by Mark Dubovoy

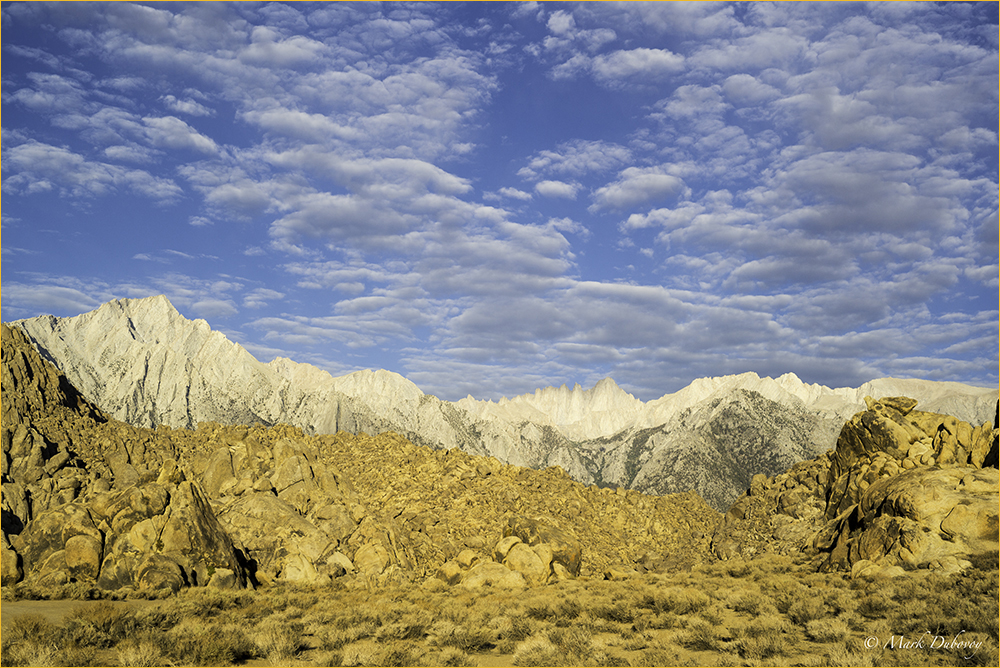

Mount Whitney Sunrise

Leica M 240, 50 mm. APO Summicron ASPH

What if…..

I believe that many of us have periodically wondered what would happen if management of one of our favorite photography companies told the design and manufacturing engineers to make the best product they could, with no constraints and no restrictions. In other words, no cost constraints, no engineering constraints, no manufacturing constraints, no marketing pressures, etc.

What would the product look like? How much would it cost? Would it ever go into production or would it follow the faith of most concept automobiles and simply remain an example of what might be possible but never introduced into the market as a real product?

The Venerable Summicrons

An old friend and great photographer that was one of my mentors and I always respected very highly, told me many years ago: If you want the best 35 mm quality possible, shoot your pictures with a Summicron. This was literally decades before I would be able to afford any Leica gear, but his advice stuck in my brain and when I finally purchased my first M camera, the first lens I mated it to was a Summicron. As the years passed, I tested a number of lenses and my friend was absolutely right, nothing was as good as a Summicron. I always felt that the 35 mm, 50 mm and 90 mm Summicrons were the best lenses of their respective focal lengths. The 75 mm Summicron came later and it is an excellent lens, but it is not a focal length I particularly like for my work.

It seems that over the last decade and a half or so, most of the emphasis has been placed on the faster Summilux lenses both, in terms of new models as well as in terms of marketing resources. In spite of this, I still like the Summicrons better. My advice is that if you can live with a maximum aperture of F/2, nothing beats the Summicrons in terms of image quality and compactness. I would recommend other lenses only if you absolutely must have a larger aperture or if you need a different focal length.

Having said all that, I sold my 50 mm Summicron a number of years ago and replaced it with a Noctilux because I was fascinated with the possibilities of shooting at F/1.0. Given the breathtaking high price of the Noctilux, I could neither justify nor afford keeping two lenses of the same focal length.

