By Juan Oliver, Efraín García, Javier Martín, Cristina Alonso and Rubén Osuna

This article deals with the possibilities of Photography as an artistic medium, a subject presented by Michael Reichmann in his article Learning the Language of our Art. We don’t pretend to have the only valid response to questions about the language of Photography, we are more interested in presenting a starting point to think about, and bring all of you a set of points of reference.

Photography has two mixed natures, similarly to other framing Arts, and the first section is devoted to its artistic and documental dimension. We will use Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, the famous movie about Photograph –and many other things–, as an example for our reasoning. The presence of the cinema will not end here.

The second section deals with the expressive possibilities of Photography, and we have been inspired by the bookTheory of Film Practice, by Noël Burch. Many of Mr. Burch’s findings have nothing to do with Photography, but many ideas belong to the realm of the framing arts. We will connect Burch’s analysis and Photography using a picture by Garry Winogrand that belongs to the set of pictures taken during the Guggenheim grant that allowed him to travel throughout the United States in 1964. Many of these pictures have been showed in exhibitions and printed in books, and we have found our example in the rare and delightful book “Winogrand 1964” (Arena Editions, 2002). Garry Winogrand applied the basic rules of composition and expressivity explained by Burch and condensed in this section by us.

We want to stress the interconnection among framing arts. In order to do that, we will connect Winogrand’s photograph to a famous painting of the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez:Las Meninas. It is very impressive to walk through the decagonal hall at theEl Prado Museum in Madrid, and see that big and complex painting, at the centre of the hall, leading to the main gallery. Both, the photography and the painting, are two good examples of a full exploitation of the expressive possibilities of the framing arts (cinema only adds time to the equation).

Antonioni’s Blow-Up, any of Winogrand’s books and Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice are obvious recommendations to every photographer interested in the practice, theory or even ontology of Photography. The main argument is that Photography has a set of expressive possibilities and this determines its value as a medium for artistic expression, unstructured but constrained. The documental value of Photography has been (and is) overstated.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Photography and Reality

We know that behind every image revealed there is another image more faithful to reality, and in the back of that image there is another, and yet another behind the last one, and so on, up to the true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that no one will ever see.

Michelangelo Antonioni

Any picture made by a security camera or a webcam may have a great documental value, specially if a criminal is recognizably “portrayed”. However, those pictures have no artistic value. The documental value of a photograph is not a sufficient condition for an artistically valuable photograph, or even a necessary one. You can get artistically interesting pictures with no documental value at all as, for instance, abstract pictures.

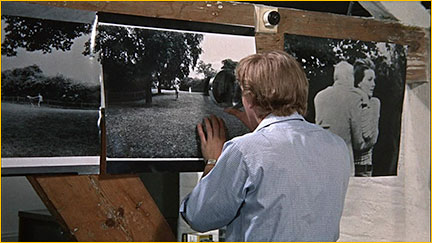

Thomas (David Hemmings) takes pictures in a park

Antonioni’s Blow-Up(1966) (cinematography: Carlo di Palma) deals with the impossibility of grasping the reality by any means, including Photography. The quoted phrase above comes from a book written by Antonioni, and is used in his filmBeyond the Clouds(1995), capturing very well the essence of many of Antonioni’s obsessions. InBlow-Up, a photographer (inspired in David Bailey, a real photographer and a star of the swinging London of the sixties; we strongly recommend his bookThe Birth of the Cool) takes a series of pictures in a park by chance (a couple playing around). The entire sequence is beautiful, with magic frames and elegant movements of the camera, typical of the exquisite photographic taste of Antonioni. The park (Maryon Park in London) was painted with green because Antonioni wanted to stress the eerie ambience of this sequence. The girl photographed realizes that a photographer is shooting there, and runs alarmed towards him, asking for the roll of negatives. The photographer becomes intrigued by her reaction and decides to take a closer look to the photographs.

