John Benigno is a Luminous Landscape Grant winner.

First, I want to extend my sincere thanks to The Luminous Endowment for Photographers for awarding me The Luminous Landscape Grant to continue to pursue my Adobe Church Project. Without this support, I would not have been able to stay in New Mexico for an extended period.

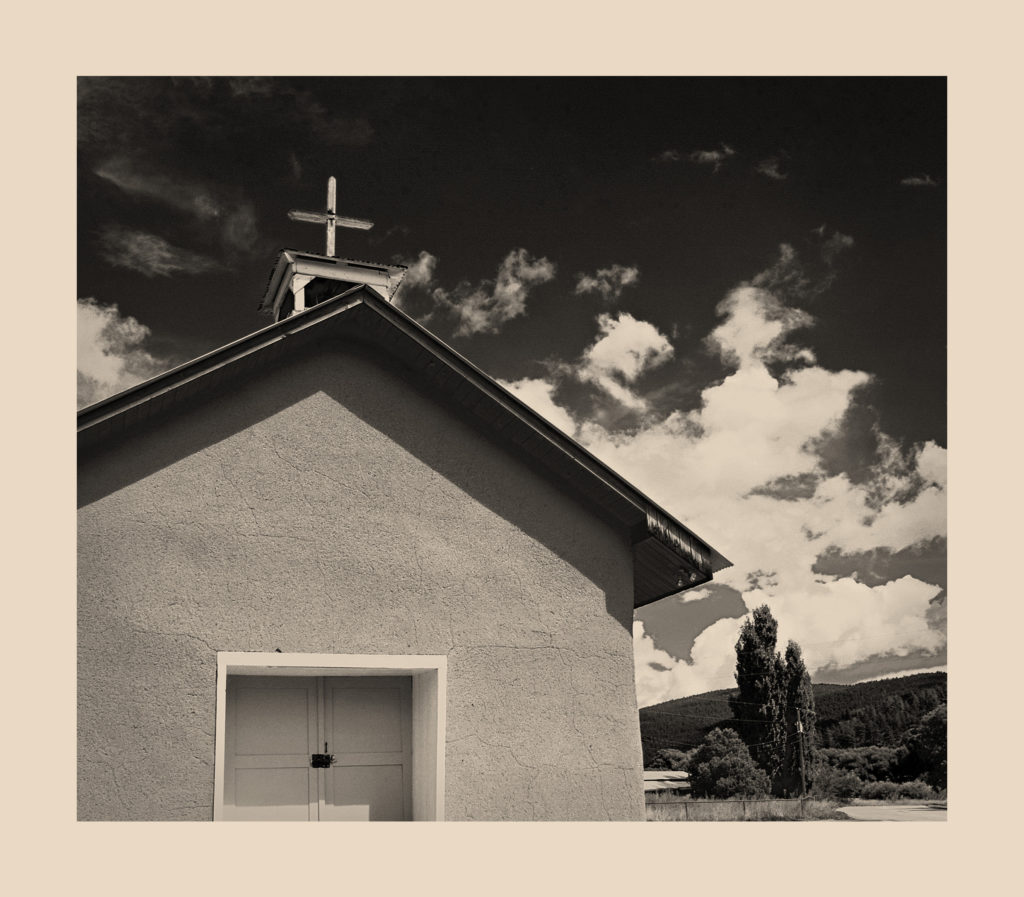

A modest sentence quoting Lewis Hine is the inspiration behind my Adobe Church Project – “I want to show things that should be admired.” I would add to this my own thought – I want to photograph things that should be preserved.

