What if everything you learned about photography was holding you back?

We master exposure triangles, memorize composition rules, nail focus and sharpness – and somewhere along the way, the magic fades. Our images become technically proficient but emotionally flat.

Pen Densham knows this feeling intimately. The Oscar-nominated filmmaker behind Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and The Outer Limits spent decades mastering the craft of visual storytelling. He was around cameras since age four, when he rode a seven-foot alligator in one of his parents’ theatrical short films. His father, a cameraman, seemed like “the all-powerful wizard with the magic machine.” Densham wanted to cast those same spells.

But he was not happy with his own still photography. For years, it left him cold.

“I was disappointed by my results,” he admits. “I slowly let my cameras languish.” The images he made when he followed traditional approaches felt stiff and rigid. So he focused on film, where he could orchestrate the fluid worlds of light, sound, and motion.

Then his teenage daughter picked up one of his old Nikons.

The Lesson That Changed Everything

His daughter wasn’t following rules. She wasn’t worried about getting it right. Her images were untrained, poetic, and focused in strange ways on odd subjects. They seemed alive in a way Densham’s careful work wasn’t.

“Her naïve, innocent image-making was so much more fluid and ethereal than mine,” he recalls. “Watching her reminded me of something I’d forgotten – that art begins in freedom, not control.”

That observation sparked a seventeen-year journey into what Densham calls “letting go.”

