Yolanda del Amo's decade-long project uses staged large-format photography to explore the emotional distance between people who share the same space.

Explore January’s stunning photo submissions from our community!

Why a $10,000 cinema camera matters to the GFX ecosystem - and what it signals for Fujifilm's future

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get interesting news updates from LuLa delivered straight to your inbox.

Join the newsletter

Our latest articles

All articles

Subscribers Only

Camera & Technology

Photographer Profiles

Techniques

Landscape & Environment

Your most powerful photography tool is the 200 million nerve fibers connecting both halves of your brain.

Hoping someone discovers your work isn't a plan - here's how to actually find the audience your photography deserves.

Notable releases in photography in 2025 and where we are headed.

Next month, 25,000 photography enthusiasts will descend on Zurich for PhotoSCHWEIZ 2026 - here's why this prestigious Swiss exhibition deserves a spot on your calendar.

An end-of-year reflection on why the best camera for a young photographer might not be the "best" camera at all.

Yolanda del Amo's decade-long project uses staged large-format photography to explore the emotional distance between people who share the same space.

Explore January’s stunning photo submissions from our community!

Your most powerful photography tool is the 200 million nerve fibers connecting both halves of your brain.

Hoping someone discovers your work isn't a plan - here's how to actually find the audience your photography deserves.

Notable releases in photography in 2025 and where we are headed.

Why a $10,000 cinema camera matters to the GFX ecosystem - and what it signals for Fujifilm's future

Notable releases in photography in 2025 and where we are headed.

An end-of-year reflection on why the best camera for a young photographer might not be the "best" camera at all.

How ImagePrint Black and Red manage colour and profiling for reliable photo printing.

What happens when the world's dominant drone manufacturer gets caught in the crossfire of geopolitics? We're about to find out.

Yolanda del Amo's decade-long project uses staged large-format photography to explore the emotional distance between people who share the same space.

A Conversation with Prashant Gharpure on Intentional Camera Movement in the Smoky Mountains

