So You Say You Want To Turn Pro?

We amateurs who shoot for ourselves have it easy. We can do "professional" work if we want to. In fact, 75% of the photographers who call themselves "pros" really aren’t — they’re just people who get paid for their work every now and then. That doesn’t make them pros. A pro, by my definition, is somebody who works full time at photography and makes 80% of his living selling his pictures. We amateurs can also work for ourselves, find our own subjects, follow our own interests. And of course we can shoot anything at all. Portraits, snapshots, architecture, still life, landscapes, whatever.

Amateurs can shoot anything they want to, including the occasional still life. A pro probably wouldn’t make this shot unless he were being paid by the Peach and Lemon Grower’s Association. (Sony F-707)

Every now and then, I hear some amateur musing about how he’s contemplating a "career change" to professional photography. I’ve got to admit, it makes my blood run cold. Few professions are more mysterious to amateurs. First of all, the work is about 70% marketing. If you’re not good at marketing, or you don’t enjoy it, or you aren’t willing to do it, you’re not going to get very far.

It’s also about positioning. I remember one pathetic letter I got from a photo student when I was working at the magazine. In it, he said that he was in his fourth year of photography school, and he intended to make his living as a nature photographer when he graduated. He said he hadn’t done much nature photography yet, because he hadn’t been able to afford to travel, but that I could use the pictures he did have. He sent along six transparencies, all humdrum snaps of the same nondescript mountain. Along with it, he had included an eight-page contract, specifying every parameter of usage and payment you can imagine.

The first thing that "positioning" means is that you’ve got to make sure there’s a market for what you want to do. Nature photography is so competitive and cutthroat that only a few remarkable photographers who also happen to be remarkable businesspeople can prosper in it. That kid who wrote to me didn’t stand a snowflake’s chance in a roaring furnace. There are plenty of people out there with thousands and thousands of excellent stock nature photographs who aren’t yet making a living at it.

I’ve done an awful lot of portraits over the years, sometimes for pay, sometimes not. That doesn’t make me a professional.

The other thing that "positioning" means is specialization. Many professionals fail because they refuse to pigeonhole themselves. They believe (usually with justification) that they are widely competent and can do all kinds of work — an interior this week, a portrait next week, catalog shots of industrial widgets the next. Unfortunately, that’s not how buyers think. Buyers of industrial widget shots want the best industrial widget shooter, and they wouldn’t dream of hiring a portraitist to do them. I once knew a guy who shot a lot of metal parts for one of his clients who was surprised when his client found another photographer for a particular job. When questioned, his buyer told him, "But you dofoundry parts. That job was forautomotive parts!" It’s that bad.

It’s About CYA

CYA ("cover your ass") is closer to how professional photo buyers typically think. You’ve got to remember, clients want to hire the best person for the specific job they’ve got. Very often, the person hiring and paying the photographer is someone who is accountable to several layers of hierarchy above him. An art director may have to answer to his account manager at the agency, who has to answer to the advertising director at the client company, who has to answer to the VP of sales. So the art director can’t take a flier and say, in effect, "This kid mainly shoots rock bands and nudes of people with piercings. So what? He can probably do a good enough promo shot of the client’s couches." Because then, if the VP of sales ends up hating the campaign and demands to know what idiot hired a photographer who can’t take a competent picture of a couch, the director of marketing will blame the ad agency, the ad agency will blame the account manager, the account manager will blame the A.D., and the A.D. can’t then turn around and cover his ass by protesting that he hired the best possible couch photographer, a guy whose couch photos are widely admired and who has shot successful campaigns for other couch manufacturers — which is what he will need to be able to do under the circumstances. "I just dug the guy’s concert shots of John Zorn and I wanted to hang out with him for a while" will not usually be an adequate explanation for the boss.

On a few occasions, I’ve been privy to the process professional photographers go through when they’ve tried to revamp their careers. In two of the three cases, other people (well, okay, including me) had to sit them down and convince them that most of their best work was in one particular circumscribed area, and that they should specialize and promote themselves only in that area. Their objection is that they can do "lots of things" and that they don’t want to "limit themselves." But guess what? When they finally accepted the fact that they should specialize, their billings went up. In one woman’s case, they went up dramatically.

"Professionals" who do "all sorts of things" are usually bottom-feeders — they’ll take any job that comes along, try their best to do it, succeed part of the time, fail part of the time — and usually either struggle to make the bills or else work another job part-time to make ends meet. It’s the pro who specializes and positions him- or herself for one particular market or clientele who is often the most successful. Even if theycando lots of different things, it’s not often very wise to try to advertise that fact.

The Dry Cleaning Business

The other question I usually ask of people who want to earn a living at photography is whether they think they have the energy and acumen to make it in any small business. Could they manage their own gas station or run a dry cleaners? If the answer is yes, then they also might be able to make it as professional photographers. It’s a business — an entrepreneurial, high-risk business.