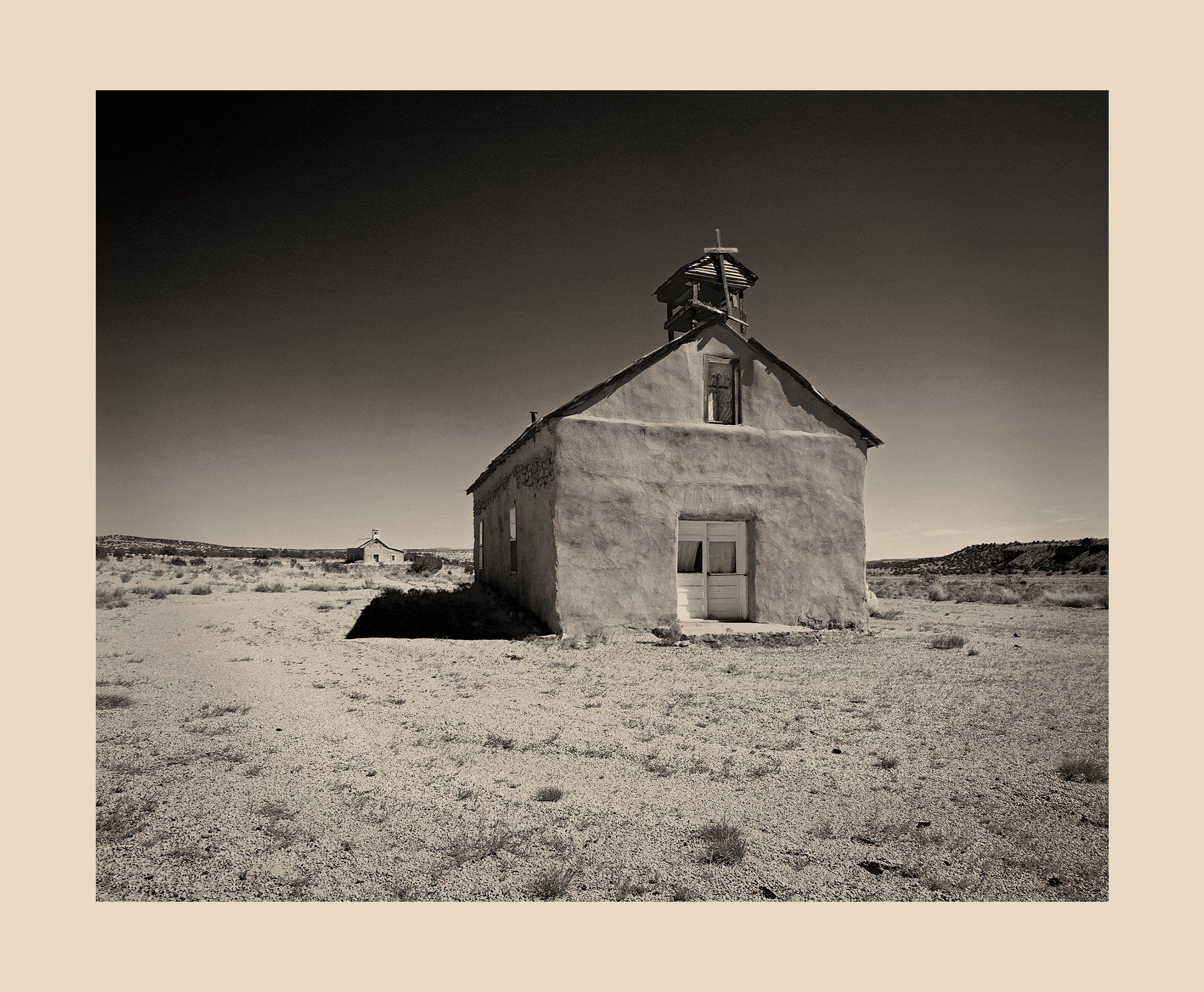

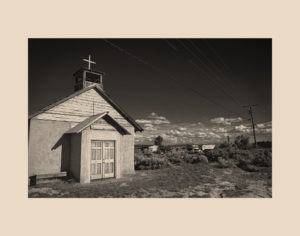

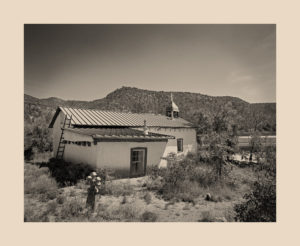

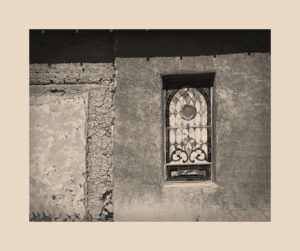

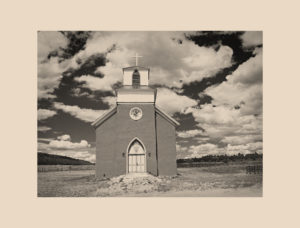

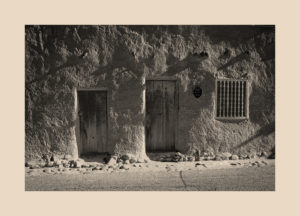

My quest began back in 2004 with a simple idea. I wanted to photograph as many adobe churches as possible while they were still in their traditional state — covered with both mud and straw or lime plaster.

