By: Alain Briot

Alain Briot is one of the most successful landscape photographers working in the American Southwest today. His work is widely exhibited and collected. His monthly column for this web site, of which this is part, is calledBriot’s View. An extensive interview with Alain is included in Issue #1 ofThe Luminous Landscape Video Journal.

Lamont and the Grand Canyon

I metGeorge Lamont Mancusoat theGrand Canyon. He liked to use his middle name,Lamont, which was his mother’s name. Phonetically Lamont means “the mountain” in French, something I mentioned to him soon after we met.

George knew and liked this connotation. I perceived him as an alpinist ready to climb the Mont Blanc. He preferred to start hiking downhill into “The Mountain Lying Down“, as theGrand Canyonis poetically called.

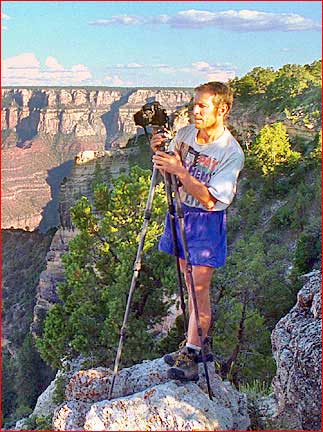

George Mancuso — © Alain Briot

George Mancuso — © Alain Briot

TheGrand Canyon. George’s name was attached to it like to no other place. Originally from New York, of Sicilian ancestors, George was a complex mix. When I talked to him about unfair competition in my business George told me to “Just call me. I’ll come with the violin case.” He was proud of his Mediterranean heritage and, with myself being originally from France, we had something in common besides our love of theGrand Canyonand of photography. George’s favorite musician wasJean Lou Ponty, whose style may be described as romantic jazz rock. When not hiking in theCanyon Georgewould followJean Lou Pontyon his American tours. He also used Ponty’s music on slide shows of his work.

Out of all the possible places it seems like the only place where I could have met him was theGrand Canyon. George to some extent was theGrand Canyonand theGrand Canyonwas George. There was a little of each in the other and their destinies became in some ways intertwined. The problem was that they both existed on different time scales. While 100 years may be as far as we can hope to last, it is hardly enough to make a difference in theGrand Canyon.

The Rainbow

Bright Angel Point Rainbow — ©Alain Briot

Bright Angel Point Rainbow — ©Alain Briot

I met George at theEl Tovarhotel where I show my work throughout the year. At that time, in August 1998, I had a large photograph of a magnificent rainbow arching overBrahmaandZoroastertemples. This photograph was taken a few minutes before sunset fromBright Angel Pointon theNorth Rimand I had it prominently displayed in my exhibit. George came to me — of course I did not know that it was George at that time — and his first words to me were, “I have this photograph. No, I’m serious, I HAVE this photograph.”

Bright Angel Point Rainbow — ©George Mancuso

Bright Angel Point Rainbow — ©George Mancuso

Now you need to understand that during shows we meet all sort of people and that patience, and above all, diplomacy, are valuable skills. So I just smiled and said “That is wonderful,” not knowing exactly what was going on.

Here was this little excited guy, in shorts, with a day pack and hiking shoes, muscular, jumping around my exhibit and on a regular basis returning to theBright Angel Rainbowphotograph for another look.

“This photograph was taken August 12th 1998,” said George. I looked at him, and, unsure of the exact date I actually took the photograph since I rarely keep track of it said, “That could very well be.”

“It was,” said George, “I was there, I have this photograph. I have in the stores as a postcard.”

I’m sure you can see it coming at this point. Only a limited quantity of individuals print notecards and have them for sale inGrand Canyonstores. This had to be real. I asked George who he was. “I amGeorge Mancuso, owner ofGranite Visions. I have this photograph, I just introduced it this year. We were there at the same time but because yours was taken from Bright Angel Point and mine from the lodge we didn’t see each other.”

The Friendship

From this surprising beginning George and I developed not only a friendship but also an affinity. George looked at others in terms of how they related to theGrand Canyon. Of my work he said “You make the Canyon proud.” >From his comment I concluded I had been “vetted” and was part of his circle of accepted photographers. George approved of my work and the canyon approved of it as well. Not that I needed the approval or that I placed George on a pedestal. I didn’t, at least from a photographer’s standpoint. It was simply that I understood George was looking at my work not simply as a marketing venture but as an attempt at portraying theGrand Canyonin a respectful manner.

