Review By: Sean Reid

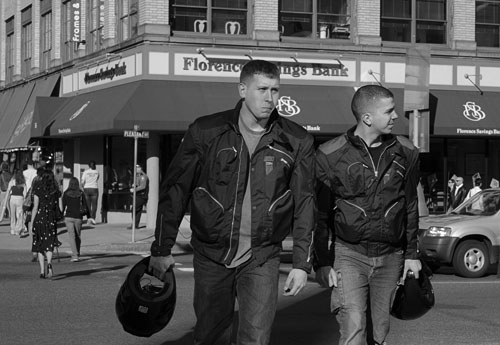

Northampton, Mass., Epson R-D1, Nokton 50/1.5, F/11 @ 1/500 ISO 400

I best beginby describing what this article is and what it isn’t. It is not a definitive lab test of rangefinder lenses; in fact, it isn’t a definitive test at all. Readers seeking rigorous and thorough technical tests of lenses such as the ones I’ve evaluated here should by all means look at the work of lens expert Erwin Puts, whose web site can be foundhere. If you’re primarily looking for that kind of lens information, I recommend ending your read of this article right now and going straight to that site. My approach to testing these lenses is both subjective and pragmatic. There are growing numbers of photographers, professional and amateur, using the Epson R-D1 as their primary camera. Many of them, myself included, are doing photographic work in situations where existing light is sometimes limited and “fast” lenses, lenses that are able to gather large amounts of light, are very desirable. I’m a documentary photographer and the majority of my handheld work is done only by existing light. I am currently faced with choosing which lenses I want to use on the R-D1 in low light situations and this article grew from my own exploration of the options. In the current world of DSLRs and zoom lenses, an F/2.8 lens is often considered “fast”, but for the purposes of this article, I’m defining a fast lens as one that has an F/2.0 or greater maximum aperture. In a strict sense, one cannot fairly compare lenses with very different maximum apertures. An F/1.2 lens, for example, cannot fairly be compared with an F/2.0 lens because the two lenses require very different designs and compromises. Please keep this in mind as you read my comments. That said, however, a photographer choosing, say, a 35mm lens may well be debating between lenses of different maximum apertures. He or she may ask, “What will I give up in performance by going to a faster lens?” “Am I willing to make whatever trade-offs are required for gaining that stop or two?” What I found interesting in the course of doing this test is that one can sometimes gain that extra stop with very little trade-off in picture quality. One cannot necessarily generalize about lens performance based strictly on maximum aperture and some lenses seem to defy conventional wisdom in this respect.

I’m going to take a slightly different approach to this lens review than I did in the previous one. For a long time now, there’s been a great deal of attention paid to numerical measurements of lenses: MTF charts, resolution charts, etc. so much so, in fact, that one might be tempted to think that these numbers can accurately sum up such an individual thing as a lens. It’s important, of course, to be able to quantify a lens’ performance but all too often photographers give attention to those measurements at the expense of the broader picture. To discuss this, it’s probably important that I start by asking the reader to consider that photography is, in many respects, a branch of drawing. This idea is certainly not my own, it was first argued to me by my friend, the photography writer and critic, Ben Lifson*, and the relationship between the lens, photography and drawing has been discussed by many authors since the birth of photography.

Henry Fox Talbot, one of the pioneers of early photography, called his first book of photographs ‘The Pencil of Nature‘. The title’s claim is partly true, I think, although u ltimately, however, the cameras is the pencil of the photographer who has command of the lens, of the shutter, etc.. Cameras, of course, were first created as machines to aid drawing. The lens cast an image on a ground glass and the artist would trace that image onto paper. In some large cameras obscura, an entire room would serve as the camera and one large wall would become a screen of sorts, taking the place of the ground glass. In the digital age, the words ‘image’ and ‘picture’ have come be used synonymously but there is traditionally a distinction between the two. An image is not fixed in permanent or even semi-permanent form; a picture is. Within the system of components we now call a camera, the job of the lens (it’s only job really) is to cast an image on some medium that can record that image, be that a photosensitive glass plate (still used but very rare), a piece of film or an electronic sensor. The image itself is dynamic, the lens does not fix it in time  that is the job of the shutter. The properties of either a chemical process (film, development, printing) or an electronic one (sensor, RAW conversion/camera processing, possible work in Photoshop, sometimes printing) make that image into a picture. The view one sees on the ground glass of an SLR or a view camera is an image, the file or print made from that image is a picture.

Erwin Puts talked about the notion of lens drawing in general when reviewing the Leica 50/1.4 Asph. He wrote:

‘The Noctilux-M is more difficult to profile. If you look at the objectified performance criteria, the Noctilux at the wider apertures is no match for the new Summilux-M. But then we have the more subjective considerations. Here the Summilux offers the real life dimension, where the Noctilux is more dreamlike and painterly in its reproduction of the scenes. The Nokton colour rendition is leaning to the pastel colours where the Summilux is more saturated. The drawing of the Noctilux is with a thick pencil where the Summilux uses a very thin tipped point.’

I discuss this aspect to introduce one way that I will be approaching the various lenses in this test; looking at the ways in which they draw their images on the sensor of the Epson R-D1. There are many kinds of drawing that lenses do but they all fall into two broad categories: 1) The drawing of the parts of a picture that are in focus and 2) The drawing of the parts of a picture that are out of focus (which for the rest of this article, we’ll call ‘OOF’). That latter category is particularly important because this is a test of fast lenses; lenses that allow a photographer more depth of field flexibility when working in various kinds of light and more shutter speed flexibility when working in low light. Of course, any aperture setting can work in low light if the camera’s shutter is left open long enough. Fast lenses, like high ISO films and sensors, allow the photographer to use faster shutter speeds than would otherwise be available to him or her. Naturally of course, the faster a lens is, the less depth of field it has at its maximum aperture. When working at F/2, F/1.4 or especially F/1 there is often far more of a picture that is out of focus than is in focus. So when a fast lens is used at or near it’s maximum aperture, it’s drawing of OOF areas plays a very large role in the look of the final picture. In fact, I think that the particular rendering of OOF areas in a picture, in particular, tends to emphasize the drawing characteristics of a given lens. Pictures from different lenses tend to look a lot more alike at F/8 than they do at F/1.4. I’ll come back to this topic in much more detail further below.

In the last test I did of wide lenses for the R-D1, there was a particular emphasis on vignetting performance and perceived “sharpness” both on center and in the outer zones. The vignetting issue was important to address in those wide lenses but it is far less of an issue for the lenses in this group, which range from 35mm – 75mm. In this review, I’ll present the results of some simple flat field tests, which provide one way of looking at how lenses draw areas that are expected to be in focus, but I’m also going to discuss how the various lenses draw. In some respects, the focus of the latter section is perhaps even more important than the focus of the former. Generally speaking, lenses tend to be graded on their resolution and their contrast. The technical ideals most often discussed refer to a lens being both very sharp and very contrasty. That may not be your ideal, however, and it may not match the way you want your pictures to look.

The great Hungarian photographer André Kertész described his process of making pictures in very simple terms; “I see the thing; I feel the thing; I make the thing.” His statement is true and clear and I’ve let it guide the sequence of this article. I won’t be talking about subject, “I see the thing“, because that’s a matter between the photographer and the world. But I will begin by discussing the lenses as physical objects in the hands (“I feel the thing“) and then talk about the kinds of pictures they draw (“I make the thing“). A photographer generally experiences a lens as a tool in his or her hands long before he or she ever sees what kinds of pictures one can make with it. So I’ll deal with the lenses as tools first and then come back to a discussion of the kinds of pictures these lenses make.