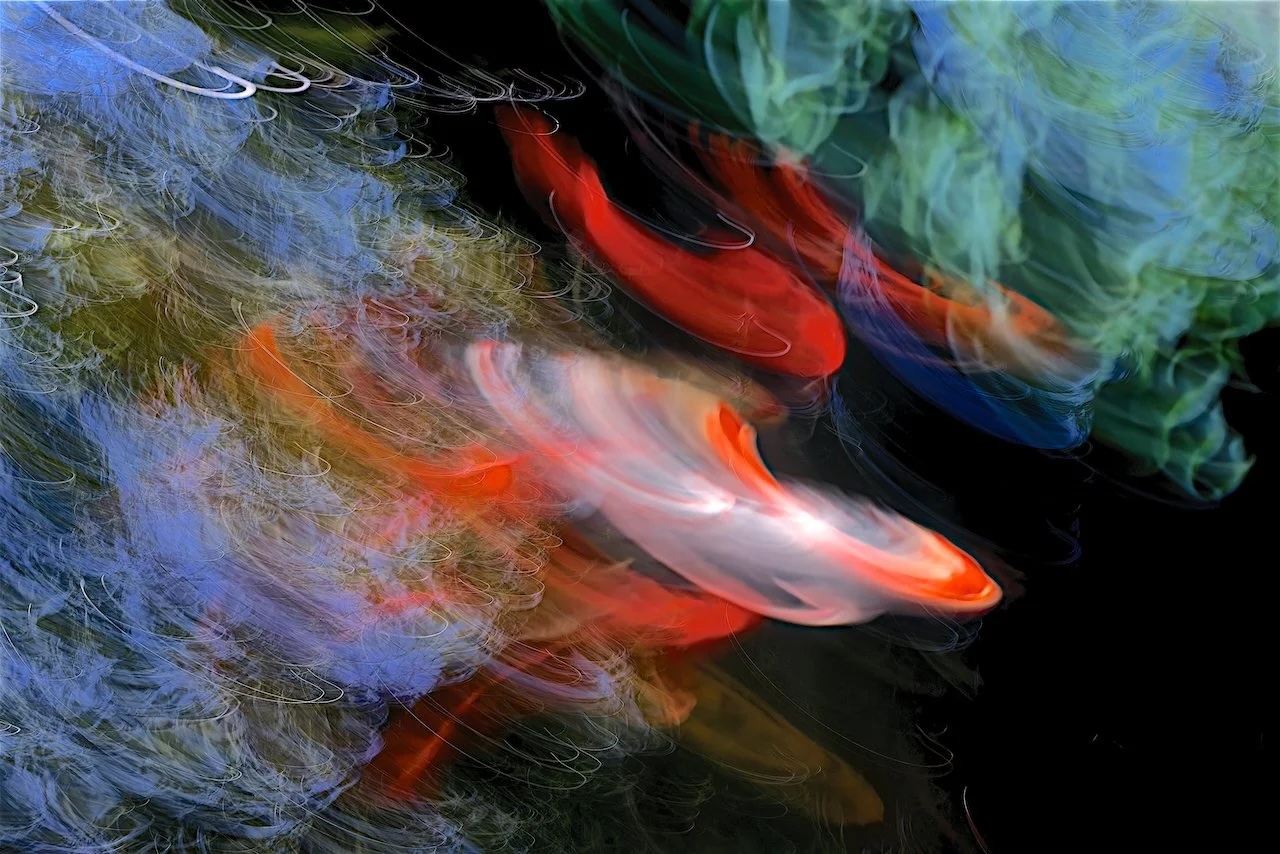

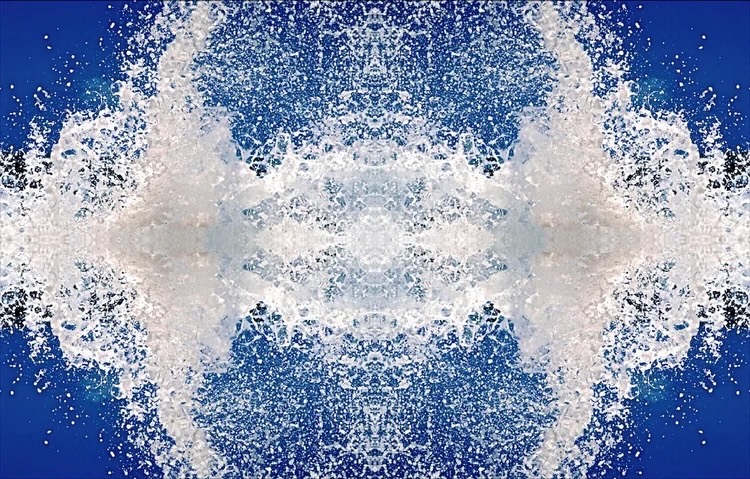

Not abandoning craft, but releasing the self-criticism that strangled his creative instincts. The result is a body of impressionist nature photography that vibrates with the world around him – images of waves, koi ponds, autumn forests, and what he calls “Organic Mandalas” that feel almost like music.

“I fight for my pictures to be uplifting, to be joyful, to be full of energy and vibrant,” he says. “I’m trying to make a movie in a single photo.”

Why Our Brains Need This Kind of Disruption

Here’s where I think it gets interesting – the science behind why images move us.

Densham studied with Marshall McLuhan – the legendary media theorist who coined “the medium is the message.”

McLuhan pushed him to think about the biology of storytelling: why audiences in movie theaters fall into trance states, sometimes moving their lips in sync with characters on screen.

“We’re setting up our mirror neurons,” Densham explains, “watching the characters performing, evaluating their strategies and putting them back into our own heads as possible options for our own lives.”

This biological perspective shapes his photography. When you shoot a tree the “right” way – sharp, still, properly exposed – the viewer’s brain gestalts it instantly. Oh, that’s a tree. Recognition complete. Move on.

But when you move the camera during a long exposure, something different happens. The familiar becomes strange. The brain can’t immediately categorize what it’s seeing, so it keeps looking, keeps processing, keeps feeling.

“This disruption of perspective bypasses expectations and puts the viewer in some kind of personal Rorschach test with the image,” Densham says.

A neuro-linguist who studied his work put it more directly: “Pen Densham’s work bi-passes the logic centers and goes straight to the emotions. Because they are mysterious, yet feel familiar.”

Joseph Campbell’s influence runs through this thinking too – the idea that we’re biologically wired for certain kinds of visual and narrative experiences, patterns that have helped humans survive and thrive for thousands of generations.

Densham’s impressionist work taps into something primal: the shimmer of light on water, the dance of wind through leaves, the rhythmic pulse of ocean waves – a felt experience.

The Techniques: How He Actually Makes These Images

So how does a filmmaker approach still photography? Probably like someone who’s spent a lifetime thinking about motion, emotion, and time.

Intentional Camera Movement

Densham’s core technique is pretty simple: move the camera during exposure. But the key isn’t the movement itself – it’s asking “what does my body want to do?” rather than “what should I do?”

“I might shoot one-second exposures moving with the waves,” he describes. “The sun has already gone down and you just get these beautiful forms.”

For his tree images, he moves his hands during exposures to evoke plants vibrantly dancing.

For street scenes in India, he shakes the camera deliberately, creating multiple synchronized impressions of the same figure – “and as you look at it, your brain is now processing parallel concentrations of what these things are and what they mean to you.”

