On the fine art side of the equation, photography was coming into its own in the 70s. The elevation of photography to art form, comparable to older media, like painting and sculpture, was built on the impact photography had made on the printed page and that impact was cultural, broad-based, and international in scope. During my interviews, Mike Blumensaadt was the first to recount that his dream in the early 60s was to have a career as a working photographer, making a living with a camera. This was the goal of all the other photographers I talked to, as well. David Rae Morris stated he didn’t even think about museum exhibits or print sales until much later in his career—20 years later. Alex MacLean, who would go on to win the Rome Prize and is now represented by galleries internationally, wasn’t thinking of exhibits either. He was merely elated that after 4 years of waiting tables at night, and chasing freelance work during the day, he could finally give up the table waiting. No photographer in their right mind thought about a museum exhibit early in their career. That just wasn’t a common reality. There was no viable path to it. Mike began his career earlier than any of the other photographers I interviewed and when I asked him about what he knew of photography as an art form in the early 60s, he actually was aware of much of what there was to know at that time. He knew about Stieglitz’s New York gallery, 291, where photography was shown with contemporary drawing, watercolor, and painting. And he knew about Camera Work, the iconic photo magazine that Stieglitz published, which was far ahead of its time, pre-dating the large format picture magazines by several decades. Mike also knew about Steichen’s Family of Man exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. It was ground breaking for the 1950s. But, photographs wet mounted to masonite with radial corners, and hung salon style like a presentation at a sales convention, seem not just quaint by today’s standards, but disrespectful of the medium. I remember vividly at a gallery talk in the late 90s, Danny Lyon, who was in the Family of Man exhibit, telling about his lawsuit against MOMA, which resulted from the exhibit. When the exhibit came down, MOMA did not want to pay the extra postage required to return mounted work to the exhibiting photographers. So, his 8×10 print was peeled from the masonite and mailed back to him in a mailing tube. As one might expect, peeling a wet mounted print off masonite defied a non-reversible process, and the print was damaged. Lyon wrote to MOMA that his print had been damaged and he included an invoice for $25, which is the amount he charged for a gallery print at that time. MOMA wrote back that whereas they acknowledged damaging the print, they would not pay the elevated “art” price of the print, but could instead offer $1.75, which was the typical price charged by a NYC photo lab for a commercial b/w print of that size. Lyon subsequently sued MOMA in small claims court to get his money. This is good anecdotal evidence of what was thought of the value of a photographic print as a contemporary work of art, by one of the few museums in the country willing to exhibit the medium in the 1950s. By the 70s times would change.

The 70s became an epic decade for photography. The big picture magazines were still around, though they were actually dying. Television was killing them off. But, as all the ad men would be telling us in the 80s, “We’re keeping them alive with our liquor and cigarette ads.” Both products were banned from television advertising, but were permitted to continue advertising on the printed page. Even so, photography was evolving beyond the era of the picture magazines, making its way to coffee table books, gallery walls, and to major museum exhibits.

Photographic education had become a major force in this transition. Beginning with the post-World War II era, art schools and colleges with an art department, had been gradually accepting photography as a new medium and were adding it to the curriculum. This meant hiring instructors to teach it. The opportunities were substantial and since photography had not been taught in art schools or universities previously, the first instructors did not have to meet strict academic credentials. Edward Weston was hired to teach at San Francisco Art Institute in the 1950s though he only had a 9th grade education. Other instructors may have had college degrees, but not in photography since it wasn’t available yet. This would need to change and it did so quickly. Graduate degrees in photography became the rage by the late 60s and as fast as they could be churned out, MFA graduates were filling teaching positions all over the country. Photography instructors were in great demand by art departments just getting into the photography game. The demand was two fold. Photography was being added to the curriculum while college education, in general, was rapidly expanding. Baby boomers had reached college age by the late 60s and early 70s and a bigger percentage of them were attending college than any preceding generation of Americans. The prospect of teaching photography at the college level was a boom while it lasted. By the late 70s, most of the positions had been filled by youthful instructors, who have only begun to finally retire over the last few years. The last of the college age baby boomers finished up their college experiences by the 80s. As rapidly as it had begun, the phenomenon leveled off, and today those who want to teach photography full time find themselves in a fiercely competitive environment.

During the 70s photography appeared on the radar of the intelligentsia, art collectors, art writers, and artists working in other media. A compilation of essays Susan Sontag had written for New York Review of Books saw publication in 1973 by the prestigious New York publishing house Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Titled simply On Photography, it was a major hit and by 1977 was a Dell paperback and the recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. Beginning in the 60s and continuing to the 70s, photography critic A. D. Coleman’s reviews, most notably in the New York Times where he was their first photo critic, and also in the Village Voice, and the New York Observer, had a substantial following. Coleman also authored a number of photographic books beginning with The Grotesque in Photography in 1977. The year before he had been the first photography writer to receive an NEA fellowship. The critique of photography in prominent and respected publications, alongside the major exhibits and publications of more established art media, should not be underestimated. This was a necessary step before contemporary photography would be widely exhibited and collected. That was already happening in the 70s too. Sam Wagstaff, who came from a prominent New York family, was in the 1960s, curator of contemporary art at the Wadsworth Atheneum and later at the Detroit Institute of the Arts. He was, like his father before him, a notable collector. By the early 70s he had turned his eye to photography and began seriously collecting it. He was convinced that photography was unduly unrecognized and he began selling off his substantial collection of paintings to buy it. By 1984 he had amassed over 2500 19th and 20th century photographic works, which he sold to the Getty for $5 million, an unheard of sum for a photographic collection at that time. This purchase became the cornerstone of the Getty’s world class photography collection today. Ironically, Sam Wagstaff was as well-known in the pop culture of the late 80s as the partner of Robert Mapplethorpe, as for his recognition of photography as an art form worth investing in. Wagstaff died of complications of AIDS in 1987, two years before Mapplethorpe.