*An aside: Most of Lifson’s writing has been published in print but he also writes a very interestingmonthly column for rawworkflow.com which I highly recommend. In fact, the January, February and April columns are all specifically addressed to various aspects of photography as drawing. I consider the columns to be essential reading for serious photographers.

The Tested Lenses with the Nokton 50/1.5 Mounted on the R-D1

__________________________________________________________________________

As I mentioned above, in this test a fast lens is defined as one that has a maximum aperture of F/2.0 or greater. To my knowledge, the widest rangefinder lenses currently made that have an F/2.0 or faster maximum aperture are the Leica 28/2.0 Summicron Aspherical and the Voigtlander 28/1.9 Ultron Aspherical. Both are excellent lenses and both have already been tested in myprevious reviewof wide lenses for the R-D1. As such, I did not re-test them for this article. Instead, this test concentrated primarily on fast lenses of 35mm and 50mm focal lengths, including current production lenses from Cosina Voigtlander, Leica A.G. and Zeiss. Leica USA was once again kind enough to provide test examples of their lenses and Stephen Gandy ofCameraQuestwas once again kind enough to provide test examples of the Voigtlander lenses. To expand the types of lenses reviewed here I also tested various older fast lenses made by Canon (thanks to the generosity of Canon RF lens owners Jim Williams, Ed Schwartzreic and David Kieltyka). A list of the lenses tested can be found below. I had planned to also test the new Zeiss Planar 50/2.0 but was unable to get a test sample in time for this review. I expect to add a new section to this review after I’ve had the opportunity to test that lens.

The optical performance of a lens (the way it draws an image) is perhaps it’s most important quality to most photographers. The majority of this review concentrates on that aspect specifically. But there are other factors that can have a large influence on how well a lens works as a tool when one is photographing. Rangefinder cameras tend to be lighter and more compact than SLRs and many prefer their RF lenses to be the same. All other qualities being equal (though they usually are not) I think there’s much to be said for a light and compact lens. Longer, thicker lenses can also intrude into the viewing area defined by the viewfinder frame lines. Obviously, since the R-D1 frame lines are parallax-corrected, the degree to which a lens might block the finder framing area will depend on the focus distance set. I like to be able to see what I’m photographing and would prefer not to shoot with a lens that obscures any of the frame from my view. My own approach to photography considers all elements within the frame as subject, be they in focus or out of focus. I can’t make decisions about areas of the frame I can’t see. As such, I always prefer to work with RF lenses that let me see the entire framing area unobstructed. When Kertesz said “I see the thing” he was talking, of course, about the subject of the picture. In my mind, it is indeed very important that one be able to see this subject (in its entirety) in the camera viewfinder. In order to fully see “the thing” in the finder, one’s view must be unobstructed.

The feel of the aperture ring can be important as well when one is working quickly and does not take his or her eye away from the finder. If the aperture stops are precise and distinct, it’s much easier to manually make aperture changes strictly by feel without having to look at the lens barrel.

The performance of the focus ring is important as well. If it’s smooth and well weighted, I find that I can bring the lens into focus more quickly and easily. It’s also a pleasure for the hands to work with a lens whose controls feel solid and precise. The feel of certain lenses inspires confidence in the work they’re going to do. The ratio of the focus ring is important as well and different photographers will have different preferences in this respect. A high ratio focus ring will quickly move the lens through its focus range, perhaps aiding focus in fast work but potentially making adjustments less precise because it is so easy to ‘overshoot’ the ideal focus setting (in either direction). On the other hand, a lens with a low ratio focus ring will be very precise in its adjustments but very slow to focus. There’s an ideal balance between the two extremes that will differ from photographer to photographer. My small-format subject matter is often fast changing and I tend to prefer a slightly higher focus ring ratio.

Current Lenses as Working Tools

Voigtlander 35/1.2 Nokton Aspherical Overall build quality seemed exceptional; very sturdy feeling. The aperture ring, beyond F/1.4 has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct and precise. The focus ring moved smoothly and was well weighted. The focus ring ratio was slower than some others but this seems appropriate given the lens’ very fast F/1.2 maximum aperture and the need that creates for ultra precise focusing. Even without a hood, the 35/1.2 blocked part of the 35mm viewfinder framing area when focused at infinity. Using the Voigtlander LH-3 vented hood, more of the frame area is blocked and about 12% (estimated) of the frame line area is blocked at a focus distance of 2.5 feet. The standard, non-vented, hood of course blocks even more of the frame. The Voigtlander 35/1.2 has an FOV which is not quite as wide as the Canon, Leica and Zeiss lenses, even though all four are nominally 35mm lenses. This does mean that the two 35mm Voigtlander lenses in this test have an FOV that more closely matches the frame lines of the R-D1 than the other lenses. The minimum focus distance is 2.3 feet.

Dimensions: 3′ long by 2.5′ diameter

Weight: 1.1 lb.

$869.00

Leica 35/1.4 Summilux Aspherical Overall build quality seemed exceptional. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct although not quite as precise as the Voigtlander and Zeiss lenses. The focus ring moved smoothly and both the ring weighting and ratio felt perfect to me. Without a lens hood, the lens did not block any of the 35mm frame lines. With the included vented hood mounted, none of the frame area was blocked at infinity focus. Some of the frame area began to be blocked at 6 feet and about 6% (estimated) of the frame line area was blocked at a focus distance of 2.5 feet. The minimum focus distance is 2.3 feet.

Dimensions: 1.8′ long by 2.1′ diameter

Weight: .55 lb.

$2795.00

Voigtlander 35/1.7UltronAspherical Overall build quality seemed excellent. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments (beyond F/2) and each stop felt distinct and precise. The focus action was smooth (although not quite as well damped as some of the more expensive lenses) and the ratio felt spot on. Without a lens hood, the Ultron did not block any of the 35mm frame lines. When the included non-vented hood was mounted it blocked just a little bit of the framing view at a focus distance of about 4 feet. About 2% (estimated) of the frame line area was blocked at a focus distance of 2.5 feet. The Voigtlander 35/1.7 has an FOV which is not quite as wide as the Canon, Leica and Zeiss lenses, even though all four are nominally 35mm lenses. This does mean that the two 35mm Voigtlander lenses in this test have an FOV that more closely matches the frame lines of the R-D1 than the other lenses. The minimum focus distance is 3 feet.

Dimensions: 1.8′ long by 2.2′ diameter

Weight: .44 lb.

$379.00

Zeiss 35/2.0Biogon Overall build quality seemed excellent. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/3 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct and precise. The focus action was smooth and the ratio was perfect. Without a lens hood, the Zeiss did not block any of the 35mm frame lines. I found that the Voigtlander LH-5 vented hood fit this lens perfectly and it began to block just a little bit of the framing view at a focus distance of about 4 feet. About 3% (estimated) of the frame line area was blocked at a focus distance of 2.5 feet. The minimum focus distance is 2.3 feet.

Dimensions: “1.7” long by 2.1′ diameter (est.)

Weight: 8.5 oz.

$1042.00

Voigtlander 40/1.4Nokton Overall build quality seemed very good. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments. Each stop felt distinct but the detents were not as firm as some of the other lenses in the test. The aperture ring has two flared tabs that make it quick and easy to locate the ring by feel (nice design). The focus action was just a little stiff and jerky but the ratio was very good. Without a lens hood, the 40/1.4 did not block any of the 35mm frame lines. With the Voigtlander LH-5 vented hood mounted there was still no significant blocking of the framing area at any focus distance. The minimum focus distance is 2.3 feet.

