Jessica Eaton has a problem: people always want to know how she makes her photographs, but few are capable of understanding the explanation.

The Montreal-based artist has been working in the arcane reaches of analog photography for over 14 years. Through obsessive experimentation, she has developed a method entirely her own, combining additive colour theory and what she calls “a really bastardized version of Ansel Adam’s zone system.”

Eaton’s relentless inventiveness and exacting practice have made her one of the most successful Canadian artist-photographers working today. She’s represented by galleries in Montreal, LA, and New York, where she exhibits her work by turns on a bi-annual basis. Viewers and collectors are drawn to the unique tensions in Eaton’s work: the austere minimalism coupled with her daring colors; the hyper-abstraction undercut by a current of playfulness; the defiant impenetrability softened by an aura of warmth.

Eaton’s pictures seem to be taken from another universe, so for most viewers, it comes as a shock to realize they are analog photographs. She operates so far out on the fringes of technical complexity, even serious professional photographers struggle to grasp how she does it, let alone a mere enthusiast like me, slinging a Nikon D700 around in my backpack and half the time shooting on Auto. I hardly stand a chance, but she’s game to try.

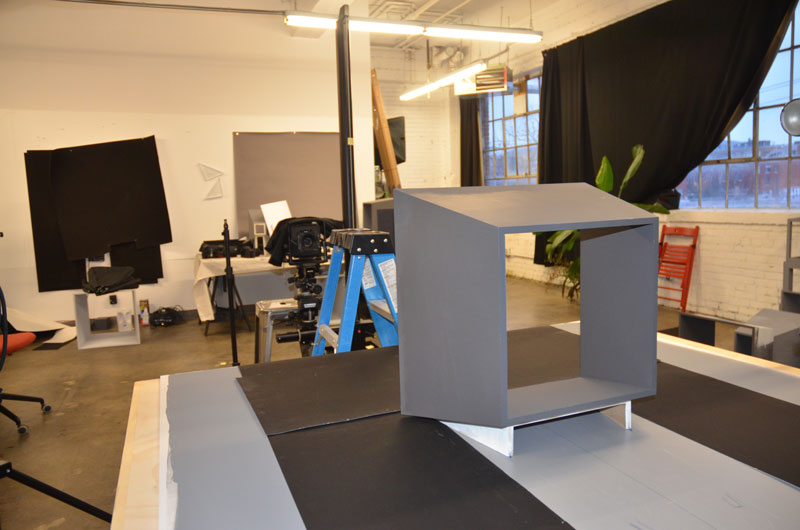

I dropped into her studio just after the new year, where I found her kicked back at her desk with a glass of red wine, taking a break from frenzied preparations for an upcoming show in Los Angeles. The blackout curtains were pulled back from the tall windows in her studio, letting in the last light of the day, which reached almost to the back wall. Everything was organized around a few basic wooden cubes painted in various shades of grey—her sole subject for nearly three years.