There is something in this photograph, but we cannot see it

In each blow up and ordering of the series of pictures (more on this later), Thomas discovers new layers of reality, like in an archaeological excavation. A plot slowly emerges, growing and becoming more and more complex, but up to a limit. Enlarging too much causes the negative to become an abstract painting –like the works of Bill, Thomas’s neighbour who is a painter. As a result, the documental component of any photography (or painting) disappears. It doesn’t have consequences for Bill, the abstract painter, but it is a tragedy for Thomas in the particular circumstances of his investigation. We approach Art when the reality escapes untouched. At the beginning of the movie Thomas was trying to make artistic black and white photographs narrowly connected to reality, documenting the life of homeless people. The movie ends when Thomas realizes why he was unable to understand Art, and particularly, Photography as an Art. The plot was a liberation and awareness process for him. Truth, like art, is in the eye of the beholder.

Successive blow-ups bring out deeper layers of reality, but is it all the relevant reality?

We are only able to see the surface of things, and Photography (or Cinema, or any other form of framing art) is not about reality or about testimonies of that reality. Many famous photographers’ works are appreciated by their documental value. Lets consider Walker Evans, for instance. He had a vast influence in the following generation of photographers and his work about the consequences of the Great Depression in rural areas of America is a key work of the past century. Sebastião Salgado is another good (and contemporary) example. We discuss if their work is true artwork, independently of its documental value. We don’t mind if those pictures have or had a value or relevance as historical documents. The artistic value must stand for itself. What is photographed, or when and how, is of no relevance for the final artistic result. A true historical event is not a better photograph from an artistic point of view than a simulated or prepared scene. A revealed fake can destroy the value of a photograph as a document or testimony of the reality, but not as an artistic work. Art is a non-structured medium that allows the expression of things that cannot be transmitted by regular means.

Photography has a basic essential restriction: you are forced to take an image from the visible (first, superficial, random, ever moving, full of “decisive moments”) layer of reality (though you can control some of this in studio). Painting is different. You can translate anything from your imagination to the canvas, after a reflection period, if your technical abilities allow you to do so. And you can correct and retouch.

Photography needs to record something in front of the lens, actually taking place. It is not painting with light, as is usually said, but reading (and recording) the light. This difference does not affect the artistic possibilities of Photography as an expressive medium, as we will see in the next section, just the contrary!

___________________________________________________________________________________

Photography as one of the Framing Arts

Photography is not about the thing photographed. It is about how that thing looks photographed.

A photograph is the illusion of a literal description of how the camera saw a piece of time and space.

Garry Winogrand

There are simple rules for framing based on proportions, distances and so on. You know though that rules are set to be broken. This has occurred in Art once and once again. Think on Music, for instance. There are periods involved in the construction of a set of rules, and its generalization, and subsequent long periods in which its dissolution is exploited artistically. When the Post-romantic period, at the end of the XIX century and beginning of the XX, exhausted the possibilities of the previous rules and its exceptions, a new set of coordinates were needed, and the dodecaphonic and serial music appeared. In some sense, the history of Art is the result of the quest for freedom, a Hegelianiconoclastic process that breaks the previous rules and pushes the limits a bit further. Look at the visual Arts. In Painting, the impressionism was the liberation from photographic realism, fauvism was the liberation from realism of colours, symbolism and surrealism the liberation from the conventional meaning of things,cubism the liberation from realism of forms, and abstraction was the liberation from them all. The immediacy and affordability of Photography makes it even more suitable than Painting for an unconstrained artistic evolution and free experimentation. However, Photography, surprisingly, is yet narrowly linked to realism, to documentation.

We are not saying that all photographs must be abstract, but abstraction should be incorporated to the language of Photography in a more natural way (the quite recent interest in the expressive importance of bokeh or the increasing abstraction of landscape photographs are good examples of this).

We don’t believe in rules when Art is involved. If you need to break some rules, break them. Regrettably, there are constraints that cannot be broken and determine the expressive possibilities of a form of Art. Painting, Cinema and Photography, three framing forms of Art, share many of them.

