When is good enough not good enough?

By: Richard Lohmann

The Getty Museum faced a dilemma. They had to decide if they were going to purchase a 6th-century B.C. Greek sculpture called a Kouros for their permanent collection. For 14 months experts inspected, examined and tested everything measurable about this classical treasure to determine it’s authenticity. Science could not find any evidence that it was a fake. In his bookBlink, Malcolm Gladwell describes the dilemma.

Blinkis about rapid cognition –– about the kind of thinking that happens in a blink of an eye. As the story unfolds and after the Getty purchased the piece, an art historian instantly knew that it was a forgery. His technique is to note his first thought, with every first-glance of art. When viewing the Kouros his first thought was “fresh.” Only later did he know why the Kouros was not authentic. But in that first moment of viewing, at a level below conscious awareness, he knew that the Kouros didn’t have the look of marble that had been buried for centuries.

My “Blink” experience relates to the new ink-jet papers that use rag or alpha cellulose paper, and have glossy surfaces inspired by the look and feel of traditional, fiber-base gelatin silver photographs. Starting as a platinum printer in 1977, I have long preferred cotton rag papers because of their inherent elegance. In my own work I am very content printing on Rag paper using hand-blended carbon inks. But there are many people who prefer prints made on glossy papers. I am eager to see glossy ink-jet papers move away from the look of resin-coated papers because the currently available plastic ink-jet papers lack the beauty of traditional photographic prints.

In 1979 I saw a print that Don Worth made on Kodak Ektacolor paper manufactured in the 1960’s. Stored in darkness, its colors were pure and delicate. At the time, what struck me about this print was that it was made on a gelatin-coated fiberbase paper. It was extraordinarily beautiful, especially when compared to the resin-coated papers that had already been established, and are still the norm in today’s color darkrooms.

I remembered this print when I learned that several manufacturers were releasing new ink-jet papers designed to replicate the look of gelatin-coated papers. I thought that if there were going to be an abundance of elegant papers available in the digital world, then more photographers would choose to work digitally. Given the choice between a piece of plastic or fiberbase print with a gelatin-like surface, I know which direction I would go.

Teaching critical evaluation, especially in digital photography, is vital. Many students become quite proficient with Photoshop using Curves and Levels to manipulate their images, but often don’t know what to do with those controls because they don’t yet understand the potential of the medium. One of my biggest responsibilities is to teach them about quality, and to help them develop a refined photographic sensibility.

With this in mind, I recently tried three of the new ink-jet papers: Crane Museo Silver Rag, Hahnemuhle Fine Art Pearl and Innova FibaPrint Gloss.

The first paper I tested was Crane Silver Rag paper. Several reviews of this paper were glowing. Reviewers hadn’t said much about the surface of the Silver Rag, except that the paper looked strange before printing. One reviewer noted that the surface texture was smooth. When I carefully examined my test print, I discovered Silver Rag’s surface has an uneven sheen that could only be described asÅ“scratchy". Despite its lovely image tonality and deep blacks, I couldn’t ignore the surface of the paper.

I have always admired prints that have apassivesurface that lets the viewer look deeply into the print. And while such prints may possess gorgeous texture, tone, color, and depth, these qualities should "fly under the radar" and not immediately call attention to their role in the beauty of the print. Silver Rag is just the opposite––it has anactivesurface that diverts attention away from the experience of the image itself.

Those who find Silver Rag’s surface less objectionable have said that the texture will likely disappear once the print is framed. At a recent photography exhibit I was able to put this theory to the test. At the behest of the photographer, I was able to identify a framed Silver Rag print, hung next to some gelatin silver prints. The photographer was hoping that it would blend in. So much for the idea that the surface is hidden when framed under glass. At Photo San Francisco, I recognized a print made on Silver Rag paper wrapped in a plastic bag sitting in a gallery bin. The surface is that noticeable.

Part of the problem may be related to the kind of lights used to inspect finished prints. It’s important to note that some photographers evaluate their prints using viewing booths that are designed for color accuracy, although that accuracy has been debated. Color temperature aside, I believe florescent light viewing booths may create a bigger problem. The florescent light produces a soft diffused light that masks the problem of textured print surfaces. Silver Rag tends to scatter light, and when scrutinized in a viewing booth or other type of diffused light, its surface may look acceptable. But under directional light and gallery conditions this paper suffers.

