By the autumn of 2016 I was so disillusioned with landscape photography, I was nearly ready to quit. Probably the two things that stopped me from doing so were the fact it’s my career and I have a dogged determination to enjoy my life.

At that stage I was running perhaps 25-30 weeks of workshops a year, and anyone who does that knows how demanding it can be. There is a constant pressure to perform, to find interesting perspectives, or revisit locations you have been to hundreds of times, whilst all the time managing other people’s expectations.

I had scheduled a couple of months off during the winter and had some lofty ideas for getting out in the snow and making some new images – for me!

Of course, the Scottish weather rarely does what is is supposed to do, and after 5 weeks of constant westerly gales, mild temperatures, and horizontal rain, I was feeling very, very down.

As I trudged around Uig Bay on the west coast of the Isle of Skye, doing my 1st January bird count, I realised, for the sake of my sanity, I needed to get off the island and find somewhere dry! 3 days later I was on a flight heading west across the vastness of northern China for 3 weeks of exploring one of the most arid places on Earth, the Gobi Desert. Little did I know how much my life was going to change for the better.

A Brief History of my Time!

Spin back a few years, and I had been living in the Far East and China for over a decade; Malaysia, Thailand and Borneo, but mostly in the South West Chinese Province of Yunnan, and even a time in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet.

When I first got back into photography in my 30’s, it was my love of birds that was the stimulus. Inspired by the incredible bird images being made with new digital cameras, I went out and bought a 300mm f4 lens and a Canon 10D. I quickly realised the 300mm was not going to cut it, and soon enough I had a 500mm f4 on Canon’s flagship full frame 1Ds.

At the time I was self-employed, which meant I could devote considerable time to learning the craft: How to expose, focus, compose, and as importantly, understanding bird behaviour in order to predict and pre-empt movement or action. I recall quite vividly the feeling that I had found something special, and self-actualising.

In the autumn of 2004 I was visiting friends in Banff National Park, and having seen some nice landscape photographs in a local gallery, decided to drive down to Calgary and buy a 17-40 lens and some filters. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing, but pointed my camera at stuff that caught my eye and inspired me somehow. One night, under a full moon I revisited Vermillion Lakes and made my first night photographs – again, completely devoid of technical know how, or wisdom. I did know however, that shooting at night was addictive, and I was alone down there, rather than surrounded by other people as I had been at sunset.

By 2007 I was considering a career change and felt that landscapes rather than birds would be a more prudent move, and from then dedicated all my time to learning all I could about our craft. One side note is that bird photography had ruined birding for me, and I couldn’t just enjoy watching them, or being fascinated by them. It was all about “the shot” – I had lost a love for something that I had had for 35 years.

The Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau provided me with a fierce learning ground and I was working most nights at above 15000 feet trying to make images in the dark. The lack of learning material made progress slow, and I decided to embark on writing my own manual on Night Photography, and in the spring of 2012 I published Seeing the Unseen – How to Photograph Landscapes at Night.

The Harsh realities

My passage into the full-time professional arena was complete and the rest is, as they say, history! Or so one would think. In fact what I found was that in the coming years I was becoming more like everyone else and less like myself. The pressures to be popular, an influencer forces one into a homogenous battlefield where the trends rule. I was chasing the same conditions as everyone else, often in the same locations, and although I was successful, I was finding myself withdrawing from myself and becoming someone I don’t necessarily like, or admire. Around that time, in the mid 2010’s Social Media was really becoming the driving force for image-making, and it seemed to become a very competitive environment; with scores, rankings, likes, subscribers and followers being the primary business metrics. I was very competitive in my earlier life, and the whole scene was very negative to me. Waking up in the morning and the first thing on my mind being “How many likes on Insta did my shot get?” This is not a healthy lifestyle.

Desert Epiphanies

If you’re still reading, thanks for your patience! We can now pick up where we started; on a flight into the Gobi Desert. The first impressions were ones of shock and awe: It was January, and -26 Celsius (-15F) – not the best weather to be camping out in, but invigorating! We’d employed a driver to take us deep into the southern side of the Gobi, somewhere that basically nobody goes. This driver was the first to take a 4×4 in there and was a genius at navigating the 1600 foot high sand dunes, with hidden lethal pits, daredevil roller coaster climbs and manic descents.

