By Charles S. Johnson, Jr

Science and art are products of the mind; they are of the mind yet they are the mind,Robert L. Solso

What people find beautiful is not arbitrary or random but has evolved over millions of years of hominid sensory, perceptual, and cognitive development, Michael S. Gazzaniga

Everything the visual system does is based on (such) educated guesswork,V. S. Ramachandran and S. Blakeslee

______________________________________________________________

1 – What is a good photograph?

To most casual camera users, photography provides documentation of people and events. It “saves” memories and is usually judged by its subject content. Did it capture a likeness, was there good timing, and so on? Family and friends glance at photographs and say “that is a good one” or maybe “I would like a copy.” When the photographer has better, more expensive, equipment there is a natural tendency to expect better photographs. When more is expected, there will be more disappointments. The photographer now wants good exposures, sharp images, and natural colors. These are technical requirements, and with some study and experience the photographer can learn what is possible with the available equipment.

At the next level we encounter amateur photographers who know about lenses, the importance of using tripods, and many technical details. They have researched cameras and have equipped themselves to make technically perfect images. Now the standards are higher and the photographer wants approval from more than family and friends. First, there are other photographers, who are potential competitors. Then there are camera clubs with photo competitions and experienced judges. This can be painful to the beginner because a judge might be unmoved by a favorite photograph or may dismiss a photograph out of hand because some rule of composition has been violated. Also, two judges may have very different reactions to the same photograph.

At this point the amateur photographer may simply reject photo competitions and enjoy his or her photography as it is. This is certainly a valid option and is the one chosen by most amateurs. But there are others who enjoy competition and who desire feedback from other photographers. Photography is a big thing for these individuals, and they are willing to devote a lot of time and money to improving their photographic skills. They read books, attend workshops, and go on photo shoots with the aim of learning how to make better photographs. They are serious amateurs and they may aspire to become professional photographers.

With the serious amateurs in mind, I return to the role of judges. Their work is certainly subjective, but observations of many judges over time reveal some consistency. (I am ignoring truly bad judges who exhibit unreasonable bias and a lack of expertise.) Some judges describe the informal guidelines they use and are willing to critique in detail images that they have judged. Here is a sample set of guidelines:

Technical perfection (exposure, color, critical sharpness)

Composition (pleasing layout, may involve conventional rules of composition)

Impact (eye catching, novel,etc.)

These points may be given weights such as Technical (30%), Composition (30%), and Impact (40%). What is clear is that the judge is dealing with visual art, and the process is essentially the same regardless of how the art was created. This is truer for photographic competitions now than ever before because of the widespread manipulation of digital images. Nature photography contests may impose restrictions, but some level of adjustment is usually permitted even there.

So the bottom line is that we are dealing with visual art, and judgments are subjective, but not completely so. There are rules of composition, but they are nothing more than lists of features that either appear in or are missing from images that appeal to experienced observers. For example, an object in the exact center of an image often makes a boring picture. A “rule” suggests that an object should be placed one third of the way from one edge, but there are many exceptions. I will return to lists of rules later, here I am concerned with more fundamental questions. What is art after all, and why are certain images appealing? These are the questions that I attempt to address, but by no means settle, in this essay.

Are the creation and appreciation of art valid topics for a science book? Absolutely! It is all about the brain. (In order to avoid confusion with terminology let me distinguish between brain and mind. The brain is a physical object and the mind is what goes on in the brain.) The real question is whether the neurosciences have advanced to the point that they can help us understand human creation and evaluation of visual art. This is an exciting area of research, and a lot of related work is going on. Neurological studies of the perception of color give us a glimpse of what is involved. A number of distinct areas of the brain work simultaneously on different aspects of a visual image, assigning color, detecting motion, recognizing faces,etc.; and by an unknown mechanism the conscious mind experiences and understands a consistent and even beautiful image.

