“In the electronic age, I am sure that scanning techniques will be developed to achieve prints of extraordinary subtlety from the original negative scores. If I could return in twenty years or so I would hope to see astounding interpretations of my most expressive images. It is true no one could print my negatives as I did, but they might well get more out of them by electronic means. Image quality is not the product of a machine but of the person who directs the machine, and there are no limits to imagination and expression.”

Ansel Adams, An Autobiography, 1985.

The last two decades have witnessed the emergence and spread of the digital revolution into virtually all aspects of our modern life. Nowhere has digital technology had a greater and profound impact (and controversy) than in the world of photography. I am reminded of the popular ad for a brand of cassette tape. The viewer was invited to decide whether the glass shattered by the piercing high note of a soprano was her live voice or her voice recorded on this brand of tape. The slogan was: “Is it live, or is it Memorex?” In this digital age a new question has presented itself: “Is it real, or is it Photoshop?”

While it appears to me that most photographers in all realms of endeavor have largely embraced the extraordinary advances in photography made possible by digital technology, there exists, nevertheless, a segment of fine art photographers, both black and white and color, that openly vilify and denigrate those photographers and their work, who use this new technology. It seems, in their opinion, that because of the extraordinary capabilities that digital technology offers for virtual total control over the photographic image, that all images produced in the digital realm, are not real, they are not “truthful”, they are morally and ethically suspect by their very “digital nature”. Fundamental to their objection is the absurd notion that because photography began and developed as a photochemical process that it absolutely defines the medium. That is as absurd as claiming that the horse and buggy defines transportation. As a photographer who has engaged in his work for over thirty years, in both black and white and color, and has now entered this arena of the “digital darkroom”, I feel compelled to weigh in on the issue.

The essential objection of the anti-digitites (as I shall call them) to digital manipulation in Photoshop and output to digital print is that the image or landscape depicted is not real, is not “really the way it was“. They claim the photographer has manipulated the image to the point where it bears little resemblance to the actual scene. One prominent Bibachrome printer states that digital prints have no “veracity”, or truth, to them, because they are not printed the old-fashioned way, dunked in a bath of organic chemicals, where apparently “photographic truth” resides. This claim is made by both color and black and white photographers alike. Somehow, they hold their chemical darkroom as a sacred temple, casting out from their midst those who would seek out greater possibilities for visual artistic expression using a different medium.

It is difficult for me to understand their issue about “the truth”. What does that mean? Whose truth? Is there some sort of absolute photographic truth that they have been anointed with? Fine art landscape photography has absolutely nothing to do with “truth”. Fine art landscape photography is about personal visual expression, and, most importantly, personal interpretation. It is not about some agreed upon absolute truth. There is nothing fundamentally real about landscape photography. Two photographers standing at the same place at the same time will not see and experience it in exactly the same way. Therefore, why would anyone expect, indeed demand, that their two images of the same scene should be precisely the same, should portray some “absolute visual truth”, whatever that is. The only real truth here is that the minute the photographer trips the shutter, packs up his gear and leaves the scene, the abject “truth” or absolute reality of that wholly unique place in time no longer exists. Further, the only remnant of that experience is that two-dimensional piece of film, which is nothing more than an abstract formation of light, dark, and/or color. A photographic image is a two dimensional abstraction of three-dimensional reality. There are no sounds or smells or physical sensations in a sheet of photographic paper with ink or chemical patterns on them. A photographic image by its very nature is not real; it is an abstract, selective interpretation by the photographer who took the image. It is only later, in the darkroom or at the computer screen, that the photographer sets about to manipulate and shape the abstract elements captured on that film in such a way to effectively visually express the experience of capturing that image and the emotional response it elicited.