Just as significant as the criticism, collecting, publishing, and exhibiting, was the iconic status conveyed to photographers. When, in 1975, Walker Evans died, it was on the front page of the New York Times. Evans had a pantheon career. In the 1930s his photographs for the Farm Security Administration defined the Great Depression. When we remember that era now, those of us who didn’t live through it, know it through the lens of Evans, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee, Arthur Rothstein, and many others who chronicled it. The list is long, but Evans is at the top of it. Evans went on to co-author, with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. This classic about white tenant farmers in Alabama stands alongside Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath as an epic chronicle of the injustice and exploitation during a sad era of American history. The power in Evans photographs and Agee’s words have only intensified with time, as they have for Steinbeck. After becoming the first photographer to have a solo exhibit at MOMA in New York, Evans became the photo editor at Fortune, holding a helmsman’s position through the halcyon era of the big picture magazines from the mid-40s to the mid-60s. After that, he was old, but rather than sit around twiddling his thumbs in retirement, he directed the photo department at Yale School of Art. He did it all. If his obituary didn’t merit the front page of the Times, no one’s did. Then on September 3, 1979, near the end of the epic decade, a living photographer was on the cover of Time magazine. Ansel Adams, posing with his Linhof Technika, was photographed by David Hume Kennerly, who in 1972 had won the Pulitzer Prize for his photos of the Vietnam War. The caption beneath the portrait read, “The Master Eye.” Long before he made the cover of Time, Ansel Adams was a household name, as recognized as that of movie stars and major political figures. He was also a millionaire and his fortune had been made from his photographic art.

So ended the epic photographic decade of the 1970s. It’s gestalt would charge the 80s and even carry forward to the early 90s. Then as the 90s wound down and a new millennium approached, changes in both information and photographic technology converged to fundamentally change the medium of photography. There’s an ebb and flow in the evolution of all media. Photography is no exception. In the next segment, Photography Now, I’ll look at the period from the advent of digital photography to the present. From this background synopsis of the recent past it should be clear that progress has been made on many fronts. More galleries exhibit photography and represent photographers. Museum exhibitions of photographic works are common, rather than extremely rare, as they were in the 70s. Prints sell in greater quantity and for more than the equivalent of $25 or $50 too. But, has the progress been uniformly this positive on all fronts? I don’t think so, and that’s what segment two of this essay will attempt to clarify. In the meantime, I’ll close this segment with a few questions, which aren’t intended to be rhetorical: When’s the last time a photographer was on the cover of Time, or any other news weekly of similar readership and stature? When’s the last time you read a photographer’s obituary on the front page of the New York Times? When’s the last time a photographer was the lead character in a major art film from the likes of Antonioni? These events may not be the core matrix from which to assess the health of a profession, but they are indicators of how significant and prestigious the profession of photography is valued by the whole of society. They are measures of relevance, clout, influence. For me, the most important metric to explore in Photography Now is whether the profession is as relevant, prestigious, financially lucrative, or desirable, as it was in the 70s. And I want to examine that on both the commercial and fine art fronts.

Richard Sexton

Richard Sexton is a noted media and fine art photographer whose work has been widely published and exhibited. Many details about his career have been mentioned in this essay. More information can be found on his web site .

Many thanks to the photographers who were interviewed for this essay. More information about them and their work is available via the links below:

Mike Blumensaadt

www.matrixphotographics.com

Alex MacLean

http://www.alexmaclean.com

http://www.landslides.com

David Rae Morris

Website: http://www.davidraemorris.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/David-Rae-Morris-PhotographerFilmmaker-16730127345571

https://www.facebook.com/YazooRevisited

Twitter: @DavidRaeMorris

Myko

www.multistitch.com

www.mykophotography.com

www.mykophotography.com/commercial

Carter Tomassi

http://messyoptics.com

Richard Sexton

January 2016

You May Also Enjoy...

Travels with my camera

Travels With My Camera Introduction Back in the days when I was a photojournalist, traveling to do photography had its advantages. I had no weight

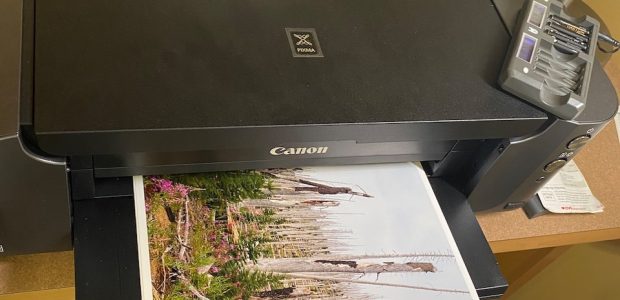

On Printing and Paper Part III – Printers.

FacebookTweet Making your own prints, especially using a large-format printer that can produce 16×24” and larger prints, is a substantial commitment in time, space and