When the new Noctilux F/0.95 was announced, I sold my old Noctilux at a sizeable profit (this is the only time I have sold a used lens for more than twice what I paid for it) and I replaced it with the new Noctilux. The Noctilux is a fantastic lens wide open. It renders beautiful images. I was having so much fun shooting it wide open that I actually taped the aperture ring at the wide open position and called Leica to tell them that they should not have bothered with a diaphragm for this lens. It should have been a single aperture lens.

Leica’s response was that they had heard this same comment from quite a number of Noctilux users, but that the lens was truly excellent at smaller apertures. Sure enough, the secret was out: The Noctilux is one of the best lenses in existence at apertures between F/2 and F/5.6. I would not hesitate using it as a world class general purpose lens at those apertures when needed.

When I heard that Leica was introducing a new50 mm Summicronthat came out of an all-out effort with no holds barred, I became curious but I thought the expected price of approximately $7,300 US dollars was lunacy. I then looked at my 35 mm and my 90 mm lenses and realized that I purchased my 35 mm Summicron ASPH in 1996 and my 90 mm APO Summicron ASPH in 1997. Both lenses are over 16 years old and they are still state of the art. I have not seen either a 35 mm lens or a lens close to a 90 mm focal length from any brand on any mount that can match them in terms of image quality, mechanical finesse or compactness. So when Leica makes the statement that their new 50 mm lens establishes a new benchmark for years to come, it is not hard for me to believe that this is indeed the case. The Summicrons seem to last for decades and remain the benchmark for the state of the art.

It is worth noting that the previous 50 mm Summicron remains in the Leica lens line because it is such a good lens and the price is much lower.

Asilomar

Leica M 240, 35 mm. Summicron ASPH

The story of Leica’s new50 MM. F/2 APO Summicron ASPH

There are a number of different versions of the story of this lens, so to get to the truth I decided to contact Leica and get the story “from the horse’s mouth”:

The original 50 mm Summicron was designed in 1956. It was refined in 1969 and received its next redesign in 1979. Although the lens has been massaged in a few areas like better coatings, the basic design has remained unchanged for over 30 years. I think it is amazing that a lens design could remain state of the art for so long in this day and age. It is a true testament to the extreme dedication to quality in Leica’s optical department.

I am told that Peter Karbe, head of Optical Systems Development at Leica had studied all the old notebooks on the 50 mm Summicron very carefully and had a deep desire to try to improve the lens. However, it was clear that the return on investment for a new lens was simply not there, because the existing Summicron was so good that there would not be a significant enough difference in resolution with current color sensors to justify the development program and the price difference to customers. Therefore, every attempt to design and build a new 50 mm Summicron was turned down.

(Note: It seems that resolution is the only area that many testers and many photographers care about when it comes to a new lens. However, there is A LOT MORE than just resolution when it comes to image quality. More on this later).

The event that changed all of this was Leica’s decision to introduce the Monochrom. Since the Monochrom is B&W only, the sensor has no color filters and no Bayer Matrix pattern. Therefore, the resolution goes up significantly because unlike color sensors, each photosite produces one pixel in the final image. With the increased resolution of the Monochrom, the difference between the old lens and a new one could be much more noticeable, provided the new lens was up to the task.

My understanding is that Peter Karbe was given the dream command from management: Design and build the best 50 mm lens you can humanly make. Absolutely no restrictions and no constraints. The result is the newAPO Summicron ASPH.

Sunrise Near Lone Pine

Leica M 240, 90 mm. APO Summicron ASPH

The Best Lens In the World Syndrome. Are We At A Crossroads?

I am convinced that we are at an exciting crossroads in the history of photography.

In general, our camera systems today are lens constrained. What I mean by this is that the best lenses we use are very close but not quite as good as the sensors in our cameras. One example that comes to mind is that we can compare lenses and see and measure the resolution differences in our cameras. This means that the sensors have better resolution than the lenses. If all our lenses had significantly higher resolution than the sensors, we would not be able to see or measure these differences as the sensor would be the limiting factor.

(This makes clear the reason why the development of a new Leica M 50 mm lens was turned down in the beginning, since the resolution of the older Summicron is very close to the resolution of current color sensors).

But things are changing!!!!!

This is the first area where theLeica 50 mm APO Summicron ASPHestablishes a new benchmark. As far as I know, it is the first lens that easily exceeds the resolution of current camera sensors. This is of extreme importance, because as future camera bodies improve (including increased resolution), the resolution of the image with this lens will also improve, while the resolution of the final image with lesser lenses will not.