Dimensions: 1.2′ long by 2.2′ diameter

Weight: 6.2 oz..

$349.00

Leica Noctilux 50/1.0 ÂOverall build quality seemed exceptional. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct and precise. The focus action is well weighted and also very precise. The lens uses a very slow focus ratio for very exact focusing (understandable given its F/1.0 maximum aperture) and I found this made it very difficult for me to keep a fast changing subject in focus. The amount of travel the focus ring requires in order to change focus distance does not, in my experience, make it well-suited to fast changing subjects where one is constantly adjusting focus. The lens includes a built-in hood that telescopes from the lens body. It’s a very simple and useful design. Without the hood extended, the lens blocks about 5% of the 50mm frame lines at infinity focus and about 10% at about 3 feet. With the hood extended, the lens blocks about 10% of the 50mm frame lines at infinity focus and about 15% at about 3 feet. The minimum focus distance is 3.3 feet.

Dimensions: 2.4′ long by 2.7′ diameter

Weight: 1.39 lbs.

$3295.00

Leica 50/1.4 Summilux Aspherical –Overall build quality seemed exceptional. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct although not quite as precise as the Voigtlander and Zeiss lenses. The focus ring moved smoothly and both the ring weighting and ratio were excellent. The lens includes a built-in hood that telescopes from the lens body and then locks in place with a quick twist. It’s a different design than the one used on the Leica 50/2.0 but it’s is equally ingenious and useful. When the hood is extended, it just starts to enter the 50mm framing area at 3.5 feet focus distance and intrudes into about 2% of the frame at 2.5 feet. The minimum focus distance is 2.3 feet.Dimensions: 2.1′ long by 2.1′ diameter

Weight: 11.8 oz.

$2495.00

Epson R-D1, Nokton 50/1.5 Asph., 1/60 sec. at ISO 1600

Voigtlander Nokton 50/1.5 Aspherical– Overall build quality seemed exceptional; very sturdy feeling. The aperture ring, beyond F/2 has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct and precise. The focus ring moved smoothly and was well weighted. The focus ratio seemed spot on for an F/1.5 lens. With or without the included non-vented lens hood mounted there was no noticeable blocking of the 50mm frame lines at any focus distance. The minimum focus distance is 3 feet.

Dimensions: 2.2′ long by 2.3′ diameter

Weight: .53 lbs.

$329.00

Leica 50/2.0 Summicron– Overall build quality seemed exceptional. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct although not quite as precise as the Voigtlander and Zeiss lenses. The focus ring was beautifully damped and weighted, giving superb focus feel. This was one of the fastest lens to focus in the test and the focus ratio felt perfect for an F/2 lens. The lens has a slide-out hood built into its body which is a great and very useful design. The lens is compact when stored then the hood slides out quickly and easily for use and one never has to worry about losing it. Brilliant. With or without the hood extended, the lens did not block any of the 50mm frame area at any focus distance. The minimum focus distance is 2.3 feet.

Dimensions: 1.7′ long by 2.1′ diameter

Weight: .53 lb.

$1295.00

Leica 75/1.4 Summilux –Overall build quality seemed exceptional. The aperture ring has click stops in 1/2 f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct and precise. The focus ring moved smoothly and both the ring weighting and ratio were excellent. The lens includes a built-in hood that telescopes from the lens body. It’s a different design than the one used on the Leica 50/2.0 but it’s is equally ingenious and useful. Using this lens on the R-D1 would require a 115mm FOV-equiv. finder which I did not have available for this test. In fact, I don’t know if anyone yet makes a correct finder for this combination. The minimum focus distance is 2.4 feet.

Dimensions: 3.1′ long by 2.7′ diameter

Weight: 1.3lbs.

$2995.00

Older Lenses as Working Tools

Canon 35/1.5Â Overall build quality seemed excellent. The example I borrowed of this old lens was in need of some lubrication so it would not be fair to assess its focus feel or weighting. The aperture ring has click stops in whole f/stop increments and each stop felt distinct although not as precise as the modern lenses in the test. The lens’ design provides a certain amount of shading even without a hood and the lens did not block any of the frame area at any focus distance.

Canon 35/2.0Â Overall build quality seemed excellent. The example I borrowed of this lens was in superb condition and the focus action was buttery smooth and nicely weighted. The focus ratio seemed spot-on for an F/2 lens. The aperture ring has click stops in whole f/stop increments but the detents for each stop are not as pronounced or precise as those on the modern lenses. The lens’ design provides a certain amount of shading even without a hood and the lens did not block any of the frame area at any focus distance.

Canon 50/1.2 ÂOverall build quality seemed excellent. The example I borrowed of this lens was in very good condition but needed a little lubrication so the focus and aperture rings were both a little stiff. The focus ratio seemed about right for an F/1.2 lens. The aperture ring has click stops in whole f/stop increments and the detents are fairly pronounced. I did not have a lens hood to test this lens with but the lens body itself did not block the 50mm framing area at any focus distance.

Canon 50/1.4 ÂOverall build quality seemed excellent. The example I borrowed of this lens was in excellent condition and the focus action was fairly smooth. The focus ratio seemed right for an F/1.4 lens. The aperture ring has click stops in whole f/stop increments and the detents are fairly pronounced. This particular example of the lens had a slightly stiff aperture ring but it was likely just in need of lubrication. Using an M48 to M52 adapter, I was able to fit the non-vented hood from the CV 50/1.5 on this lens and with or without that mounted there was no noticeable blocking of the 50mm frame lines at any focus distance.

Canon 50/1.8– Overall build quality seemed excellent. The example I borrowed of this lens was in good condition and the focus action was fairly smooth. The focus ratio seemed right for an F/1.8 lens. The aperture ring has click stops in whole f/stop increments and the detents are fairly pronounced. This particular example of the lens had a slightly stiff aperture ring but it was likely just in need of lubrication. I did not have a lens hood to test this lens with but the lens body itself did not block the 50mm framing area at any focus distance.

__________________________________________________________________________

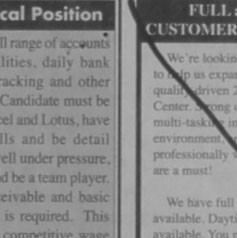

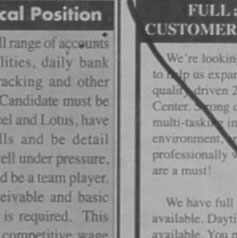

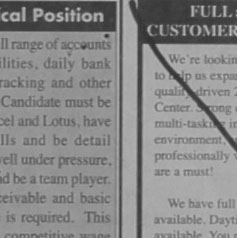

Flat Field Sample Pictures: Newsprint

The samples below were made by photographing sheets of newspaper fastened to a flat board with the camera carefully aligned so as to be parallel with the board on it’s vertical and horizontal axis. The focus distance was approximately 42″ and the newspapers were lit by consistent artificial lighting (professional quartz lighting bounced into an umbrella). Each lens was focused at three distances in order to minimize potential focusing error: 1) At the distance indicated by the rangefinder, 2) just slightly ahead of the indicated distance, 3) just slightly behind the indicated distance. In each case, I kept the sharpest result for each lens at each tested aperture and discarded the others. Some of the lens samples seem blurry enough that one might wonder if the lens was not focused correctly. I don’t believe that to be the case, however, as I did multiple tests of any lens that did not appear to be sharp wide open. In any case, the examples below represent the best focus I could achieve using my R-D1 body.

