UnintendedConsequences

There is something calledthe law of unintended consequences. It manifests itself though the occurrence of events that no one could have forecast based on prior developments.

As digital image processing and inkjet printing take hold as the preferred means of processing and printing fine-art photographs, let alone consumer and hobbyist output, one would think that the days of black and white photography would be numbered. Anything but!

Instead what we see is a major resurgence of interest in B&W (monochrome) photography and printing. This has become manifest in several different ways.

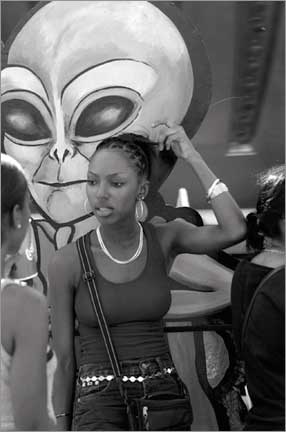

Alien Relations‚ Toronto, 2001

Alien Relations‚ Toronto, 2001

Photographed with Leica M6 and 90mm f/2 Summicron lens on Ilford Delta 100

Magazines

During the past two years there have appeared at least two new magazines that I am aware of devoted to B&W photography, one published in the US and one in the UK. The American magazine is titledBlack & White Magazinewhile the British offering isBlack & White Photography.Black & White Magazinehas more of a fine arts orientation whileBlack & White Photographyhas a more general market approach.

Magazines and their financial viability reflect the real-world state of reader’s interest. If no one buys them, and advertisers can’t be secured, magazines typically have a rapid demise. The fact that in the current glutted state of the photographic magazine market (particularly with so many new digitally oriented magazines), these two specialist journals appear to be surviving, is a sure sign of consumer interest.

In the October 2001 issue ofBlack & White Magazinethe editor points out that they have now been publishing for 3 years and that their readership has reached 23,000. Not quite the 250,000 ofOutdoor Photographeror the 400,000 circulation ofPopular Photographybut quite respectable nevertheless.

Interestingly, in recent issues of both magazines they are struggling with the issue of digital. A large number of B&W fine art photographers have moved to digital image processing and inkjet printing, but there is a fervent group of diehards who want nothing to do with digital, and so the debate rages on.

Chromogenic Films

Photographed with Leica M6 and f/4 Tri-Elmar lens @50mm on Ilford XP2 Super

Though the technology is now a couple of decades old, according to dealers chromogenic films are enjoying a resurgence among photographers. Films likeIlford XP-2 Super,Kodak’s TCN-400andPortra 400 B&Ware designed to be processed in C41 chemistry, the same as all colour negative films. This means that any local mini-lab can process your film in 1 hour at moderate cost. Having wallet-sized prints made is a convenient way of judging results. (Just be aware that all labs are not created equal. Many use poor quality control and can also scratch your film through careless handling. Choose your lab carefully. A mom & pop lab is typically better than a drugstore or chain).

The newPortra 400 B&Wis designed to print with the same filter packs as Kodak’s otherPortra C41films, so the sepia-coloured mini-lab prints of the past are no more. But most decent labs can now printanychromogenic film, including Ilford’s, as neutral black and whites.

I’m particularly fond ofIlford XP-2 Super.While I still enjoydoing black and white film processing, and modern B&W ISO 100 emulsions likeIlford Delta 100andKodak’s TMax 100are unparalleled, XP2 provides excellent dynamic range, fine grain for an ISO 400 film, and real convenience of use. I rate it at an EI of 320 instead of 400 to give slightly denser negatives. This also reduces grain somewhat.

Digital Contact Sheets

Because I closed my traditional wet darkroom several years ago, when I shootXP2I have the lab make wallet-sized prints for evaluation purposes. But, when I shoot real B&W film I’m faced with the issue of making contacts sheets. No darkroom, no enlarger, no contact sheets, right?

Wrong. There’s a simple way of making quick and inexpensive B&W contact sheets in the digital darkroom, and in my article titledDigital Contact SheetsI explain how easy it is.

Printers and Processes

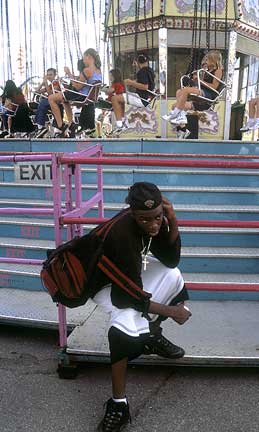

Boys in Chains‚ Toronto, 2001

Boys in Chains‚ Toronto, 2001

Photographed with Leica M6 and f/4 Tri-Elmar lens @50mm on Provia 100F. Converted to Duotone.