Fashion, Landscape or Portrait Photography also can make use of those expressive possibilities. Our example, however, will be one that belongs to the genre of Street Photography (or “Animals Photography”, as Winogrand preferred to call it). It is not due to its documental value, as it should be clear, but due to the full use of those expressive possibilities that are theoretically possible when doing that kind of pictures.

Las Meninas, by Diego Velázquez

Now consider Las Meninas, painted by Velázquez in 1656. It cannot be considered a classic “group portrait”. It is more like an “animals photograph”, like a casual shot. It doesn’t matter if this scene really occurred or not. Velázquez was a wonderful painter armed with a superb technique, able to paint even the air, the atmosphere of a scene, butLas Meninas isn’t only a technical exhibition of a master.

The frame can capture relations occurring inside it. But that is not the end of the story, as Noël Burch explained. The world surrounding the frame can be brought into the frame, and we can know things about it just looking at the frame. There is a simple example of it: think on a person looking to the photographer in a portrait. When we see the picture we feel the portrayed person is looking at us, outside the photograph. In this way, the photograph is linked to the real world. It is not an isolated artistic object any more. The same occurs with that part of the world below the frame, over it, at the right, and the left or behind the scene. Temporal associations can be included in a photograph as well. We can connect the moment in which the photograph is taken with some event of the past or of the future. It is usual to see the consequences of past events in the present scene in many photographs. It is difficult to use those possibilities at full with an artistic intention though. This is the natural field of Cinema. However, photographs with this kind of suggestive power are more attractive for the mind.

Lets return now to Las Meninas. The actual size of the painting is 3,18 x 2,76 meters (more like a 4:3 format than a 3:2 format, whereas the golden ratio is 3.2:2). Velázquez himself is included in the painting, looking at us, connecting us to the scene, bringing us to it. He also included other spectators placed outside of the scene, just in the place in which we are! In the centre of the scene we can see a mirror, and a couple reflected on it is looking at the scene. They seem to be the King Felipe IV and his wife, the Queen Mariana de Austria. They are not in our world, they are in Velázquez’s world (place, time), in front (and outside) of the scene, interacting with it (looking at it) from the place (and perspective) in which we are. We also can see a figure in a door (don José Nieto de Velázquez, quartemaster of the Queen. Is he leaving or coming?). He is looking to the scene from the back, and he is out of focus! The door connects the hall (probably in the Alcázar of Madrid, now disappeared and replaced by the actual Royal Palace, built in the XVIII century) with the exterior, where the sun shines, bringing light to the darker interior. All this conform the accessory elements of the painting. The central characters are interacting among them at the centre, in the foreground. The Infanta Margarita is just in the middle, accompanied by “Las Meninas” or “Escorts” (Isabel Velasco and Agustina Sarmiento), two dwarfs (María Bárbola and Nicolás Pertusato, playing with a dog) and behind them two more people (Marcela de Ulloa and an unidentified gentleman). You can see many relationships here, inside the frame and among the characters, outside the frame, behind and in front. This masterwork by Velázquez is a complex “shot” in which the frame is transcended. The beauty of the painting is not in the proportions, symmetry, balance, pleasing combination of colours or subjective impact it produces in the observer. We think it is fascinating due to its complexity and full use of the expressive possibilities of the frame for suggesting us relations, connections, symbols, randomness, time and space. This painting stimulates the intellect, not the senses.

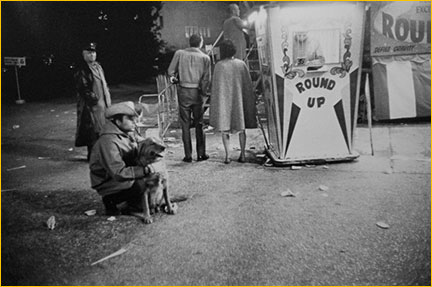

Winogrand at his best: a photograph from “Winogrand 1964”(p. 259)