Some lens experts may argue for the limitations of a flat field test but I have generally found that the lenses that seem sharpest in my simple newspaper tests retain that quality in normal picture making when I test them in the field. In the interests of consistency, all files for this test were captured in RAW mode at ISO 200 and processed to B&W in Epson PhotoRAW at default settings. Needless to say, words like “sharp” and “soft” are not quite exact terms they’re when used to describe a lens. So, rather than get into verbal descriptions of these results I will simply present the picture crops in the tables below and let the reader draw his or her own conclusions from them. Once again, of course, “fair” comparisons among these samples can only be made between lenses of similar focal lengths and similar maximum apertures. That said, I invite the reader to make all the unfair comparisons he or she would like to, inasmuch as the “unfair” comparisons may be useful in weighing the pros and cons of the various lenses..

It’s also worth keeping in mind that all rangefinder cameras have a certain small amount of imprecision inherent in their focusing; see Irwin Put’s discussion on this topichere. There is also often bound to be a little human error involved, from time to time, when one uses a rangefinder system, no matter how experienced the user may be. (In fact, it’s a losing battle in a sense, the older we get, the more experience we have with rangefinders but the more our eye sight deteriorates. <G>) This being the case, I think that small differences in perceived sharpness among these lenses may not amount to much in real world use. This is especially true for fast lenses like these when they’re used in low light, hand-held at slower shutter speeds.

Center Section Crops from 100% Size Files

F/1.4 ~ F/1.5

F/2.0

F/2.8

Aspherical

N/A

N/A

N/A

Aspherical

N/A

N/A

Upper Left Corner Crops from 100% Size Files

F/1.4 ~ F/1.5

F/2.0

F/2.8

Aspherical

N/A

N/A

N/A

Aspherical

N/A

N/A

Leica 75/1.4 Summilux

The Leica 75/1.4 Summilux could not be focused reliably by my example of the Epson R-D1. All of the other lenses in this test could be focused reliably (although the Noctilux was sometimes a challenge). On the R-D1, the 75 shows about a 115mm FOV. At F/1.4, with the R-D1’s fairly short rangefinder base length, the lens often ended up being focused ahead of or behind it’s target distance when the rangefinder mechanism indicated correct focus. So while some people have reported this lens being useable on the R-D1, wide open, I cannot recommend that combination. Professional assignments, in particular, normally demand that focus be spot-on and I would not want to take that risk with this lens on the Epson. That said, when the 75/1.4 was correctly focused, it was fairly sharp on center and in the outer zones, even at F/1.4. By F/2.8, it was extremely sharp all the way across the frame and it, as we might expect, was still sharp at F/8.

__________________________________________________________________________

And Now to Look More Closely at the Drawing

There are many distinct differences in the ways various parts of the frame are drawn in the sample pictures made by these various lenses. There’s also no hard and fast rule about what kind of drawing (of areas in-focus or out-of-focus) is ‘best’. Conventionally, we look at lenses to provide high resolution, high contrast, etc. But for a serious photographer (professional or amateur), setting criteria like that is, to some extent, putting the cart before the horse. Deciding on what kind of drawing one wants a lens to do should be the first task. Then one can look at which lenses best accomplish that. Some lenses tend to be soft on center and even softer in the outer zones (such as the Canon 35/1.5). Some, like the Summilux 50/1.4 ASPH are bitingly sharp on center but not quite as sharp in the outer zones. Some, like the new Zeiss Biogon 35/2.0, are nearly as sharp in the outer zones as they are in the center  the sharpness is fairly evenly distributed across the frame. There’s no one way of lens drawing that works best for all kinds of photography. Choosing a particular lens is, in part, one of the first things a photographer does to determine how he or she is going to make the camera draw.

It’s rare that the various elements within a picture are all at the same distance from the lens. Working at wide apertures such as F/1.0 to F/2.0, depth of field is of course very narrow so only a very small range of distances from the lens are perceived as sharp in the final print. Very often that focus distance is set for people or objects at or near the central area of the frame. As such, one might think that the edge/corner performance of a lens set to a wide aperture is not so important because picture elements towards the outer edges of the frame are likely to be at a different distance from the lens than the distance its focus is set to. As such, DOF limitations will often take those other distances out of focus. But, as became clear to me while I was doing these tests, the degree to which a lens is sharp across it’s field at wide apertures still influences the look of subjects seen across that field even as they go out of focus due to depth of field. A lens that is sharp from center to outer zones at F/1.4 gives a different look to OOF areas than one that is sharp on center but soft in the outer zones. I found that the lenses I liked most for their OOF drawing in the outer zones (at large apertures) were often the same lenses that held fairly sharp focus from corner to corner wide open. This is not an objective advantage necessarily but, rather, a quality that may or may not appeal to individual taste. The degree to which a lens holds micro-contrast at the edges and outer zones of a frame also influences the look of OOF areas. A lens like the Noctilux, for example, is soft in the outer zones wide open but it still holds a good amount of micro-contrast across the frame even at F/1. This of course changes the way it draws.

Color is such a powerful visual force that it can sometimes tend to distract the eye from subtler aspects of a picture. As such, I found it useful to look at these samples in B&W (conversions from RAW in Epson PhotoRAW) so as to concentrate my attention on the way each lens drew it’s image with the aperture wide open. I’ll concentrate below on some comparison sets of lenses that have distinctly different ways of drawing. Later on, I’ll also provide color samples from each lens as well so that the reader can see how each one renders color.

One would want to have a well-calibrated monitor to fully appreciate the differences among these samples presented in the sections below. Even then, the differences are not as pronounced on a computer monitor as they are in quadtone prints. My comments come from looking closely at prints and at 100% files but I’ve reproduced croppings here to provide some approximate examples of the differences I see among these lenses. These samples were made with my oldest daughter as model sitting at a table in the beautiful restaurant of theFullerton Innin Chester, Vermont. The camera was set to ISO 400.

Canon 50/1.4, Nokton 50/1.5 and Summilux 50/1.4

Voigtlander 50/1.5 Nokton Aspherical at F/1.5

Let’s start with three lenses that draw a bit differently even at F/8. Consider the look of the little pewter cream container in the lower left corner of the sample pictures from theSummilux 50/1.4at F/8, theNokton 50/1.5at F/8 and theCanon 50/1.4at F/8. All three lenses are fairly sharp in the corners at this aperture yet each lens draws this part of the scene a little bit differently. The Summilux lens shows the greatest amount of micro-contrast in the outer zones so that the various planes that make up the two visible sides of that container are more distinct in tone. With the Summilux lens, the seam that joins these planes is distinctly brighter than either of the sides themselves. The result is that the object itself seems more distinct, more three dimensional, more solidly itself. To my eye, and this is highly subjective, this kind of drawing of OOF areas is particularly beautiful. The Summilux 50/1.4 (much like the Summilux 35/1.4) also tends to lift the midtone values so that all tones above, say, 50% K or so, are lighter than they are with Nokton 50 or with the Canon 50/1.4. This tends to give pictures made with the Summilux a kind of airiness but it also means that higher values can more easily push off the histogram into pure white with no detail. Using the combination of the Summilux and the R-D1, one would want to be very careful not to unintentionally lose the detail in, for example, a bride’s white dress in sunlight. The Nokton 50/1.5 shows just a little bit less micro-contrast and this changes the way it draws. The Canon 50/1.4 has a somewhat lower level of micro-contrast and this is particularly evident in the way the very upper tones are held in. With the Canon, the tonal transitions are very gentle and very subtle. The Leica lens tends to open up the space, the Canon tends to compress it and the Nokton splits the difference. Neither effect is inherently better, per se, it’s all question of what kind of picture a photographer wants to make. (I must apologize that the Leica sample for this set is focused slightly ahead of the other two but fortunately that has little effect on micro-contrast.)