This chapter turns out to be an introduction to visual perception and art. I have made use of numerous recent publications on cognition and art including Margaret Livingstone’s beautiful book,Vision and Art (2002). 1 Also, Robert L. Solso‚¬â„¢s books on cognition, art, and the conscious brain (1994, 2003) 2,3 and Semir Zeki’s book,Inner Vision4 deserve special mention. More recently, Michael S. Gazzaniga has addressed art and the human brain in his book,Human. 5 Of course, the bible of human visual perception is the wonderful book,Vision Science,by Stephen Palmer . 6 Finally, I note that this area of science has strong overlap with the exploding area of Computational Photography.7,8

______________________________________________________________

Art and Consciousness

So what is art? The definition of art is controversial since there is the danger that any definition will be too restrictive. That may be, but this is my provisional definition of visual art: Visual art is a human creation that causes pleasure, and by the aesthetic judgment of the human mind it is somehow beautiful or at least stimulating. If this is too general for the photographer, just think of two dimensional, framed images that contain either patterns or representations of the world. Other definitions of art will be stated or implied in later sections of this chapter, but I do not accept the idea that all art is bound to culture. I am concerned with more universal, cross cultural aspects of art. Also, my concept of art is closely connected with beauty, which indeed is universal. Steven Pinker points out that culture, fashion, and psychology of status (imparted by one’s judgment and also ownership of art) come into play in addition to the psychology of aesthetics when judging art. 9 I suspect that all of that is true, but I will attempt to focus on works that are aesthetically pleasing and instructive.

Art is conceived by the human mind and for the human mind. But why does our mind have this capability and inclination? It is reasonable to assume that the brain evolved for survival value, and sight evolved because of the knowledge it gives about the world. We can speculate that visual capabilities evolved because of particular needs. For example, color assignment and color constancy aid in the selection of ripe fruits. Solso emphasizes that the brain evolved to facilitate the primal functions: hunting, killing, eating, and having sex. 2,3 These activities are, of course, not limited to humans. The ability to create and appreciate art is uniquely human, and it may be just be a by-product of the evolution of the complex and adaptive human brain. 9 However, there are strong arguments that art plays a functional role in the development and organization of the brain, making humans more effective and more competitive in a variety of ways.

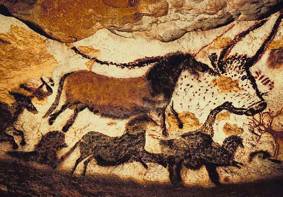

By 100,000 years ago the brain of homo sapiens reached more or less its modern capacity. Undoubtedly, people from that period and later produced decorations and carvings, but the earliest paintings that have been found date from about 35,000 BCE. These are cave paintings in the caves of southern France and in Italy. Among the oldest are those found in the Grotte Chauvet, which contains about 300 murals. Less well preserved, but possibly older, images have been found in the Fumane Cave northwest of Verona. 10,11 The Paleolithic paintings, mainly of animals, show depth and are executed in vivid colors. It was Solso’s thesis that the human brain evolved to the level of complexity and adaptability that supported a high level of consciousness (awareness) and that in turn enabled art, or conversely that art reveals for us the appearance of conscious minds in the Stone Age.

Figure 1: An example of murals from Lascaux, France. (c15000 BCE)

It all comes back to the capabilities of the human mind. We are blessed with a compact brain, that none the less, provides amazing power through multichannel/multiprocessing. This is computer talk which may be inappropriate. The brain is a machine that is doing some kind of information processing, but it may not be a computer. What we know is that it contains 100 billion neurons (nerve cells) and that each neuron is connected across synapses to as many as 100,000 other neurons. Furthermore, the connections are constantly changing in response to changing stimuli and the history of stimuli. Consequently, a mind will not respond exactly the same way to an identical stimulus the second time. Those in the Artificial Intelligence (AI) community, who hope to simulate the human mind, face a daunting task. 12

Consciousness is the feature of the mind most closely associated with art, but it is also the least understood feature. We can say a lot about the characteristics of consciousness; but we are far from understanding what it really is, and how it comes about. Consciousness is what makes us who we are. We wake up in the morning with a sense of self and experience external and internal sensations. Awareness is the essential feature of consciousness, and there is some level of consciousness even in our dream states. So consciousness is related to our global or overall mental situation where the storm of sensory stimuli have been suitably arranged, filtered, and averaged.

