By: Jack Perkins

Much. Much.

Call it symbiosis. (I know. I hate the word too, but it so aptly describes the artistic interaction possible between painters and photographers that I can’t avoid it. Forgive me.)

For several years I’ve been artistically engaged with a small group of artists, (the photo above is a gag publicity shot; please disregard the attire.) eight of us, living along the Gulf Coast of Florida. Some are painters (including John and Suzie Seerey-Lester, probably the nation’s preeminent wildlife art couple), some, including me, are photographers. We are four couples who appreciate each other’s art, greatly enjoy each other’s company, and make amiable traveling companions. So off we go, for long weekends or multi-week jaunts – around Florida, up to Maine, out to Wyoming, over to Cumberland Island, Georgia – wherever the spirit and artistic possibilities move us.

At the end of one of these junkets, this to Useppa Island, the Florida isle where the CIA trained Bay of Pigs fighters back in the sixties, we realized that our little band of artists needed a name. Several of us around the dining table in the dignified Barron Collier Inn had surely caught the spirit(s) of the evening but it was one of the teetotalers, of all people, who came up with the idea that since we were a cabal of both PHotographers and ARTISTS we must surely be designated henceforth and forever as The Phartists!

Logo-ed shirts, caps, vests and name cards made official the designation. And we set off on another trip.

It was in the restaurant in terminal C, Logan Airport, Boston, that finally someone had the nerve to come up to us apologetically, “Sorry to bother you, but my friends and I saw the logos on your shirts and caps and just had to know. The name Phartists – one of us thinks that means you’re some kind of artists; one thinks it means you’re just a bunch of Old Pharts.”

�You�re both right,� we confessed.

Enough of that. We were discussing the symbiosis that can be so healthily generated between painters and photographers. Even though, at times the disciplines seem so different. Differences such as:

- Painters like to call themselves artists and the rest of us photographers, the adjective “mere” implied if not intoned. As though ours is not every bit as much an art as theirs.

- Photographers, for their part, note how painters, if they don’t like that tree over there, just “garden” it out. On the other hand, if they want a deer to wander across the meadow they’re painting they wander it there. As one of our photographers noted, “You painters, changing nature to meet your wishes, think you’re God. We photographers, capturing nature’s glories without embellishing them, know who is.

- Painters need time on a scene to commit their plein air paintings. Several hours, probably. Two field paintings a day is good output for painters. Photographers tend to accept Ansel’s dictum that if you wait here for just the right conditions, you’re missing something over there.

- Photoshop notwithstanding, the photographer must take the light as it appears. Hence, the favoring of dawn and sunset light and the need to be up early and work late. John Sexton popularized the term “Quiet Light,” many of his finest images captured in lengthy exposures well after the sun had set. Painters, on the other hand, can backlight, frontlight, or quietlight their work at will, any time of day. They can sleep in.

- Those are some of the procedural differences between the art forms. But we’re here to talk about how the art forms can work together, the practitioners of one learning from colleagues of the other. That’s certainly what happens among The Phartists.

- One of our painters has developed quite a niche depicting old barns. Many of these, she locates for herself. (I’ve got to interpose: One day, spotting a great old barn, she stopped, approached the farmer working outside, introduced herself and said “I’d just love to paint your barn.” To which he replied, “Thanks, but don’t really need paintin’.”) Her paintings show creaky barns perhaps with a flock of doves taking wing from a misshapen, glassless window, perhaps with a barn owl in residence, or a cat spooking swallows.This oeuvre sells well for her so we photographers try to help. Given free time in the country, should one of us come across a picturesque old barn we’ll make a few photographs to provide her additional source material. Even if we don’t have any intention of using the photograph ourselves we’ll do it to help her. She, in turn, may one day steer us to scenes we might have missed for photography. Symbiosis.

- At times, several of us will tackle the same subject. Makes a good exercise in comparative composition. Each of us taking part sees the subject with his own eyes, renders it with his own skills. Studying the results is informative. We are all still learning and will be.

- The photographer, by the etymology of the word, is a “light-writer.” The object of a photograph may be a horse or a waterfall or a group of trees but the subject is always light. Painters need to consider this. You see too many paintings where the artist apparently didn’t know or care where the light was supposed to be coming from. Didn’t bother with highlights, shaded areas, to say nothing of cast shadows. Such painters need to be more aware of light as photographers always have to be.

