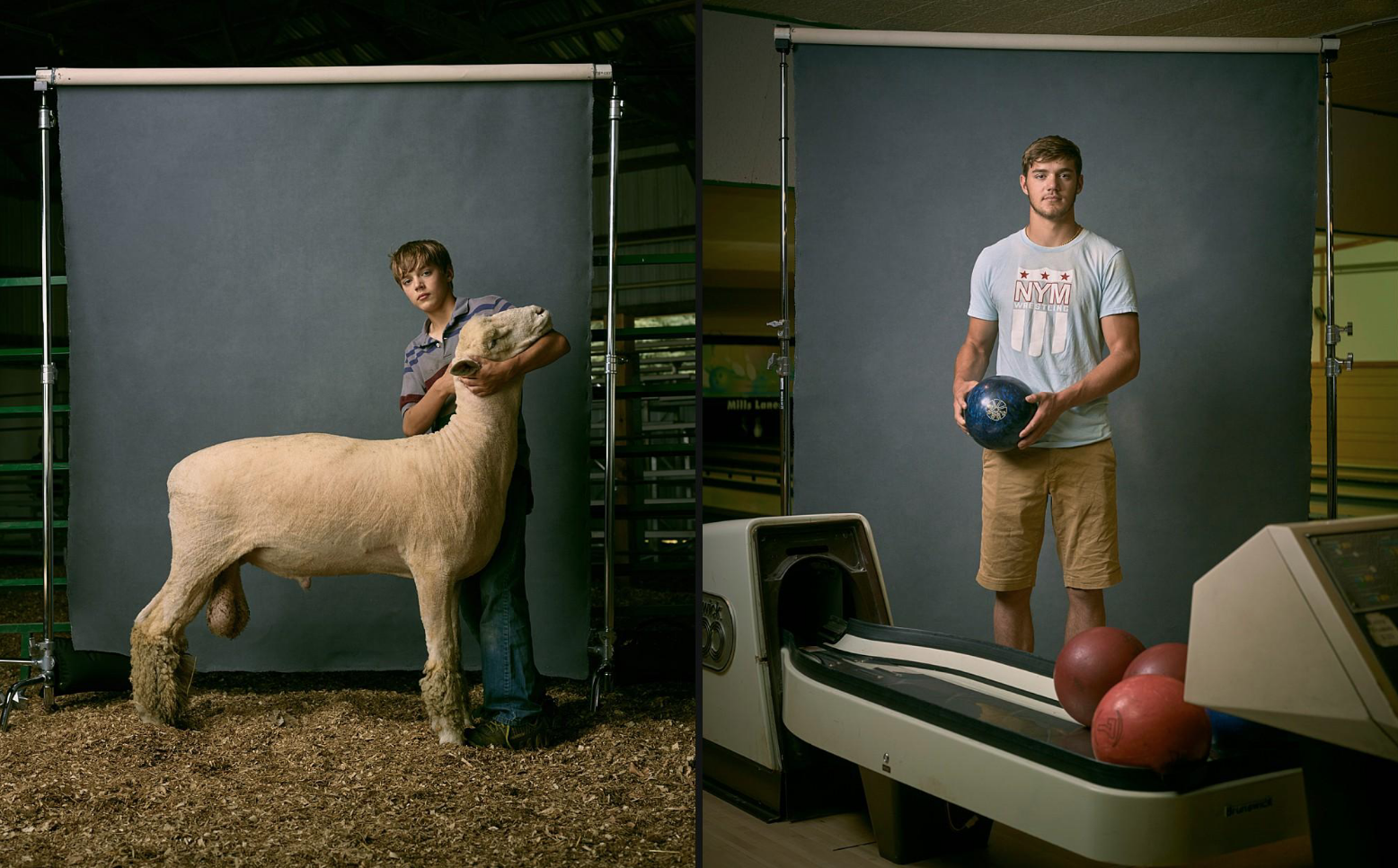

I’ve now had the privilege of two separate occasions to chat with artist and photographer R. J. Kern, once in person and once via Zoom. In both instances, I learned new things about his process and orthodox, or simply the reasoning behind his photographic decisions and the images found in his new book, The Unchosen Ones: Portraits of an American Pastoral.