However, we know from neurological studies of brain damaged individuals and from functional imaging (MRI and positron emission) studies that the brain is organized in spatially defined modules. These modules respond to different aspects of the visual field that are mapped onto various venues of the brain. For example, the recognition of properly oriented faces is localized in the fusiform gyrus face area, and damage to this area results in prosopagnosia, the inability to recognize faces. The problem, we are faced with, is that the brain is subjected to a vast number of stimuli each second, and these stimuli are somehow processed in various locations; and yet the brain has learned how to select the essential elements and to present an understandable illusion of a three-dimensional world with colors, sounds, odors, tastes, and tactile sensations all appearing stable and natural to us. Furthermore, we can move and respond in “natural” ways in this self-centered awareness. So where does this blending and integration come from? No areas of the brain have been identified with the construction of consciousness, even though consciousness is modulated by many parts of the cerebral cortex.

Where does art fit in? One view is that art is an extension of what the conscious mind is doing for us. The mind selects essential features out of cacophony and chaos that can represent a consistent view of the world, though not necessarily objective reality. 13 We believe the mind “enjoys” understandable presentations and is disturbed by unresolved sensations. Things tailored to the capabilities of the brain attract rather than repel human beings. Similarly, effective art represents the product of millennia of experiments by artists to discover patterns and designs that stimulate the cortex. Rather than studying the structure of the brain in an attempt to discover the origin or art, artists and other experimental neurologists discover art by trial and error. The relevant structures in the brain are revealed by those compositions that are judged to be art. Feelings of joy and even euphoria are felt by the mind when “beautiful” human creations are experienced whether they be sculpture, paintings, music, or theories of the universe.

______________________________________________________________

How images are perceived

The problem here is to understand how images received by our visual system are processed to create the world we perceive. There are two stages of perception that I will consider separately. The first has to do with automatic, fast vision capture and processing. These are processes we share with other primates. Our eyes do not make very good images. They only have reasonable resolution in the center of the visual field; and this part must be projected onto the only area of the retina that has good resolving power, namely thefovea centralis. Our vision relies on a coordinated system of extraocular muscles to orient our eyes and to direct our focus on points of interest. In addition to these limitations, the amount of brain power that can be devoted to vision is not unlimited. It has long been realized that the 2-D images projected on our retinas do not alone contain enough information for the creation of the 3-D world we perceive. This is theinverse problemthat turns out to be indeterminate. Our visual system copes with these limitations by judicious choice of the scanning path for our eyes over the visual field coupled with perception aided byunconscious inductive inference. Here the scanning path refers to the sequence of focus points chosen to assess a scene. This overall process is known asBottom-Up-Awareness. 2,3,6

Think of built-in defaults; just as our computers can be programmed to recognize a few letters and jump ahead to a likely word, the brain interprets images with bias toward likely outcomes. For example, at first glance all objects are assumed to be viewed from the top and illuminated from above; and faces are quickly recognized if they have the proper orientation. Similarly, missing pieces are supplied to figures, ambiguous letters are interpreted according to context, and objects are grouped by proximity and similarity. We also get an immediate impression of depth. At close range this is based primarily on the slightly different images received by the two eyes (binocularity). There are also kinetic clues to distance as we move relative to objects in the visual field. Nearby objects appear to move much faster than distant objects in a way that enhances our sense of depth (motion parallax). A major part of this effect results from the changing occlusion of distant objects. Figure 2 illustrates our built-in assumption about lighting with a photograph of a package of pills from the pharmacy. The right and left sides are the same photograph with different orientations, and most people interpret the right side as bumps and the left side as pits.

Figure 2: A pill case photograph with two orientations.