With every visit to New Mexico, I became more and more aware of a dramatic shift in population from rural hamlets, villages, and pueblos to urban centers. With this shift came the loss of a workforce and the skills, as well as the traditions, which went into maintaining the hundreds of adobe churches found in isolated communities throughout the state.

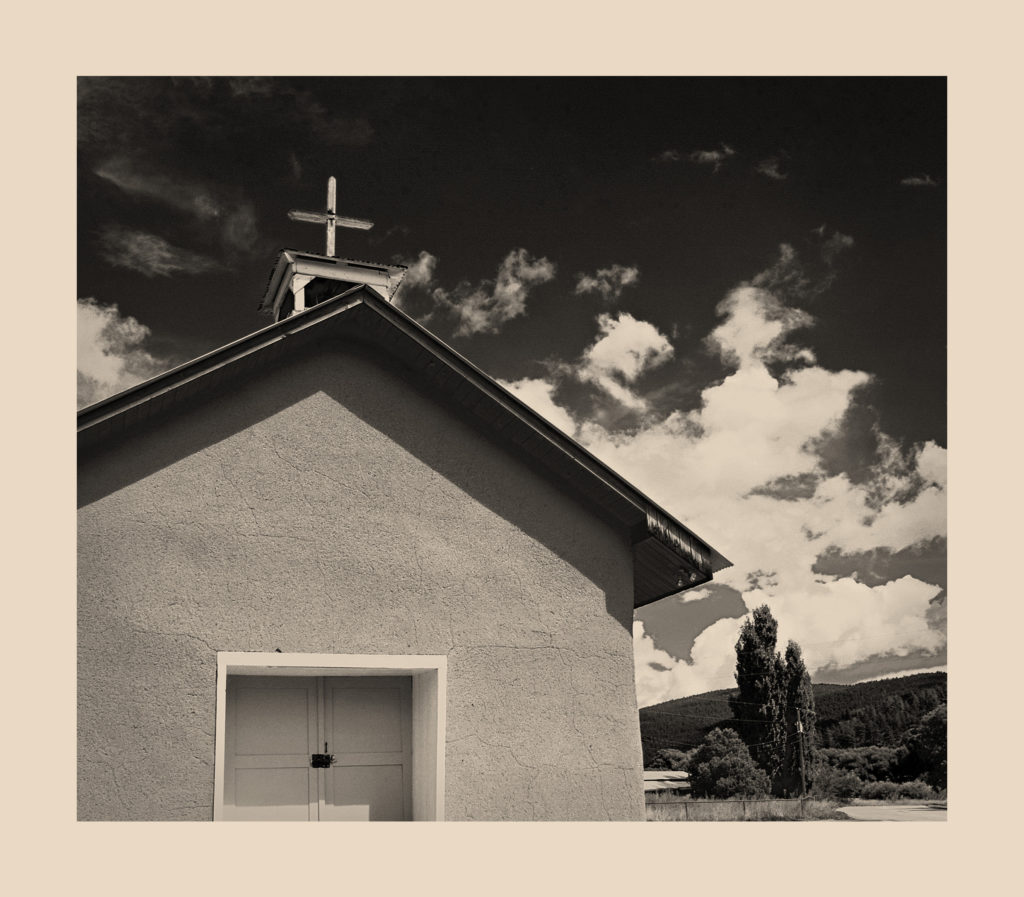

The result of this shift was that many traditional adobe churches had fallen into disrepair, were covered with modern building materials such as stucco, or were replaced with modern structures.