Of course shooting in B&W is one thing, but making prints is quite another. How does one make high quality B&W prints without a wet darkroom?

There are several approaches, with more on the way. The simplest is to scan the film as one would any negative. Then, use your inkjet printer. Easy? Well, there are some tricks. I have written two articles, one titledBetter B&W Using Channel Mixerand the other on printing usingDuotonesin Photoshop. Using these two techniques you can make spectacular monochrome prints just with the equipment that you are currently using.

Another approach is to use specialQuadtoneinks. These are available from companies likeMIS. There is also a very highly regarded system calledPiezographyfromCone Editions. This uses alternative monochrome inks and drivers in converted Epson printers to produce very attractive and archival monochrome prints.

![]() I have nowreviewedand started to usePiezographymyself, with excellent results.

I have nowreviewedand started to usePiezographymyself, with excellent results.

There have also been rumours for some months that Epson will be releasing a B&W only printer for the fine art market. No details yet but they’re unlikely to leave this growing niche unfilled for long.

Converting to B&W

In the old days (before 5 years ago)you pretty much had to choose between shooting in colour or B&W. In years past, when I worked as a photojournalist, I would always carry 2 camera bodies, one loaded with B&W and one with colour film. Invariably I’d find that an editor wanted what I’d shot in B&W in colour, and visa-versa.

One of the reason for shooting both back then was that colour film was much slower than B&W. Things are much easier today. The improvements in speed and image quality obtainable from colour film has been quite astounding. But even so, printing a B&W from colour then meant using a type of printing paper calledPanalure, which was panchromatic and therefore responded properly to a colour image. Otherwise tonalities, especially skin tones, would be rendered improperly.

Photographed with a Leica M6 and f/4 Tri-Elmar lens (@ 28mm) on Provia 100F

Today working with scanners and then inPhotoshopit makes hardly any difference whether one shoots colour negative, transparencies, chromogenic or traditional B&W film if the intention is to end up with monochrome prints. Conversions are easy to perform with little effort and a great deal of flexibility is offered. (For the picky and quality conscious worker there are indeed differences, but for most folks this isn’t worth worrying about).

If you have not already done so you should read my article titledBetter B&W Using Channel Mixerfor the best way to accomplish conversions from colour to B&W.

Blame it On Digital

I started off this page by mentioning thelaw of unintended consequencesand how I believed that it has been responsible for the resurgence of interest in B&W photography. Here’s why.

While photography is both a very popular hobby and art form, very few people in the past have had the space, time or inclination to do darkroom work. With the increasing popularity of digital image processing, and especially digital cameras, during the past few years the ability to process images and print them at home has rapidly gone from difficult to easy. This has meant that people who would otherwise never have set foot in a darkroom are now free to explore this aspect of photography.

B&W work has for the past 30 years been largely supplanted by colour. If you didn’t do B&W printing yourself resorting to a pro lab was the only alternative, but at very high prices compared to colour. The desktop digital darkroom has changed all that. Hobbyists as well as fine art photographers are now able to explore the pleasures and rewards of working in B&W as easily as they can in colour. Don’t be left behind. The consequence may be unintended, but they can be wonderful.

The photographs used to illustrate this article are from a photo essay titledMidway.

Read this story and all the best stories on The Luminous Landscape

The author has made this story available to Luminous Landscape members only. Upgrade to get instant access to this story and other benefits available only to members.

Why choose us?

Luminous-Landscape is a membership site. Our website contains over 5300 articles on almost every topic, camera, lens and printer you can imagine. Our membership model is simple, just $2 a month ($24.00 USD a year). This $24 gains you access to a wealth of information including all our past and future video tutorials on such topics as Lightroom, Capture One, Printing, file management and dozens of interviews and travel videos.

- New Articles every few days

- All original content found nowhere else on the web

- No Pop Up Google Sense ads – Our advertisers are photo related

- Download/stream video to any device

- NEW videos monthly

- Top well-known photographer contributors

- Posts from industry leaders

- Speciality Photography Workshops

- Mobile device scalable

- Exclusive video interviews

- Special vendor offers for members

- Hands On Product reviews

- FREE – User Forum. One of the most read user forums on the internet

- Access to our community Buy and Sell pages; for members only.