George believed that theGrand Canyonhad a soul, that it wasn’t merely rocks, strata, and accumulated layers of lava and sediments. There was something there that not only was alive but also animated the parts so they formed a whole. This whole could only be known through its parts and it was perhaps to visit of all those parts — a life-long endeavor to say the least — that George had tackled.

In this endeavor the Canyon both rewarded George and punished him, seemingly randomly, with a logic known only to itself. George in turn came back elated from his inner canyon hikes, disappointed from not having been able to reach his goal, or mangled from a bad fall or other accident. In 1999 George took a bad fall climbing out of the Canyon and trying to reach the North Rim. In an incident which he only vaguely and quickly described he apparently fell while climbing a rock face attempting to find a route towards the North Rim. He injured his knee in the fall and was barely able to make it back to his vehicle after a march that took all he had.

On this fateful day everything seemed to go wrong for him: first he fell and injured himself, then the weather turned bad, it started raining and the temperature dropped close to freezing, and then he forced himself to do a two day hike in a single day for fear his knee might get worse and he wouldn’t be able to come out. Hiking in a daze, George told me that would he have found anyone on his way he would have pushed them over, because he could not afford to stop or be distracted. George’s only goal in life at that specific time was to make it back to his car. He expected no help, knew he could count only on himself, and could not afford self-pity.

This event had lasting consequences on his existence. His knee never completely healed. And although he could walk with the same strength as before it was a constant reminder that something had gone wrong and could not be remedied. He tried surgery to no avail and experimented with various new age products but without lasting results. Interestingly enough his knee hurt most when he was driving and less when he was hiking with a heavy pack. “It likes the weight,” George told me. And so it was that his favorite activity had also become a way to lessen his physical sufferings.

Granite Visions

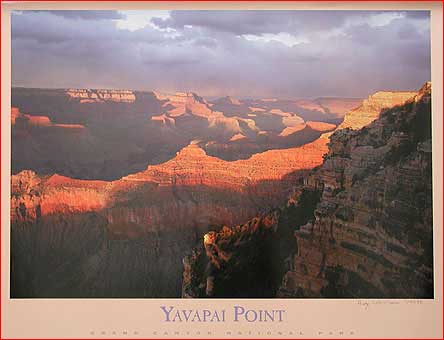

Yavapai Point Poster — © George Mancuso

Yavapai Point Poster — © George Mancuso

In his early exploration of theGrand Canyon Gorgefocused on theGranite Gorge, climbing its sheer walls apparently free-style and blazing new “routes” outside of the gorge. From these endeavors he coined the name of his fledging business: “Granite Visions.” I believe that the word “visions” came from a certain understanding — visions, as in avision questso to speak — of the road which lay ahead of him both in terms of business and of his personal life. These visions came out of the granite (schist actually), the hardest, oldest and most unforgiving rock in theGrand Canyon. This hardness, metaphorically, may have represented his desire to succeed.

From these beginnings his business followed his life and his life followed his business. George would publish posters and postcards, exclusively about theGrand Canyon, of areas that fascinated him and had a good chance of being popular with customers. From the beginning there was a conflict though. While, in George’s own terms 80 per cent of the collection consisted of inner canyon views most of his postcards and posters depicted views from the Canyon’s rim.

It is clear that in terms of marketing, rim views are, and will continue to be, more popular than inner canyon views. There is one good reason for that: the wide majority of visitors see theGrand Canyonfrom one of the rim overlooks while only a small percentage of these visitors ever venture below the rim.

As a photographer I have always considered George’s rim images to be stronger than his inner canyon views. Certainly, there is no rationale for this as the Canyon is just as photogenic inside than at the top, and the opportunities for stunning inner canyon views are just as numerous as those for rim views. In fact it could be argued that there are more possibilities for great inner canyon views than for rim views. Yet, it is my feeling that George seemed to capture the splendor and the essence of theGrand Canyonbetter in his rim views than in his inner canyon views, at least in his published photographs (I haven’t had the chance to see his unpublished work).