AN ASIDE ABOUT STUCCO: It was hoped that stucco could be the answer to the problem of a dwindling workforce and the ongoing maintenance demanded when using traditional mud and straw or lime plaster. Unfortunately, while stucco did work much of the time, its use wasn’t always successful.

There is nothing wrong with stucco – if it is applied properly. However, because stucco does not breath, if water seeps through the tiniest opening it cannot evaporate. The trapped water eventually erodes interior adobe bricks causing inside walls to crumble.

The two most dramatic examples of this are the San Miguel Cathedral in Socorro where the roof collapsed and the San Antonio Church in Questa where an entire wall came down.

The second problem with stucco is that it simply does not offer the same aesthetic as traditional exterior coverings. Adobe churches are built from earth and faith. Caring for them expresses the fidelity of parishioners to their church. I have nonmeasurable proof of this, but, from conversations with parishioners who would often ask me why I was photographing their church, I’ve come to sympathize with those who felt that the use of modern materials had distanced them from long-standing traditions and rituals.

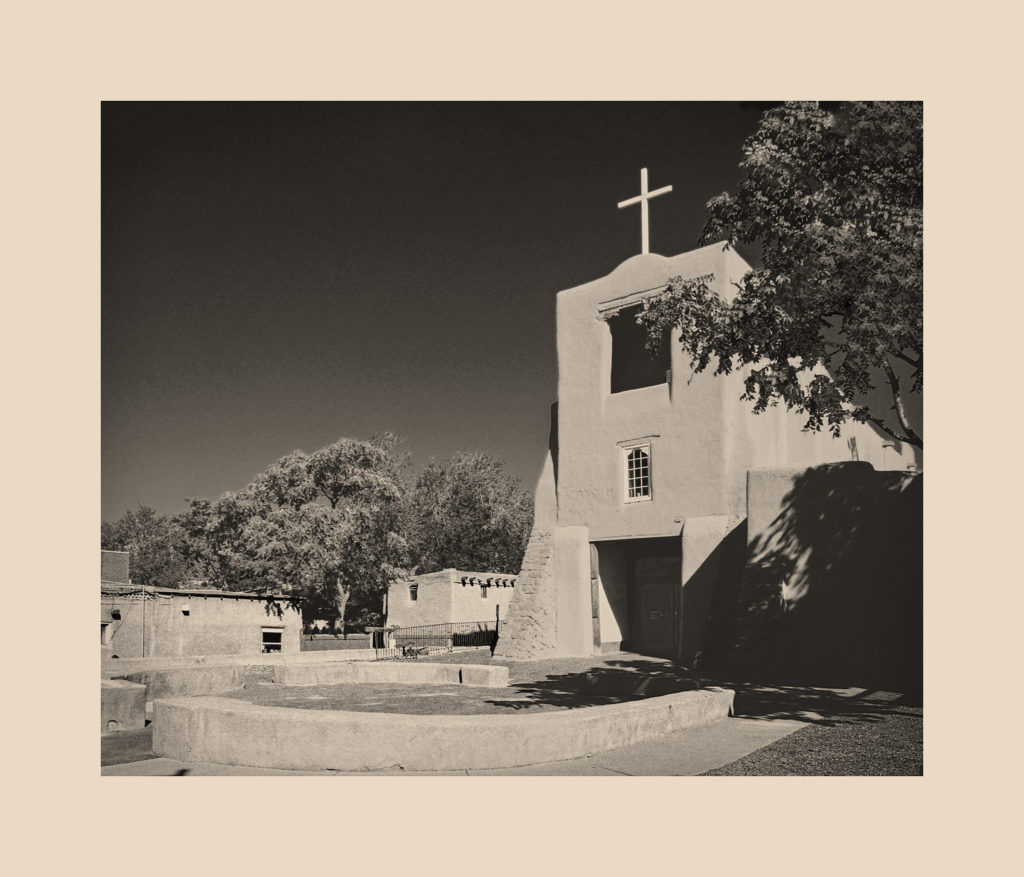

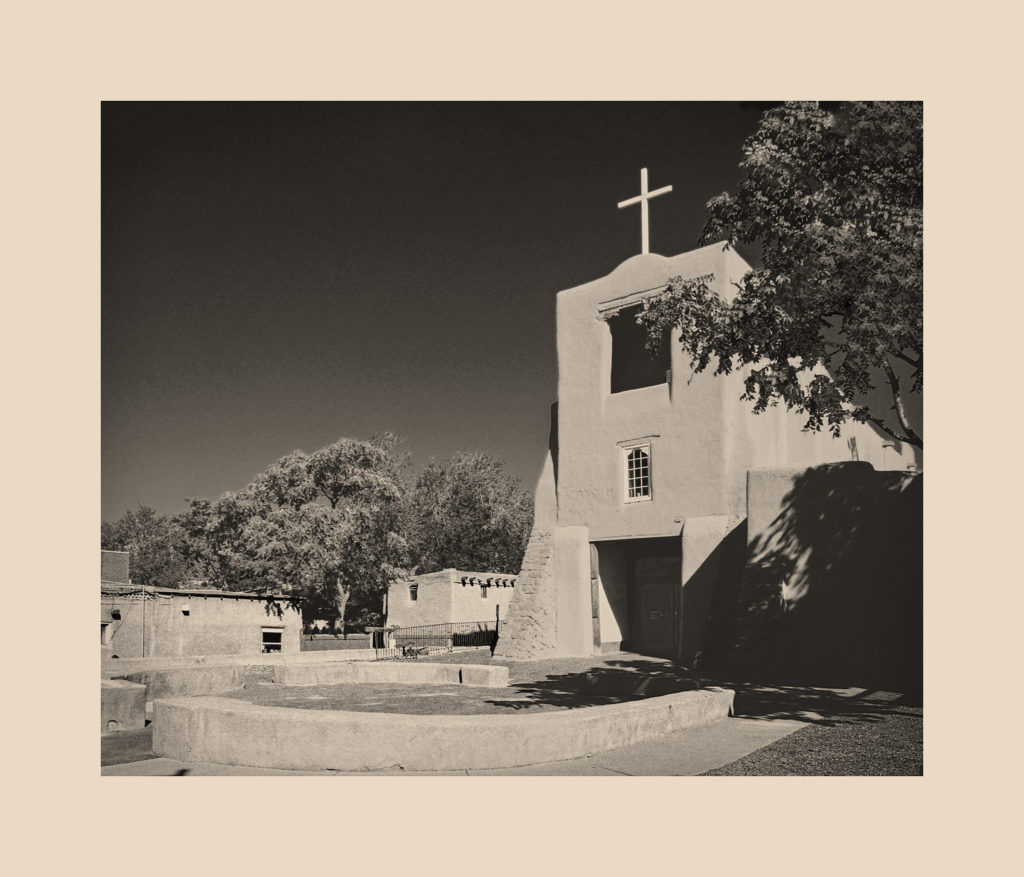

Two examples of this are the San Miguel Mission in Santa Fe and the San Francisco de Asís church in Ranchos de Taos. Both parishes elected to go to the considerable expense to remove stucco exteriors and replace the stucco with traditional mud and straw.

My motivation and passion for this project sprung from my own family history and my interest in the social sciences.

In the early 1900s, my ancestors came to the United States from southern Italy. They settled in Corona – a small section of Queens in New York City.

I have fond childhood memories of visiting my grandparents, going to Sunday Mass with them in the small chapel where priests celebrated Mass in Italian and attending the many saint day festivals steeped in traditions from the Old Country.

I grew older and witnessed these traditions slowly fade away. Typical of many families, my parents moved to the suburbs, the older generation passed on, the little chapel disappeared, and the festivals all but vanished.