This brings me to what I call “The Best Lens in the World Syndrome“: I believe that over the next few years we will see lots of articles, reviews and marketing materials claiming that this lens or that lens is either “the best lens in the world” or “the best lens I have ever tested“. This is because lens manufacturers have taken notice that camera sensors will start to exceed the quality of current lenses to an extent that there is a significant revenue opportunity by producing better lenses.

It is no surprise that Leica is leading the pack. It is also no surprise that Zeiss is also putting significant resources in this area. I would expect that when Zeiss introduces their upcoming 50mm Distagon for Canon and Nikon we will see all kinds of rave reviews and bold statements about this lens as this lens will most likely establish the Zeiss benchmark for the future.

So folks, start saving your pennies. We have a whole new generation of lenses coming our way in the next few years and they will make a big difference as sensors continue to improve.

May we live in exciting times; 35 mm image quality is getting ready to take an important step forward in quality.

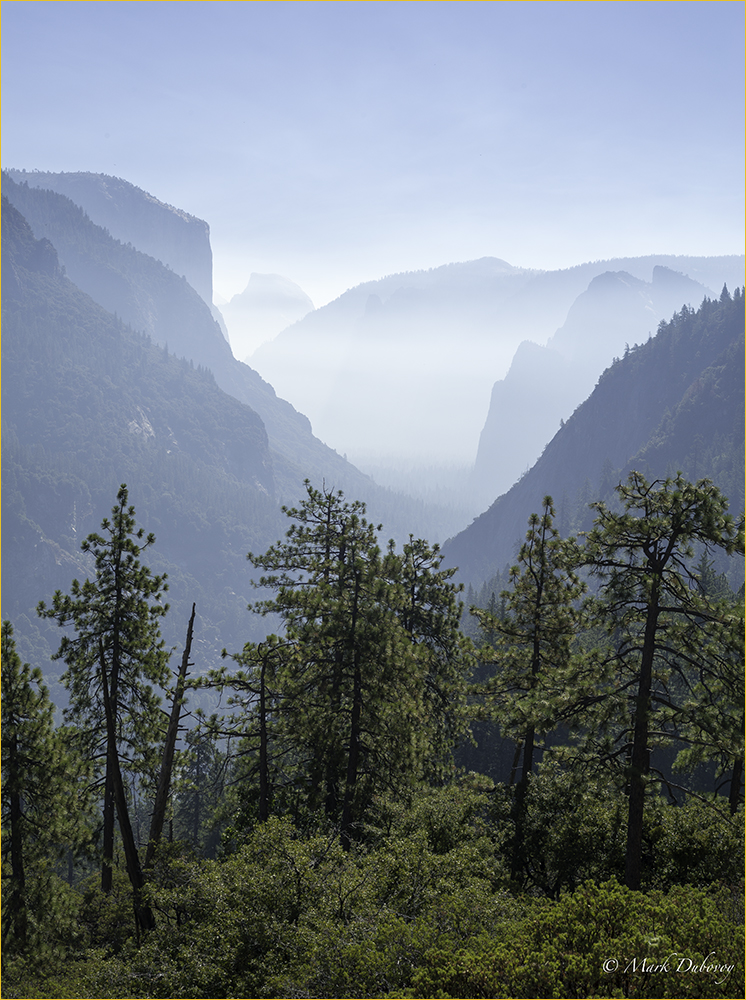

Early Morning Mist, Yosemite

Leica M 240, 50 mm. APO Summicron ASPH

How Good Is It?

Well, curiosity killed the cat. I could not stand it any longer, so I decided I just had to test and perhaps purchase this new Leica lens. But first I had to perform the usual ritual of self justification regarding price. I am sure many of you know the drill of the many ways to justify prices to oneself (and often times the spouse or significant other also). Suffice it to say that many Leica M lenses are now in the $7,000 dollar range (Gulp!).