But there is one exception to this statement, one blazingly beautiful exception: George’s photograph of “The Confluence” as he called it, the confluence of theLittle Coloradoand theColorado River. In this image, which was George’s all-time best seller, available both as poster and postcard and reprinted several times over the years, George shows a peaceful scene in which the “Blue Waters” (as George loved to call them) of theLittle Colorado Rivermerge with the brown tones of theColorado Riverwhile clouds play with light and shade inside the lowerMarble Canyongorge, creating an amazing sense of space and depth. In the foreground several rafts are tied to the shore and river runners are visible, their stature reduced to that of ants, thereby giving an unforgivable sense of size to an image which George had all the reasons in the world to be proud of.

The confluence, and the “Blue Waters” of theLittle Colorado River, was George’sShangri-La. It was his paradise on earth, his solace, and his haven away from the storms of life. It was a refuge, a home away from home, as much as a destination.

“Seventeen days. Two permits back to back. $100. Not back for a two week vacation!” These were George’s words announcing his trip to theConfluencein June 2001. Leaving his green Dodge Pickup with “Kenobi” license place atLipan Point, parked under a Juniper at the top of the hill, George started hiking around 4 PM to avoid the heat of the day and aimed forGardenas Buttewhere he would set up a dry camp on top of theRedwall. He carried eight quarts of water inside a backpack totaling 80lbs. The weight made it impossible to swing this behemoth directly onto his back so he had to first lift it on his right knee and then hoist it on his shoulders. The weight forced him to walk hunched forward to better distribute this heavy mass over the length of his back. Wishing him good luck at the top of the trail “a nice send off” in George’s own terms, I feared for his apparent fragility made real by the weight of his pack, a pack which, metaphorically, seemed to represent the weight of his endeavor and the pressure applied upon him by the Canyon.

FromDesert Viewwe watched George, through binoculars, inch his way down theTanner Trail, around the switchbacks aboveGardenas Butte, rest in the shade of a house-sized boulder, and finally reach his campsite three and a half-hours after leaving us. We watched him until nightfall, until the impending darkness made binoculars useless, trying to keep alive our last image of him as long as possible. In the immensity of the Canyon we regularly lost sight of him and had to look all over before finding his location again. His presence seemed negligible in the context of the giant chasm and he appeared at the mercy of the Canyon’s whim.

This was George’s 48th trip to the confluence. He would add two more to this stunning tally: a stop at the confluence during a river trip he joined as swamper in July 2001, his 49th, and the trip withLinda Brehmerdown theSalt Trail, his 50th and last, in August 2001. To my question as to why he chose to hike this water-less trail in the summer George answered, “Some like it easy, I like it hard.” In retrospect this may seem like a premonition. Maybe. After all, most everything in the Grand Canyon is bound to be hard sooner or later. What he meant I believe is that he liked a challenge, he like things which did not come easy and liked to feel resistance pushing back upon him.

The next day, after treating himself to sunrise onto theUnkar Delta, thePalisades of the Desert,Chuar Butte,Isis Templeand the North rim from one of the most amazing locations in the world, he broke camp and hiked down to the river. Alternatively hiking and dipping his shirt into theColorado Riverfor what he called “natural air conditioning” George followed theTanner Trailuntil its junction with theBeamer Trailand then all the way to the confluence.

Powell Point © George Mancuso

Powell Point © George Mancuso

George was in no hurry, having no place to go in particular and only the confluence as a destination. He would spend the time allotted by the first of his two permits in the park, then cross over to theNavajoreservation, spend a few days there and come back into the park for the length of his second permit. George did it by the book but liked to bend the rules. He saw nothing wrong with that and was a free spirit, one for whom rules and obligations became a burden at times.

Don’t get me wrong. George would never have done anything that would have either harmed someone or harmed theGrand Canyonin any way. He told me of instances in which he helped hikers come out of the Canyon while they were neither prepared nor equipped for the hikes they got involved in. He also told me of several instances were he picked up trash left behind by hikers too tired to care any longer about basic backcountry behavior.

But when it came to choosing between enjoying the Canyon and following the route laid out on his permits weeks ahead of time I think you know by now what his choice may have been. In July 2000 George came out of theGrand Canyonby hiking up theNew Hance Trailafter catching a ride on a commercial river trip at the Confluence and running the river down toHance Rapid. Carrying a pack lightened by two weeks in the inner canyon George knew he would make mince meat of a trail that he himself called a route. Little used by regular hikers theNew Hance Trailwas not only a challenge: it was an option that Rangers, who were by now looking for George, a day late to come out according to his permit, never considered. At the top George hitchhiked, got a lift from the first car he saw in over two weeks, got back to his truck atLipan Pointand drove home. He was fined $100 for being late on his permit and not following his intended route (he was supposed to come out via theTanner Trail), but could not be charged for the 2 day helicopter search since no one located him.

