One of the most innovative camera and lens makers in Japan isCosina. It could be that over the years you have owned and used cameras and lenses made by Cosina, but you might not know it as they have primarily been a OEM manufacturer, producing products to be sold under other brands.

But in the late ’90s Cosina acquired the venerable Voigtlander brand name and began producing film and digital cameras, and lenses under that brand. Of particular interest have been their lenses, produced in Leica screw and M mount. These lenses have offered Leica users a very attractive range of quality optics at very reasonable prices.

In late 2010 Cosina announced that they had joined the Four Thirds consortium (the major players being Olympus and Panasonic) and that they would begin producing lenses in the Micro Four Thirds format. And though Cosina has never been a timid company, producing some of the most innovative and extreme lens designs, that their first M43 lens would be a 25mm f/0.95 was a bit of a pleasant shocker.

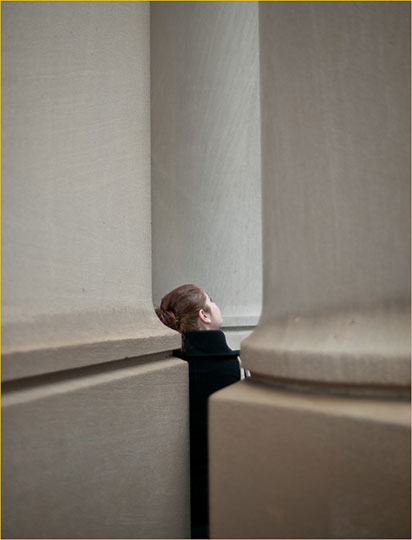

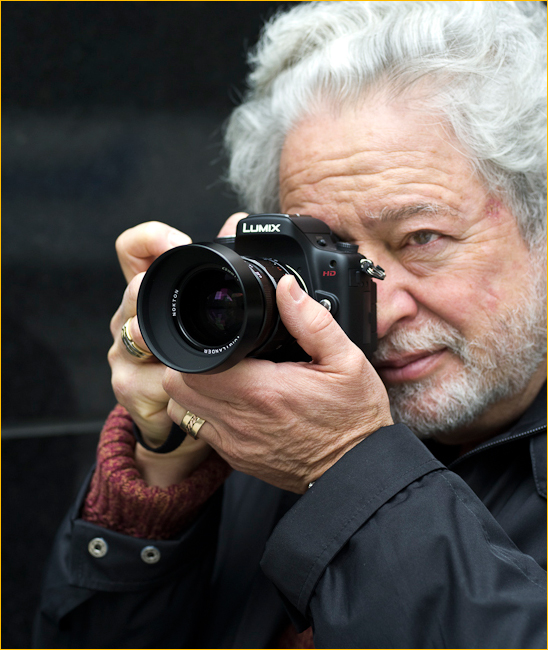

MR with Nokton f/0.95 mounted on a Panasonic GH1

Photo by Nick Devlin taken with Pentax 645D

f/0.95

While there are a few faster lenses, used primarily in surveillance systems, and also now obsolete 16mm motion picture cameras, one doesn’t come across lenses this fast all that often. Indeed the only mainstream photographic lens that’s this fast at the moment is theLeica 50mm f/0.95 Noctilux. This lens costs some USD $11,000 and while it is quite spectacular, it is not exactly something that is going to find its way into most people’s camera bags. Not only is it crazy fast, it’s crazy expensive and quite large and heavy.

On the other hand the f/0.95 Voigtlander Nokton (I purchased mine fromCameraquest ) is priced at around USD $900, and thus less than 1/10th the price of the Noctilux. It is 25mm, and in Micro Four Thirds mount, rather than 50mm in Leica M mount. Since 25mm in MFT provides the same coverage as 50mm in full frame 35mm terms, they are also equivalent in that respect. There are quite a few MFT cameras from Panasonic and Olympus that can take the new Nokton. You could, of course, mount the Leica Noctilux on an MFT body, using an available Leica M to MFT adaptor, but it will be a moderate telephoto rather than a “normal” focal length when used on MFT, and not only is it very expensive, it’s huge on an MFT body.

The 0.95 Nokton, though in native MFT mount, is also a fully manual lens. There is no autofocus and no electrical contacts, either for aperture control or even EXIF data transfer. You’re on your own when it comes to setting the aperture and focusing.