So once I was done with the self justification, I got in line and placed an order. One of my favorite dealersBear Images Photographicin Palo Alto CA finally came through for me and with great trepidation I unpacked the lens. I was immediately struck by two things:

Lens Hood

Oh yes, perhaps a simple thing, but critical when it comes to lens shading and lens protection. One of my pet peeves is that the vast majority of lens hoods provided by manufacturers are crap (I am being gentle here, a stronger word might be more adequate). With only one notable exception (the PhaseOne/Mamiya 300 mm lens), all other Japanese lens hoods I have ever used are pure crap. Sad to say, but I can state without hesitation that all of the Japanese 35 mm lens hoods I have ever seen or used are crap. Nikon, Canon, Sony, Fuji, Pentax, Sigma, Tamron, you name it. These companies just do not get it, they do not seem to care and they certainly do not listen to those of us who have been talking, nudging, cajoling, writing, jawboning and screaming about this for decades.

Every single removable reversible lens hood I have ever tried is crap. Unfortunately, this also includes the Leica S lens hoods and some Schneider and Zeiss lens hoods. All removable reversible hoods I have seen are clumsy, hard to put on and take off, usually way too thin and made out of lousy materials, easy to mount crooked and get stuck and so on. They also take an inordinate amount of time to put on or take off. It is a bad design to begin with and to make things worse they are usually badly made with inferior materials. I do not understand how companies that are supposed to be focused on quality and usability like Leica, Zeiss or Schneider would allow such crap to be mated with their lenses.

In years past, the most consistent exceptions to this bad lens hood syndrome have been the Leica M and the Leica R lenses: The lens hoods for normal and longer focal lengths are built in and all you have to do is pull them out (some of them also lock into position with a slight twist ) and the lens hoods for wide angles are rectangular, remain on the lens at all times and have a matching rectangular lens cap.

I am happy to report that the50 mm APO Summicron ASPHhas the best lens hood I have ever used. Simple and brilliant.: It is built into the lens, and it is designed to look like part of the barrel. All you do is grab it and turn it a fraction of a turn. As you turn it counterclockwise it pops out. As you turn it the other way it goes back. It is self locking (thus protecting the front element) in any position including partial extension. As I said, simple and brilliant!

(For the mechanically inclined, this is done by having two helical channels carved on the inside of the hood with corresponding tabs in the barrel).

The lens is supplied with two lens caps, one plastic and one metal. The metal lens cap looks retro, but the materials are better than the old Leica metal caps. It is the best lens cap I have ever used. Smooth, easy to take off and put back on and provides terrific protection. I have no use for the plastic cap.

Because the metal lens cap fits over the hood, you can grab the cap and with a small quick rotation and gentle pull you extend the hood and take the cap off. The reverse motion caps the lens and retracts the hood. Whether the camera is hanging from its strap or on a tripod, it takes literally about half a second and only one hand to extend the hood and take the cap off without even looking. In other words, you can go from having the lens hood retracted and the cap on to ready to shoot in about half a second. Good luck trying to do that with a typical removable reversible lens hood…

Construction Quality

The other thing that immediately struck me was the fit and finish, the mechanical design and the construction quality of the lens. The lens is extremely compact, but is perfectly designed for human hands. It has a reassuring heft and a feel of solidity that oozes quality. Leica M lenses are traditionally exquisitely finished, but this one is a cut above. The fit and finish, the quality of the engraving, etc. seem to have been taken up a notch. Both, the focusing mechanism and the aperture ring are the smoothest I have ever experienced. Again, these seem to be a notch above prior M lenses.

Before taking my first picture it was evident that this lens sets a new benchmark for mechanical design and quality that surpasses any other lens I have tried to date.

The Elephant In The Room-Image Quality

By now you may be getting impatient about the elephant in the room: Image Quality.

I have a confession to make: When I first got the lens I spent the better part of a week taking pictures of thin wires, colanders, shiny objects, beauty products with extremely saturated colors in bottles with metallic caps, printed circuit boards, distant trees, etc. I tried the harshest and the softest lighting conditions I could find. I took pictures of grids to see if I could find distortions. You get the idea. Basically I was trying to “break the lens”. In fact, I was trying to break the M 240/50 mm lenssystem.