The Photographer

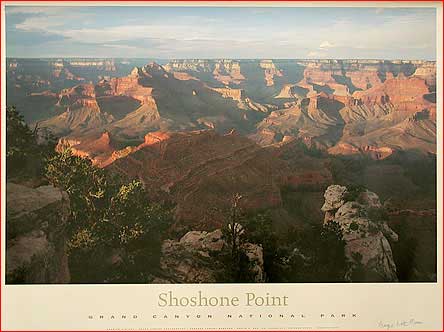

Shoshone Point © George Mancuso

Shoshone Point © George Mancuso

I have been told that there are two types of landscape photographers: those who hike to photograph and those who photograph to hike. In the first instance people are first photographers and second hikers. In the second instance the are first hikers and second photographers. My belief is thatGeorge Lamont Mancusoembodied both types at once. When he photographed along the rim he was hiking to photograph, hiking to get to the location where he wanted to create his images. I believe George had little interest in hiking along the rim except to get to a stunning overlook and photograph. He wasn’t carrying a hiking backpack at these times and took only minimum food or water. This was photography time, play time. It was also being with the tourists and he referred to the guard rail areas at the farthest point of the overlooks as “the cage.” George tried to avoid the cage at all cost. He tried to find a similar vantage from a location slightly off from the cage just so he wouldn’t have to compete with the crowd for tripod space.

Rim photography was pure photography for George. He would carry hisLowe Probackpack and take along hisGitzo Carbon Fibertripod. He would also bring an extensive arsenal of cameras:Contax RTS III35mm with a wide assortment of lenses;Pentax 645ziandPentax 67medium format cameras;Mamiya 7with assorted lenses and panoramic adapter;Linhoff 6×17panoramic camera. Those would not necessarily surface all at once — there’s only so much that can be carried and used at any given time! — but they were there in case they proved needed and they represent the cameras George used between 1998 and 2001.

By contrast, and again this is my personal belief, when he photographed in the inner canyon, along the trails and as part of multi-day hikes, George photographed to hike. During those times he was first a hiker and secondly a photographer. To me this explains why his inner canyon photographs, with the notable exception of “The Confluence,” do not have the captivating power that his rim views have.

Doing landscape photography well means being able to keep two things separate and at the same time being able to make those two things work together. The first is one’s involvement with the subject — in the case of George one could say one’s blinding passion for the subject. The other is being able to look at the subject in a two dimensional way, as an image, and therefore being able to remove sound, smell, and other sensual information to the exception of visual information. In a photograph that’s all which will be left — visual information — and, although the information conveyed by our other senses is important, any information other than visual must be translated as an element of the image.

In many ways this is a very introspective and meditative process, a process which requires being able to distance oneself from the subject while at the same time being able to respond directly to the changes in the light, the weather and the seasons. I believe George could do this on the rim and do it well. But when he got inside the inner canyon both his surroundings and his excitement overwhelmed his senses. In the inner canyon his ability to abstract himself from his surrounding and see the scene in front of him solely as visual information vanished. In the inner canyon George became an explorer, a trailblazer, a survivor. It wasn’t photography that was first for him any longer, it was theGrand Canyon.

The Accident

So what happened on August 8, 2001? What happened inBig Canyonthat took the life ofGeorge Lamont Mancusoand ofLinda Brehmer, his hiking companion? George had hiked down theSalt Trailat least two times prior to this day. Called a “trail” theSalt Trailis actually a rough route that starts on the Navajo side of theLittle Colorado Gorgeand dips straight down to river level in only a few miles of hiking. “Route finding abilities required” say guidebooks andNational Park Servicebrochures. “Tough legs and extensive Grand Canyon experience are a must” I would add. Prior to meeting his fate George had gone down this trail at least 2 times that I know of from talking with him: once in 2000 and once in the spring of 2001, this second time also withLinda Brehmer. On this second occasion, because Linda did not have the necessary experience to go down theSalt Trailwith a heavy pack on her shoulders, George carried not only his pack but hers as well, one on his back one on his chest. These are overnight backpacks, loaded with the necessary supplies and gear for a multi-day expedition in a remote area. And although he only carried both packs in the most critical areas — where loosing one’s balance because of the pack weight was a serious risk — this feat attests to his level of physical fitness. Most people could not go down theSalt Trail. Period. George went down with two backpacks. “Just give me a single backpack and I’ll show you what I can really do!” I seem to hear George say to me. And indeed, he would.