By now, you are asking what all this has to do with adobe churches.

While I first visited New Mexico in the early 1990s, I did not start my adobe church project until 2004. However, with each subsequent visit, I would see striking changes – especially when it came to the adobe churches. When I would inquire about this, the answer was always the same — there simply were not enough skilled workers remaining in the small towns and villages where the remaining churches were located and the cost of a new mud job every few years was prohibitive. The result was that the rituals and traditions of maintaining them began to fall by the wayside.

This is exactly what happened within the little Italian community of Corona. Well, while I couldn’t stop “progress”, I vowed to use photography to document the remaining “traditional” adobe churches before these, too, disappear.

I see this project as part of the great tradition of documentary/fine art photography exemplified in the work of the Bechers, Edward Weston, and Edward Curtis. Their work points to the importance of place, a theme that runs through all my work. To quote Eudora Welty,

“Place is my source of knowledge. It tells me important things.”

My passion for place developed from my training in the social sciences, especially anthropology and history. Moreover, there are few iconic structures more fundamental to the culture and history of the Southwest than its adobe churches. “. . .adobe symbolized the irrefutable progression of life – born from the earth mother, sustained by her during life, and returning to her at death.”( Arrell Morgan Gibson, The Santa Fe and Taos Colonies, Age of the Muses, 1900-1942, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Publishing Division of the University, 1983, page 89) In addition, because Adobe needs constant care, its use speaks to the steadfastness of faith and culture to endure despite the relentless erosion of time and environment.

It is my hope that despite the rapid modernization that took place in New Mexico in the 20th Century, its churches, so pivotal to its traditions, continue to be preserved by traditional means.

Three churches, in particular, exemplify what drew me to this project.

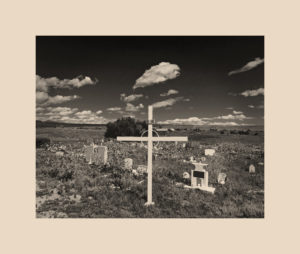

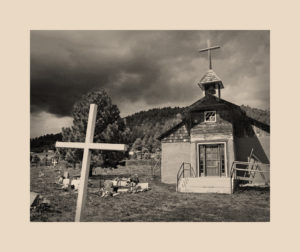

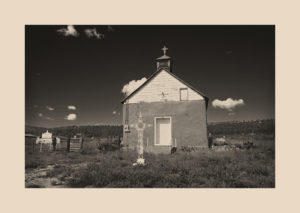

First is the old church in Santa Rosa. Today, the old chapel is in ruins. If truth were told, the community simply outgrew this tiny old structure, and, today its spiritual needs are attended to by a beautiful new church.

While the old chapel continues to serve as the centerpiece for the local Catholic cemetery, and, in its current state, lends a certain otherworldliness to the old graveyard, I cannot help but think how sad that tired old sanctuary must be when it thinks on its past glory.

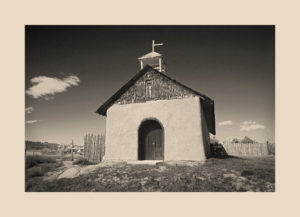

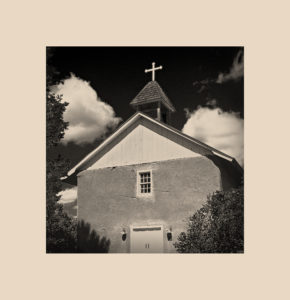

Second is the San Jose Mission Church in Upper Rociada. It was in such poor condition that the building was about to be condemned when a group of local residents, led by Antonio Martinez, came together to save it. While this is a good thing, the youngest member of the workforce was 70 years old when they began their labors. The work was recently completed, and it took ten years to do it. Sadly, I ask myself, will there be anyone left when the ime comes to replenish the traditional mud and straw exterior?