I had zero luck. Not even a slight Moiré pattern or slight distortion of any kind. No visible sharpness differences across the frame, no visible chromatic aberration, no visible distortion of straight lines, gorgeous specular highlights, amazing contrast and saturation, barely visible (you really have to look for it) light fall off at the corners wide open, completely gone by closing one F/stop. In other words, all I got was pretty much utter perfection: Extreme sharpness, terrific color, amazing high contrast, beautiful saturation, complete uniformity from edge to edge, exemplary Bokeh…Stunning performance. Better than any lens I have tested before.

Did I compare it to other 50 mm lenses? Yes I did, particularly to my Noctilux. The Noctilux for example comes close in resolution (between F/2.8 and F/5.6), but nowhere near the Summicron in terms of lack of chromatic aberration, local contrast, color and several other important criteria that determine how the final image looks.

Even though images shot with the new Summicron clearly look better than those shot with the other 50 mm lenses, Leica was correct in figuring out that the difference in resolution is subtle when shooting with an M240. The resolution difference is there but it does not “pop out at you”.

This got me curious again, and Jim Taskett, owner of Bear Images, managed to obtain a loaner Monochrom for me to use for a few days. When I compared resolution using the Monochrom, there was a very large difference between the new Summicron and the Noctilux. I was quite surprised, it was much more than I had anticipated. It does not feel like an incremental improvement in resolution, it is a big jump. So the whole story makes perfect sense.

For B&W shooters, the combination of the Monochrom and the new Summicron can only be described as extraordinary. The images are truly gorgeous. Note the exquisite tonal rendition in the image below which was shot on a whim under standard fluorescent lights when I walked into the kitchen. Also, notice the extreme resolution and local contrast (including the fine texture and minute scratches in the salt and pepper shakers) in the section enlarged to 100%.

In the Kitchen

Leica Monochrom, 50 mm. APO Summicron ASPH

Section of above image at 100%

Originally I was going to concentrate on test and comparison images in this article, but that is not what I want to focus on and I am sure you will find plenty of test reports in other places.

So, instead of boring you with test images I decided to take the M240 body and my 3 Summicrons (35mm, new 50mm and 90 mm) on a field trip. I took them first to the beach and then to Yosemite and the Eastern Sierras to see how the system would perform in the field.

But before we get to that, I would like to discuss a few more things regarding image quality and lens design.

It Is NOT All About Sharpness

It is no surprise that in our world of instant gratification, 10 second sound bytes and Tweets, people that are not particularly knowledgeable or sophisticated seem to rate lenses in terms of a single word: “Sharpness”. If a lens is “sharp”, that is all they care about and they are happy, if it is not, they think it is inferior.

My guess is that they probably do not even realize that the concept of “sharpness” is quite complicated and many scientific essays have been written on the subject. It is not a word that accurately describes a measurable parameter: No one can tell you whether “the sharpness of this lens is 17 or 23”. Sharpness is a term relating to how the human brain perceives an image. Popular magazines make things worse by erroneously confusing their readers into thinking that resolution and sharpness are the same thing.

In my many travels as a photographer I have come across “incredibly sharp” lenses that have not just bad, but actually horrific image quality. They are “sharp” indeed, but so many other things are bad that some of these lenses really suck.

More discerning and more knowledgeable photographers tend to focus on multiple parameters such as resolution, contrast and accutance (all of which contribute to the perceived “sharpness” of an image), plus other parameters such as, saturation, MTF curves, distortions, etc. This is the correct way to look at the performance parameters of a lens. While all these measurable parameters are a terrific way to learn a lot about a lens, they do not tell the whole story. You cannot measure Bokeh for example; you just have to look at the out of focus regions in an image with your own eyes.

For my purposes as a photographer, I like to evaluate lenses in terms of a variety of parameters, all of which contribute to “the look” of an image shot through a specific lens. Some of these parameters are measurable, some are not. I am interested in how the final imagelooks as rendered by a specific lens. I have little interest in overly simplistic evaluations such as whether a lens is “sharp” or not and I am not satisfied with incomplete evaluations such as looking at the MTF curves and nothing else.

Besides resolution, contrast and accutance, each an every lens has a specific way in which it renders color. Some lenses have warmer colors, some lenses have colder tones, some have more accurate colors than others, some deliver superb color saturation while others do not, some exaggerate certain parts of the spectrum, some deliver wavelengths well beyond visible light that might affect the sensor, some have chromatic aberration while others have minimal chromatic aberration, some have more pincushion or barrel distortion than others, ditto for spherical aberration and so on.