For distant scenes and 2D representations, there are numerous (monocular) clues to depth. Our default islinear perspective where similar sized objects appear to decrease in size with increasing distance but still are perceived to maintain their size. This can lead to errors and illusions . Also, our natural orientation on the surface of the earth leads to the assumption that elevation is related to distance, and we note that children tend to place distant objects high in their drawings. Of course, even in 2D, distant objects are occluded by near objects and atmospheric effects on clarity and contrast often distinguish distant objects. Other subconscious clues come from shadows and even the orientations of shapes and forms. A few visual illusions based on clues for distance are shown in Fig. 3. 14

Figure 3: Visual illusions: (a) Converging straight lines appear to be parallel,

(b) Two horizontal lines (yellow) have the same length, and

(c) The red and black oblique lines are parallel.

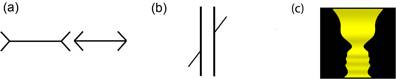

Still other illusions are not so easy to explain. In Fig. 4, I show the nineteenth century Müller-Lyer and Poggendorff illusions in parts (a) and (b), and a vase or faces construction in part (c). In part (a) the two lines are of equal length and the illusion of unequal lengths persists even when the arrow heads are replaced with circles or squares. In part (b) the oblique lines exactly match up regardless of how it appears. According to recent studies, both illusions can be explained on the basis of statistics of what the visual system has encountered in previous scenes. 15 Reactions to part (c) apparently depend on what the observer is prepared to see; except, of course, in cases where the viewer is familiar with the type of illusion. Readers can find numerous still and animated illusions online at Wikipedia and other sites. 16,17

Figure 4: More visual illusions: (a) Muller-Lyer, (b) Poggendorff, and (c)Vase or Faces.

Inference drives many of our perceptions and leads us to see or imagine familiar objects in shapes we see. Contours that appear to represent one thing but then shift to a different appearance when a different side is studied provide examples. Another set of illusions result from the fact that our visual system makes use of illuminance, or perceived brightness, rather than color in establishing position. For example objects that have a different color than the background but the same luminance may appear to have an unstable position.

In bottom-up processing, salient features of a scene receive immediate, focused attention orfixation,and the scan path of our vision quickly samples the image and returns to more interesting features for multiple hits. Studies of eye motion reveal that faces are high on the list of salient objects. Saccadic eye movements , which consist of angular jumps up to about 60 o each requiring 20 to 200 milliseconds, direct both eyes to a sequence of visual points. This generates a few high-resolution snapshots from foveal vision per second while the data from fuzzy peripheral vision is simultaneously received at much higher data rates. It is believed that this unbiased behavior of the visual system provides more or less the same impression of a scene to all observers.

The second stage of visual perception involves intentional direction of vision,i.e.volition. Here the “searchlight” of attention is brought to bear on features according to personalschemata. This is known asTop-Down-Awareness. Schemata are essentially schemes for organizing knowledge based on what is important to an individual. Training, background, and even role playing can affect the sampling and analysis of an image. This implies a “mind set” that can lead to increased efficiency but also automatic, “knee jerk,” assessments. At its worst, this can result in rigidity and reluctance to accept change, the opposite of open-mindedness. For example, we see schemata in fads that dictate what styles are “in” during some historical period. Schemata are not only locked in by experience or inclination, they may exist temporarily because of a recent work experience or even a role playing exercise. For example, you might be asked to assume that you are a policeman while viewing a scene.

In viewing a work of art, the initial visual scan (bottom-up awareness) may emphasize faces and other salient features to provide a first impression. The immediate impact of the work may result from bright colors or perhaps novel features. In the second stage (top-down awareness), the observer can bring to bear education, experience, and training to evaluate the work in context. At this point discussion with others and additional observation may grossly affect the assessment of the observer, and personal schemata may be modified or strengthened. Art judges, of course, like all of us have sets of schemata in place. In a given period most of the judges may have similar schemata, and that poses a problem for new styles. There is also the schema of the jaded judge who is tired of images of sunrises, sunsets, hot air balloons, blurred water, and so on.