Camping on the summits and waking to the total silence of emptiness was just incredible. Photographically though I was at a complete loss. Over the preceding years, I’d been honed into a wide-angled lens shooting machine by a decade of like-driven photography and considered myself to be pretty good at it.

In the desert it just didn’t work and I was out of my comfort zone. As it happens, exactly where I needed to be.

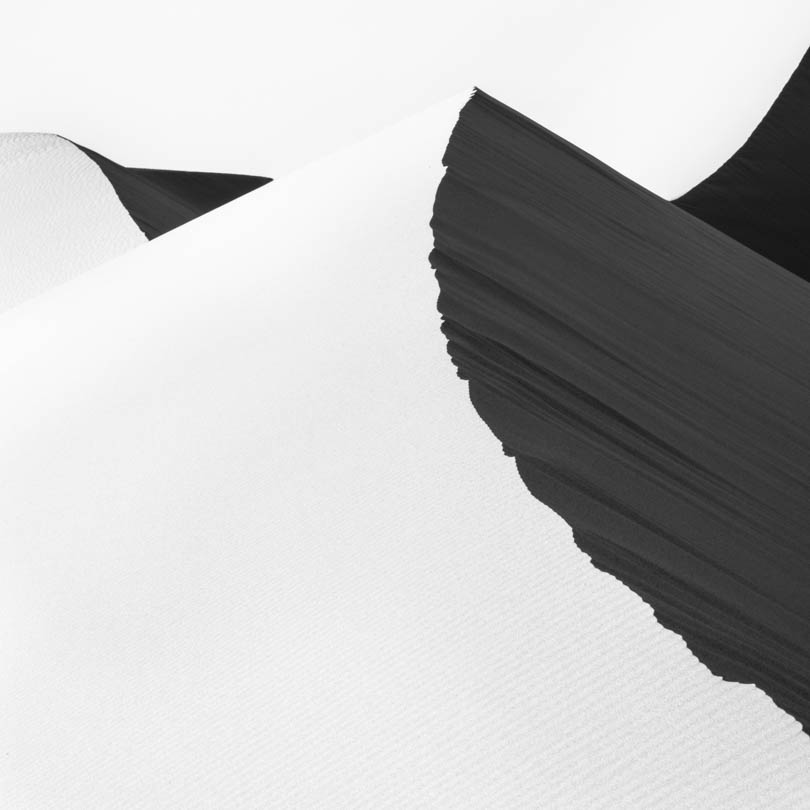

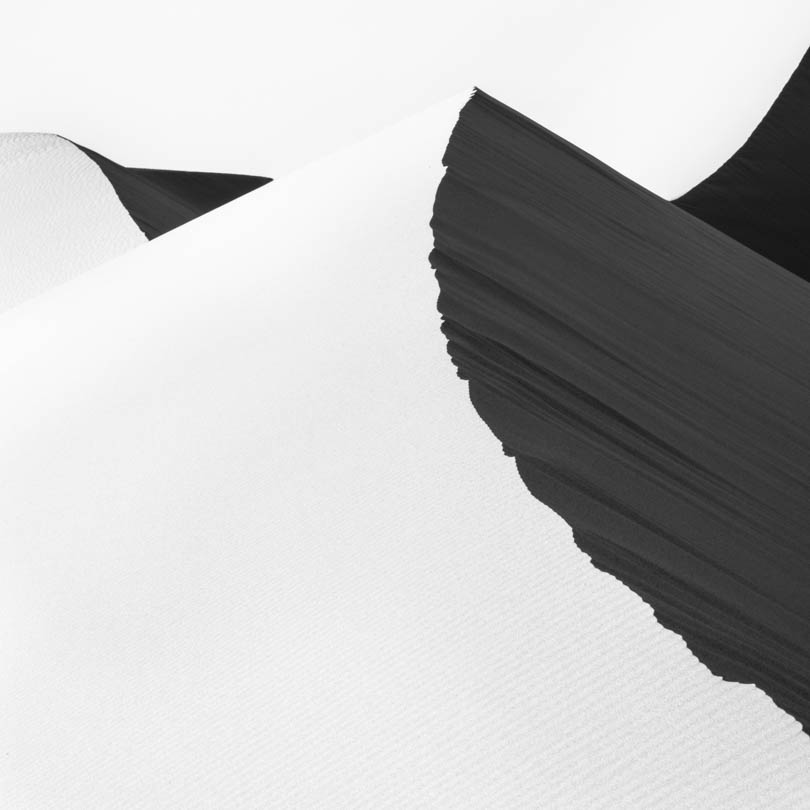

I decided to surrender to it, packed the 14-24 away in my pack and took out my 80-400 instead. It appeared to me that everything I had ever learned about composition didn’t work here. The term subject seemed in some way to trivialise the experience, and apart from a few tired, dried and stunted bushes, there was only sand.

Instead of looking for compositions, I began to allow my intuition to guide me. I popped the camera in AV mode, pushed the ISO to 400, VR on and an aperture between 5.6-7.1

With this rig I found I could handhold and began a process of FEEL | RECOGNISE | RESPOND

I allowed the landscape to tell me where to point my camera and I challenged myself to take all thinking, rationalising and analysing out of the equation. I thought nothing of final images, popularity or anything beyond my own experience with the landscape. There was no concept of visualisation, and I began to shoot from the gut. Ironically, this was the first time I had done this since that autumn in 2004 when I started making landscape images based on the very same conditions of intuition.

Isn’t it mysterious how society wants to make us all the same, living to the pulse of someone else’s heartbeat. I spent the long hours of night alone in my own head, freezing, but questioning everything; from my own existence, to the concept of societal aesthetics and homogeny. Here I was, probably the first westerner to walk on these dunes, let alone photograph them, and I had free rein.