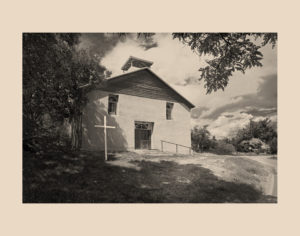

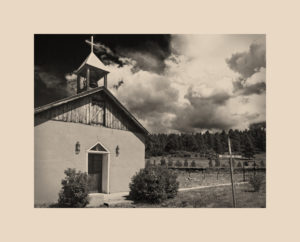

Third is the San Rafael Church in La Cueva. When Joe Gurule’s and Gina Pacheco’s father returned from World War II, he gave thanks by taking a sacred vow to maintain the old church. Today, only his son, Joe, his daughter, Gina, and her husband, Raymond, remain to carry on.

It is a tremendous responsibility, especially considering that, over the years, layers and layers of mud and straw have stressed the exterior walls. Next year they must remove it all down to the adobe bricks and start all over again.

My photographs are dedicated to the volunteers who contribute their time and resources to maintain their community church in the traditional manner. Their unselfish efforts are truly an inspiration.

Pursuing a long-term project opens many doors.

When out in the field, I always have a portfolio at the ready to share with anyone who expresses an interest. If nothing else, this leads to interesting conversations. But, more often than not, it leads to information about churches and people to contact, as well as to many new friendships.

However, project photography comes at a price. It takes a commitment to your creative vision. We are all the sum total of our experiences. We all see, think, feel, and respond differently. Are you willing to share these qualities and expose them in your work? For me, this is what project photography is all about.

The best advice I can give to other photographers who would like to pursue their own personal projects comes from an article written by Brooks Jensen, the editor of LensWork magazine. What follows is a brief summary.

Working on a project is not, necessarily, a weekend excursion. Nor is it an endless pursuit of one’s greatest hits. Instead, it becomes a way of life. For me, photographing New Mexico’s adobe churches has become an important part of my life. Each time I visit New Mexico it is a new experience — light changes, weather comes and goes, and seasons vary. Finding a new church is akin to watching a print come to life in a tray of developer. It never ceases to amaze me.

Please do not misinterpret. A project need not last ten years. It actually could be completed in a weekend or even in an afternoon. On the other hand, because I can only travel to New Mexico every few years, even ten years isn’t enough. There are more churches to find and photograph, and I look forward to future visits to New Mexico.

As for some practical advice, get organized before you attempt a project:

- clarify your goals,

- take stock of your equipment,

- evaluate your strengths and weaknesses as a photographer, and as a person, and

- fit your subject to your style.

Sometimes you pick a project and, sometimes, a project picks you. Nevertheless, as the British fashion photographer, Tim Walker, counsels, “Only photograph what you love.”

When I look back, I have to say that time was my greatest challenge. I was on a strict schedule. In two weeks, I covered over 1,700 miles. I would have loved to stop along the way, for example, at local lunch hangouts — meet people, tell them about my project, and get their feedback. Perhaps, next time there will be time for this.

Also, I must confess that the six months that went into planning my trip was a tremendous undertaking. I was on a mission to find as many traditional adobe churches as possible before actually setting foot in New Mexico. While I already knew of a good many churches, I did not want to limit myself to these.

As you might imagine, living in the suburbs of Philadelphia made it impossible for me to do on site research. Fortunately, I was able to develop a network of contacts that proved to be invaluable. And, I must say that, thanks to the generosity of many individuals, I was able to find 16 new churches. In total, I photographed 38 churches in two weeks.

Bernadette Lucero at the Archdiocese of Santa Fe worked tirelessly to arrange the multiple permissions needed to photograph the churches under its jurisdiction, as did Deacon Randy Copland and Sister Ellen from the Diocese of Gallup. David Blackman and Frank Romero reached out on my behalf to the Christian Brothers so that I could photograph the San Miguel Mission in Santa Fe. Nicole Kliebert from the Cornerstones Community Partnership shared their priceless list of churches from past projects. Larie Mora, whose family owns and maintains the private San Antonio Chapel at the La Cieneguilla Pueblo Site generously volunteered to search out churches for me. Nona Browne and Anita Oderman from the Menual Library in Albuquerque aided with my search for Presbyterian churches. Derek Le Febre and his cousin, Ida Liebert, recommended several churches to be found in the many Mora Valley communities.