______________________________________________________________

4. Conclusions

I have tried to confront the question of why composition matters in photography and other visual art. The evidence indicates that art is closely related to and maybe inseparable from consciousness. We have seen that the organization of the human mind to permit awareness, taking advantage of the full capabilities of our senses, requires decades. Our imagination, including all forms of art, certainly aids in the organization process. The result of this process is the mature mind that experiences pleasure and even exhilaration at suitably arranged representations of the world. We describe such arrangements as art and are especially delighted when such representations expand our understanding through thought provoking novelty.

Our enjoyment in this colorful 3-dimensional world is tempered by the knowledge that our conscious world is an illusion. The illusion replaces the flood of stimuli from our senses with a calm, stable world view. Furthermore, our conscious state attempts to minimize our visual defects and to fill in unknown parts, such as blind spots, by sophisticated guesswork. This is, of course, the source of so called visual illusions. As observers of art we are limited, both by the universal Bottom-Up-Awareness and by our own unique Top-Down-Awareness. InPart III extend these ideas to the question of why images attract or repel observers. I will end with the practical consideration of how photographers might use their knowledge of visual illusions to make more interesting images.

______________________________________________________________

Notes

1. Livingstone, M.Vision and Art(H. N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 2002).

2. Solso, R. L,Cognition and the Visual Arts(MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1994).

3. Solso, R. L,The Psychology of Art and the Foundation of the Conscious Brain(MIT Press, Cambrdge, MA, 2003).

4. Zeki, S.,Inner Vision, An Exploration of Art and the Brain(Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1999).

5. Gazzaniga, M. S.,Human, (HarperCollins Pub., New York, 2008).

6. Palmer, S. E.,Vision Science(MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1999).

7. Hayes, B., “Computational Photography”American Scientist 96, 94-98 (2008).

8. Efros, A., “Computational Photography‚¬ Carnegie Mellon University: http://graphics.cs.cmu.edu/courses/15-463/2007_fall/463.html

9. Pinker, S., “How Much Art Can the Human Brain Take?” Adapted fromHow the Mind Works(Penguin paperback, 1999).

10. Balter, M. “Paintings in Italian Cave May Be Oldest Yet”Science, 290, 419-421 (2000).

11. Balter, M. “Going Deeper into the Grotte Chauvet”Science, 321, 904-905 (2008).

12. Koch, C. and Tononi, T., “Can Machines be Conscious?”,IEEE Spectrum, 45, 55-59 (2008).

13. Ramachandran, V. S. and Blakeslee, S.Phantoms in the Brain(Fourth Estate, London, 1998).

14. Zakia, R. D.,Perception and Imaging(Focal Press, Boston, 2002).

15. Howe, C. and Purves, D., “The Muller-Lyer Illusion Explained by the Statistics of Image-source Relationships”Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA102, 1234-1239 (2008);ibid.102, 7707-7712 (2008).

16. Optical illusions: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Optical_illusion

17. Bach, M., “78 Optical Illusions and Visual Phenomena”http://www.michaelbach.de/ot/

Excerpted fromScience for the Curious Photographer.

©2009 Charles Sidney Johnson, Jr.

Charles S. Johnson, Jr. taught physical chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana, Yale University, and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he held the title of Smith Professor of Chemistry. He has published approximately 150 papers on magnetic resonance and laser light scattering as well as books on laser light scattering and quantum mechanics.

His interest in photography goes back to the 1950’s; however, for many years his career in science left little time for serious photography. Now he is making use of his scientific background to research and write about the physical and psychological bases of photography. His recent book,Science for the Curious Photographer, includes discussions of light and optics, sensors, and the human visual system. In addition, it provides an introduction to human perception of color, appreciation of art, and cognitive limitations. The table of contents and additional excerpts from this book can be found at photophys.com. Arrangements for hardcopy publication have not yet been completed

June – 2009

You May Also Enjoy...

Workers – Chittagong

Please use your browser'sBACKbutton to return to the page that brought you here.