After a while one tires of pretty pictures. At some point a theme, story, and organizing principle is required to impose discipline and focus one’s attention. I noticed that my photography usually improves markedly when I have an object in mind. Thus far most of my projects have resulted in books, but the same precepts apply for upcoming exhibitions or covering a friend’s wedding. They all require vision, anticipating the elements that will be required, a plan for execution, the actual photography, and unblinking editing process, and all the elements to bring forth the finished product.

Each project seems to give birth to itself. I feel drawn toward a subject. As I look at the object of my interest, I try to uncover what attracted me in the first place and highlight those aspects in my work.

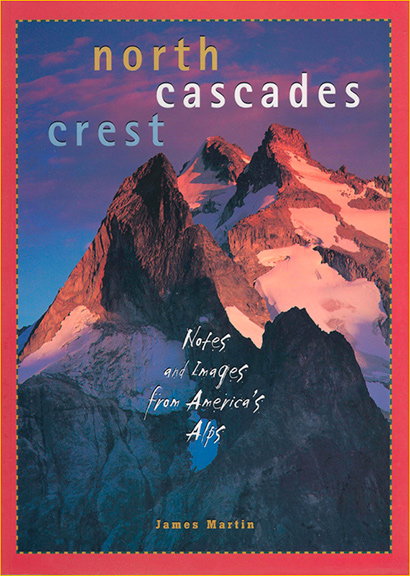

North Cascades Crest. Pentax 6×7

My first photography book,North Cascades Crest(Sasquatch), emerged from a confluence of influences and experience. I had hiked and climbed throughout the range, favoring the wildest and most remote ridges and peaks. Years before I made my way to Washington State, I poured over images in North Cascades (Mountaineers), black and white photographs by Tom Miller. Printed in 1964, it sought to justify the creation of the proposed North Cascades National Park, eventually established in 1968. Miller had ventured across glaciers and through near-impenetrable brush to capture photographs of the wildest mountains in the lower 48.

Initially, I wanted to create a color version of Miller’s book, but as I considered it, I realized that every aspect of my treatment should reflect particular passions that animated me toward pursuing the project in the first place. I decided to write it myself, to indulge my interests, obsessions while trying to convey how I felt about this remnant of wild America.

I started my shot list, a set of pre-visualizations. I wanted each image to be a knockout so I opted for medium format, starting with a Pentax 6×7 and burly Gitzo. I was pretty sure no one had canvassed the high country with higher resolution gear. In short, I tried to differentiate my work while being true to my vision.

The northernmost extent of the Cascades crest seen from the summit of Whatcom Peak.

Pentax 645

For the better part of a decade I trudged into the mountains hoping the weather would clear when I needed it. Sometimes I got skunked but more often I was rewarded. Carrying a full backpack, the Pentax kit, and climbing gear, I paid for each shot in sweat, but I loved every minute, at least in retrospect. In the end, I was content with the book.

Each subsequent book followed the same sequence.

Visualize

What story do you want to tell? How does the project cohere visually and thematically?

Photographers frequently tell me they want to produce a book. When I ask about the focus of the book and why it would interest a stranger, most have no idea. Unless you’re an Edward Weston, no one will be interested in the published equivalent of a photo album.

Ansel Adams, while an artist first, created his iconic books as vehicles to promote wilderness preservation. Cartier-Bresson valued the decisive moments. Even photography anarchists, scions of the Abstract Expressionists and their descendents, adhere to a vision. All had something to say and marshaled the power of their art, the convergence of technique, composition, and magic, to communicate with the world.

Clarity of intent makes all the difference.

Differentiate

“Think Different” advised the Apple marketing department. Ignoring the grammatical infelicity, I see it as a two word artistic manifesto.

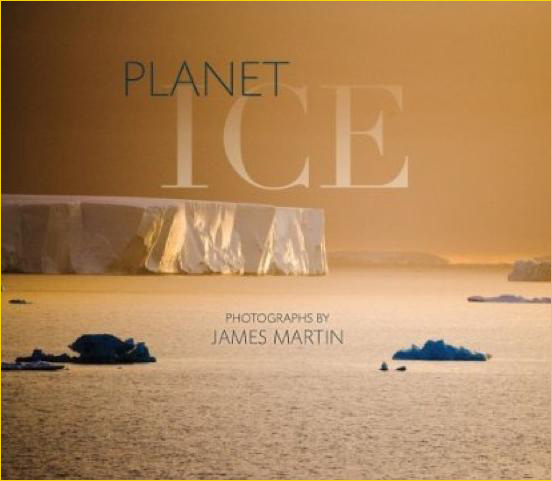

Planet Ice

When I decided to embark on a book project concerning the vital role and astonishing beauty of ice on Earth, I needed to find a way to tell the story my way. I was offered the chance to publish it with the Alaska cruise market in mind, essentially a collection of pretty pictures, but found that scope was far too constricted.

I resolved to shoot worldwide, to present a global view from a single perspective. So far as I knew, no one had done that. Although I had read widely on how ice shapes landscape, affects wildlife and people, how ice impacts climate as climate changes its extent, I was no expert so I solicited a top climatologist, geophysicist, biologist, poet, and climber to contribute to the text. Again, this was a new approach. In 2009 Braided River publishedPlanet Ice.