Then, of course, at times kismet was on my side. The Estancia Valley Parish told me of their satellite churches, of which I previously knew nothing. And, a chance call to Brenda Murray at the Mountain View Telegraph in Moriarity lead me to Ana Beall, a wonderful watercolorist who has painted many of the churches that I wanted to photograph.

I hope I haven’t forgotten anyone. There were phone calls and emails too numerous to count to parish churches, pueblos and individuals only to sometimes find out that photography was not allowed, especially in the pueblos, or that the churches I was hunting down had been covered with stucco.

For me, perhaps the most satisfying experiences were those I shared with other people. Whether it was a phone call, an exchange of emails, or a passerby who stopped to inquirer about why I was photographing a church, almost to a person, everyone took a genuine interest and was very happy to suggest a church or someone who might help.

Over the ten years that I’ve been working on this project, I have always used the same equipment – a tripod, either a Canon F1 or T90 camera, and a Pentax 6×7 camera. In addition, on this trip, I backed everything up with a Canon G16 camera – just in case something happened with either the shipping or processing of my film.

Unfortunately, these days, working with film is another challenge.

Simply put, traveling with film is no longer user friendly. The good people at Camera & Darkroom in Albuquerque came to my rescue. I was able to order film from them prior to my trip and pick it up when I arrived. I thought that I had ordered enough, but, in Taos, I actually ran out of 35mm film. Unbelievably, the local Walmart was the only place where I could find any kind of film. I purchased a few rolls to tide me over until I could get to Santa Fe.

Because I did not have the time to process my film while in New Mexico, I was faced with another challenge — shipping exposed film back home. Here’s a tip. I found out that FedEx ships film without x-raying it, but you have to ask.

In the past, when working in the darkroom, I would tea stain silver prints. I chose staining over toning because I wanted to color not only the image, but the borders of the paper, as well. The colored borders represent the earth, the source of the adobe mud. Now, while I still use film to capture my images, I scan my negatives and replicate the tea staining process with my own techniques in Photoshop.

Previously, I only used black-and-white film. Recently, however, I switched to Kodak Ectar 100 for all of my photography. My reason for switching to color film, even when my finished product is a black-and-white print, is that, when using Photoshop to convert color to black-and-white, there are so many more options for creativity. In addition, I found Ectar’s rich colors and fine grain to be perfect for landscape projects. Moreover, it turned out to be a great film for scanning.

Was I able to do everything I hoped? Well, the answer to this is yes and no.

As stated in my original proposal, the goal for my Adobe Church Project is to contribute a body of work that: 1) inspires the preservation and renovation of adobe churches throughout New Mexico; 2) demonstrates how important New Mexico’s adobe churches are to its culture, traditions and history; and 3) spread the word beyond the region of the contribution adobe churches make to the culture of the Southwest.

I realized then and now, that these goals go way beyond the financial support provided by The Luminous Endowment. However, winning the award made possible an extended stay in New Mexico. Without this, I would never have been able to make such a significant addition to the number of photographs in this ongoing project.

It is my hope that the prestige that comes with achieving The Luminous Landscape Grant will lead to networking opportunities needed to attract potential funders, museums, publishers and universities to accomplish my additional goals.

My plan is to present my Adobe Church Project to audiences in three ways. The first step would be to mount a major exhibition. I hope that this would generate a greater recognition of the importance of this work, and stimulate a renewed interest in preserving these churches with traditional materials. Second, with the backing of the exhibit hosting organization, I would like the exhibit to travel to the many small towns, villages and pueblos throughout the state – both those that maintain the traditional ways and those that have forsaken them. Perhaps, seeing the beauty and spirituality of their churches covered with the traditional mud and straw, as I do, residents would not be so quick to abandon the customs and rituals that go along with preserving the old ways.

I now feel confident that I have a significant body of work worthy of consideration from publishers and other institutions. I will be reaching out in this direction in the coming months.