The K-1000 of Digital SLRs

Good morning! I send wishes for good health and good fortune to everyone in the New Year. Unfortunately, however, the arrival of 2005 is clouded by a tragedy of almost unimaginable magnitude–the tsunami in the Indian Ocean. For the month of January, I’ll be scrounging around the house for things to sell on eBay so I can contribute at least something to the relief effort, and 25% of all "37th Frame" newsletter subscriptions and renewals will be donated to a Wisconsin company that is providing water purification pills to the affected areas. I send my thoughts, concern, and condolences to people in those parts of the world.

On a brighter note, I’m pleased to announce that beginning in early 2005, "The Sunday Morning Photographer" will be translated into Hungarian and posted on www.fototipp.hu. Incidentally, if you know of any large French or Italian photography websites that you think would make good venues for SMP in translation, I hope you will please propose it to them. All they need is a translator with the patience of Job, the work ethic of Sisyphus, and the strength of Hercules. (Well, no, actually they don’t need the strength of Hercules.) But enough of that. On to photography.

Pentax is an old photo-dog’s camera company. By "photo-dogs" I mean guys (and a few gals) with Dektol in their veins, darkrooms in the basement, and lenses they inherited from their fathers. As such, Pentax is something of a sleeper (if not a secret) among makers of SLRs, and perhaps an acquired taste.

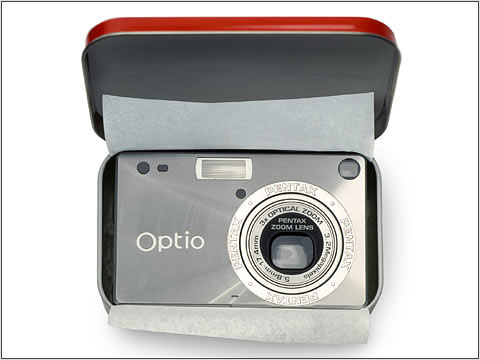

The company has been remarkably consistent over many years. It tends to stick with what works. It tends to come late to the playing field. It tends to make something once and then move on – no "point-two" versions with modified frame counters for this company, no Sir. Perhaps the biggest, most traumatic change of course it ever took was when it decided to miniaturize its offerings in the 1970s with the introduction of the M-series cameras and lenses. Olympus had made a stir with the then-tiny OM-1 (Olympus tried to name it the "M-1," but Leitz put the kibosh on that), and Pentax had been soldiering along for many years making conservative, full-sized, brick-solid cameras like the legendary Spotmatic and the K2-KM-KX workhorses. But once it decided on small, itstuckwith small…decade after decade and down to the present day. The professional LX was small compared to its competition; the ME was nearly dwarfed by its own normal prime lenses; and the recent Optio-S, half digicam and half jewel, famously fit into an Altoids tin.

Most of all, Pentax has consistently been reticent. It just never blows its own horn. (Some of those old photo-dogs like that about it). For instance, some of its lenses are equal in quality to lenses from famous names such as Zeiss, but you’d never hear that from Pentax. Some of its lenses have aspherical elements – but you won’t see that word or any of its abbreviations on the lenses or anywhere in the Pentax literature. Ditto for extra-low-dispersion glass elements. Pentax hasalwayshad more backwards compatibility in its lenses and lensmounts than Nikon, but Nikon gets all the credit there. And speaking of Nikon, remember in the ’90s when Nikon made a big deal of converting all of its AF-Nikkors to "D" status, meaning that they were chipped to convey distance information to the camera’s CPU? Well, lots of Pentax’s FA lenses have the same capability – but they never made a point of telling anyone, either before or even after Nikon’s well-publicized makeover.

Pentax has also traditionally been somewhat, er, quirky in its marketing efforts, too. Well, actually, even in its product planning. Not just inconsistent. Not necessarily incompetent. It just seems to be perennially content to field a motley of products and then let them wend their own way in the world. A few years ago, for instance, the company started issuing a set of premium, metal-bodied autofocus lenses with focal lengths chosen according to some sort of arcane numerology – a 43mm, a 77mm, a 31mm. (The odd focal lengths were not a first for Pentax either: in the early days of the K bayonet mount, it produced a 30mm lens. And I shall forever regret that its proposed "adjustable 35mm" – a 32-to-39mm (!) zoom – never made it to market. I just love the way those people think.) To get back to the story, the metal AF lenses were called "Limited" – despite which, they weren’t limited. And naturally, since they were silver, Pentax aficionados expected that a premium, chrome-bodied AF camera was in the pipeline. Nope. To this day, there is no camera from Pentax that matches the "Limited" lenses visually or conceptually.

That’s Pentax.

So. Come the digital revolution. Following its star, Pentax announces a highly specified, pro-level DSLR, then lets years lapse past with no camera materializing. Sometime during this disappointment, the company grumpily announced that it would forego this newfangled digital nonsense and stick with film products. That must have been right before it became apparent that the whole world was joining the digital parade. A year goes by, and the announcement comes that it intends to be a major player in the digital marketplace. Ooookay. That’s Pentax again.

Finally, out comes the first Pentax digital SLR. Does it have a nice, plain name? Noooo – it’s to be called the *ist. Star-ist? Asterisk-ist? Nobody knows how to say it. It stands for "———–ist," you fill in the blank – preferably with something positive, not "masoch-" or "commun-" or "Stark-" (sorry, Charlie.) Just don’t try to search for it on the web. Then, to add confusion to quirkiness, the companyalsonames afilmcamera the *ist. Thanks for that.