Different lenses have different characteristics in terms of light fall off at the edges, some have quite uniform resolution across the frame while others are much sharper in the center versus the edges, some have great diaphragms and diaphragm location which tends to render beautiful specular highlights and nice Bokeh while others are downright ugly and everything in-between, some lenses have better coatings than others and so on and so forth. You get the idea.

A number of years ago I started to think about the fact that not all lenses have a plane of focus that is a flat plane. The plane of focus of many lenses (actually most lenses) is a curved plane and the shape of the curve obviously affects the look of the image.

Let me take this further to a thought that might be almost scary: With the exception of the elements that are precisely in the plane of focus, everything else in an image is out of focus. I do not know about you, but this means that the overwhelming majority of elements in my images start out being out of focus. In my images I often try to bring most of these out of focus elements back to a zone of acceptable sharpness using depth of field, but out of focus brought back to acceptable sharpness is not the same thing as in focus to begin with.

(Sorry to use the word “sharpness”, but this is standard terminology when talking about depth of field. As I and others have discussed in a number of articles, “depth of field” and “acceptable sharpness” are subjective concepts based on human observation).

Therefore, one of the most important characteristics of a lens (for me anyway) is how objects that are out of focus look both, when left at different levels of out of focus as well as when they are brought back to acceptable sharpness by using a smaller aperture for proper depth of field. No matter how many charts or technical measurements you look at, when you ask these questions there is no number or set of measurements that can give you the ultimate answer. You have to shoot some pictures and look at the images.

Bottom line, lens evaluation is quite complicated and in my view boils down to first carefully studying all the measurable parameters followed by extensive field testing shooting one’s own images. Without shooting and looking at images, you really cannot know many things about how a lens is going to perform.

Furthermore, as you can clearly see, lens design is not pure science. There is a lot of art that goes into it. And the art is further complicated by manufacturing issues such as types of glass or coatings available, manufacturing tolerances, etc.

Top quality lens manufacturers such as Leica, Zeiss, Schneider and Rodenstock rely very heavily on their many years of experience and tradition developing the art of lens design, the art of specialty glass manufacturing and many proprietary manufacturing processes. They do not rely just on computers or manufacturing automation, heavy human intervention is required. Some of the major mass manufacturers such as Nikon and Canon also rely quite heavily on the art and their own tradition versus software and computational power combined with factory automation alone. For example, Canon has been refining the art of Fluorite elements for long focal length lenses for many decades.

For those of you who might be interested, there is a section of the Leica website dedicated to the50 mm APO Summicron ASPH. If you clickhere you can find a short video with Peter Karbe, read what Leica has to say about the lens, click on the links on the far right to peruse the technical data such as the MTF curves, etc.

The image below was shot on a smoky day because of nearby fires. I was deep in the forest and the light was quite harsh. I believe that the new 50 lens rendition of the close trees in the foreground versus the hazy rock in the background is spot on, particularly given the harsh lighting conditions. Also, the amount of detail captured in the rock is just right.

Below the image is a section of the upper left corner enlarged to 100%. No sharpening was applied to the original. This gives you an idea of the resolution, high accutance, high contrast and lack of light fall off at the edges that this lens delivers. I have shot many pine needles and branches with digital cameras and I must say that this is the first 35 mm camera/lens system that does not show any artifacts and zero visible chromatic aberration in the pine needles and at the edges of fine branches. If you see any artifacts, they are JPEG artifacts. Trust me, there are no visible artifacts in the original files.

Forest and Rock, Yosemite

Leica M 240 with 50 mm. APO Summicron ASPH

Crop from upper left corner of above image at 100%. No sharpenning was applied to the original file

In The Field

I felt almost like a Martian taking such a small camera and three small lenses in the field. I am so used to carrying MF gear and a sturdy tripod that it felt liberating and disconcerting at the same time. It very quickly became fun to shoot with such a small outfit and I found myself getting a little lazy in terms of using the tripod. I ended up doing quite a bit of shooting handheld.

