By Pete Myers

Hereford Homestead© 2003, Peter H. Myers

Å“The Big House, to which I refer, isliving the dream life, in the big house, up on top of the hill ‚ a metaphor for what we often visualize as theAmerican Dream ‚ not the slang term for‚ prison.

The subject of this article is thecriticismof art — and my feeling that many criticsdelightin moving an artistfrom the big house, to the outhouseby means of their irrelevant comments.

Today, everyone with an email account and a keyboard has the power to become a critic of someone else’s artwork. While the Internet has brought the world together in many ways, it has also produced social phenomena of bullying and irrational actions from anonymous critics.

The Internet has affected artists’ work in a disproportional way, as the medium is considerably visual in content. We can now distribute visual works of art with ease and at low cost. While this development has accelerated interaction in the arts and a sharing of our works and thoughts, it has also made art an easy target for endless criticism — an unnecessary practice, except to the delight of the “critic” dishing it out.

Today’s artists may rightfully fear sharing their works publicly, due to the inevitable blasphemous criticism when their work is exposed.

Art is a metaphor for expressing an artist’sfeelings. As long as an artist is true to his or her feelings and makes an attempt to express them in a genuine fashion, then it is not up to any viewer to judge that artist’s works. If we as viewers do not respond to the content, perhaps we are out of step with what the artist is attempting to express, or perhaps the artist has fallen short in his or her visual metaphor or technique in expressing it. If the latter is true, it is none of our business. It is up to the artist to discover his or her own path to self-expression.

In her book,The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron has a beautiful term for those who go out of their way to squish the emerging artist like a bug. She calls themwet blankets ‚ which is a term derived from the concept ofsmothering a fire with a wet blanket.

I find that there are few critics who do not fall into the “wet blanket” mold. Their own personal frustrations in becoming an artist have made them turn on themselves — and then they go on to smother those around them who are attempting to live their lives as artists.

Needless to say, universities are often chucked full of “Professor Wet Blankets.” I have personally met scores of artists over the years that have reported to me that their creativity was choked out of them during their years in obtaining a bachelor’s or master’s degree of fine arts. Instead of their work being nurtured by their professors, it was systematically picked apart, killing the artist within from a thousand slashes of irrelevant critique.

There are six billion, four hundred million people on Earth, and the numbers are climbing. The jealousies that I see between artists simply astound me in light of the huge audience available for their works. All of us have feelings that are unique to whom we are. Expressing those feelings through our artwork is personal. While one can rip off or “emulate” another’s technique, no one can “borrow” how another person feels inside — and that is the likelyessenceof any masterwork of art.

Every society is formed and functions around a common mythology. The mythology of our society ismoney. We have been taught from a young age that if we do all the right things in our education, affiliations, and work, we will be rewarded for our efforts. And the reward will be inmoney ‚ so that we can buy material goods that will make our lives‚ happy. While all of us have a need for some amount of material goods in order to keep our lives going, often happiness does not go hand-in-hand with the‚ rewards of our mythology. Simply,moneydoes not equate withhappiness.

Further, many of us are also raised on a cultural diet of ablack-and-whiterationale, wherein there is onlyrightandwrong,successorfailure. You’re either in the winner’s circle at the end of the day or are just another loser — and the evaluation is not in how you play the game, but in what is on the final scoreboard.

Ourmoney mythology, accelerated by ablack-and-white rationalerear their ugly heads all the time in criticism within the arts. The value of the art is judged in its literal worth in dollars and cents and its “market value” — not its worth in terms of the feelings it evokes in the viewer. Further, the work is either considered “gifted” or a total failure. Black and white, black and white — and nothing in between.

The function of the artist’s work in society is not part of ourmoney mythology. The artist’s work is to view the world around them with an emotional connection to their subject, and then report their perspective through a visual metaphor within their artwork for their feelings towards the subject. The roll of the artist in society is to reconnect humans by practicing theintuitiveperception offeeling ‚ which is the function of the right brain lobe of the human brain. Great works of art are simply metaphors for conveying a perception of feeling from artist, to viewer. When more than one viewer is able to perceive a sense of feeling through an artist’s work, the artist has created alanguagewithin that work connecting humans throughintuitive perception.

Since the function of a societal mythology is to judge others by the standards of the mythology of the society, many in our society continue to judge art and artists as a commodity —butart is not part of the money mythology. And this is the conflict with so many artists living within our own mythology. While their work as an artist does not fit the mythology of our society, their sense of personalworthhas been established within the mythology. When their own work is not rewarded with money, then artists feel that they are personal failures (because that is the measure of our culture towardsworth). In agony, the “failed” artist becomes a “wet blanket” to others.

Let us slow that phrase down and replay it: In themoney mythology, when the emerging artists do not find their work rewarded with money, they equate the lack of money with failure as an artist. Therefore, with ablack-and-whiterationaleto guide them, they must conclude that they are failures as artists. That is to say, they are not winners or gifted, but are, rather, losers. And with this mythology playing out in their minds, it is the end of their adventure at becoming artists. The little voices of the mythology of our society have ground their nerves away. Their “failure” at becoming artists creates the rocket fuel of the future critics forming within. The most dangerous and deadly critics arefailed artists. Many become thegatekeepersof our most prestigious art institutions and galleries.

So let us take themoney mythologyout of the equation and see its impact on the problem. What if we could wave a magic wand and every artist was able to make a decent living off of the production of his or her artwork? Would that end the creation of “wet blankets”?

Not likely, because many would revert to theblack-and-white rationaleof one winner, the rest losers. Even if all artists were paid a decent amount of money for their works and could work freely, many of them would then push on to competitiveness and vie for attention for their works of art exclusively. They simply would want to be the one and only true artists in a sea of want-to-be’s. In other words, they would destroy or be destroyed!