Thoughts on Technique

Much of R. J.’s technique and style can be traced back to where he finds inspiration, in 19th-century paintings. The colors, lighting, and general mood found in paintings by artists such as Charles Émile Jacque, Thomas Sidney Cooper, and Adriaen van de Velde can also be found in R. J.’s photographs.

However, at the same time, he clearly draws a distinction in his work from paintings.

“There’s a difference between looking at a painting of Abraham Lincoln and Mathew Brady’s photograph. We remember the images, his actual face in the frame. This exactness makes it captivating, enthralling. It’s not a painting. It’s real. It’s a photograph. That detail is important.”

To aid in capturing detail, R. J. shoots with a Phase One medium format camera. From the inception of this project, he envisioned the photographs being printed large, almost life-size. He has been inspired by artists like Alex Soth and Rineke Dijkstra, who shoot with 8×10 view cameras; the resulting prints from large and medium format cameras have a real-life quality that wouldn’t be possible with a standard DSLR. Even when the prints are smaller, the detail from the medium format camera comes through. I love how R. J. further explained the importance of detail and the difference between photography and painting:

“Maintaining detail in portraits is critical. We look at photographs differently than paintings. With paintings, we step back. With photographs, we step forward, peeping at every pixel. With smaller formats, details break down. With larger formats, there is always more to see. Which is one of the reasons I favor medium format cameras.”

Lights as an Asset

Clearly, lighting is a crucial component of R. J.’s work. So when he set out on this new series, he knew that the use of artificial light would be significant for various reasons. I really enjoyed the way he put the general thought process behind using artificial light:

“When I first met the kids, I promised to put them in the best light possible, literally and metaphorically. It was key to the project in earning trust. When you have strobes set up with C-Stands, and it’s like a little set, people are like, ‘Oh! You’re professional!’ There is this level of trust that very quickly helps to build rapport.”

So the lighting is about building trust, but it goes beyond that as well. R. J. said that,

“I like the mindfulness of slowing down as well. Being very intentional like ‘this is where we are going to shoot.’ It commits me as opposed to running and gunning. It slows me down and allows me to think.”

That statement above by R. J. is crucial for photographers, especially fine art photographers, to keep in mind. It is extremely easy to fire off a handful of shots with modern cameras and move on to the next thing. Or even using the spray and pray method of photographing with a camera with a high number of frames per second and taking a handful of images at once, hoping that one or more is sharp and composed well enough.

The simple act of slowing down can make such a tremendous difference in the quality of your work. If there is one thing you take away from this article, let it be that.

Color as a Creative Decision

When flipping through The Unchosen Ones, you may notice that some diptychs have pretty different color temperatures between the two images. R. J. was intentional in doing this, explaining that,

“Color is one of those creative decisions photographers have. We read images differently that might be cooler or warmer; they have different feelings…In 2016 I really wanted to make sure that everyone had a unique look. I didn’t want them to look like mug shots.”

He went on to tell me that he also wanted to make sure that each individual image stood on its own, apart from the diptych. At times this required that he go with a different temperature and mood for the photograph taken in 2020. He was very much reacting to the environment, to what his subject happened to be wearing or surrounding themselves with. Part of that decision also relates to the style that he aims for:

“I don’t want something overly slick and cool. I like raw and messy. Yet, I do love the idealized. Flattering light helps with this; however, you don’t want too much of a polished portrait. My hope is to create a photograph that does more than reference a classical portrait — I want to raise the ante. When people are in front of a camera, there is a realness, an authenticity. This is a hallmark characteristic of a photographic portrait— it’s not just a pictorial reference of the person— it IS the person.”

Color and Light

Color is also important with lighting, which may seem counterintuitive. Going back to R. J.’s inspiration, if you look closely at those 19th-century paintings, you will notice how rich and complex the light is. Another one of R. J.’s influences on light, photographer Greg Heisler, has talked about how artificial light needs to contain different colors to look natural. Using only white light comes across as sterile and not lifelike. As R. J. puts it,

“When you rely on the easy, fake happens. People see artificial light too easily. The goal of a photographer is to messy it up so it looks natural.”

If you look closely at the world around you, you will notice sunlight has a color depending on the time of day and even the time of the year. Then on top of that, the environment will reflect light around, casting colors and muddying things up. For example, if you pose a portrait subject next to a tree on a gravel road, the tree’s green will reflect onto their face, leaving a green cast on one side, most likely in the shadows. There could also be a warm light reflecting up from the gravel. The range of color being bounced around will be vast and complicated.