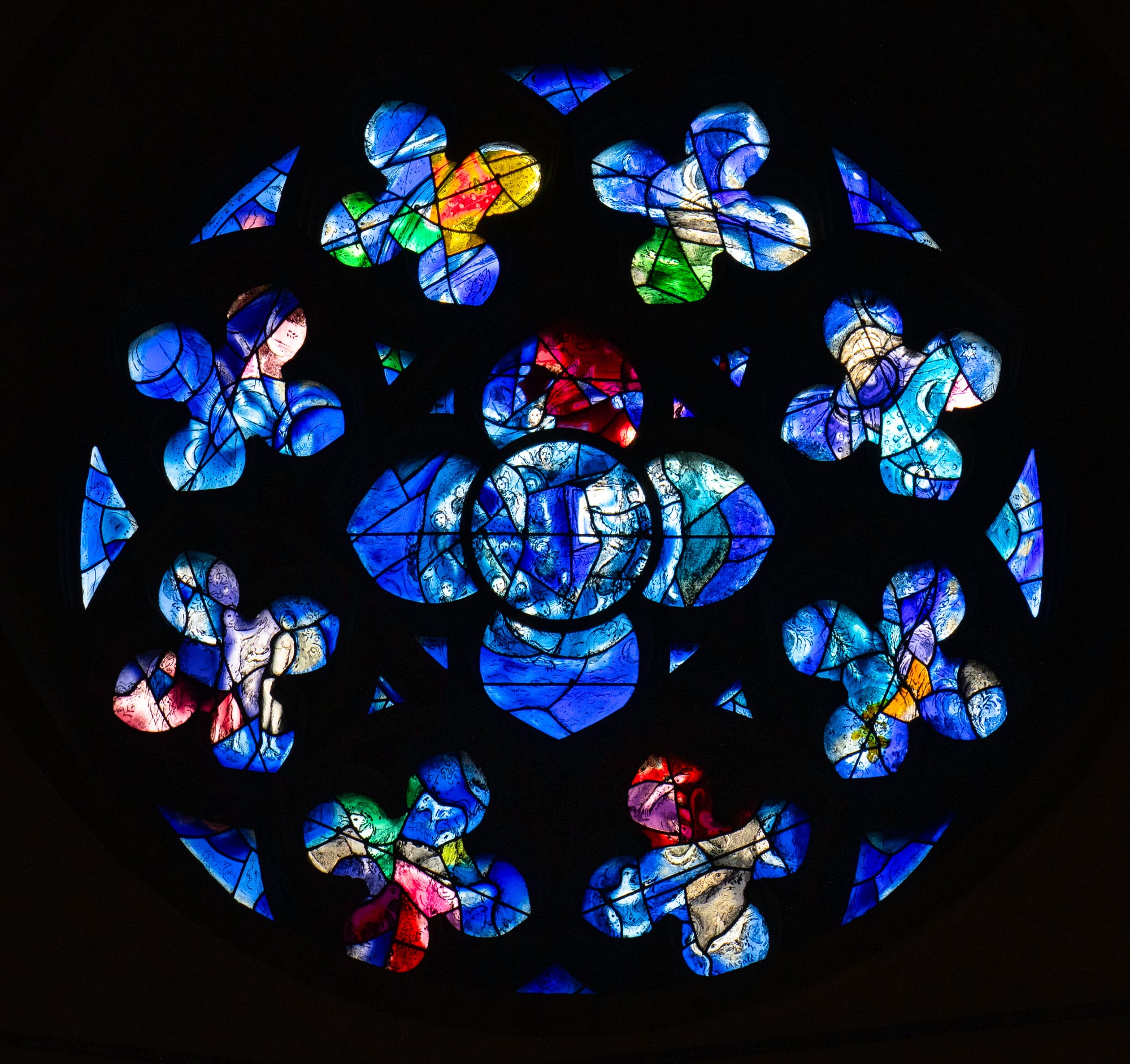

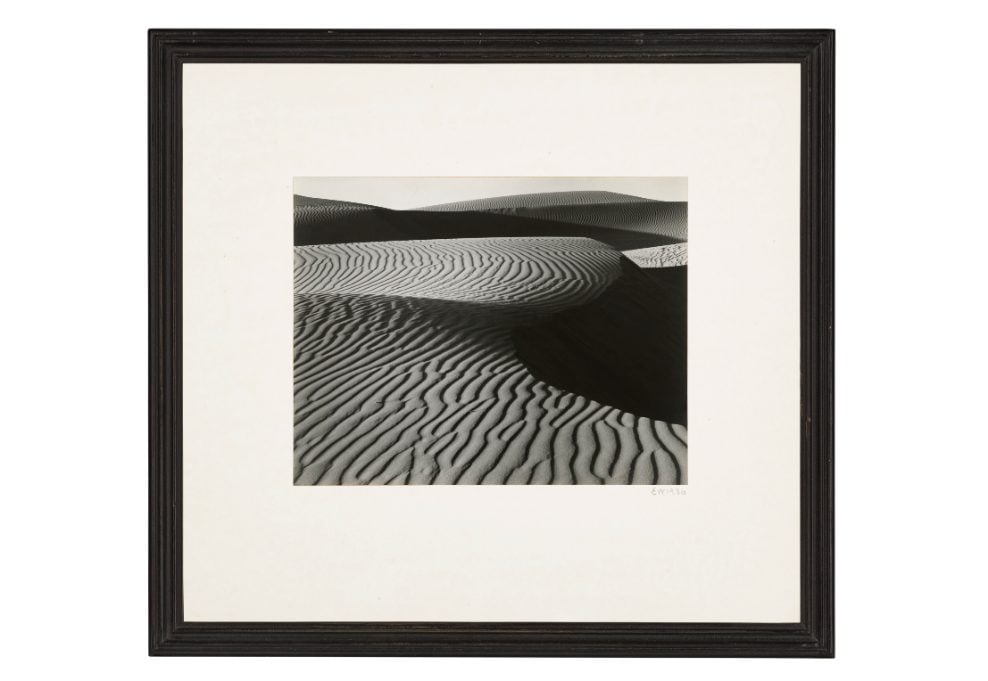

This Christie's sale brings together the titans who invented modern landscape photography, from Adams' technical precision to Sugimoto's philosophical vision.

Why I print every travel story instead of leaving it on a hard drive.

Learn how to eliminate color banding and create silky-smooth sky gradients in your blue hour photography with proven capture and post-processing techniques.

Your most powerful photography tool is the 200 million nerve fibers connecting both halves of your brain.

Hoping someone discovers your work isn't a plan - here's how to actually find the audience your photography deserves.

Master photographic style to create cohesive, professional bodies of work.

A Conversation with Prashant Gharpure on Intentional Camera Movement in the Smoky Mountains

There are no mistakes in art, only attempts - and why that changes everything about how you create.

Your most powerful photography tool is the 200 million nerve fibers connecting both halves of your brain.

Next month, 25,000 photography enthusiasts will descend on Zurich for PhotoSCHWEIZ 2026 - here's why this prestigious Swiss exhibition deserves a spot on your calendar.

This Christie's sale brings together the titans who invented modern landscape photography, from Adams' technical precision to Sugimoto's philosophical vision.

As I wrote the reviews of the GFX 100SII and the 500mm f5.6, I realized that I’ve now used enough of the GFX lens line...

Seeing Carolina and choosing what to photograph.

The most viewed articles

Join for just $2 per month

Join for access to over 5000 in depth articles, hundreds of hours of video tutorials and access to the largest Photography forum.

Be in the Know: Get the Exclusive LuLa Newsletter Sent to Your Inbox!

Get access to exclusive articles, behind-the-scenes content, and become a valued member of our photography team! Subscribe now to elevate your photography experience.

Subscribe Now to Join Us!

Only $2 per month