If one looks at any of Ansel Adams extraordinary works, there is little about them that are “real”. I would be willing to bet that he would wholeheartedly agree. They are stunning and expressive precisely because they are interpretive. The drama of light and dark in many of his images are greatly enhanced (even exaggerated) through his masterful manipulation of the exposure, the development of the negative, and the creation of the final print. In fact, if one looks at the deep shades of black sky in many of his most dramatic landscapes, one would have to hit the saturate blue selection in Photoshop at +20 to get that degree of dark tone. Ansel Adams chose black and white not only because he could have such great control over the medium, but because with that control he could effectively express and convey visually what he felt and experienced when he released the shutter. The much-revered Adams was the absolute master of manipulation. As he expressed in the quote above, Adams noted in many of his later writings the great possibilities of visual expression and total control of the color image with digital technology. He lamented that it was too late in his career for him to be able to take advantage of digital capabilities, as he long wished for the opportunity to explore his photographic talents in the color realm.

It is indeed ironic that many of the anti-digitites revere and try to emulate Ansel Adams and his approach both in the field and in the darkroom. What is, unfortunately, untruthful about this whole issue is that they use in the chemical darkroom every conceivable type of negative and print manipulation that exists. They manipulate tonal control, edge contrast, color shifting, change color densities, dodge and burn, etc., on the one hand, and, criticize those in the digital realm for doing exactly the same thing. The big difference, however, is that we do it in much less time, with greater precision, greater potential for visual expression, and all without harmful, noxious chemicals. In, fact, Adams openly acknowledged that in his darkroom, he removed the letters “L.P.” from a hillside in the foreground of his famous final print of the Sierras, shot over the town of Lone Pine, California. Was that not untruthful manipulation? I have never once heard any Ansel Adam’s protégé’ complain about this “untruthful” darkroom manipulation. They only seem to cry foul when manipulations are done digitally.

It is true that with Photoshop one can create all sorts of visual realities that don’t truly exist. This is often done in the advertising and editorial photographic arenas for effect and drama. However, that does not condemn in any way the use of digital means in something like landscape photography, implying that everything produced in the digital realm is not fundamentally based in reality or real experience. It is simply how one uses the technology, in short, one’s photographic style (as I shall further elaborate upon). Photoshop can be used in exactly the same way to render a landscape image in a straightforward and realistic way as the chemical printers so proudly claim to do. It is quite apparent that with this new technology a photographer can have so much greater control over the image, produce a better, more archival print, and do it in considerably less time. Gone are the hours, days, and weeks, that a traditional chemical printer would sacrifice for but a few prints.

There is an uncomfortable feeling here for the chemical printer that the “pure artistic process of the chemical lab”, and indeed, the “purity” of the art itself, is somehow cheapened by a new process that is so much more efficient and precise. The belief here is that only those images that are labored over for days and weeks have photographic merit, and therefore must be photographically and morally superior because they took so long to produce. That is self-delusional nonsense. The simple truth of the matter is that chemical printers by nature of their media and its process must labor with an imprecise and antiquated method to achieve the final print. It is not how long one labors to produce a print; it is only the quality of content and visual expression of the image that matters. The digital revolution has simply rendered the chemical darkroom and its processes as a highly inefficient and now an outdated relic of the past. And once again, I believe that if Ansel Adams were alive today, he would agree.

The chemical printers remind me a little of the horse and buggy driver, mud splashed on his face from a passing Model A car, shaking his fist in despair and anger at this evil new creation he despises. The issue is not about “truth”, for truth is in the eye of the beholder, and each of us sees the truth in our own distinct way. The issue, the only issue, is as it has always been, and always will be is an artistic issue, an issue about personal vision and expression. To me, “the medium is not the message”. The medium is not the art in and of itself, though many chemical printers seem to believe that. The medium is only the path. What path one may choose to arrive at that finished expression of the photographic print is not nearly as important as the quality and substance of the expression of that photographic print. And with digital technology, an exciting and extraordinary new path has been created.