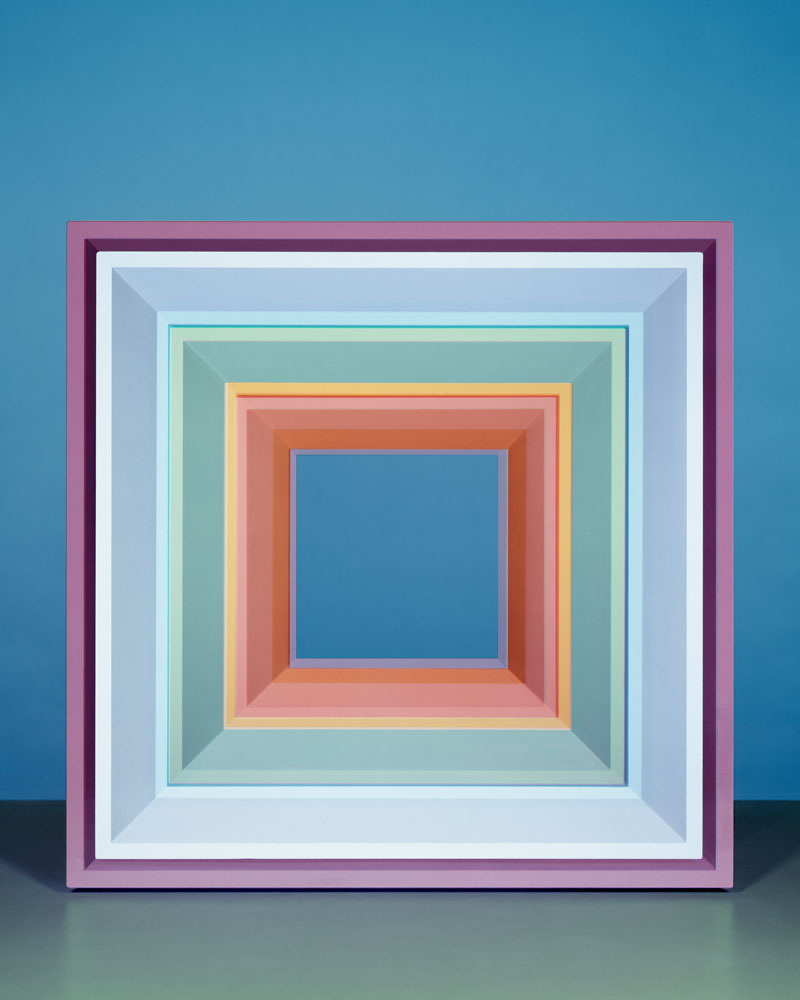

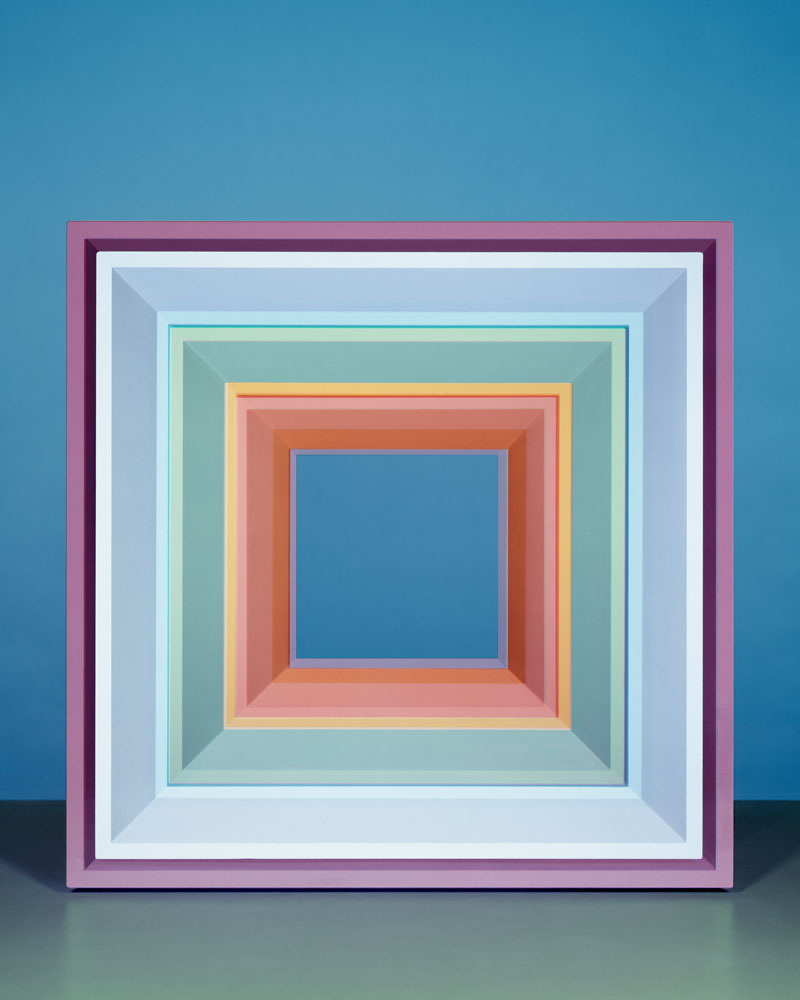

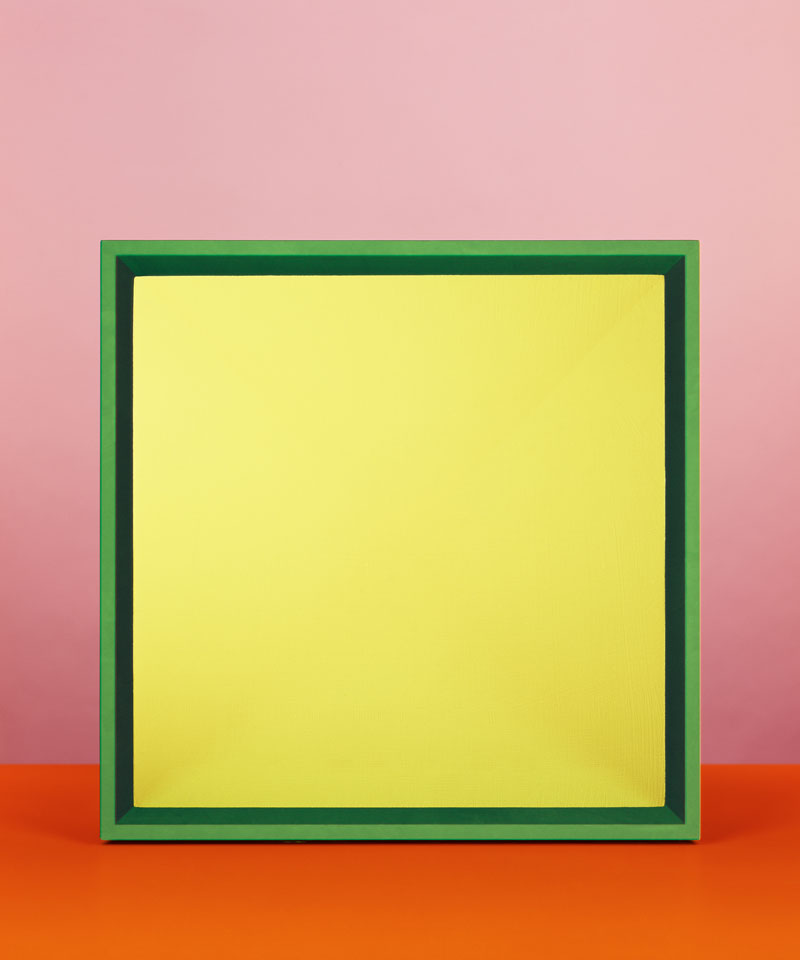

The series, called “Cubes for Albers and Lewitt,” draws inspiration from the great twentieth-century abstract artists Josef Albers and Sol Lewitt. It was Lewitt who said that if you want to make art about an idea, you have to pick the simplest form and repeat it until the form loses meaning and the idea becomes the art. That’s exactly what Eaton has done.

