Chris Rainier is a documentary photographer, filmmaker and a National Geographic Society Explorer who is highly respected for his documentation of endangered cultures and traditional languages around the globe. In 2002, he was awarded the Lowell Thomas Award by the Explorers Club for his efforts on cultural preservation, and in 2014 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of London UK – specializing in cultural preservation.

He is the founder and director of The Cultural Sanctuaries Foundation – a global charitable foundation focused on preserving biodiversity and traditional culture.

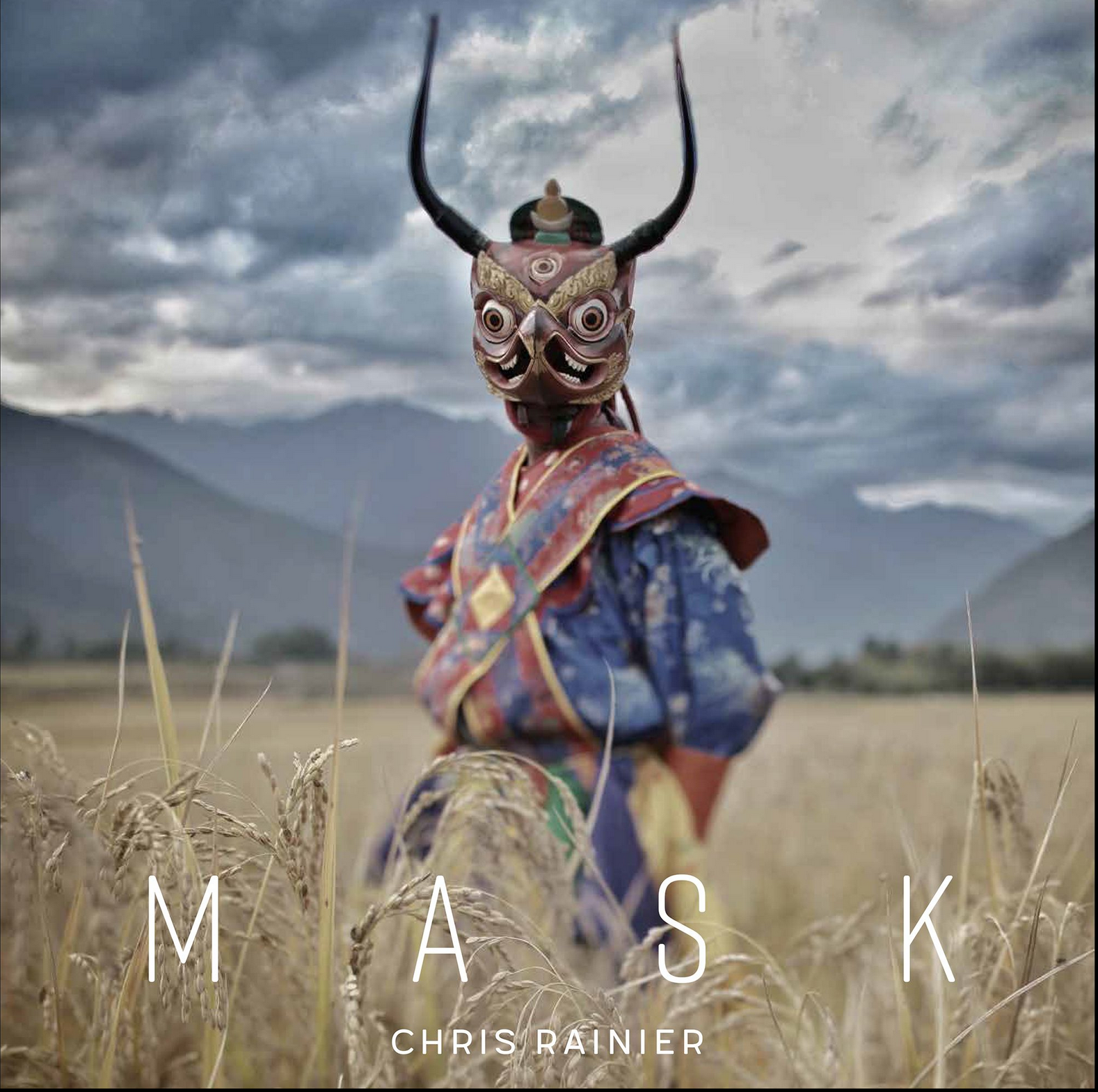

I was sent a link to Chris’s book Mask by the esteemed friend of LULA John Paul Caponigro, who’s own work and voice has been shared here.