The type of viewing light can dramatically affect your perception of the paper’s surface, but also can change how you see the tones within the print. Recently I made one print on rag paper that has a D-max of 1.76, and then printed the same image on glossy paper that had a D-Max of 2.22. They both were viewed in soft diffused light, and much to my surprise the prints looked quite similar. But when viewed in more collimated halogen light, the gloss print had a much different appearance. The deeper blacks were more noticeable and lower values of the glossy print were crisper. This taught me how important viewing lights can be, and how they can either mask or enhance the characteristics of a print. I believe that the variety of reactions to Silver Rag may be due to the viewing conditions in which the prints were evaluated.

Before testing the other papers, I considered Silver Rag an incremental improvement with its good image tonality and deep blacks on rag paper, but its surface still makes it an unacceptable choice. When judged not as an incremental improvement, which seems to be the mindset of many, but as compared to traditional materials, Silver Rag is in fact an ugly paper. If a paper with its surface had been released as a traditional material, I believe that it would have been criticized by reviewers and then ignored by discerning photographers.

My next experience was with HahnemuhleFine Art Pearlpaper. This paper has a less noticeable texture than Silver Rag. Its surface reminds me of Agfa Brovira 119, a paper that was once quite popular in the 1970’s. The paper has a less active surface–– but not a smooth glossy one. Like Silver Rag, the Fine Art Pearl has good image tone, and blacks comparable to the best gelatin silver papers. The surface is acceptable because it does not attract undue attention to itself. When compared to Silver Rag and the new FibaPrint Gloss, which both have noticeably unpleasant surfaces, Fine Art Pearl appears closest to traditional photographic materials. I hope that Hahnemuhle will create another paper that is smoother than Fine Art Pearl, a paper that has a surface like Ilford Gallerie or Multigrade, and would give digital workers the surface we have been requesting for over a decade.

Having tested two papers, with Fine Art Pearl a huge improvement over Silver Rag, I was expecting a lot from FibaPrint. Their website says:‚ Innova FibaPrint has been modelled on the traditional fibre-based gloss material used in conventional photography¦

When my package arrived I quickly loaded a sheet into an Epson 4800 printer. When I viewed the image made on FibaPrint paper, I had a “Blink” moment––the very first thought that popped into my head was, well, Naugahyde. The print looked as if it had been printed on white Naugahyde vinyl. Its surface and texture reminded me of seats from the family car of my youth –– a 1970 Oldsmobile VistaCruser station wagon.

Perhaps this sounds funny, but I was not amused. I was angry. I’m still angry. This paper looks nothing like traditional fiber-based gloss materials used in conventional photography, and anyone who says it does has forgotten what a traditional print looks like.

Why are we being told that these papers are elegant new products, when they are clearly not? Are the engineers who create these products simply unaware of what a fine print looks like? Have they carefully examined the surface of a fine print?

The digital community needs to demand better papers before it is too late. Photographers have been too accepting of what the digital industry manufacturers have offered. It’s time to require better and more elegant products.

I spoke with David R. Williams, Sales and Marketing Manager at Crane, the company that manufactures Museo Silver Rag. Mr. Williams has a background in the traditional photographic paper industry. He said that Crane had intended to recreate the look of a traditional paper, but that digital materials are in fact a different technology using different materials. Recreating the look of gelatin-coated paper can be done, but other factors, such as eliminating gloss differential and creating deep blacks were also considered when creating Silver Rag.

In June I taught a digital black and white printing workshop for the Ansel Adams gallery. While inspecting prints made on Silver Rag paper, at arms length were framed Adams prints. When I looked at the prints side by side, the difference between the materials was stunning. Then, I realized how disappointed I was with Silver Rag paper. And I remembered the quote on the Crane website: “Announcing: The Death of the Darkroom.”

Mr. Williams said that the paper is selling very well and that people love it. He said that during the test period, of the 131 users, only one person said that they wouldn’t use it. He explained that most people got used to the paper’s surface and he characterized Silver Rag as a “great success”.