So – how fast is f/0.95? Obviously, it’s a bit more than one stop faster than what most of us consider the fastest typical prime lens at f/1.4. But other than full frame 50mm f/1.4 lenses there are few that fast at other focal lengths. Some camera makers have 35mm f/1.4 lenses, which on APS-C sized reduced-frame cameras provide a “normal” focal length, but these are also typically expensive lenses from each maker’s premium lines.

Columns. Toronto, November, 2010

Panasonic GH1 with 25mm Nokton f/0.95 at f/0.95 and ISO 100

More to the point is that most non-professional photographers are used to dealing with prime lenses not much faster than f/2 or f/2.5, and with zooms in the f/3.5 and slower range. An f/0.95 lens is more than two stops faster than an f/2 and some three to four stops faster than typical zooms. This means being able to shoot in low light at an ISO significantly slower than otherwise possible, or in light levels that would leave someone using a slower lens forced to impractically slow shutter speeds and thus blurred images.

The other benefit of an f/0.95 lens is its shallow depth of field, especially on a smaller sensor such as Micro Four Thirds. The smaller the sensor the greater the DOF for any given image magnification size. To have comparable narrow depth of field to a larger format, a small format needs to have a wider aperture.

Assuming that shallow DOF is what one wants for creative effect, a lens this fast is highly desirable. MFT is one quarter the size of full-frame 35mm in the stills world. This means that those shooting narrative video with this lens on a MFT camera like the Panasonic GH1 or new GH2, (or AH100) will feel at home with the DOF since it isn’t that much less than 35mm motion picture format. Stills shooters coming from 35mm format sometimes find the greater DOF of MFT advantageous, but sometimes not, and the Nokton will therefore provide the shallowest DOF possible on this format for any given subject magnification.

Build Quality

If all you’ve ever owned and used are contemporary lenses from the majors, such as Canon and Nikon, you’ll be in for a treat when you first pick up the f/0.95 Nokton. This lens isold school, and I mean that in the most complimentary way. I’m not just referring to its technical features (or their lack) either.

As someone with a life-long passion for Leica optics, picking up the Nokton for the first time was for me very much like handling one of Leica or Zeiss’ products. Indeed, Cosina makes many current lenses for Carl Zeiss, so this isn’t at all surprising.

The focusing mount is silky smooth, yet with enough resistance so that once set it isn’t going to too easily move off point. Aperture click stops are discrete and positive and the setting ring has no slip whatsoever. Simply put, this is a $900 lens that could easily go to a masked ball as a $3,000 Leica product, at least when it comes to visible and tactile fit and finish. In recent years Cosina has been continuously sharpening its game, and with the new f/0.95 Noctor they appear to have moved into a small class of companies that still know how and are willing to make lenses the old fashioned way.

Of course a lot of this has to do with the fact that there is no need for light weight mechanisms amenable to autofocus. Only Leica seems to have figured out how to marry traditional quality and precision in an AF lens, with those for the S2, but then these lenses are all north of US $5000, and this in a different league than mass produced lenses from Asia.

When it comes to the Nokton not only are there no light weight focusing mechanisms, there are no AF motors, no auto aperture stop-down levers, and no electrical wiring, or contacts, or chips. Other than its computer designed optical formula there is nothing about this lens that says 2010, let alone 1990, or 1970 or even 1950. Like I said –old school.

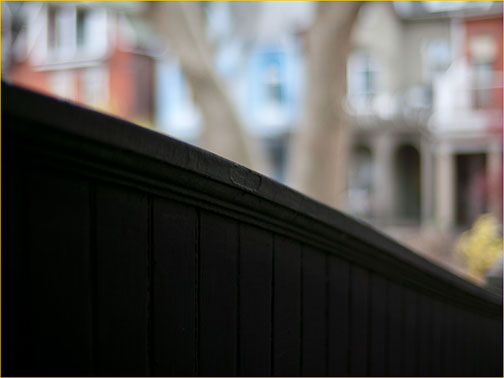

WOOF (Way Out of Focus). Toronto, November, 2010

Panasonic GH1 with 25mm Nokton at f/0.95 and ISO 100

The Nokton also pleases when it comes to its included lens hood and caps. Yes, caps – plural. The large lens shade is of metal construction and screws in. Given that large aperture lenses tend to flare, a substantial lens shade is most welcome. There is a standard snap-on style lens cap, but also a second one that pressure fits over the end of the lens shade so that one can leave it installed all the time, which is my preference. Nicely done.