The first compositions to present themselves, were quite straightforward, simple relationships of curves and lines. Juxtapositions of light and shadow, line and form. I pointed my camera at them and allowed the frames to settle themselves, somehow trusting that my innate sense of balance, harmony and flow would take over.

The other great liberation was from the technical demanding shooting style of the wide-angle. As soon as you want everything in the frame, the more we have to deal with focus and exposure extremes.

Very few of the images I made on that first trip (or the subsequent 6 trips!) required that level of technique; focus-stacking or exposure blending.

Within a few days I was truly hooked on the desert experience – the freedom to drive off road in any direction; in many cases 100’s of miles from the nearest road, or other humans. We saw a few camels, some exotic birds like Mongolian Ground Jay, and a fox! Otherwise, it was just empty sand.

By the end of that first reconnaissance, I had conditioned myself to a new way of seeing, but it was time to get back to northern Europe and pick up the workshop season again.

The first trip was to Iceland, and I was curious to see if my new passion for the innate would translate to another environment.

I’d been to the island a dozen or more times, and I was excited to discover that I had a very fresh perspective on the place. The relationship felt more intimate, genuine and emotional. I could lose myself easier, hearing the quieter voices that were speaking to me. A sense of resonance began and has not left me since.

Immediately after the workshop I had to travel to Florida to deliver a presentation at a large conference and I began to rationalise and make notes on these discoveries, which to me, felt life-changing.

I began work on a book that somehow pulls it all together in a strong statement of intent on how I aim to move forward, and also how I teach photography. I published that book (Luminosity & Contrast) in the spring of 2018.

Luminosity & Contrast

These are just two simple words, and I am sure we all have our own relationships, opinions and beliefs surrounding them and their meaning. I had to smile this morning as I began writing this article, as I recognised the word luminous in the name of this website.