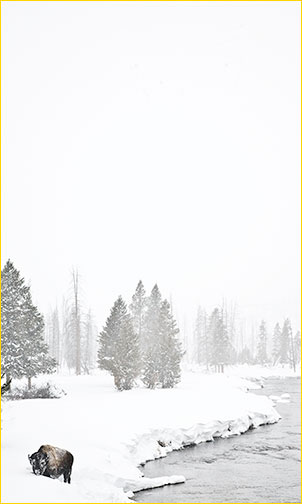

- The most accomplished painter in our group conducts occasional art classes, people from across the country (and abroad) coming to his studio to partake of the wisdom of his experience. One thing he teaches regards composition. Too many artists (and photographic artists as well!) tend to place their principal subject smack in the center of their frame when, in fact, that is usually the weakest positioning possible. There are exceptions of course, when central placement heightens a desired symmetry. But for many, even most, images our friend teaches that the most powerful positioning places the subject in the upper left corner, or upper right, or lower left, or lower right, in that order. I had this in mind in Yellowstone last winter when I came across a lone bison beside a river. I framed the shot so that he was not in the center but powerfully placed hard in the lower left corner, leaving plenty of open space at the top.

- For a photographer, the temptation is great to shoot too quickly. Especially with digital gear, you can shoot quickly so you do. Without taking the time for the forced deliberation large format film cameras required. Here again, the photographer can learn from the painter who is required to spend reflective time on a piece.

- A devoted photographer usually has gear close at hand, some camera, any camera, ready to deploy instantly should cause appear. In this, the painter can learn from the photographer by having a sketch pad or hand held watercolor kit close by. It’s gotten so that one of our painters seems never to stop. On the plane heading toward our next outing, he’s sketching an unknowing man across the aisle in the row ahead. As his wife drives along the highway, he watercolors what he calls ZoomArt on postcard stock that he then mails to friends back home. One of our photographers does the same thing, carrying a small, dedicated postcard printer in his luggage. Works up an image in Lightroom, prints it off to cards. Not necessarily cheaper than store-bought but more to be treasured by the recipient.

- Photographers learn to consider the Near-Far relationship in a scene, to enhance the feeling of depth with a nearby object focused in the foreground, a distant object in the background. We use small f/ stops or shift/tilt lenses to accomplish this.

One of our Phartist photographers, though, expounds another theory of Near/Far. His premise is that an image, to be successful, must be engaging whether one is standing far from it, or up close. How often have you seen a picture on the wall from across the room and it has drawn you forward only to find that up close it let you down? It was badly focused or over-sharpened or simply ill conceived? It happens the other way as well. Up close a photograph may be technically superb, a subject of interest well captured and printed, but step back. From a distance the whole image may dissolve into a framed blur of no distinction, nothing to catch the eye at all. A photograph, to be successful must work from either near or far.

From afar it must have something that, without the detail to be seen later up close, will still capture a viewer. Likely this will be the overall geometry of the elements of the composition. In “March of the Trees,” a photograph taken on a trip with Michael Reichmann across The Palouse, the rolling farmlands of eastern Washington State, the dark, slanting tree shapes and echoing, angled cloudline create the geometry that stands out even at a distance. Moving closer one notes the precision of the trunks and the crop rows and finds himself admiring up close the measured labor of a fastidious farmer. Whether from near or far, the image works. Painters, if not merely illustrating for a book or magazine, but painting for the wall, might keep in mind this importance of Near/Far impact.

- The greatest lesson, though, that both photographer and painter can learn in each other’s company is the mutual joy of creativity. We Phartists go back to our rooms at the end of a day of work and study each other’s output for the day, commenting, discussing, and mutually appreciating. We know that whatever the medium, an artist is blessed to have the privilege each day of seeking the stunning, finding and using his or her skills to share the exquisite beauties that non-artists too often ignore and pass by.

The Phartists will be hosting a summer exhibition and sale of their various works at the prestigiousVenice Art Center, Venice, Florida,

starting with an opening night reception June 27 th and continuing until August 15 th . If you’re in the area, please stop by.

June, 2008

___________________________________________________________________

Jack Perkins spent a career in television: corespondent for NBC News, host of “Biography” on A&E.

Retiring with his wife to first Maine then Florida, he began working in both photography and poetry,

combining those art forms to produce two books: Acadia: Visions and Verse” , and “Island Prayers: Photographs and Poems of Praise.”

His wife, a painter, illustrated two bird guides, and now sells oils and acrylics, most of birds.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

You May Also Enjoy...

Ghosts Among The Aspens

FacebookTweet When we think of the Canadian Rockies the usual image is of sweeping vistas with snow capped peaks lining valleys with turquoise rivers and