We remember the photographers and projects with something new to say. I have no idea how Nick Brandt came to shoot African wildlife with short focal length lenses, in monochrome, often with a pronounced vignette, but it’s both dramatic and was once unique before a gaggle of mimics caught on. Balog’s studio portraits of wild animals gave us a new view of them. Examples abound.

There is a marketing component as well. Gallery owners and publishers do not value “me too” work. Set off on your own. Imitation is like practicing your scales. Even Picasso copied the masters, at least when he was in short pants. When you’re ready to offer your vision of the world and art, at least make it your own.

Plan

You have a vision, the look, the subject, the differentiating elements. Now it’s time to figure out how to translate vision into something palpable.

Create a shotlist with as much specificity as possible. This is the time to put your imagination in charge. Don’t worry about being confined by the list. Over time opportunities will present themselves.

Not every list needs words. In 1990 Art Wolfe and I went to Africa on assignment for Smithsonian. (Those were the days…) He kept a notebook of sketches, compositions he intended to capture on the trip. I was skeptical, but day after day he got the photograph he’d envisioned. It was as if nature was cooperating with him, but in fact, he was preparing his mind to recognize when the elements he had visualized were coming together. He would ask the driver to move forward ten feet, back five and so on until foreground, subject, and background was arranged to his satisfaction. Since I draw at a third grade level, I write descriptions occasionally enhanced with stick figures, but it works for me, triggering the memory of what I’d imagined days or months earlier.

The logistics of a large project can be daunting. Planet Ice required travel to Antartica and the northern tip of Greenland, to Iceland and the Alps, hikes to Everest Base Camp and across the Mountains of the Moon, an ascent of Kilmanjaro and forays into the Andes from Ecuador to Patagonia. I returned to the Cascades, Canadian Rockies and Alaska Range. The publishers and I worked with our all-star team of writers and shepherded the book to print. I gave myself two years to shoot it and a year to bring it to publication.

Planning became a juggling act, a multi-variable game of three dimensional chess. The shot-list was set, the locales determined. I had to get myself to each site at the right time, to adapt my equipment to the environment, schedule according to my physical capacities, arrange for guides or porters when needed, and pare things down when I had to travel solo in rough terrain. Visa and immunizations were secured.

First I looked for free help or a paying gig to get me on site. Some research scientists gave me a free ride to the Greenland Ice sheet while Joe Van Os Photosafaris added me as a trip leader to Antarctica and South Georgia. Clustering destinations saved time and money. After hiking the Ruwenzori range in Uganda, I hustled up and down Kilimanjaro in 95 hours. Iceland and the Alps fit in another trip. Between trips, I persuaded the writers to commit while working with the publisher. I met the deadline, but some of my plans didn’t work out. Politics kept me out of Tibet while diminishing funds precluded a late season shoot on the North Slope. Overreach and you end up with more than you can reasonably expect.

Shoot

This was the fun part. Often I found the composition of my dreams. Other times were blessed by serendipity. I had hoped to shoot a dense, unbroken pattern composed of king penguins on South Georgia and both conditions and penguins cooperated. I imagined a procession of icebergs in the Greenland fjords and again nature provided.

Inside an ice tunnel at midnight on the bed of a drained surface lake on the Greenland Icesheet

Other times I was taken aback by what was in front of my lens. After setting up camp on the Greenland Ice sheet, the group of geologists and geophysicists decided to check out a meltwater surface lake that had drained rapidly when a crevasse opened. We found oddly shaped chunks of ice on the lake bed. The water rushing into the crevasse had bored tunnels through the ice. I spent hours shooting the blue ice as the sun skimmed just under the horizon. I don’t think this subject had been shot before. It certainly hadn’t made it to my shot list.

Throughout shooting, I clicked through my shotlist as best I could and seized the unexpected. Just showing up provided me with opportunities. I didn’t get everything I wanted, but I encountered more than I had expected.

Edit

“Kill your darlings” advised the editor of an article I wrote. He meant that any phrase that doesn’t contribute to advancing the story, especially one so clever it calls attention to itself, must go.

The same is true in a project. An incongruous image, especially a striking one, shouldn’t become part of the project. It interrupts the flow of the book or exhibit. It’s better to include a lesser image that fits. Better yet, cull everything that isn’t excellent or vital.

Production

What, if any, compromises are you ready to accept? If the answer is “none,” life is easy, possibly made easier by the likelihood your project will never see the light of day absent significant personal resources. Potential collaborators rarely put up with the intransigence. It’s also true that fanatics produce the most amazing work. It falls to you to assess the balance between ultimate quality and completing the project at all. For many, creating the images more than suffices. Know who you are or who you want to be and proceed as your authentic self.

My experience is not universal, but I’ve seen other successful photographers follow the same sequence. Try shooting with a project in mind to elevate your photography to the next level.

October 2011

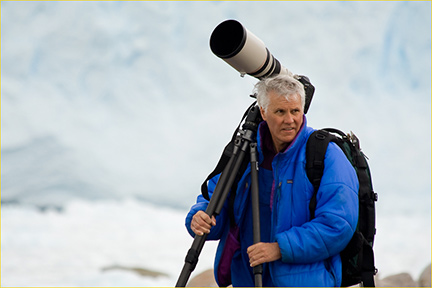

James Martin

James Martin has produced 20 books and numerous articles. He will lead a tour to Burma and Cambodia this November for Joseph Van Os Photo Safaris (www.photosafaris com) where participants can shoot medium format and offers project-based trips limited to four participants in India and Madagascar (www.jamesbmartin.com).