There’s also one great downside to a professional photography practice as a business, which is that after you’ve established it, you really haven’t created anything you can pass along to your children, because the business is limited to your own eye. Clients don’t want to hire your assistant. They don’t want to hire your successor. They want to hireyou. So when you don’t want to (or can’t) work, the business stops making money.

And there’s an even more basic point: how hard can you work? I don’t want to generalize too much, but a photo teacher I know at one of the better schools in the country was complaining about his students recently. "They won’t work," he said bluntly. I’m not saying photo students are lazy, exactly; but let’s just say that some schools are not renowned for being overly demanding of their charges. Professional photography is not a "nice life," however much you might think it would be fun to be the next Galen Rowell. It’s not a way to escape the nine-to-five grind. For almost everyone who is successful, a simple nine-to-five job is a life of leisure by comparison.

Please Take My Advice

My advice for people who dream about turning pro is usually "don’t." And not only that, but stop dreaming about it. It’s a tough, demanding business, with long hours, high pay but low yield, lots and lots of marketing to do, and not a lot of opportunity for indulging your artistic side. If youdowant to turn pro, however, do yourself a favor — stop taking photo courses and start taking business courses. Start doing a lot of hard research. A good place to start is to get an application package for a small business loan from the Small Business Administration. I don’t recommend that you actually take out a loan, mind you, but the steps they walk you through will help you start getting a handle on what you’ll need to know to start your business.

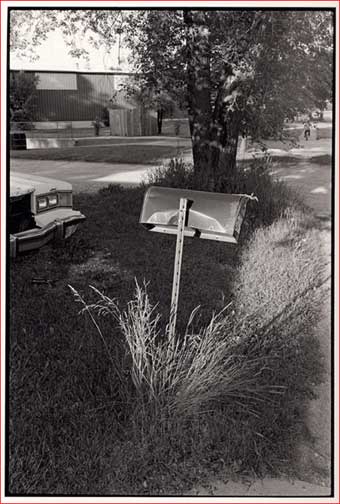

Amateurs can take pictures of any dumb thing they want to, even if you just like the light of the setting sun on an old mailbox. Would you really rather have it any other way?

More than anything, you’ve got to be smart about positioning and marketing. You’ve got to make sure there is a market for the services you want to render; you’ve got to have a workable strategy for appealing to that market; and you’ve got to know how to convince buyers within that market that you’re the best person for those jobs. All that isn’t easy.

Personally, I think it’s a lot more fun being an amateur.

—Mike Johnston

Do you enjoy reading "The Sunday Morning Photographer"? Should you wish to support it,please click this link.

SMP Book of the Week

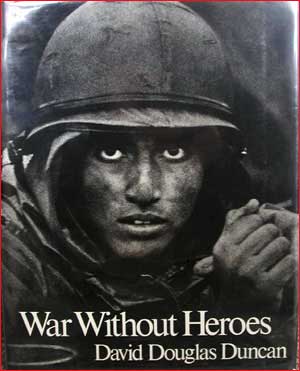

David Douglas Duncan,War Without Heroes, Harper and Row, not dated (1970?), no ISBN. First edition is the only edition.

In 1967 and 1968, photographer David Douglas Duncan, who at the time was held up as a model of what a photographer should be in all the photography magazines of the day, went back to war with the Marines. He had been a Marine himself, and had photographed the fighting in WWII and Korea. InWar Without Heroes— which is at the same time Duncan’s best book, one of the best books of any kind about Viet Nam, and one of the best books of war photography ever done — Duncan did what even the great W. Eugene Smith had tried to assert his right to do but failed at when he had the chance: he sequenced and wrote the entire book himself. And he pulled it off with complete success.

Harper and Row pulled out the stops in producing the ensuing volume, lavishing the finest gravure reproduction quality on it and giving it a thick blue cloth binding. The book was never reprinted. It remains one of the greatest of photographic books.

Here’s what Duncan himself says about it, from the back cover: "This book is simply an effort to show what a man endures when his country decides to go to war, with or without his personal agreement on the righteousness of the cause…in their own eyes, they were participating in everyday events while serving in a foreign land where their country was at war…a war without heroes."

* Current status of book: long out of print, very scarce

* Content: A

* Reproductions: A

* Presentation: A

* Bookcraft: B+

* Synergy and intangibles: ARecommendation: *****

NOTE TO PUBLISHERS: Any publisher may submit any photography title for review at any time.

Please e-mail me:michaeljohnston@ameritech.net

Mike Johnstonwrites and publishes an independent quarterly ink-on-paper magazine calledThe 37th Framefor people who are really "into" photography. His book,The Empirical Photographer, is scheduled to be published in 2003.

You can read more about Mike and findadditional articlesthat he has written for this site, as well as aSunday Morning Index.

You May Also Enjoy...

DxOMark Camera Sensor

This essay is a successor to a previous article [1] published on Luminous Landscape in early 2011. This update explains industry trends using over 50 new camera