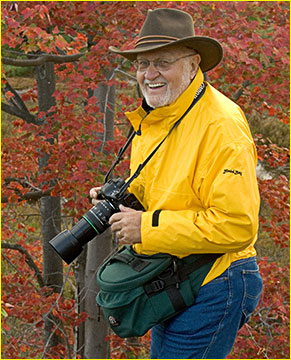

By: Jack Perkins

Rock & Root – Jack Perkins

Returning from aLuminous Landscapefield workshop in Ontario, I found many well-meaning friends asking the same question: “Did you have fun?”

You bet I did. This workshop took us in fall to the vivid Muskoka region of Canada, to Algonquin Provincial Park. The twelve of us, two instructors, ten students, all colleagues, were a companionable cluster of kindred interests and passions, a selfless and giving group. And, yes, we had fun.

But the more I think about it, the more I understand that fun, by itself, is not the measure of a workshop’s worth.

Consider Iceland workshoppers staying up all night to photograph in the protracted summer golden light, then trying to catch some sleep in tents during the daytime. All this while paying three times too much for everything they buy. Is that fun?

Consider Antarctica workshoppers forced to endure perhaps 48 hours of a horrendous, stomach-tossing crossing of Drake’s passage just to get to their destination and then knowing all the time they’re there that they face the same on the way home. Is that fun?

Penguin – Thomas Knoll, Antarctica 2004

No. Those aspects are not fun. But then look at the magnificent image Thomas Knoll (one of our classmates in Muskoka) had captured from a bobbing Zodiac of a penguin atop an icy blue glacier. Didn’t that trump the days of abdominal torture? Plus which, isn’t it true that the greatest experiences in life, the ones that most indelibly imprint themselves in our book of blessed memory, the ones that shape us and lift us and make us better people, often are not “fun.”

For a photographic workshop, there are more relevant measures of worth.

Why does one attend a workshop? To learn. To share. To experience. To be fired and inspired. To be criticized and accept it and grow in one’s art from it. To change.

For years I have most appreciated black-and-white. That’s the medium I’ve chosen for my photography. I justified my choice in an essay in a book of photography and poetry,Acadia: Visions and Verse.

I do not “settle” for black-and-white film. I choose it. Why? Surely color films could have been had by Ansel Adams. Or Edward Weston, Minor White, Alfred Stieglitz. Why, then, are their greatest photographs black and white? [Because} it provides a way of seeing through the distracting camouflage of color to the essence of a thing, a place. It offers a way of simplifying. Which is not to say diminishing. Seeing through to essence is not reduction but expansion; it does not demean, but makes more profound.

Similarly, the photographer sometimes called the Ansel Adams of the Everglades, the great Clyde Butcher, has said, “Color is very distracting. As an art form, I feel that color is a duplication of nature; black and white is an interpretation.”

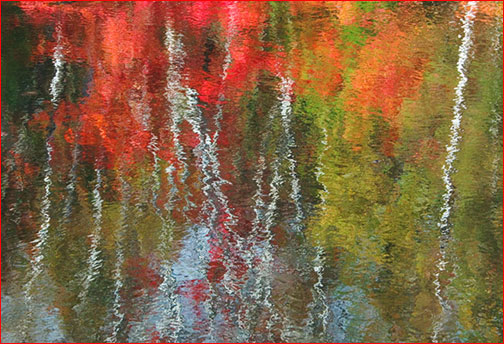

This, I believed as I emplaned to Canada. This, I believe less today. The workshop worked the change. Being confronted with the glorious autumnal palette of Ontario, viewing the magnificent craft of colleagues, the workshop’s encouragement to expand one’s horizons – all these got me to see things differently. So now I sit at my computer working up images of the lush crimsons, oranges, and greens of a Canadian fall as some of my first ever color prints.

Changing and growing. Those are measures of a workshop’s worth.

Muskoka Monet – Jack Perkins

Inspiration is another. However keen we are about our photography, over time the edges dull. We need honed. The workshop sharpens us. How many of us, returned from a workshop, have been up before dawn the next morning to get out and photograph? Or have clamped ourselves eagerly to our computers to open Photoshop’s browser and begin viewing the results of our efforts and working them up? Or have gone back to previous images, ones we heard critiqued at a print review, and worked to better what we had thought were already among our best? Finally, how many of us have snatched up the class list the leader provided and begun what will be lifelong communication with new friends?

And which of us, attending a workshop and seeing the variety of work produced by new friends (how about that fellow who stitched twelve images together to make one picture!) have not picked up valuable tips, learned important lessons?

If, on top of all this making of friends, improving our art, changing our concepts, growing in our craft and being inspired in it, the workshop was also fun, that’s gravy. And – as those crazy Canadians who slather gravy over their French fries will tell you – gravy’s good.

© 2004 – Jack Perkins

_______________________________________________________________

Jack Perkins, by Michael Reichmann

After several decades in television as a correspondent, anchorman, and host (first for NBC News, later A&E’s Biography) Jack Perkins turned to photography and poetry. He blended those in a book, "Acadia: Visions and Verse, which focuses on Acadia National Park in Maine where he and his wife lived for thirteen years.

_______________________________________________________________