But is it really? By what and whose measure of success? Presently most digital workers either ignore or overlook the problems with these new papers. They are glad to get something they consider an improvement over the plastic papers. But I have heard little critical analysis from digital photographers. When I show prints to accomplished photographers not working digitally, they can’t believe that FibaPrint and Silver Rag are in any way considered equivalent to traditional materials.

In the bookThe Universal Traveler, Don Koberg coined the term “constructive discontent.” His book on creativity and problem solving teaches people to always look for creative solutions. But he wisely notes that you can’t find solutions until you identify the problem.

It’s as if the digital imaging community has developed amnesia. Each new product is being judged only in terms of its immediate predecessor. Yes, Silver Rag looks better that Epson Premium SemiGloss. But have we forgotten what came before the digital avalanche? Look,really lookat the tonality, surface and luminance of prints made by Paul Caponigro, Fredrick Sommer, Edward Weston or John Sexton. At some point the digital community needs to remember what the masterpieces of our medium look like, and should remind itself of what true quality looks like, as a baseline for comparison.

Innova’s website tells us that FibaPrint was modeled on traditional materials, but when compared to gelatin silver papers, the look and feel of FibaPrint Gloss screams of bad taste. We want silk and we’re getting polyester. FibaPrint has a fake glossiness owing to its plastic-like pebbled surface. I don’t like the paper, or the manner in which the product is being marketed and sold.

Like the Kouros, will we allow ourselves to be like the Getty and buy into the manufacturers’ technical and marketing hype instead of relying on our own critical evaluations?

Unless someone speaks out, and digital photographers embrace the concept of constructive discontent, papers like FibaPrint Gloss may become the norm. Conversely, manufacturers need to do a better job working with a larger segment of the photographic community, reaching out to more than the usual suspects for product feedback.

A friend has been predicting that in time, once the traditional materials are gone, people will simply accept what is available. Most won’t know the difference between inferior printing materials and traditional prints that have come to define excellence as we now know it.

I don’t want to let inferior materials become the new look of photography. FibaPrint and Silver Rag papers are not good enough. Unless paper quality improves, someday soon we may find that the age of traditional photography will have passed, and we are left to print on papers that look like white Naugahyde vinyl.

© 2006 Richard Lohmann

______________________________________________________________________________

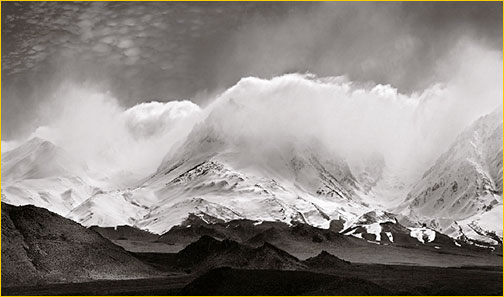

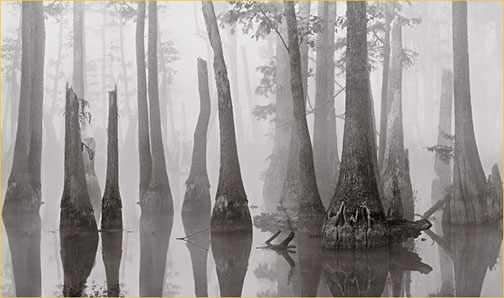

Richard Lohmann earned his B.A. and M.A. in Photography from San Francisco State University. He has successfully transitioned from 26 years of platinum printing to making digital prints using hand-blended carbon inks on paper. He is currently producing a body of work titledAtmosphere, where he is working with visual metaphor. He and Tom Mallonee teach a workshop titledInk on Paper – A Guide to Digital Black & White Printmakingfor the Ansel Adams Gallery.He is currently a professor of Photography at College of San Mateo.

His images have been exhibited at the Photographers Gallery in Palo Alto, The Saret Gallery in Sonoma, The Edward Carter Galleries in Gualala, The Alinder Gallery in Delaware, The Platinum Gallery in Santa Fe, Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica, and Modern Book in Palo Alto