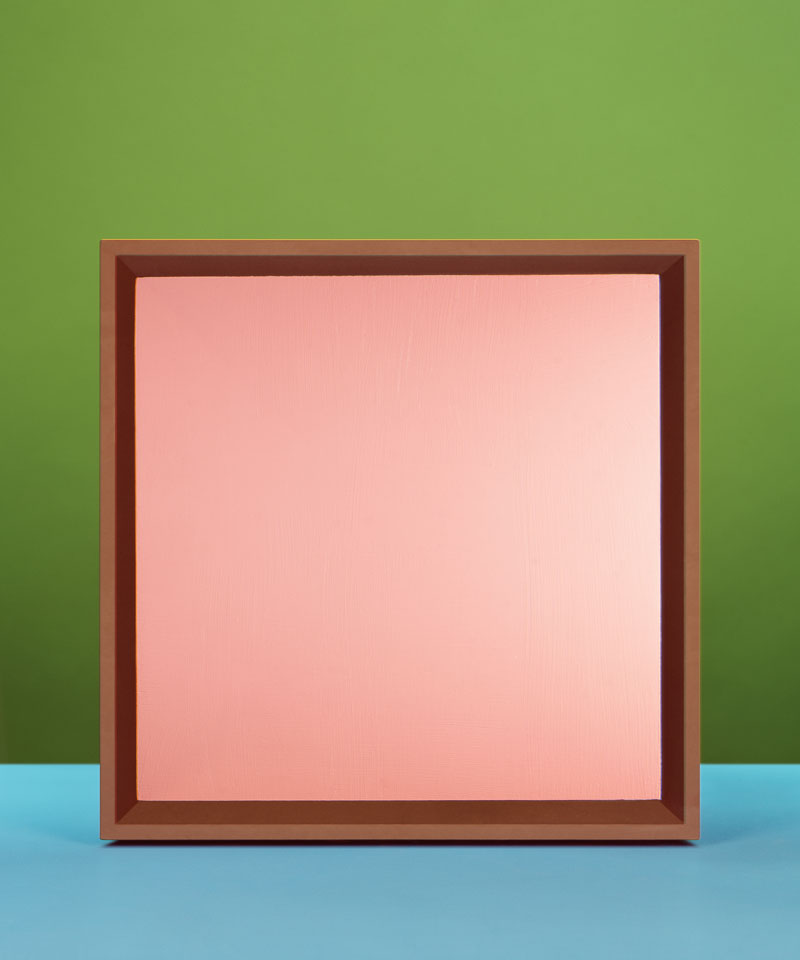

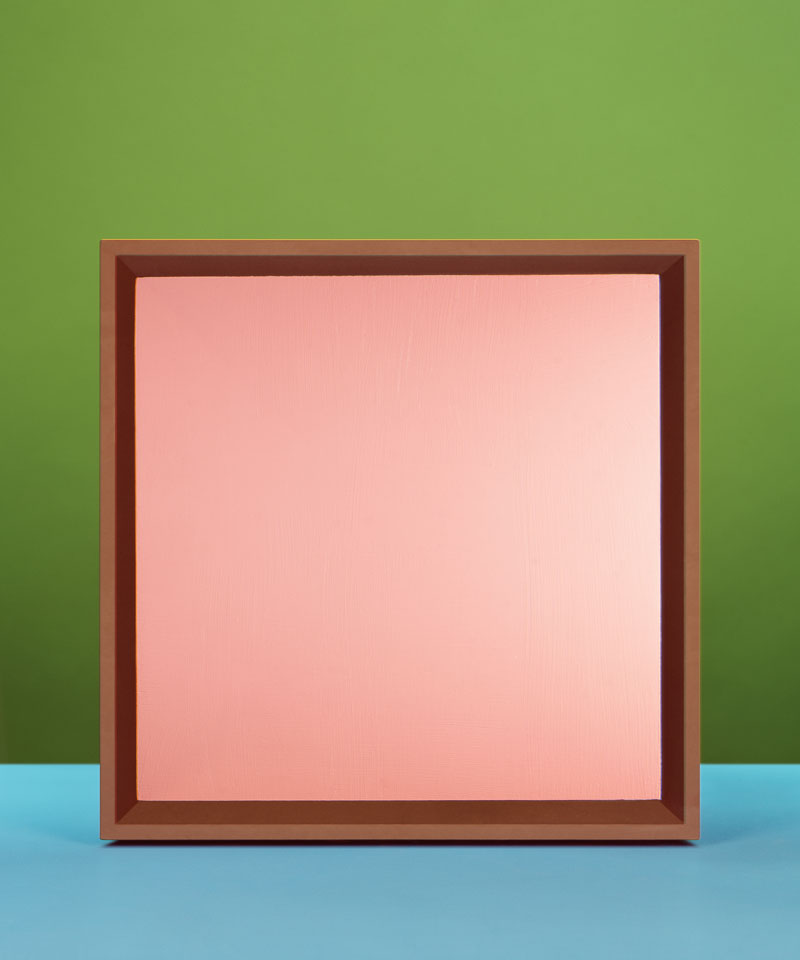

The images show cubes within cubes, set on a simple plane against a flat background. Each cube is a different colour. That’s it.

But after absorbing the simplicity of the work, the viewer is then carried away by waves of subtlety and nuance: the brilliant colors, the pitch-perfect proportions, the alternating sense that the cubes are rising outward or falling away. Looking closer, the viewer discovers brush strokes on the cubes, and realizes that these aren’t digital constructs, but honest-to-god photographs of physical objects. Boxes, to be precise, painted in varying tones of grey. Arranged around her studio, these ashen shapes look like an architect’s mock-up for a future dystopia.

Eaton’s magic consists in transforming those grey cubes into her lively, multi-hued compositions, without the help of digital cameras or software. Which brings us to the unavoidable question: How?

“The pictures I make are completely analog, yet not accessible through our time-space and our visual perceptions,” Eaton explains. Got it?

Conversations with Eaton invariably veer into the realm of the conceptual, because the more mundane photographic catalysts — documenting a moment, capturing a portrait, composing a landscape — don’t inspire her. “I’m not really interested in indexing reality,” she explains. For Eaton, photography doesn’t provide a lens on the world she already knows, but on one she hasn’t yet seen. “I want things that I can’t even describe,” she tells me.

“For most people, photography is taking a recording of a thing you see,” she says. “I’m much more interested in negotiating the camera to see a picture that I didn’t know.”

If all that sounds rather theoretical, Eaton can easily break it down: “I’m into pictures of shit I’ve never seen before.”

To achieve that elusive effect, Eaton works within a set of photographic constraints. By putting limitations and working within them, you can get further than if you just leave things open, she says.

The first constraint is obvious: she shoots on film, a fact that shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that she thinks analog is better than digital. Eaton is often asked to comment on the digital-analog divide, but she refuses to treat the different media as factions in a debate. Neither is superior, they’re just different. You wouldn’t fault an oil painter for not using watercolors, she points out. That being said, she has her reasons for preferring analog, and chief among them is control.