The Issue of Focusing

Unless you own an M Leica or technical medium format camera you probably have become reliant on autofocus. That’s not an indictment or any sort. Most photographers have, and rightly so, because in theory AF can be superior to the human eye in terms of accuracy. (This was proven to most people’s satisfaction many years ago in a series of lab and field tests by Popular Photography magazine.)

But accuracy is one thing, and focusing on the right subject is another. All too often photographers set their cameras to multi-point AF, leave activation linked to the shutter release, and shoot away. Well, sometimes this is OK, but how many times have you looked at your files and wondered why things aren’t as sharp and in-focus as they should be?

The reason is simple. The camera automatically and very accurately focused onsomething– just not necessarily on what you wanted. That’s why when I teach field workshops, I strongly suggest that students set their cameras to single center point AF, and decouple autofocus from the shutter release, instead putting it on a button. Center the subject, press to lock focus, and recompose.

When using the Nokton an a MFT camera none of this works! AF doesn’t exist and there’s no focus lock capability. You focus by eye on the screen, and especially by using the live view image’s magnify capability of the camera.

So why do I mention all of this? Because it takes about the same amount of time and effort to focus the Nokton on an MFT camera as it does to use AF technology properly.

All MFT cameras have an on-screen focus magnify capability and critical focus can easy be achieved. What I found myself doing in fluid shooting situations is to roughly frame up the shot and then to go to magnify mode. With the camera to my eye (this works much easier with a model that has an EVF), I ride the focus ring until the moment that I want and then take the shot. By not returning to normal magnification mode first I am assured that the subject stays in focus. It works similarly to how one would shoot with a Leica M rangefinder camera when concentrating on the coincident rangefinder.

Close Focusing

Panasonic GH1 with 25mm Nokton @ f/0.95

One of the very pleasant surprises from the Nokton is that it focusing extremely closely, almost to the macro range. Combine this close focusing ability with the ultra-shallow DOF when used at f/0.95 and you have an exciting new creative tool that can turn even mundane subjects into art.

Panasonic GH1 with 25mm Nokton @ f/0.95

Subjective Evaluation

I have no charts and graphs or even brick walls to share with you. That’s not how I evaluate lenses for my own purposes, and so I won’t be doing it for you either. A few days of real-world shooting is all that’s needed to tell me what I want to know.

100% partial enlargement of frame seen higher up the page

Let’s start with the question of resolution, especially wide open at f/0.95. Above is a 100% crop of a small section of the image seen closer to top of this page. It was taken wide open, and as can be seen, even at 100% resolution is more than acceptable. Indeed on a 13X19″ print its positively crisp.

Of course this is at the center of the frame, and the extreemely shallow DOF masks any resolution issues at the corners and sides, so let’s look at that next.

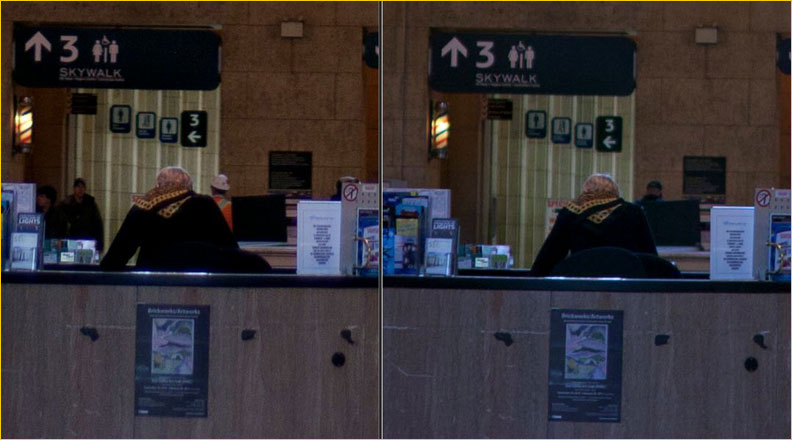

Union Station – Toronto

Immediately above is a shot of the main concourse at Union Station in Toronto. It and each of the examples below were taken with a Panasonic GH1 mounted on a tripod. Two lenses were used, the Voigtlander 25mm f/0.95 and the Panasonic / Leica 25mm f/1.4 Summilux. The Summilux wastested by Popular Photographyback in 2008 and was rated as “having excellent resolution“.