Did I learn anything? Yes, one always does. Here are the major highlights of what I learned:

— Rangefinder focusing never ceases to amaze me. It is deadly accurate and extremely fast. As I had discovered before, the M 240 EVF is worthless for focusing and looks very dark compared to the rangefinder. The methodology of using the rangefinder for focusing and then the EVF for framing still feels like the quickest and best way to shoot landscapes.

— The M 240 and the three lenses performed flawlessly. They are all superb, but the new 50 is really special. It is, as I have said before, a cut above all prior 35 mm lenses I have used.

— I do not mean to be repetitive, but it is important to reiterate that the look of images shot with the new lens is superb. It does bring memories of the other Summicrons, but it is different. It is sort of like having a cousin that may bear some family resemblance, but is a superstar athlete. The new 50 is simply in a new league, and does indeed set a new benchmark for image quality.

— I have found in my prior tests that when shooting handheld, for maximum resolution one needs to be at least at triple the inverse of the focal length in order to be safe. In other words, for a 100 mm lens the minimum safe shooting shutter speed for maximum resolution is 1/300th of a second. I have found this time and time again with every system and every lens I have tested. Whether the lens or system has image stabilization or not, I keep getting the same result. The Leica outfit proved this to me in spades one more time.

I do not claim to have tested every lens and camera combination, so this is not the ultimate gospel. Test your own gear! All I am saying is that this seems to be very consistent with all the cameras and lenses I have tested so far.

— I have also found in the past that a good rule of thumb is that for 35 mm systems diffraction starts to rear its ugly head at F/8. Given the extreme resolution of the new 50 mm lens, the difference between F/5.6 and F/8 is quite noticeable. I have never before seen the effects of diffraction so clearly. While the lens is still terrific at F/8 (those of you who love to spy on metadata will be surprised to find out which image in this article was shot at F/8 :-)) one should bear in mind that anything beyond F/5.6 starts to degrade the image. If you shoot with a 35 mm. camera, I suggest you always keep this in mind. My usual recommendation still stands: If you need a smaller aperture because of depth of field, and it is the only way to get the shot, then get the shot and worry about diffraction later. On the other hand, if you have the choice, stick to F/5.6 or wider.

In terms of the50 mm APO Summicron ASPH, I do not think I will ever shoot it beyond F/8, it just feels like sacrilege!

— I have made a number of prints from my images at 20, 24, 30 and 36 inches in width. The M 240 images with the new lens make magnificent prints up to 24 inches. Definitely top notch exhibition quality. At 30 inches they are still very good and would be exhibition quality for many folks, but not for me; I guess I am jaded by being used to the quality I get out of a PhaseOne back with an ALPA camera. By 36 inches they are still very good if viewed at appropriate distances, but “pixel peepers” would find that at close distances the prints start to show the sensor limitations.

This answers the second “elephant in the room” question for those of us who shoot MF: Can this setup replace MF in terms of image quality? The answer is no. There is no 35 mm system I know of that can replace MF, but an M 240 with this new lens sure gives MF a run for its money in prints up to about 24 inches in width. I showed the prints to a few very knowledgeable photographers and they thought the prints came from my ALPA/PhaseOne outfit.

Conclusion

The 50 mm. APO Summicron ASPH is a new benchmark in optical performance, design and mechanical excellence. But beyond that, it is the first indication of a significant change in paradigm moving forward.

The old paradigm we have been living under is that we can wait for the next great camera and enjoy it using our existing lenses with it.

I believe this paradigm is beginning to change. As sensors continue to improve, they will exceed the capabilities of current lenses by a large enough margin that we will be forced to replace our lenses if we want to take advantage of the new improvements in imaging sensors.

Leica has thrown the gauntlet. They have introduced the first lens that easily exceeds the resolution of their latest color camera. Zeiss is not far behind and Rodenstock and Schneider continue to introduce new MF lenses with significant improvements.

It will not be long before Nikon, Canon, Sony and the other large manufacturers follow suit.

Therefore, I would suggest that you start saving your pennies because we are about to enter a new era in image quality and it will demand not just new camera bodies, but also a new generation of glass.

This Lens Is Available For Purchase at B&H byCLICKING HERE

Mark Dubovoy

August, 2013

You May Also Enjoy...

Adaptalux Studio

FacebookTweet How I developed, improved, manufactured and planned for the future using Kickstarter funds. Become part of the venture with Adaptalux, back their latest campaign