By Kathleen Hay

One of the world’s oldest photographic portraits is that of Philadelphian metallurgist and chemist, Robert Cornelius – taken byRobert Cornelius. The silver plate image, captured in 1839 on the heels of Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s invention of photography, is the first ever Daguerreotype self-portrait, and is one of the first documented photographs of a human being.

Though Cornelius’ photographic endeavors were not that of an artist, but of a professional studio portraitist, his self-portrait heralded a revolutionary era of artistic expression. However, the genre of self-portraiture is as old as the first renderings on cave walls, preceding Daguerre’s invention by centuries.

It was the fifteenth century period of the Renaissance that witnessed an increasing prevalence of the self-portrait – an abundant subject demonstrative of many artists’ paintings and drawings of the time through their seemingly innate curiosity to explore themselves, as much as new facets and aspects of their medium.

Throughout all the ages of art, narcissism has played out to varying degrees. Whether innocent curiosity, sheer playfulness, or a developed inquiry into self – aesthetically, spiritually or otherwise, the reflection of one’s own image has played catalyst to a great many deeper explorations, and yes, even deeper obsessions, and has, as a genre unto itself, manifested some of the most fascinating art, in all its various forms.

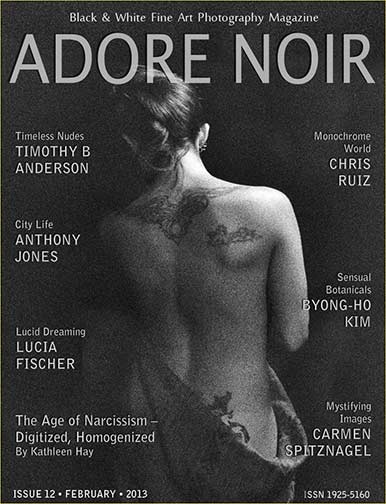

This centuries old curiosity has, in the span of two recent years, mutated into a creative juggernaut. With the new millennium celebrity and social media obsession detonating an age of narcissism, artistic endeavor is being homogenized via the most enabling, vastly accessible and photographically simulated landscape that is social media giant: Instagram – square format, sixteen filters, and all.

From Daguerreotype to Instagram, the mammoth technological shifts in photography towards the digital mass-market camera-phone snapshot has not only roused young users into a ‘me’ epidemic, it has levelled the medium’s creative gravitas – wringing it from its ancestral roots and leaving to the archival world a cultural wasteland of digitally filtered ‘selfies’.

With over eighty million users and counting since its inception in 2010, and recent acquisition by Facebook, Instagram has been satiating the narcissist pandemic, providing the platform for users to alter and to show themselves off to the world [with perhaps grandiose hopes of fame], be seen by as many as possible, be ‘liked’, and be instantly gratified – so to speak, by this instant process.

Statigram, a third-party tool on Instagram, functions as a web viewer for statistics. At 11 p.m. PST, December 28, 2012, Statigram’s tallied stats for number of photos tagged ‘selfie’ was 5,509,922. Photos tagged ‘me’ beat ‘selfie’ out of the ballpark, coming in at 72, 657,637. An hour later ‘selfie’ jumped to 5,512,860. A day later, ‘me’ jumps to 73,085,204.

It’s a busy site.

We are drowning in a digital, social-media sea of computer generated, retro-filtered ‘me’ portraits, and Instagram users are posting proof of the takeover of narcissistic traits: displays of pure egocentrism, inordinate self-fascination, exaggerated and excessive preoccupation with vanity. By all appearances, this is an era of ‘it’s all about me’.

I nstagram’s FAQ page states: “We imagine a world more connected through photos.” Lack of empathy, a trait at the heart of narcissism, is the antithesis to connection.

Dr. Jean M. Twenge, Ph.D. Professor of Psychology and author of Generation Meand co-author of The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlementexplains that at the core of narcissism is the fantasy that you are better than you really are (and better than those around you). Any process that allows that fantasy to exist despite the less glamorous reality is an opportunity for narcissism to thrive.

She adds that narcissists aren’t particularly interested in warmth and caring in their relationships, spending a good deal of their time and energy doing things to make themselves look and feel good, and pumping up their egos.

In a September interview with the Washington Times, Dr. Twenge, in response to a question of whether technology has had a negative impact on the younger generation, says, “Technology has mostly been beneficial. But negative consequences can result if technology means people are not seeing each other in person and not connecting on a deep and personal level.”

Appearances aren’t everything. Most of us have learned this somewhere along the way. And yet, the competitive race for keeping up appearances has users in the digital grip of Apple Inc.’s 2011 App of the Year, Instagram, posting at a frantic pace, the moments-to-moments of their selves.

The perilous cultural value placed on how we look, or how we are seen by others, has become malignant in the digital space, and is adding to our already malfunctioning human-to-human, in-the-present-moment daily interactions. We are separating, not connecting – at least not beyond digital appearances.

A world connected through photography is a world in which individually inspired creative expression is neither a race for number of likes, nor an obsessive pre-occupation with sixteen pre-sets to process and post your shot.

The creation of Instagram was a simple, yet inventive solution to something mundane. There is no disputing the photo-altering playground’s creative edge when it comes to re-imagining iPhone snapshots. But, the app’s lightening-speed rise to stardom has usurped the individual’s creative edge, with users hunkering down, millions of times over, into the square tinted box – begging the question of its ultimate impact. And it doesn’t take a psychology degree to notice its sociological effects.

We need to temper our obsession with ‘selfie’ through meaningful in-person encounters and in exploring other facets, formats and tools of photography. Stepping away from the computer – and the mirror, once in a while, and allowing other perspectives to filter through into each of our naturally unique, innately creative personal spaces can also satiate our curiosity to explore ourselves, as well as gift us with the opportunity of seeing ourselves in those we meet, vis-à-vis.

March, 2013

Adore Noir is the world’s first black & white, fine art photography, PDF based, E-magazine. We publish bi-monthly and feature the works and Q&A interviews of six photographers per issue, along with articles covering a wide range of topics such as: Art vs Science.

We aim to be an inspiration to anyone interested in photography and the arts.

Chris Kovacs, editor/publisher

Read this story and all the best stories on The Luminous Landscape

The author has made this story available to Luminous Landscape members only. Upgrade to get instant access to this story and other benefits available only to members.

Why choose us?

Luminous-Landscape is a membership site. Our website contains over 5300 articles on almost every topic, camera, lens and printer you can imagine. Our membership model is simple, just $2 a month ($24.00 USD a year). This $24 gains you access to a wealth of information including all our past and future video tutorials on such topics as Lightroom, Capture One, Printing, file management and dozens of interviews and travel videos.

- New Articles every few days

- All original content found nowhere else on the web

- No Pop Up Google Sense ads – Our advertisers are photo related

- Download/stream video to any device

- NEW videos monthly

- Top well-known photographer contributors

- Posts from industry leaders

- Speciality Photography Workshops

- Mobile device scalable

- Exclusive video interviews

- Special vendor offers for members

- Hands On Product reviews

- FREE – User Forum. One of the most read user forums on the internet

- Access to our community Buy and Sell pages; for members only.