Voigtlander 50/1.5Aspherical@F/8

Canon 50/1.4@F/8

It’s not evident in the samples directly above but looking at other example pictures (made in bright sunlight) it became clear to me that theNokton50has a slight tendency to push the lower tones towards black and I could readily see this in the histograms of the Nokton 50 files (after they had been converted from RAW using default settings in PhotoRAW). This tends to block shadow detail and may be part of the reason that some describe the Nokton’s OOF rendering as being slightly harsh. Of course, a harsh rendering of OOF shadows could be a good or bad thing depending on what kind of picture one is trying to make. A given rendering of an OOF area might be either too harsh or not nearly harsh enough. Some of thatNoktonshadow detail (down near Zone II and III for those of you who use the Zone System) can be recovered during RAW conversion and of course, as with nearly all digital files, it’s a bit easier to recover shadow detail than highlight detail. The downside of that shadow recovery (if used with high ISO files) is that it can bring up any noise levels in those shadows while it’s bringing up their tone. That said, the Nokton files respond very well to less aggressive black point settings during conversion in Epson PhotoRAW. I find that using a moderate black point for conversions in that program can very effectively open up the lower shadows and greatly lessen any sense of harshness in the OOF areas. The default Epson PhotoRAW black point is (in my view) too aggressive for the Nokton just as the default PhotoRAW white point is too aggressive for the Leica asphericals. In a sense, one can dial in the amount of “harshness” (at least one type of it) by varying the black point setting in RAW conversion. I used the Nokton 50 extensively on a recent wedding assignment and the final files (converted with a less aggressive black point setting) don’t seem harsh at all. And, again, sometimes harshness is just what a picture needs.

I certainly do recommend shooting in RAW mode when working with very contrasty lenses such as theNoktonand theSummiluxbecause RAW does give one a bit more dynamic range to work with while allowing one to reset those black and white points in PhotoRAW. This can make a significant difference in how these lenses render shadows and midtones. If one is converting in Epson’s PhotoRAW, sometimes just backing off the default contrast setting a couple clicks will be be enough to hold detail across the scale from shadows to highlights but I prefer to use that contrast setting to specify the initial midtone separation and then to dial in the shadows and highlights via the white point and black point settings. Certainly, with lenses like these two and contrasty subject lighting, variations in RAW processing settings can make particularly noticeable differences in the look of the final files. One request I made of Epson in a recent phone conference is that PhotoRAW be modified so that one can specify the settings used for batch conversions so that one can modify these kinds of settings and then apply to them to a specific batch.

Noctilux 50/1.0 and Canon 50/1.2

Canon 50/1.2 @F/1.2

Now let’s look at two of the fastest lenses in the test, theLeicaNoctiluxand theCanon 50/1.2. The Noctilux, which is soft in the outer zones wide open, combines that softness with a fairly high level of micro-contrast. The Canon is softer still but combines that with a very low level of micro-contrast. Looking again at that same cream container, one can see that the way each lens draws it is very distinctly different. With Noctilux, the container has the strange combined quality of being both soft and sketched while at the same time still being quite distinct in its form and in its shape (largely because of the micro-contrast). It tends towards being ethereal but it doesn’t quite get there (an interesting tension). With the Canon, the container becomes so soft and has so little contrast that it almost seems to be seen through a kind of Vaseline haze; it glows a little bit, like some scenes do in early Hollywood movies. By most objective criteria, this Canon lens does quite poorly in the outer zones wide open (little contrast, very soft, etc.). Yet, to some eyes, the look this creates could be very appealing. It’s a different kind of drawing, not necessarily better or worse, in visual terms, but simply different.

Canon 50/1.2@F/1.2

Canon 35/1.5, Leica 35/1.4 ASPH and Nokton 35/1.2

Leica 35/1.4 Summilux Aspherical at F/1.4

We know from the newspaper tests above that the Canon 35/1.5 is softer wide open than the Summilux 35 or Nokton 35 but there’s enough sharpness there to make a good basic drawing of my daughter’s face and hands. It isn’t very detailed but it isn’t quite as approximate as a sketch either. The OOF objects, such as the napkin in the foreground, take on what I think of as the ‘Canon rangefinder lens glow‘; they’re very soft and have very little contrast. There’s hardly a recognizable solid line, to speak of, to be found anywhere in the OOF sections of the picture. What we mostly see are very gradual and subtle changes in tone and these are mostly what distinguish one object or surface from another. There’s a little bit of the feeling we get when looking at a watercolor or a drawing done with a wash.

Withthe Leica 35/1.4 we see a truly different kind of drawing at the same focal length and about the same aperture as the Canon 35/1.5. Here we see every freckle on my daughter’s face, every strand of hair, the dryness of her lower lip (from a long Vermont winter), the texture of the skin on her hands  everything is drawn with a very fine-tipped pencil. As our eye moves to the OOF areas (such as the napkin), they’re clearly OOF but they still retain a kind of precision where individual lines and edges, while not sharp, are quite distinct and defined. The lens’ contrast and its tendency to push highlights towards pure white makes for fairly pronounced transitions from one surface to another and from one object to another. The drawing, not surprisingly, is similar to what we see from the Leica 50/1.4 Summilux. Even at F/1.2, the Nokton 35 is slightly sharper than the Canon 35/1.5 at F/1.5 and shows more micro-contrast. Much like it’s 50mm brother, this Voigtlander lens makes a drawing that’s somewhere in between that of the Leica and the Canon. In the corners, it has neither the Canon’s hazy glow not the Leica’s precise edges. On center it’s sharper than the Canon 35/1.5 (this is more evident in prints than it is on screen) but not nearly as sharp as the Leica.

Leica 35/1.4Aspherical@F/1.4

Voigtlander 35/1.2@F/1.2

Canon 35/2.0 and Biogon 35/2.0

Zeiss 35/2 Biogon at F/2

On center wide open, the Canon 35/2.0 and Zeiss Biogon 35/2.0 both draw quite similarly. The distinctive difference between the two is in the outer zones where the Zeiss is very sharp and thus draws with great precision, even when the objects it draws are not located at the set focus distance. While the two lenses convey essentially the same depth of field at F/2.0 (in a technical and exact sense) the actual drawings they make of OOF areas are quite different. Looking again at that napkin, the Canon rendering gives the typical “Canon lens glow”, the glass and napkin arejust barely there; they have kind of the haziness we might imagine seeing in a mirage. To some eyes, they may seem to be less a representation of something real and more a picture of something imagined. The glass and napkin drawn by the Zeiss lens, on the other hand, seem more solid, more physical, more present and more real. While no photograph can truly be realistic, the Zeiss lens tends to make it that way in the outer zones. I can envision myself picking up the glass presented to us by the Zeiss and filling it with water. With the glass presented to me by the Canon, I have the sense that my hand might pass right through it when I tried to pick it up. Which lens is better? Again – what kind of picture are you making?

Note: The Voigtlander 35/1.7 was not yet available for testing at the time these Fullerton Inn samples were made.