Chris Rainier’s imagery coalesces the themes, technicality and vision which I unabashedly and excitedly wish to promote here on LULA. The kind of total immersion of life and photography which opens up worlds to the viewer which need to be seen. This is meaningful work which speaks to the spirit and moves beyond era.

When I was young, my mother would often take me to the Royal Ontario Museum. She worked next door at the Art Gallery Of Ontario. Her workplace was a hermetically sealed, soft carpeted maze of “do not touch” signs and walls of sacred paint. Walls which framed human history and contemporary art in all of the drama, pomp, and splendor one can pay for, but at a very long arm’s length.

The museum next door went even further in this zooification of human and planetary history. It marked off petrified beetles, bones and ancient human artifacts in a strange timeless warp which suggested our history was something detached from our lives. The message being sent was that these totems and objects now sat as mummified relics. Cadavers on display for the paying visitor who inhabited the modern grey world of practical truth and hard-won safety and sanity. It was an occidental and post modern western vantage point which felt foreign to me.

Human magic, eras of the earth’s development, the beasts and beings who cohabited with us were now just dreams which left trinkets to be adored, dusted and never truly made contact with. This sealed off, florescent world, said that we were a new species. We were being Implicitly told that we had advanced beyond our history, somehow detached and flown away to a new world. This message was condescending, deeply blind, and regressive.

None of this detachment felt desirable or true. As a child, I always thought that these masks, armors, bones, weapon, amulets and objects now reinterpreted and beyond modern-minded concept, were trapped in these buildings with us equally trapped away from them. I felt as a result that we were being sequestered into a sterile and condensed reality which eschewed some kind of philosophy that shunned or deeply misunderstood these things.

I knew that they we were more than this, that we were more than this and that non of the power these objects held was truly gone.

Years later, as my life developed, I reclaimed and re-defined spiritual truth for my self. I finally found my own nature to be complete, not just a simulation of post modern tropes and symbols. I found the natural world to be inseparable from me, and I fell in love with it and began healing myself and my previously held perceptions. I discovered that we are not separate from our deep history, from the planet, from indigenous wisdom, culture, or spirit. The spiritual objects and complex curio produced by endangered people (including ourselves) need only become de-energized if we willed it. The truth is that the living continuum of thought, spirit and ritual is vibrant and made of much more than archaic remnants of past templates which our museum culture inculcates, however noble the intention.

At the Tibetan Buddhist Temple I attend, sitting in our cabinet, there is a drum called a Damaru. It is used to aid in ritualized meditation, to help cut away the ego and enter a broader spectrum of conscious engagement with mind-states and beings beyond the conventional. To most people (to most non-Tibetans), the Damaru is simply a decorative cultural artifact from occupied Tibet. It is seen as exotic and rendered to be something born of a superstitious nature. Something we have transcended with the western enlightenment. This is far from the truth. In our tradition we use it often and it is activated in the here and now.

There truly are objects and techniques for deep transcendence. They are only now being re-introduced to our post-modern culture and honored as the sophisticated portals they are, not as mere reflections of a destroyed past, as primitive examples of wrestling with archetypes which psychology has illumined. This view is false. The peoples who have upheld them and nurtured these wisdom traditions are the vibrant living links to our activated histories. They are teachers.

But just as quickly as we are reawakening and linking to own collective natures, we are destroying them.

These are dynamic histories which are still alive and should never be relegated to the walls of a sterile cube, cut off from the bodies and hearts which animate them. Our bodies and our hearts. That violence of neglect or simple fetishization ignites as we genocide peoples, cultures and language, aggressively cut our forests, destroy our water, occupy land for Earth crushing industries built on outlived tech and dishonor treaties, ultimately forgetting what we are.

Chris Rainier, through his photography, does the great work and service of bringing to life and opening a greater window unto these living spiritual traditions which are under the immediate and growing threat of our ignorance and the abyss of our arrogance. He does so through a beautiful lens which honors the living and makes room for the past. Perhaps the kind of work he is doing will help save us. Save us by reminding us not only of where we come from but who and indeed what we are.

His book Mask is a living testament to what we have to lose, what we have to gain and the art of sharing.

I will be conducting a follow up interview with Chris Rainier about his experience making the book MASK, and his other bodies of work as I am sure people will wish to hear his take on the process! More images from this series will be included.

Chris’s site.

Josh Reichmann

September 2019