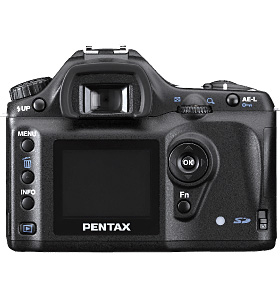

Next, as we know, Canon stuns the world with its keenly-priced "digital Rebel," which it sells by the boatload. Nikon follows with the D70, a better camera if not quite so keenly priced. And then comes the Pentax version – the *ist DS, still bearing the burden of its sibling’s less-than-ideal name. And you know what? It, too, is typical Pentax. It’s johnny-come-lately, it’s conservative, it’s tiny. It’s accompanied by no great buzz and trumpeted by no massive advertising campaign.And it’s one great little camera. Because making great cameras, too, is typical for Pentax, which has made a lot of great ones over the years.

________________________________________________________

Everybody’s got an angle

DSLRs have been around for long enough now that virtually every company is successfully distinguishing itself from all the others with some sort of unique feature. Olympus, by far the most far-out, has its "new standard" 4/3rds system, its exclusively-for-digital cameras and lenses, and its ultrasonic sensor-shaker that does away with dust. Minolta, with its anti-shake built into the body, bids fair to become the low-light champion for anyone wanting lenses not made in VR and IS iterations by Nikon and Canon. Canon has the best full-frame DSLR and its CMOS sensors. Fuji has its own special in-house sensors, most recently the extended-range sensor in the S3. Nikon owns the model with the most bang for the buck.

So what does the Pentax DS offer to make it special? What unique feature sets it apart? Nothing! That’s right, nothing.

Well, actually I suppose you could say small size, which as I say is a longtime hallmark of Pentax products. The *ist DS is the smallest, lightest digital SLR so far. But beyond that, there’s no special feature to grab the fickle attention of the buying public. It hasn’t got anti-shake. No sensor-cleaner. The Canon 20D has better image quality, if only marginally. Several cameras focus somewhat faster. You can get slightly better value out of a couple of others. The DS is not the quietest, the fanciest, the most feature-laden, the most special in any way. Except one.

The DS, you see, has something that a lot of other cameras don’t – and it’s something I personally like a lot. It’s just about "perfectly sorted," to use the term Phil Askey applied to the D2h. It’s plain, which is perfect. While it may not do any one thing the absolute best, it does everything well, in a simple, straightforward, ergonomically sound, and conservatively designed package. It’s small. It’s light. It’s black. It will use almost every Pentax lens ever made, all the way back to M42 screwmount Spotmatic lenses (I love the way these people think. Did I say that already?). By scooping out the inside of the *ist D handgrip, Pentax made room for long fingers, so it fits the hand. The viewfinder is bigger and clearer than the Digital Rebel’s, and has a broader range of diopter correction than the D70 does. Sure, it’s still a reduced-size DSLR viewfinder, which no one has learned how to do correctly yet, but it’s good enough. While not the quietest DSLR around, it’s quiet enough. While not the fastest-focusing, it’s fast enough. And while not thene plus ultrain terms of image quality and high ISO performance for sensors in its size range, it’s darn close – which means it’s very, very good.

Searching for an accurate analogy to sum up my feelings about the DS, I lit upon – what else? – Pentax’s own K-1000. For many years, the K-1000, while nothing terribly special in any particular way, probably came closest to embodying the archetype of the classic SLR. Introduced in the bicentennial year of 1976 as a temporary stop-gap (!) between the K-series bodies and the new, miniaturized M-series, the K-1000 was quickly adopted as the perfect entry-level camera. It was recommended by photography instructors, bought by photography students, packed in backpacks, used as a backup. It just kept selling and selling. It was plain, utilitarian, workmanlike, and very conservative. And people liked it. A lot. According to Herbert Keppler, Pentax kept trying to discontinue it but the public wouldn’t allow it. Originally intended to be in production for no more than two years, the market finally let go of it in 1997, after 21 years in continuous production.

The *ist DS won’t last nearly as long, no doubt. The pace of technological change in digital cameras is just too rapid. But the DS has that same sort of feeling to me that I think older photo-dogs got from the K-1000. It does what it’s supposed to; it does it straightforwardly; and everything’s so well balanced, fitted, and sorted that it just seems, well, right. Classic and conservative. A tool, not a toy.

I’ll have some more concrete "User Report" comments about the DS in a future column. I’ll say more about its technical capabilities and dissect its image quality. You know, all the usual happy-snapper pixel-peeper stuff. But in the meantime, don’t overlook the DSLR that has nothing special – because, in the same strange, satisfying way the K-1000 once did, the DS also has got it all.

— Mike Johnston

See Mike Johnston’s website atwww.37thframe.com.

Also, check out his monthly column in the BritishBlack & White Photographymagazine!

(Usually available at Barnes & Noble bookstores.)

Want to read more? Go to the SMP Archives

Mike Johnstonwrites and publishes an independent quarterly ink-on-paper magazine calledThe 37th Framefor people who are really "into" photography. His book,The Empirical Photographer, has just been published.

You can read more about Mike and findadditional articlesthat he has written for this site, as well as aSunday Morning Index.

You May Also Enjoy...

Turning Photographs Into Art Part 3: Underexposure and Low-Key Images

FacebookTweet Black is the queen of all colors. Henri Matisse 1 – Dusk in the Chinle Buttes There is no road there. The only sign