I would like to make a few suggestions for living a happier life as an artist, without the chains of criticism riding up one’s shorts and ruining one’s life adventure. Here are a few of my ideas:

ONE:The best “criticism” is NO CRITICISM. The best encouragement of fellow artists in understanding their work is when they have done somethingright, not what they have done wrong. Learning is experimental by nature. Our brains just keeps plugging away at all possible outcomes until something rings true to our internal comparator system that we have reached the right result. So much of art is in being able to visualize the “right outcome” before beginning the work. When artists have expressed feeling through their artwork, the recipient — the viewer — will be emotionally touched inside. When that happens, the artists need to know that their artwork “connected.” This ispositive feedbackand results in the artists understanding what connected with their vieweremotionally, based on the actions in their work.

I could hand almost anyone a camera, ask that individual to take few thousand photographs with it, and upon my viewing the results, I would find something that will yield an element of truth or beauty about the person taking the photos. While technique might be lacking in the photography, there is likely to be a basis of feeling in the images expressed by the photographer that will ring true in one or two photos.

As the proficiency of the photographer increases, the shooting ratio between mediocre and good photos narrows. Instead of looking for a needle in a haystack, viewers who feel “connected” with some images will find a feeling of connectedness with images to be more frequent.

Learning is non-linear. Just because this week a photographer is hard pressed to find his or her needle in the haystack does not mean that this situation will be true in the following week. Learning does occur in leaps and bounds — and always through experimentation. Hence, when the critic declares war on an artist, stops that artist’s experimentation in its infancy, and rules the artist’s work as unfit for viewing, the critic kills off all growth and learning — which is the critic’s intent.

TWO:Stop competing against others and yourself. Art is a metaphor for your own personalfeelings. Are you supposed to “out-feel” someone else’s view of the world? I can assure you that people will find the genius of your own work through the feelings you have expressed through it. More artists would benefit from psychotherapy than from art school. Being true to your own feelings and able to express them through what you see is the key to successful art. Again, those who cannot do so become the most pointed critics of those who can.

THREE:Take your art out of the money mythology. Our world is in need of communicating one with another in terms of feelings. Feelings are difficult to express in words, ever worse in translation from one language to another. As the world gets smaller, we have greater and greater need to share with each other what it is to be whom we are inside. That is the roll of art in society. That is what we do as artists.

To illustrate, an “art consultant” recently approached me in regard to my own artwork. She wanted to “re-package” my work to be “more successful in the fine art market with collectors.” In a nutshell, I was supposed to create an illusion that my works of art were scarce, fleeting, and of unlimited escalating monetary value — the dream of “art collectors.” It was amazing to me to find an art consultant without interest in the artwork itself, but rather just in the illusion it would generate as acommodity.

The world is vast and bountiful. If your works of art deliver meaning to their viewers, I can promise you that good things will follow. In what form that will show up in your life is uncertain. Do not make judgments about your own work or those of others through the glasses of ourmoney mythology ‚ It will not work.

FOUR:As you start to find peace in your accomplishments as an artist, go out of your way to foster such feelings in other artists. Surprisingly, many artists will not take to your encouragement — compliments acting like seeds in infertile soil. But there is so much talent that is only in need of simple encouragement. See the beauty once again through their eyes, and not be selfish enough to think that it’s only something you can see yourself. In giving, we receive more then we give—a chance to look anew.

I know of artists who refuse to comment at all upon other artists’ works. While not criticizing, they certainly do not encourage. “Sitting on the fence” is a form of passive censorship. Saying an encouraging word is not false, but should be viewed as a positive response to the level of accomplishment that is before the viewer today. The idea that everyone’s efforts must be viewed on an absolute basis is absurd, and is simply a byproduct of our culture’s obsession for viewing actions with extremes (black-and-white rationale). Those who cannot comment with care and enthusiasm upon another’s works are likely “blocked” in their own path as artists.

FIVE:Get away from critics and criticism at any cost.Whether the critics are friends, family members, or the most learned advisor, criticism is not what you need in your life. You need to celebrate the benevolence of what you’re feeling, seeing,and can express through your art.The only ugly art I ever see is that which has been made as a “product” and not as a “feeling.” Your work, my work, their work — It’s the same work. But none of us has the samefeelingsinside. That is the gold. Get your feelings into your artwork, and get away from those who want to stifle that process by offering their “friendly criticism.”

The Myers Certainty Principle of Photographystates:

The closer your heart is to your subject, and the shorter the exposure, the more certain you will be in capturing its essence in the brief, fleeting moment we call “feeling.”

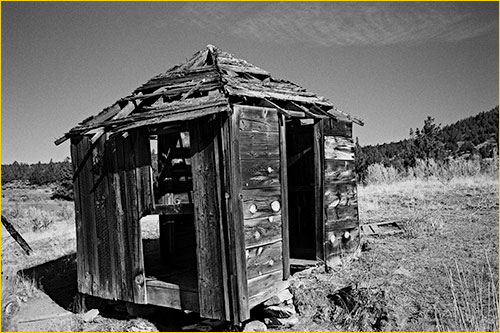

Someone’s Annex © 2000, Peter H. Myers

© 2006, Peter H. Myers

You May Also Enjoy...

An Informal Wide Format Printer Comparison

What is it about photographers? Give them a great new tool and the first thing they want to do is compare it to their last

Winterscapes Of The Alaskan Arctic

It was early March, and another cloudless 70 oF day had arrived in Los Angeles. Trees were leafing out, flowers were sprouting across nearby deserts,