The best photographs also have this quality. Winogrand has several good examples, but we found one particularly good. It belongs to the set of photographs taken by Winogrand in the United States in 1964, thanks to a grant awarded by the Guggenheim Foundation to him. We are lucky owners of a copy of the rare book “Winogrand 1964”, which includes a selection of the thousands of photographs taken by Winogrand during this project, many of them in colour. The Picture number 5 shows a Velázquez-like use of the space and time by Winogrand, inside and outside of the frame. We can see a man and a woman looking to something outside the frame, to the backstage. A policeman looks to another man that is himself looking to something, also outside the frame, to the right. We don’t know if there is a connection between these characters, or what are they looking at and why. We can intuit seeds of future actions in this photograph, but we cannot be sure about them. Something is happening behind the scene and at the right, and the characters of the photograph are looking to these events. The behaviour or relations between the characters could change due to those events, but we have only one shot. We cannot know for sure if this image shows an equilibrium or not, and we remain intrigued.

Then, we can have an entire series of photographs. The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset explained what adialectical series is with a simple and ingenious example (in hisEpilogue to theHistory of Philosophy, by Julián Marías). When you look at an orange you see a circle, not a sphere. In order to grasp the idea of sphere we must rotate the orange and keep seeing circles. This succession of circles brings to us the idea of a sphere. In the same way, a series of photographs may be necessary for the communication of an idea, a mood or anything else only transferable by means of Art (Do you remember the mysterious series of pictures in Antonioni’s Blow Up?). The photographs pertaining a series are naturally interconnected, but not in a linear way (a succession), as is the case of cinema. The nature of the connection is free of the basic rules that limit the cinematographic language. On the other hand, each picture must stand for itself (and this is not necessarily true for each frame of a cinematographic sequence). Whether we build a series of pictures, each picture in the series will reinforce the meaning of the others, like an isolated circle sustains the idea of sphere. Sometimes, however, a circle is only a circle, and a succession of circles won’t bring any supplementary idea.

Winogrand is known as an intuitive photographer. He didn’t elaborate a complete theory about Photography. Winogr and preferred to take picture s following an impulse (he was aware of the randomness of the world), and then select them in a separate stage (leaving a period of time in between). The “decisive moment” in front of the lens doesn’t make a photograph interesting from an artistic point of view[1]. Even more, Winogrand made “decisive” any momentafterthe photograph was taken, just selecting it for printing. In the selection process, Winogrand sometimes applied pure aesthetic principles, but usually also some measure of expressivity based on complexity and intellectual stimulation. He made many “beautiful” photographs, but also many suggestive photographs that go beyond beauty.

Photography, Painting or even Cinema, have a limited capability of saying anything meaningful about reality. Their value as artistic mediums isn’t in their descriptive or prospective capabilities. Particularly, the documental value of a photograph doesn’t add or reduce its artistic value. Most professionals, however, depend on the documental capabilities of their cameras, and many technical reviews of cameras and lenses stress how well the equipment records the reality (this is the basis of the misunderstanding and underestimation of less than perfect cameras and lenses). Even more, it is supposed that magazines and journals sell information about reality, with some photographic support as a testimony (this, of course, is untrue, and Photoshop isn’t the only cause). It is easier to extract some clear “meaning” from a documental photography than from an artistic photography. The artistic value of a photograph is more difficult to appreciate.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Efraín García,Juan Oliver,Javier Martín and Cristina Alonso are professional photographers. Rubén Osuna is University Professor at the UNED, Madrid

[1]Portraits are a difficult kind of Photography, just because it has limited possibilities for variability. This explains the feeling of “deja vu” of many good portraits. Henri Cartier-Bresson developed a particular method that gives more play to randomness (those marvellous interview-portraits). He was looking for a “decisive moment” to record, getting more variation in the sample, and more possibilities for a later choice. Of course, you could get the same result just making the portrayed person to pose in an adequate way. This would imply thinking the photograph before it is taken, like in a painting. A good example of this would be the work of Arnold Newmang.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

You May Also Enjoy...

Panasonic GH1 Video Hack

Year OneAbout a year ago, in July, 2009, Ireviewed the Panasonic GH1's video capabilitieson these pages, and in the months since have used it as