Zeiss 35/2.0Biogon@F/2.0

__________________________________________________________________________

Sunny Day Lenses

Having worked with the R-D1 for several months now, I’m beginning to think that an ideal kit for the camera, for me, could include both ‘standard’ and ‘sunny day’ lenses. To understand first the technical reasoning behind this suggestion, the reader may want to read my review of wide lenses on the R-D1. These ‘standard’ lenses would be used in any kind of lower to moderate contrast existing light. In those circumstances, lenses that relay high subject contrast will not necessarily present a broader range of contrast to the sensor than it can record. The subject contrast, lens contrast and sensor’s dynamic range all end up being well-matched. Most of the modern lenses in this test could fall into that category.

But there may also be times, or styles of work, in which the somewhat harsher and more contrasty drawing of these very modern lensesin bright sunlightis just right for the kind of pictures the photographer wants to make. Sometimes the highlights in a picture should blow out to pure white and/or the shadows push down to heavy black. A lens like the Leica 50/1.4 Asph used in bright sunlight tend to create pictures where the lines and the tonal transitions are crisp and somewhat abrupt, each tone of the picture tends to announce itself as a distinct entity. Each region of the picture that is defined by tone becomes almost a shape unto itself. The central subject edges defined by a lens like the Leica 50/1.4 aspherical are almost like pieces of broken glass seen in sunlight. Add color to the mixture and the combined effect has tremendous, almost dizzying, intensity. The various surfaces in the picture push and pop towards the viewer almost as if they were coming up off the print or screen. The sense of three-dimensionality that some photographers love so much is present in spades. If this is the way one wants his or her camera to draw in bright sunlight than these very modern, very contrasty lenses may be exactly what he or she ever needs. Sometimes a picture should whisper and sometimes it should shout.

Burlington, VT, Epson R-D1, Summilux 50/1.4 Asph., F/8 @1/631 ISO 400

About that whisperingâ�¦for that one might also choose to keep a set of lower contrast lenses to use on bright sunny days when the desired effect is less intense, gentler, more gradual. This, I believe, is the province of the older RF lenses such as many made in the 1950s and 1960s by Canon and Leica. I first came across this kind of R-D1 drawing when using a borrowed Canon 28/2.8 (at about F/8 or F/11) on the R-D1 when shooting on city streets in bright sunlight. This lens, which is technically flawed in many ways, tends to tame the light somewhat in at least two respects. First, by reducing the macro contrast of the scene, it preserves more detail in both the shadows and the highlights. Second, its lower levels of micro-contrast soften the transitions between midtones, making them more gradual and subtle. The lens tends to whisper. The shapes in the picture tend to merge into each other somewhat rather than announcing themselves as distinct entities. The Canon 28/2.8 has a rather strange handling of color that would not be to everyone’s liking but it’s handling of B&W (the dominant medium during the era in which it was designed) is, to my eye, particularly elegant and beautiful. Within this present test, the lenses that draw most like the Canon 28/2.8 (with respect to contrast) in bright sunlight are the, not surprisingly, the Canon 50/1.8 and to a somewhat lesser extent, the Canon 50/1.4 and 35/2.0.

So one could then also keep a set of older lenses like this (many of them quite compact and inexpensive) to make subtler pictures in high contrast light, such as shooting on the streets of a city on a sunny day. These lower contrast lenses, used at perhaps F/5.6 Â F/16, reduce the subject contrast before it is projected on the sensor, thereby effectively increasing the sensor’s dynamic range. The highlights retain detail without the photographer needing to resort to under-exposing the shadows. Having tested many RF lenses on the R-D1, I find the older Canon lenses to be my favorite choices for B&W work in bright outdoor light, given the way in which I want to have the camera draw. Some of these older lenses aren’t very sharp in the outer zones wide open but by F/5.6 or so they are fairly sharp across the frame while still having lower macro and micro-contrast than more modern lenses. Certain older Leica lenses, with their lower macro contrast, would also potentially work well also as ‘sunny day lenses’ for this kind drawing. Once again, these are old lenses that, by the numbers, are clearly outperformed by more modern lenses in almost all respects. Yet, for certain kinds of pictures and/or certain kinds of photographers, they make a more suitable drawing.

Northampton, Massachusetts, Epson R-D1,

Canon 50/1.8, F/11 @ 1/500 ISO 400

__________________________________________________________________________

Preservation of Detail Across the Dynamic Range of the R-D1

35mm lenses

Within the current group of 35mm lenses tested, it was the two older Canon lenses that provided the most useable dynamic range to the R-D1 according to outdoor tests I did on a bright sunny day (using F/8 at 1/500, converting RAW to 16-bit TIFF in Epson PhotoRAW). Looking at the histograms, the two 35mm Canon lenses were able to present almost the full contrast range of the scene I photographed with very minimal clipping of the highlights or shadows. Of the current 35mm lenses tested the Leica 35 Summilux held slightly better shadow detail than the Voigtlander 35 Nokton which in turn held slightly better shadow detail than the Zeiss 35 Biogon. All three of the modern lenses pushed some of the highlight detail off the right edge of the histogram. The Voigtlander 35 Nokton held the best highlight detail of the modern lenses. The Voigtlander 35/1.7 was next best and the Leica 35 Summilux clipped the most highlight detail. It’s been my experience having tested several of the Leica aspherical lenses that they are just a bit ‘hot’ at the upper edge of the tonal range. They tend to push the very upper highlight tones to pure white in contrasty light.

Preservation of Detail Across the Dynamic Range of the R-D1: 35 – 40mm lenses

1. Canon 35/2.0 2. Canon 35/1.5 3. Voigtlander 35/1.7 Ultron 4. Voigtlander Nokton 35/1.2 5. Voigtlander 40/1.4 6. Zeiss 35/2.0 Biogon 7. Leica 35/1.4 Summilux50mm lenses

Among the group of 50mm lenses tested, it was again two of the older Canon lenses that provided the best dynamic range for the R-D1 according to outdoor tests I did on a bright sunny day (using F/8 at 1/250, converting RAW to 16-bit TIFF in Epson PhotoRAW). Looking at the histograms, the Canon 50/1.4 and Canon 50/1.8 lenses were able to present almost the full contrast range of the scene I photographed with very minimal clipping of the highlights or shadows. Of the modern lenses, the Noctilux did the best job of holding highlight detail without clipping and it also held shadow detail nearly as well as the three older Canon lenses. The other two Leica 50mm lenses both held slightly more shadow detail than the Voigtlander 50/1.5 Nokton. All three of the modern 50mm lenses pushed some of the highlight detail off the right edge of the histogram. Once again, it was the Leica 50/1.4 aspherical that had the strongest tendency to clip upper highlights so that they went to pure white. The other three modern lenses all did somewhat better in that respect.

Preservation of Detail Across the Dynamic Range of the R-D1: 50mm lenses

1.Canon 50/1.4

2. Canon 50/1.8

3. Canon 50/1.2

4. Leica Noctilux

5. Leica 50/2.0 Summicron (non-asph)

6. Voigtlander 50/1.5 Nokton

7. Leica 50/1.4 Summilux

Essentially, some of these modern lenses convey scene contrast so well that they easily exceed the dynamic range limits of the R-D1 (which has a similar dynamic range to many DSLRs) as well as the dynamic range of many films, depending on their type and processing. As I mentioned above, however, setting less aggressive white and black points (than the default settings) during conversion in Epson PhotoRAW can of course expand the range of shadow and highlight detail present in files made with these lenses.