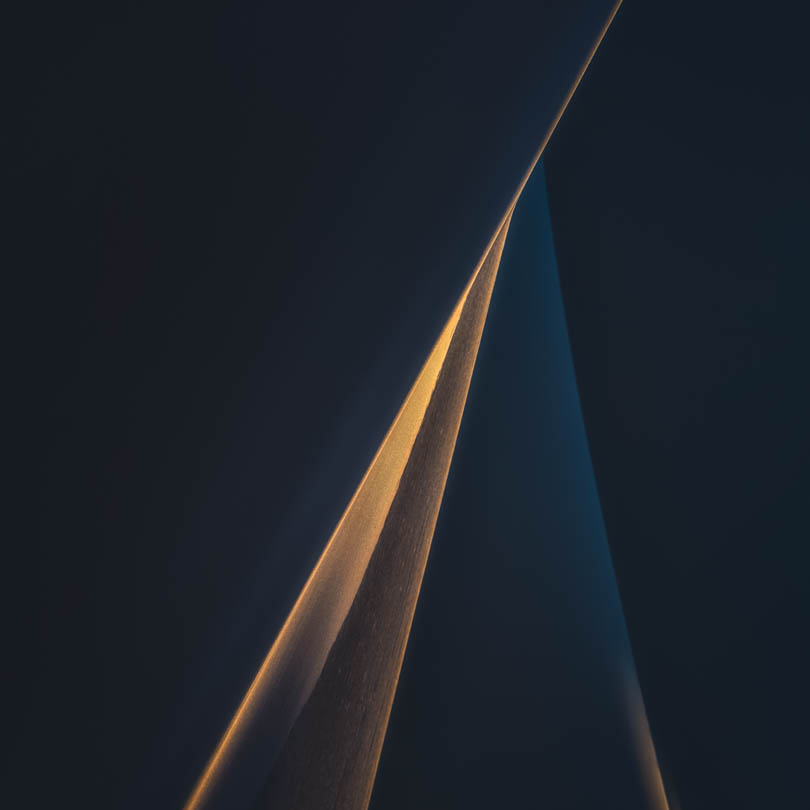

The more I walked the landscape, sat and looked, really looked; not just seeing, but feeling and listening, the more I realised that there were always certain triggers present that caught my attention. These turned out to be:

LUMINOSITY | CONTRAST | GEOMETRY | COLOUR | ATMOSPHERE

There is something joyful about luminosity and there is something engaging about contrast. Our human brains seek order, form and understanding in what we see. In the past it kept us alive, and in fairness, even today it does. In the realm of aesthetics and art, luminosity and contrast ask us to look, they tease us to engage. Arrangement in the frame is what we conventionally call composition, but each scene to us is unique and we can make obvious or obscure articulations on them, that only we truly understand.

Luminosity not only tells us where the brightest areas in a scene are, but how light or dark we want to process the final images. High Key/Low Key, moody and melancholy, or bright and optimistic. We’re opening up to an emotional lexicon that transcends technical limitations.

Contrast covers a broad gamut, from global to local, details and textures, through to mists and fog. Atmosphere is essentially a lack of contrast.

In the book I poured both my thoughts and emotions, for I soon discovered that my relationship with the landscape was no longer measured by popularity, likes or fame; it was based on emotions, feelings, my own personal development and quality of life. My images became snapshots of moments of my life when I was truly engaged with the world in front of me. While in the desert I had started to meditate in a formal way, practicing noticing when my mind wandered and centring my focus back on breathing. I found that I could enter that same state of non-judgement with a camera in my hand.

I continue to explore the concepts of judgement and expectation, both externally and internally. I delve into my own unconscious with the passion of a rabid spring-cleaner, throwing out the tired old beliefs I had lived for years, unknowingly building a cage for my creativity. It was not until I blew the smoke away and realised I had created a box based on my own fears and expectations, that I became truly free.

Seeing the world not as things, but as a spiders web of interconnecting luminosity and contrast changed my relationship with the world for the better. It’s not just another rock, or another tree, it is fascinating phantasmagoria or luminosity and contrast; miracles in their own right, perfect in their own form. It is us that labels, judges and has opinions of like or dislike; nature doesn’t care and ultimately our joy, or lack thereof is in our own hands.

BIO: Alister Benn is a Scot who lives and works in a remote corner of the west of Scotland with his partner Ann Kristin Lindaas. He makes anonymous images and continues to explore the relationship between himself and these innate sketches of the landscape.

He is the author of a number of eBooks and expressive processing videos.

Alister runs a YouTube Channel: Expressive Photography

Website: https://expressive.photography

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/c/expressivephotography

Insta: @alister_benn