Traditional photography has become very rule-based, she asserts, and now all those rules are automated inside the camera. “Once you get into digital, there’s an extreme amount of decisions being made for you, in terms of the sensor and all kinds of automated functions within the camera that you can no longer override,” she says.

Instead, Eaton prefers “the dumbest box,” equipped simply with an objective, a lens, the projection and a plane. “Everything else becomes a negotiation with actual physical space and reality,” she explains.

The next constraint is more complicated. The ongoing “Cubes for Albers and Lewitt” project, begun in 2011 and pursued intensively for the last three years, serves as a framework for her explorations in additive colour theory. Using this system, she builds up her colours additively, by applying different filters with every exposure, in shades of red, green and blue. The resulting photograph is an assemblage of light, built up in layers. It’s a form of alchemy, except instead of fabricating rare metals, Eaton creates rare colors.

To elicit the colors that she wants, Eaton must make precise calibrations. There are a lot of variables to navigate: the filter factor; the number of stops of light the filter loses; the color of the filter; the reflective value the object; the sensitivity of the film; and the relationships between the respective parts of red, green and blue. “Everything’s in portions of light,” she summarizes.

In order to negotiate with all these elements, Eaton plans each photograph on graph paper ahead of time, using symbols and equations of her own devising. Over fourteen years of working like this, she’s developed her own code, like a private language.

“I’ve made up my own way to use this theory of additive color and how it functions and multiple exposures in the medium, and I’ve combined it all into a systematic process that no one else has ever done before,” she says.