__________________________________________________________________________

Color Samples

These files below were all made in natural light at ISO 200 at F/8, captured in RAW and converted to JPEG in Epson PhotoRAW using default settings except for a white balance correction that was applied in the same way to all files. Please ignore minor differences in focus. These are lower left-hand corner crops from 25% size files.

Leica 35/1.4 Summilux

Aspherical

Canon 35/1.5

Voigtlander 35/1.7 Ultron

Zeiss 35/2.0 Biogon

Canon 50/1.2

Aspherical

Canon 50/1.4

Leica 50/2.0

__________________________________________________________________________

The Sweet SpotIn my mind, F/1.4 is a real sweet spot for fast rangefinder lenses. The DOF wide open at F/1.4 is thin but not razor thin, the lenses are a full stop faster than F/2 yet most are lighter and more compact than the F/1.0 or F/1.2 lenses. The F/1.0 Noctilux is a very special lens, not only for its speed but also for its distinct way of drawing which is both soft (in terms of focus) and contrasty at the same time. For those who love it, there is no substitute. But it’s large, heavy and not easy to focus wide-open with consistent accuracy on the R-D1. I much preferred the Leica 50/1.4 and Voigtlander Nokton 50/1.5 to the Noctilux (when using the Epson rangefinder). The former two give up about a stop to the latter but they are lighter, smaller, block much less of the finder and focus more quickly and reliably on the R-D1. The Voigtlander 35/1.2 is a very good lens but, like the Noctilux, it is large, heavy and blocks a noticeable portion of the finder framing area. I myself would prefer to give up the half-stop advantage the 35 Nokton has over the Leica 35/1.4 in favor of the latter’s more compact and lighter body. The chief advantage the 35 Nokton has over the Leica 35/1.4 is price and that advantage is significant. It would be very interesting to see Voigtlander produce a fairly compact 35/1.4 Nokton that performs as well as their exceptional 50/1.5 Nokton.

__________________________________________________________________________

My Favorites of the Fast Lenses

Favorite Ultra-fast lens for the R-D1:

Voigtlander 35/1.2 Aspherical

If Money Is No Object:Leica 28/2.0 AsphericalorVoigtlander Ultron 28/1.9 Aspherical

Leica 35/1.4 AsphericalorZeiss Biogon 35/2.0

Leica 50/1.4 Aspherical

Cost Considered:

Voigtlander Ultron 28/1.9 Aspherical

Zeiss Biogon 35/2.0 orVoigtlander Ultron 35/1.7 Aspherical

Voigtlander 50/1.5 Aspherical

Favorite Sunny Day Lenses:

Canon 28/2.8 (very compact, low macro-contrast)

Voigtlander Ultron 28/1.9 ASPH (moderate macro-contrast)

Canon 35/2.0orCanon 35/2.8 (very compact, low macro-contrast)

Canon 50/1.8orCanon 50/1.4 (low macro-contrast)

__________________________________________________________________________

Summary Comments

My summary comments below are based on my experiences using these lenses to photograph a wide variety of subjects over a period of about six weeks. The results of the flat field tests and comparative scene tests that I present above factored into my impressions but perhaps more important were the thousands pictures I made with these lenses under a wide range of circumstances. When one uses a lens for a variety of work, he or she starts to get a general feel for how it draws in various kinds of light and those general impressions can be as valuable, I think, as the results of specific tests. I paid the most attention to my gut reactions to the files during those first few seconds that passed immediately after I opened each one in Photoshop – that was the most valuable impression for me, the immediate visual impression one experiences before he or she can begin to think and rationalize about a lens’ performance. My four favorite lenses, listed just below, all struck hard from the first few moments I looked at their drawings. Each one made me draw in my breath a little and whisper “wow” to myself.

Overall, TheLeica 35/1.4 Summilux Aspherical, Leica 50/1.4 Summilux Aspherical, Zeiss 35/2.0 Biogonand theVoigtlander50/1.5 Noktonwere my favorites in the test. All four of those lenses consistently delivered files that impressed me under all kinds of conditions with all kinds of subjects. This was true whether they were used wide open or stopped down. TheVoigtlander 28/1.9 Ultronlens I tested previously is also a great performer on the R-D1. My own ideal lens kit for this camera would complement those five modern lenses with a set of the lower contrast older Canon lenses (28mm, 35mm and 50mm) because of the way the latter draw B&W images when one is photographing in bright sunlight.

Leica 35/1.4 Summilux ASPHÂ The 35/1.4 is very fast, compact, lightweight, sharp and has an absolutely beautiful way of rendering both in-focus and OOF areas. This is a wonderful lens in nearly all respects though it has a tendency to over-expose the highlights in contrasty light.

Zeiss 35/2.0Biogon This is a very impressive little lens. Wide open, it’s not as sharp on center as the Leica 35/1.4 is at F/2 or even at F/1.4 but its performance in the outer zones, even wide open, is truly exceptional, better than any other 35mm lens in the test.. Micro-contrast is a little lower than that of the Leica 35/1.4. This is one of those lenses that made me pause and just stare for a moment when I first opened the files in Photoshop. Like the two Leica F/1.4 lenses, it has a beautiful way of rendering both in and out of focus areas. It is a great lens, although like the Leica 35/1.4 it does have a slight tendency to overexpose the highlights in contrasty light. I’m sure that many are curious as to how the 35 Biogon compares to the Leica 35/2.0 ASPH but unfortunately, I didn’t have one of the latter on hand to compare with. The Zeiss draws differently than the Leica 35/1.4 but is equally worthy of consideration for photographers who don’t need the extra aperture speed of the 35/1.4. The Zeiss is also less than half the price of the Leica.

Voigtlander 35/1.2 Nokton This is the fastest 35mm RF lens ever made and it performs quite well overall. It doesn’t quite have the kind of stunning sharpness wide open that the Leica 35/1.4 has but it is fairly sharp as well as being faster and much less expensive than the Leica. Unfortunately, it’s also much larger and heavier than the Leica 35/1.4. I prefer the Leica’s size, weight, sharpness and OOF rendering. The Voigtlander 35/1.2 is an excellent lens that just happens to be overshadowed, in my view, by a superb lens  the Leica 35/1.4 Asph. Overshadowed, that is, if one does not consider price: the Voigtlander costs only $869.00 vs. the $2795.00 cost of the Leica.

Voigtlander 35/1.7– While ultimately this lens cannot quite match the Summilux or Biogon in terms of its overall performance, it still performs quite well and is much less expensive than the Leica or the Zeiss. Wide open, it’s sharper than the Zeiss or Canon lenses on center. In the outer zones wide open it’s sharper than the Nokton 35/1.2 or the Canon lenses. So overall it’s a very competent performer as well as being the least expensive modern 35mm lens in the test ($379.00). It’s macro contrast is lower than that of most other modern lenses in the test and that could make it a good match for the R-D1 on a sunny day. The first copy of this lens that I received was defective and performed quite poorly (it was the first time I’ve run into a defective lens from CV). The second copy rfor m ed much better and the comments in this test refer to that second copy.

Canon 35/2.0 - This very compact and lightweight lens can’t match the more modern lenses in the outer zones at large apertures but its center sharpness is quite good. If a lower contrast lens with strong center sharpness appeals to you, the Canon 35/2 is worth considering, especially as a ‘sunny day’ lens. By F/8 it’s fairly sharp across the frame. Its size and weight are strong assets and its design provides a certain amount of lens shading even without a hood.