Try it yourself: Find a subject with strong vertical lines – a grove of trees, tall grasses, architectural columns. Set your camera to shutter priority around 1/4 to 1 second. As you press the shutter, move the camera smoothly in the direction of those lines. Don’t worry about getting it “right.” Shoot dozens of frames.

Shooting Through Light

His koi pond images come from shooting directly through “blinding sunlight” on the water’s surface. The harsh light that sometimes we avoid becomes a collaborator, fragmenting the fish into dancing spirits of color.

“I’m exposing sinuous colored koi through rainbow mists like dancing spirits,” he writes in his artist statement.

Try it yourself: Find moving water with strong reflections – a pond, fountain, or stream at midday. Shoot through the glare, not around it. Let the highlights blow out. Watch how the subject fragments and reassembles into something unexpected.

Long Exposures at Dusk

Densham’s “Wavelife” series began when he waded chest-high into Hawaiian waves with a Lumix LX2. The small camera with its wide rear screen freed him from the viewfinder, letting him respond physically to the water’s rhythm.

“Making long exposures that discover mystical sculptural flows,” he describes the process.

Try it yourself: Don’t wait for golden hour – work through it and into dusk. As light fades, your exposures naturally lengthen. Move with your subject rather than bracing against it. If you’re shooting waves, let your body sway. If you’re shooting wind in trees, let your arms respond to the gusts.

Organic Mandalas

His kaleidoscopic images come from panoramic stitching software used unconventionally. By feeding images that mirror and fold onto themselves, he creates what he calls “weaving mirrored kaleidoscopic reflections.”

“The results can seem three dimensional and conjure the imagination,” he notes.

Try it yourself: Most panorama software (including free options like Microsoft ICE or Hugin) can create surprising effects when fed images that weren’t meant to stitch traditionally. Try overlapping shots of organic textures – bark, water ripples, foliage. See what the software makes of them. The software’s “mistakes” often become the most interesting images.

The Hardest Part: Letting Go of Self-Criticism

Densham’s approach is all about the inner work.

“The biggest effort was letting go of self-criticism,” he admits. “Thinking this is stupid.”

He describes traveling through India, deliberately shooting only “experiential images” while fellow photographers gave him puzzled looks. “I’m sitting with a group of people all traveling India and I’m shaking my camera and they’re all looking at me thinking what’s this guy doing?”

That “technique” of vulnerability becomes the willingness to look foolish in service of something you can’t yet explain.

Try it yourself: The next time you go out shooting, make a deal with yourself. For the first thirty minutes, you’re not allowed to take any “good” photographs. Shoot ugly. Shoot blurry. Shoot into the light. Move when you should be still. The goal isn’t the images – it’s silencing the internal critic and getting curious.

What Photography Can Be

“Photography can be more than a window,” Densham says. “It can be a mirror for emotion.”

His images have been shown in galleries from Los Angeles to Monaco. Collectors respond to work that’s “mysterious, yet familiar” – images that bypass the analytical mind and speak directly to something older and deeper.

“All my life I have wanted to cast spells with a camera,” he writes. “I never expected by letting go – the images would find me.”

“I surrender when I make an image,” Densham writes in his book Qualia – the philosophical term for sensory experiences that can’t be captured in words.

“It is like stalking a dream. Pursuing an instinct as fragile as a flying ember. Hoping that it might kindle into something luminous and amazing.”

Maybe that’s the lesson here – permission for us to let go and create some magic.

Read this story and all the best stories on The Luminous Landscape

The author has made this story available to Luminous Landscape members only. Upgrade to get instant access to this story and other benefits available only to members.

Why choose us?

Luminous-Landscape is a membership site. Our website contains over 5300 articles on almost every topic, camera, lens and printer you can imagine. Our membership model is simple, just $2 a month ($24.00 USD a year). This $24 gains you access to a wealth of information including all our past and future video tutorials on such topics as Lightroom, Capture One, Printing, file management and dozens of interviews and travel videos.

- New Articles every few days

- All original content found nowhere else on the web

- No Pop Up Google Sense ads – Our advertisers are photo related

- Download/stream video to any device

- NEW videos monthly

- Top well-known photographer contributors

- Posts from industry leaders

- Speciality Photography Workshops

- Mobile device scalable

- Exclusive video interviews

- Special vendor offers for members

- Hands On Product reviews

- FREE – User Forum. One of the most read user forums on the internet

- Access to our community Buy and Sell pages; for members only.