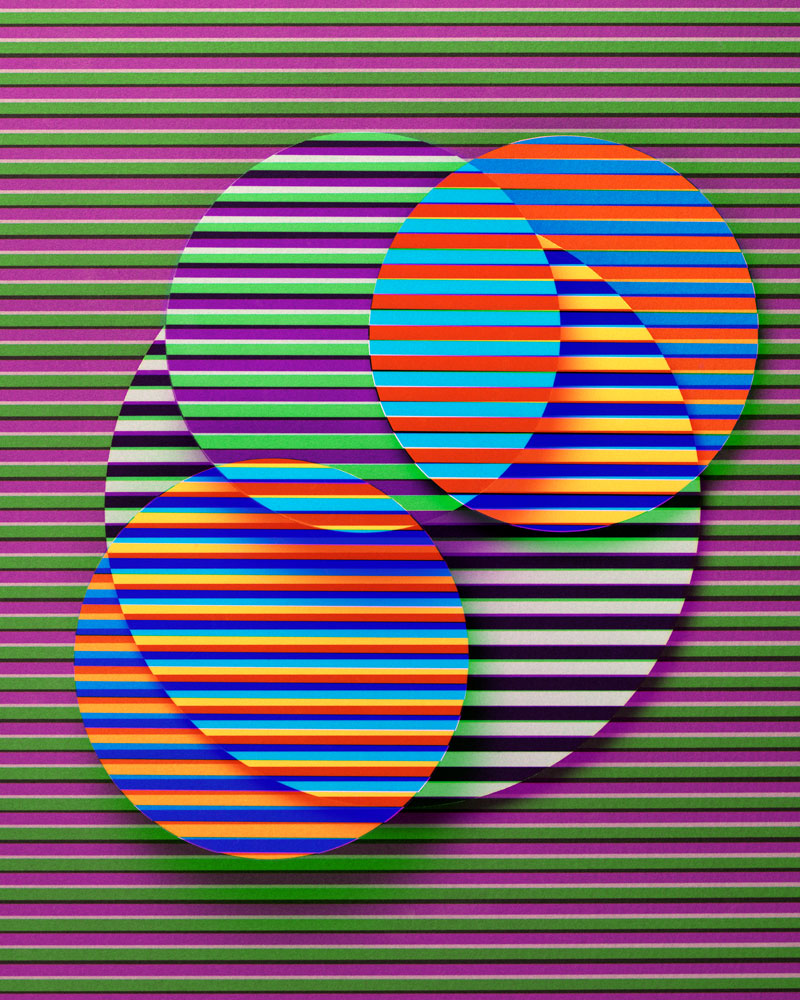

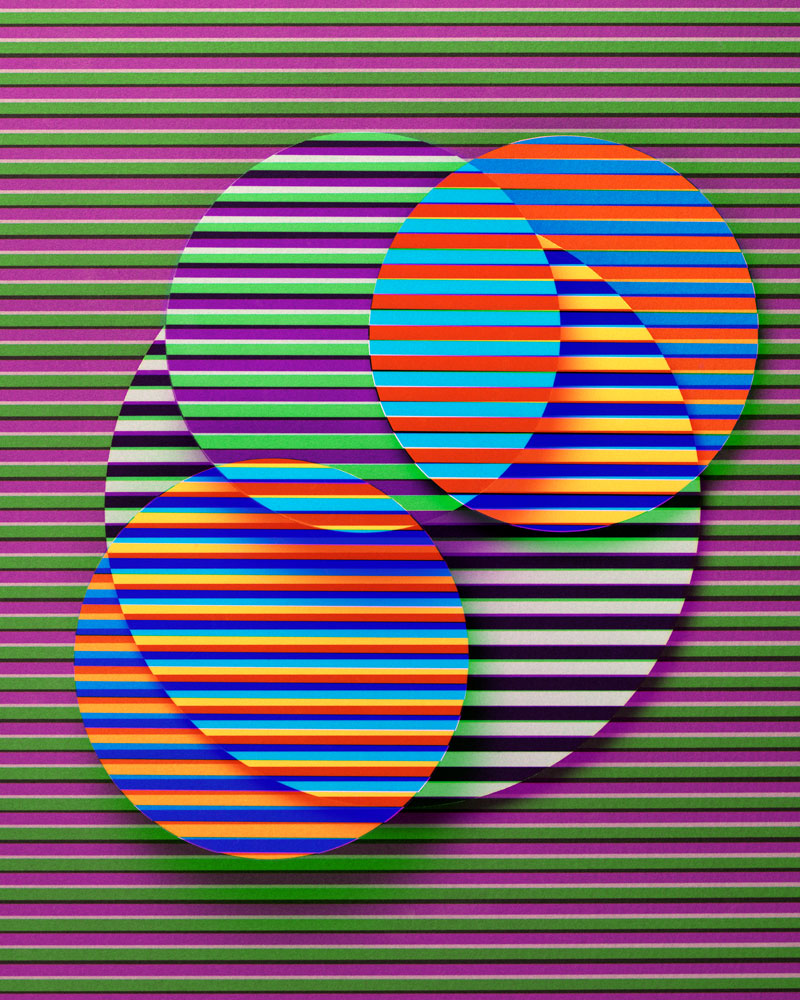

After three years of intensive work refining her technique with the “Cubes for Albers and Lewitt” project, she’s ready to see where else the process can take her. “I’m so sick of shooting these cubes,” she admits, laughing. Now she wants to show off what she can do with her additive method. “I feel like I’ve conceptually bought myself some space from doing such intense work, where I get to shoot a little more open and fun,” she says. “I want joy.”

Eaton’s experimental approach means that she doesn’t know exactly where the next steps will take her, but for starters, she’ll shoot subjects that are more accessible to audiences. “The subject is going to become wild and varied, lots of plants and weird things,” she tells me.

Mainly, Eaton will turn her relentless attention to the print itself. She feels that the digital revolution has blunted people’s awareness of the potential of photographic prints: “No matter what the work is or how brilliant [it is]… the object itself has become the same, because everyone’s making pigment prints.”

Eaton is turning back to the early days of photography, when pioneers like William Henry Fox Talbot experimented with things like mercury and gold to perfect the art of image-capture. “I’m going back to silver gelatin, palladium, platinum printing,” she says. She’ll even experiment with daguerreotypes. “I’m gonna shoot whatever rocks my fancy that is connected to me wanting to see one of these print processes enacted.”

Most excitingly, Eaton plans to make full-color carbon prints, a rare and difficult process that encases pure pigment in gelatin, which acts like a lens, causing the print to shift color depending on the light source. “It’s like a fresco,” she says. “You could put them in direct sunlight for 800 years and they’re not going to fade.”

Color carbon prints need to be viewed in person. “My next show is going to need to be seen in real life, because there’s no way these will transcend online, and the idea is to stun people — because everyone has become so used to just seeing pictures on Instagram — to what a fucking photograph actually can be.”

Color carbon printing isn’t easy to get into. It costs USD$4,000 and takes three months to make a print. Tod Gangler in Seattle (www.artandsoulphoto.net) is only person in the world who makes them full-color commercially.

But however the prints are made, Eaton’s process will continue to be rigorous and multi-layered, and marked by compulsion. “Every time something starts to work, there’s a brief moment of satisfaction, and then you need to see it more, so you keep going.”