Canon 35/1.5 - This is a great pictorialists’ lens at wide apertures, it’s fairly soft on center and even softer in the outer zones. In terms of absolute sharpness and contrast it isn’t in the same league as the Voigtlander, Leica or Zeiss but it does have a very distinct soft way of drawing that may appeal to some photographers for certain kinds of work.

Voigtlander 40/1.4 Nokton –If one doesn’t mind adapting to the FOV of this lens (relative to the R-D1 frame lines when set to 35mm) it could be an excellent choice. I prefer the near 50mm FOV of the 35mm lenses to the near 60mm FOV of this lens but it certainly performed quite well in this test. Add in the fact that it’s quite fast, compact and reasonably priced at $349.00 and one would be hard-pressed to find a better value for a lens with a 60mm FOV. I prefer the Ultron 35/1.7 to this lens (on the R-D1) purely for its wider FOV but if this Nokton were a 35/1.4 I think I’d buy it in a heartbeat.

Leica 50/1.4 Summilux ASPH – This lens is so sharp on center, even wide open, that the first time I saw files made with it my jaw dropped. It remains fairly sharp all the way out to the edges, even wide open, although the Voigtlander Nokton is even better in the outer zones. Overall, it’s probably the best 50mm lens I’ve ever used. Like it’s brother the 35/1.4 it is very fast, compact, lightweight, sharp and has an absolutely beautiful way of rendering both in-focus and OOF areas. This is an all-around wonderful lens with a slight tendency to over-expose the highlights in contrasty light.

Voigtlander Nokton 50/1.5 ASPH – This lens is a bargain at $329.00 and joins the Voigtlander 35/2.5 (tested previously) as a superb value for the dollar choice. It’s nearly as sharp as the Leica 50/1.4 Aspherical and is dramatically less expensive. The drawing is also beautiful. This is one of the best 50mm lenses I’ve ever used, regardless of price – the fact that one can buy it for just $329.00 is just icing on the cake. I bought the test lens rather than send it back to CameraQuest and have used it extensively ever since. It may be the best inexpensive lens I’ve ever tested.

Canon 50/1.4 – This lens has less macro-contrast than the newer lenses but it comes close to their performance on center and does fairly well in the outer zones at most apertures. This lens seems tohave higher micro-contrast than the Canon 50/1.8 and, on a digital body in particular, is a great ‘sunny day’ alternative to the more modern, higher macro-contrast lenses. Like most of the Canon RF lenses I’ve tested, however, it isn’t able to focus as close as more modern lenses and I sometimes found this limitation to be frustrating.

Leica Noctilux– The Noctilux is a very special lens, not only for its F/1.0 speed but also for its distinct way of drawing which is both soft (in terms of focus) and contrasty at the same time. There can be a kind of lusciousness in pictures made with a Noctilux which is not easy to describe in words. For those who love it, there is no substitute. But the lens is large, very heavy and not easy to focus wide-open with consistent accuracy on the R-D1. As I mentioned earlier in this article, it also blocks a large portion of the finder, especially with its hood extended. Leica gave the lens a slow-ratio focus ring, no doubt to assist with precise focusing. But on the R-D1, I just found the focus ring ratio to be slow and awkward. In fact with quickly changing subject matter, I found the ratio of the Noctilux focus ring to be too slow to keep up with the primary subject. I would not choose to use the R-D1/Noctilux combination at large apertures for fast work in low light, but would use instead the 50/1.4 Summilux or the 50/1.5 Nokton. Though the latter two are a stop slower than the Noctilux, they allow me to focus accurately and quickly on the R-D1 and they’re much sharper, lighter and more compact. But they draw differently, to be sure. Not worse, just differently. I know of one widely-acclaimed photographer who has done much of his signature work with the Noctilux and various Leica bodies and it’s way of drawing has become part of his, quite distinct, photographic style. The lens clearly provides one example of why there can be more to a great lens than just sharpness. But as beautiful as its drawing is, I am not tempted to own one for the R-D1 because, while I sometimes love the results, I don’t love working with it while I’m making pictures.

__________________________________________________________________________

Conclusion

Early in this review I mentioned that one can’t fairly compare, in any strict sense, lenses with different maximum apertures. In general, the faster a lens is, the more challenging it becomes to correct aberrations. For this and other reasons, I won’t be ranking these lenses nor will I will declare winners and losers (although I imagine the reader may). Let’s assume, however, that a photographer is choosing among fast lenses either for use when working in low light or because of a desire to sometimes work with a very shallow depth of field. Defining “fast” is a somewhat arbitrary process and in this article I’ve defined it as F/2 or faster. What does one give up when going from an F/2 to an F/1.4 or F/1.5 lens? Looking at the best lenses in this group, I’d say…very little. If one is looking for the conventional virtues of high apparent sharpness and high micro-contrast then lenses such as the Leica 35/1.4 Summilux Aspherical, Leica 50/1.4 Summilux Aspherical, and Voigtlander 50/1.5 Nokton perform so well that one has little sense of having compromised quality at all for the one-stop increase in speed over an F/2.0 lens. It is true that an F/2.0 lens like the Zeiss 35/2.0 Biogon wide open seems sharper in the outer zones than a lens like the Leica 35/1.4 Aspherical at F/2.0 but then the latter lens seems sharper on center than the Zeiss. Which is better? It depends on how you want to draw. A lens like the Leica 50/2.0 Summicron seems very sharp both on center and in the outer zones but both the Leica 50/1.4 Summilux Aspherical, and Voigtlander 50/1.5 Nokton perform quite similarly in both areas. When one further considers that many of these F/1.4 ~ F/1.5 lenses are also reasonably lightweight and compact, there seem to be few reasons (other than cost perhaps) that a photographer looking for fast lenses would not give them serious consideration.

Beyond F/1.4 is a different matter altogether. The Nokton 35/1.2 is about a half-stop faster than the Leica 35/1.4 Aspherical but it is larger, heavier and blocks more of the finder than the Leica. It also does not seem to be as sharp, especially in the outer zones. For my work, these tradeoffs are not worth the extra 1/2 stop of lens speed. One cannot overlook the significant difference in price between the two, however, and that difference certainly argues in the Nokton’s favor. I’ve discussed the pros and the cons of the Leica 50/1.0 Noctilux already and it’s clear that this lens has certain advantages and, to be sure, certain disadvantages over the 50 Summilux and 50 Nokton.

It’s also possible that one may be looking for neither high apparent sharpness nor high micro-contrast in a lens. Or perhaps one wants a lens that has one of these qualities and not the other. Or perhaps one likes a lens to seem sharp on center and soft in the outer zones. And so on with other possible combinations… Every lens in this test could potentially be the right tool for a specific kind of picture-making. Contrary to what is often said and written, there are no absolute rules in photography and from time to time, truly original and strong photographers remind us of that. Consider the lenses presented in this review as making up a kind of virtual toolkit. Then reach in and pick your tools.

__________________________________________________________________________

Sean Reid, an American, has been a commercial and fine art photographer for over twenty years. He studied under Stephen Shore and Ben Lifson and met occasionally with Helen Levitt. In the late 1980s he worked as an exhibition printer for Wendy Ewald and other fine art photographers. In 1989, he was awarded an artist-in-residence grant from the Irish Arts Council in Dublin, Ireland. Hiscommercial workis primarily of architecture, weddings and special events. His personal work is primarily of people in public places. Having worked mostly with large format and rangefinder cameras for many years he now works primarily with Canon DSLRs and Epson R-D1s. Many of his newest reviews and other articles can be found athttp://www.reidreviews.com