So what happened down inBig Canyon, a tributary of theLittle Coloradoupstream from theSalt Trailroute, that was tougher than this seasoned hiker? In all probabilities what happened is what we were able to piece together so far: a massive flash flood filled the narrow gorge with foaming mud, tree trunks and other debris, giving little or no warning, and this happened so quickly and brutally that retreat in the boulder-strewn gorge was impossible. I dislike the word impossible but in this case we are talking of physical impossibility. To escape the raging flood, to move out of Nature’s way, George and Linda would have had to fly and that was just not an option. Caught by surprise at theEmerald Pool, a place almost no one knew existed before their disappearance, and a place very few people have personally visited, they most likely heard the roar of water churning boulders and vegetation in a mad rush downhill and felt the pressure of warm air compressed by the torrential stream. This may have been their first warning, their first clue that something was about to happen: a breeze increasing to a rush of warm air caused by the pressure of air pushed down, forced forward by an incomprehensible mass of water rushing down the narrow crevice, bouncing from boulder to boulder and taking everything with it along the way.

The Confluence — © George Mancuso

The Confluence — © George Mancuso

Perhaps then, at that crucial time when their impending fate was just revealed to them, they felt this calmness which sometimes sets upon human beings just before drama unfolds. Maybe they experienced the peacefulness and the quietness that the mind creates as it slows down time to better prepare for the inevitable. A sort of timelessness that one would like to treasure but which one knows is dramatically temporary.

And then it must have come upon them. All of a sudden. Not a trickle followed by a stream followed by a river but all at once a raging, hard and murderous mass of water, rocks and trees. Contact must have been terrible, either with water, rock or wood and may have knocked them unconscious right away. Forced under water they may have fought their way back up only to realize they were against forces greater than they. Trees knocked them back down as they clawed their way up, boulders impacted their flesh, and bones broke under inhuman shocks. And then came the churning, rolling and rolling again in the river bottom, crashing against rocks and brushing by tamarisks bent by the flood. Finally, sand turned into mud covered them until they came to rest, forever still, covered by a blanket of ground sandstone, floatwood and ripped vegetation.

Linda’s body was found belowEmerald Pool, only a few meters downstream. However, George’s final journey was not over yet. Carried by mysterious forces another 6 miles downstream, forces which incomprehensibly navigated his body around house-sized boulders under which, in all logic, it should have become wedged, forces which did not allow the famed quicksand of theLittle Colorado Gorgeto play their favorite trick, George’s body found itself at the confluence of theLittle Coloradoand theColorado, buried under sand and debris, only a few feet away from the swift current of the river which carved theGrand Canyon. Why this current did not drag him further away, downstream and perhaps never to be seen again, no one can say. The fact is, and that is the only fact we have really, that his body ended up resting at the place he loved most, a place he had visited 50 times alive and one time after his passing. A place he loved so much that he had to come back to it one last time. As if superhuman strength possessed him at the time of death, as if his existence had culminated in one last Herculean effort, as if carrying two backpacks was nothing compared to the last task he had to accomplish, George, somehow, either by muscle or by will, managed to reach the place he called home. He was 46.

How do you say good-bye to a friend? The answer is, you don’t. Whenever parting is necessary the implication is that it is also temporary. The deeper your friendship becomes the shorter this temporary separation is implied. I don’t know if I put this properly, if I wrote it well, but I believe you will understand what I mean. I had to write the text that you just read because if I did not write it I would have felt as if I shorted out my friend. For a long time it was a blank page staring back at me and I knew that if I worried excessively about how I was going to write this I would never do it. This is a good-bye, the last good-bye. One that I never thought I would need to say.

Alain Briot

Chinle, Arizona

February 2002

This is one of a regular series of articles titledBriot’s View

written exclusively for TheLuminous Landscape

byAlain Briot

You May Also Enjoy...

Icelandic Portraits

On the first of two workshops which I conducted in Iceland in July of 2004 we stopped one morning atThe Black Churchon the Snafelsness Peninsula.

So You’ve Got It, But Do You Use It?

You’re familiar with the adage that the best camera is the one you have with you. For many of us today, our mobile phone