So in order to reproduce the complex mix of color in real-life light, R. J. uses gels to add both warm and cool colors to different parts of the images. One crucial part of this is that the shadow areas always need detail. If you look closely, there is no pure black in his images. Pure black shadows would not take color the same way, so keeping detail in the shadows is essential. In fact, R. J. does most of his color work in-camera, largely by using artificial light in particular ways, and only minimally adjusts colors in editing.

Big Lights, Far Away

Beyond using strobes for color, he also uses them to create a certain quality of light. Generally speaking, R. J. sticks to a three light setup with lights on the left, as that is how our eyes read light. As you can see in the images in his book, he uses big lights that are set up a ways away from the subject. I thought his advice for using artificial light was intriguing:

“Light gets even more beautiful when it is bigger than your subject—there’s luxury! That is why car photographers use lights and diffusers the size of a semi! If you want to create light that is awesome, use the biggest light you can find. Sometimes that can be from reflective light bounced off a wall with the sun. But, indoors, that is tricky.

Sometimes that is a bounced light. Sometimes it is a softbox or light diffused by a scrim. It doesn’t have to be the brightest. It has to mimic large north-facing window light that painters love, which is soft, diffuse light.”

The thing that stands out in the statement above is that it doesn’t have to be the brightest. It is easy to fall into the mindset that your lighting has to be bright to make really dramatic, exciting light. But that isn’t necessarily the case, as R. J. shows.

Environmental Portrait

Perhaps my favorite thing in The Unchosen Ones is the inclusion of background or setting in some capacity in all images despite also using a backdrop. Some photographs show just a hint of the surroundings, whereas others present an expanse of farm beyond the set. R. J. and I talked about how in this way, his work falls within the realm of environmental portraiture, a very purposeful move for this series. The environmental portrait does a few things, but part of the thought process was this:

“Arnold Newman invented this language of the environmental portrait process. Big art, small person shakes up our notions of scale in a situation. It gives context, place.”

While the first round of images in 2016 had some surrounding context visible, it was pretty minimal. It gave you a hint, but nothing more. The broad, pullback shots were something that he started about halfway through the second round of shooting in 2020. He told me that he,

“Put on a 55mm lens and literally walked 150 feet behind just to take it all in. And I’m like, oh, that’s cool!”

So although those images started because they looked interesting and he hadn’t seen them done before, their importance to the series became apparent later. Part of the driver for this body of work is highlighting the importance of these farms, the human connection with animals, and the potential future stewards of American agriculture. These pullbacks then have even more significance, as they give insight into the place behind the animals and the individuals caring for them. It adds to the story in a way that the closer shots cannot.

In our first interview, one thing that R. J. said in response to my question about why he is drawn to farms and 4-H competitions has stuck with me:

“In my own idealized world, I long for sweetness, something like heaven—a place filled with the innocence of childhood and the support of a strong community. A place that exists between the real and the imagined. As an outsider to daily agricultural life, I was influenced by preconceptions about that world. I want my photographs to capture the ephemerality of youth amid the often harsh realities of rural life.”

R. J.’s pullback photographs that show his whole setup along with the scene around it explore this idea of the real versus imagined or idyllic. At first glance, it looks like a staged set, but then you see some of the farm’s messiness and get a snippet of real-life happening behind the scenes. I appreciate how R. J. talks about his process on location:

“When I meet many of these youth, I see what is there first. There is usually a logic to the messiness, even though I may not understand it. My goal is to embrace it. Often, I don’t start from scratch. I use what is in the surroundings. Those lighting conditions are scenes I’ve experienced before in my Rolodex of lighting scenarios in my head. These leave an impression, and I take cues. Often, I won’t rely on the ambient light— yet I am inspired by what I see as a starting point.”

Parting Thoughts

Whenever I read an article about an artist or even have a conversation with an artist, I always hope for some worthwhile thing that I can take away from it. I selfishly want some little nugget to inspire me or change how I look at things, at least in some small way. That has happened in both conversations with R. J., and I hope some of them came through here.

You can read more about R. J.’s newest book and even purchase a copy for yourself on his website. Also available is the Collector’s Edition, which includes two limited edition prints and a custom print folio handmade by the artist himself.

Abby Ferguson

December 2021