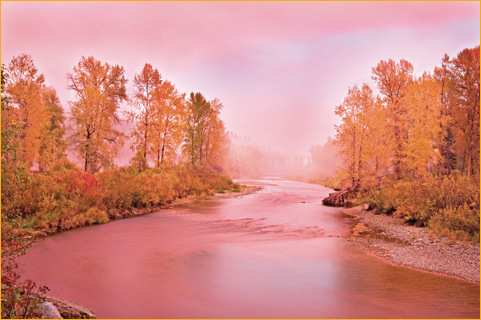

I cannot, however complete this essay without discussing one more extremely important point. As much as digital photography has its many advantages over traditional photography it has at least one disadvantage and a distinct challenge that I shall describe here as illustrated by a recent shooting. I was photographing late on autumn day on the Coeur D’Alene River in Northern Idaho. It was in the fleeting moments of sunset along the river, the last rays of sunlight, filtered and diffused by the fog and the clouds, cast an eerie quality of light on the landscape so intense and dramatically surreal, that I could literally feel it in my body. As I quickly set up my camera along the riverbank to capture this extraordinary moment, a rather emotionally deflating thought emerged, who is going to believe that the incredible colors in this picture are actually real? This is, after all, the age of Photoshop. I have always stayed away from colored filters for just this reason. Colors like this can and do occur naturally in nature and I endeavor to represent my photography as capturing those places and moments in time that reveal colors that are as rare as they are magically beautiful. Of course, various filters have always been used in color film photography for a variety of effects. However, because Photoshop possesses such enormous capabilities in dealing with color, far beyond what a simple screw on filter can do, unusual or extraordinary color that one might capture in a landscape is almost immediately suspect as a Photoshop enhancement. To be sure, it can be used to create or significantly alter almost any color palette in an image. It is also true, however, that color can be greatly exaggerated or altered in the traditional chemical process, so in a general sense, the same issue is still there in both realms; its just that as in all things digital versus chemical, Photoshop can simply do it far better.

I have considered this issue for some time now, trying to formulate an artistic and philosophical construct within which to faithfully represent the presentation of my vision and thus my use of Photoshop to create the final image. I’m happy to say that I have finally arrived at a very simple and uncomplicated conclusion; it is matter of personal artistic vision expressed in a photographic style. Photographers, who have arrived at that point of creating a discernable photographic style, become known and recognized for that style as such; it is a personal signature of sorts. Some photographers prefer intensely saturated colors in their images, and thus as you look at their body of work, brilliant, vibrant colors are the expressions of their personal vision and hence become their discernable style. The renowned photographer, Pete Turner, is just such an example. His style is marked by a wonderful abstract quality in large part derived by his use of intensely rich colors and hues. While some of my imagery displays rich and intense colors from time to time, it is simply because the subject matter contained them. I do not try to create rich and saturated colors in all subject matter, when it is not present, simply by creating it in Photoshop. Further, if one looks at the body of my work, it is apparent that my work tends to be dominated by subject matter that largely possesses off primary color hues. I am most drawn to subject matter that has a wide range of subtle hues and tonal gradations, which is why I most often shoot on overcast or subdued sunlight days. Thus, in the final analysis in regards to my work and to what extent I utilize Photoshop to manipulate color in the final image, the answer is found by viewing by the body of my work; my images are rich and saturated in color when the subject possessed them, and the colors in my images are muted and tones are gradated, when the subject and the light upon it presented such resulting colors to my eyes. In summary, by knowing and understanding a particular photographer’s vision and resulting style, one is allowed a greater opportunity to “pull back the curtain” on the technical and creative process that this artist chooses to employ in the creation of their work. And thereby, in doing so, hopefully gain a greater appreciation of the art of the photographic process such that they in turn may improve their own photographic skills in rendering the final print.

November, 2011

Bruce Heinemann is a fine art nature photographer in Anacortes, Washington, specializing in custom branded corporate print material. He has also published eight fine art coffee table books, two of which; The Nature of Wisdom and The Art of Nature: Reflections on the Grand Design Revised Edition were co-published with and are currently in all Barnes and Noble stores. http://theartofnature.photoshelter.com/

You May Also Enjoy...

Blue Hour in a Zen Meditation Forest

FacebookTweet Blue Hour in a Zen meditation forest with camera in hand at the base of Mt. Fuji, and I was awoken out of my