Nokton f/1.4 / Summilux f/1.4

The frames immediately above were both taken at f/1.4. The Voigtlander is on the left and the Summilux is on the right. What I see is a bit more contrast from the Voigtlander and a tad more detail. Very close, but with a slight edge to the Nokton.

Additional shots taken at smaller apertures show that both lenses sharpen up comparably, and any vignetting (as with almost all lenses there is some at wider apertures) disappears.

Nokton @ f/0.95

The above shot at f/0.95 with the Nokton is surprising in that it gives up little in the way of resolution to the next smaller aperture. Indeed in every shot that I took with the Nokton wide open I unfailing was impressed with its ability to not let me down and turn into glowing mush.

Speaking of glowing, that’s one aspect of the test above that you can’t see from the crops shown. Below is the part of the sign above the area in these samples.

Nokton @ f/0.95

If your shots have any light sources, like all ultra-fast lenses the Nokton will show some considerable glow. It’s still there at f/1.4, though greatly diminished, and it disappears completely at any smaller aperture.

Whether this is an issue for your photography will greatly depend on your personal esthetic. I find this to be part of the lens’ character and is very similar to the “glow” seen on images from the original Leica f/1 Noctilux, much sought after by collectors.

100% Crop. Nokton @ f/0.95

Immediately above is another example, this one showing howbadthe “glow” can be – or howgood, depending on your point of view. Indeed this is coma, not “glow”.

But, be aware that this is the worst example that I could find as I was searching for subjects that would show optical aberrations when used at f/0.95. Not all point light sources show this much, but be aware that it’s characteristic of this lens (and almost all other ultra-fast optics) that you’ll either learn to love, or will hate. And again – be aware that by about f/1.8 this lens becomes on a par in every respect with any other top lens of this focal length.

Parenthetically – if you want an f/0.95 lens that doesn’t glow, the newLeica 50mm Noctilux f/0.95is your ticket – at a mere US $11,000.

Other Fast Lenses

What is it about fast lenses that fascinates and attracts photographers? Is it the large expanse of multi-coloured glass, the feeling of exclusivity, the ultra-shallow depth of field when used wide open, or, of course, the ability to shoot in very low light conditions without resorting to noisy high-ISO settings?

Of course over the past decade we’ve gone from the words “fast and reasonably clean”meaning ISO 400, to meaning ISO 3200. “Fast but noisy”used to mean ISO 1200,while now it means as high as ISO 50,000+.

Putting aside the debate as to the preference for fast lenses or high ISO (or both), there’s no doubt that there are legions of photographers who appreciate the value of ultra-fast lenses in producing striking images.

If you own a rangefinder camera that takes Leica mount lenses then you should have a look at the Voigtlander Nokton 50mm f/1.1 , reviewed here by Nick Devlin, and for a historical perspective my50mm f/1.0 Noctiluxreview from about eight years ago.

There is one other ultra-fast lens, the50mm f/0.95 Noctor, which was announced earlier this year, but which has been shown asOut of Stocksince introduction. There was one online review, but the lens seems to have sunk beneath the waves since.

Conclusion

If you’ve gotten the impression that I really like the Voigtlander Nokton f/0.95, you’re right. It creates a quite unique way of viewing and recording the world that can really get one’s creative juices going.

At f/1.8 and slower the Nokton performs comparably to any other lens of similar focal length. But, because it lacks autofocus a great many photographers will find its use as a day-to-day lens somewhat frustrating.

But if you enjoy the creative capabilities that a shallow depth of field, ultra fast lens offers, and have an appreciation for old-school mechanical focus lenses with aperture rings that insist that you become involved in the technical aspects of photography, then I can’t think of too many other lenses that offer as much fun and creative scope as the 25mm Nokton f/0.95. And about $1,000, it’s a relative bargain.

Now your only problem will be to find one, as I understand that the first production run has pretty much immediately sold out.

November, 2010

You May Also Enjoy...

Leica X1 First Impressions

IntroductionIn mid-August, 2009, I was invited to join a small group of journalist on a visit with Leica at their headquarters in Solms, Germany. The

Noise Ninja Review

Delivering a Karate Chop to Digital Noise Every now and then a new product comes along that redefines expectations. In software-based noise reduction such a